In the latter half of the twentieth century, artists around the world began incorporating advancements in technology into their work with an eye at addressing widespread civil unrest and encroaching neoliberalism. Glaringly absent in institutional retrospectives of this era are the unique contributions of Latin American artists to these movements. Fortunately, the ambitious Southern California-wide exhibition series Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA introduces the work of these artists to the American public, many for the first time. And while the series covers everything from Pre-Columbian luxury objects to contemporary mural-making, it places particular emphasis on how Latin American artists active from the 1960s to the 1990s used digital media to deal with hostility towards women’s rights, military repression, increased marginalization, and environmental crises.

Within the series, the exhibition “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicana/o LA” at MOCA Pacific Design Center paid tribute to the work of US-born Pauline Oliveros, who fought for female inclusion in the world of sound art. Oliveros was a pioneer, pivotal not only for her work’s link between sound and the female body, but for the development of experimental music more broadly, helping to establish the Deep Listening Institute and the San Francisco Tape Music Center. In 1964, she completed “Bye Bye Butterfly,” a contorted recording of Puccini’s opera, intended, as Oliveros claimed, to undermine the cultural and artistic forces that contribute to female oppression. During the 1970s, she founded the ♀ Ensemble, a non-hierarchical group of women seeking to harness the social power of sound. The group met at Oliveros’s home in Encinitas, where they practiced “Sonic Meditations,” a method of “tuning mind and body.” According to Oliveros herself, the group was “purposely all female in order to maintain a common, stable vibration within itself and to explore the potentials of concentrated female creative activity, something which has never been fully explored or realized.”

Detail of Life Cycle: Electric Light + Water + Soil —> Flowers —> Bees—>Honey, Juan Downey, 1971. Image courtesy of Pitzer College Galleries, Claremont CA.

The galleries at Pitzer College and LACE presented a monographic exhibition on Chilean-born Juan Downey, whose work was contemporary with some of the first artistic experiments with video feedback systems. The experimental project A Vegetal System of Communications for New York State (1972) reflects Downey’s interest in invisible communication networks and interactive art. The project proposed the use of electromagnetic energy between humans and philodendrons as a navigation tool across forests. Life Cycle: Electric Light + Water + Soil —> Flowers —> Bees—>Honey (1971) is another, which plays back live footage of bees at work atop a live bee colony within the gallery space.

Downey’s comprehensive career also covered extensive research on Latin America politics, Chile in particular. His later work turned to the intersection of ecological concerns and cultural imperialism. In The Laughing Alligator (1979), the artist captured moments among the Yanomami—a group indigenous to the Amazon, coveted by anthropologists for their cultural isolation—that effectively mocked the role of video documentary for anthropological studies. Downey’s practice is perhaps most remarkable for the way in which its confrontational subject matter is tempered by the encouragement of intimacy between the viewer and the work.

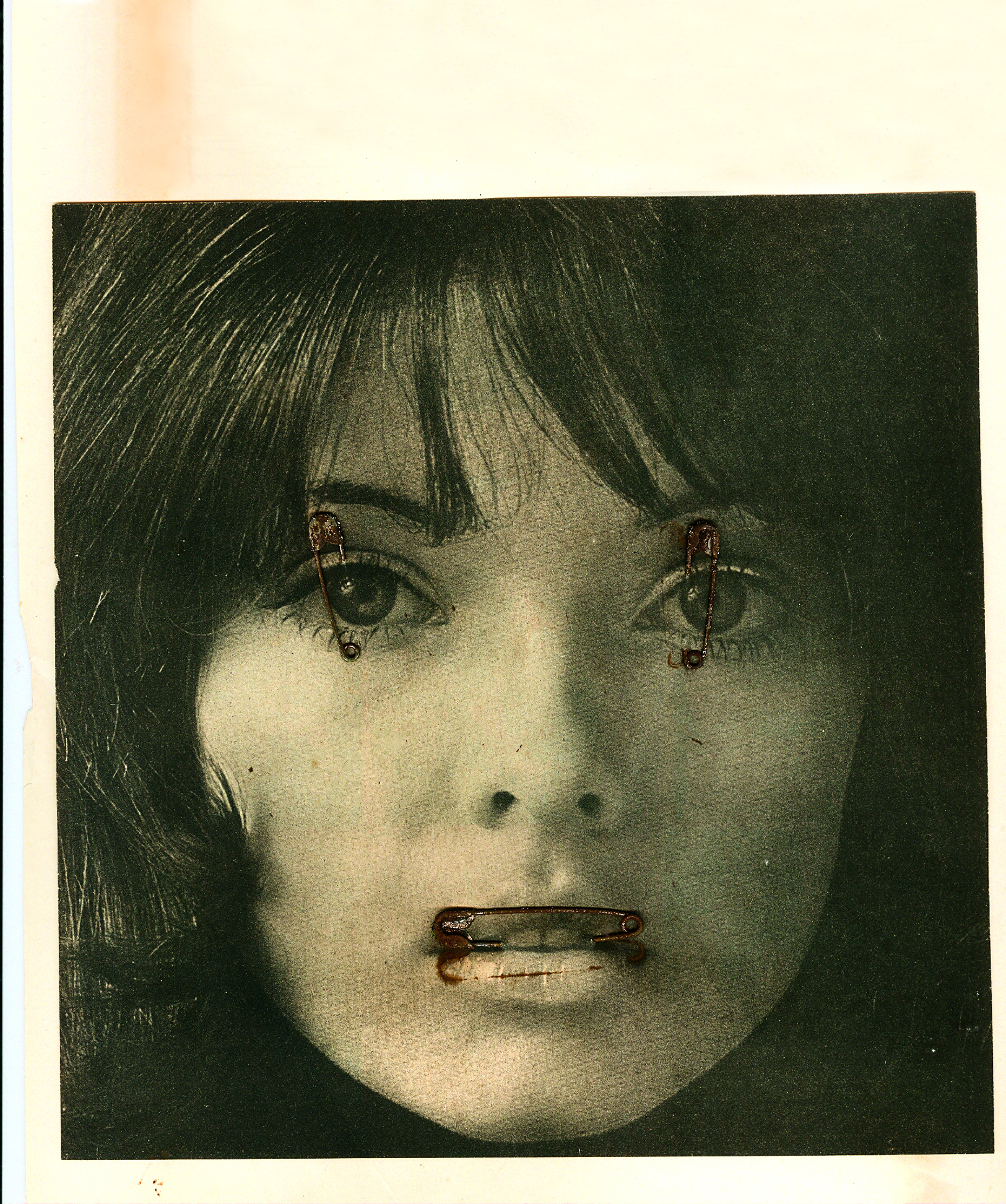

Around the same time in Brazil, a military dictatorship began censoring traditional art practices, pushing artists into uncharted media. “Xerografia: Copyart in Brazil, 1970-1990” at the University of San Diego explored twenty years of Xerox art in Brazil, a movement analogous to the copy art and electrographie movements in the US and France, respectively. Among the constellation of artists that began working with Xerox as a means of subverting the increasing bureaucratization of Brazil, Anna Belle Geiger stands out for her encapsulation of how US and European artists at the time overshadowed their Latin American counterparts. In Diário de um artista brasileiro (1975), Geiger inserted cut-out photos of herself and placed them alongside renowned figures like Duchamp and Lichtenstein, highlighting her double-marginalization as a female Brazilian artist. Geiger’s student Letícia Parente would take up similar practices in works such as Women (1976), in which she uses safety pins to pierce the surface of a photocopied magazine ad portraying a young woman's face in close up. Others like Léon Ferrari, Hudinilson Jr., and Paulo Bruscky toyed with the boundaries of the Xerox medium, challenging conceptions of art as a luxury object, while exploring its potential use as a medium for communication.

Letícia Parente, Women, 1976. Image courtesy of University of San Diego.

All of these artists enact, in their works, a resolute sense of playful instruction that both informs their audience about Latin American issues beyond the gallery space, and further reveals the liberating capacities of new media. What’s more, the PST exhibitions focus on the merits and contributions of these artists as global influencers in their own right. Rather than restrict the works to their relation with more well-known artists working within a similar network, the shows do justice to the regional and identity-based signatures of Latin American artists as they stand on the early landscape of digital art practices.

More PST shows are open throughout this month and well into the spring. These include: “UnDocumenta” at the Oceanside Museum, which explores the use of technology in the work of artists working along the California-Mexico border; “Hope” at ESMoA, which surveys the video work of living Cuban artists, and “Photography in Argentina, 1850–2010: Contradiction and Continuity” at the Getty which showcases the work of avant-garde Argentinian photographers.

Header image: Detail of Life Cycle: Electric Light + Water + Soil —> Flowers —> Bees—>Honey, Juan Downey, 1971. Image courtesy of Pitzer College Galleries, Claremont CA.