This text accompanies the presentation of Art Thoughtz as part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

“On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” goes the famous New Yorker cartoon. The notion that the web might offer a site of radical mutability for the formation of new identities, unhindered for the first time by the constraints of “meatspace” seems to have been primarily, although unevenly, dispelled by way of the quotidian creep of the private sector’s stranglehold on the public sphere. In contrast, the shift from an understanding of the web as predominantly characterized by “immateriality” to one that recognized its reliance on material infrastructures—undersea cables, electromechanical generators, low-wage content moderators—required an intervention on the level of discourse. Perhaps the question of online identity is felt more strongly. One thinks of the viral photo of Zuckerberg walking confidently through a packed press conference, as if it were his birthday, surrounded on all sides by an anonymous sea of eager attendees donning his company’s VR headsets; Zuck has the viscerally world-historical power to make his fantasies our reality.

The ubiquity of Web 2.0 has changed the way that we see ourselves, offering indispensable means for individuals to feel themselves out, learn about who they are or want to be, and find communities of like-minded users. And yet, the sense that the web demarcated a liberatory elsewhere pervaded by a democratic ethos has diminished greatly in recent years, precipitated by the re-recognition of the material grip of social forces that have long predated social media. A decent amount of net discourse was centered around this since-eroded premise, and as a result ended up engaging with what turned out to be oftentimes illusory notions of networked identity as malleable in a historically novel way. Despite the fact that it was made in what was for many a very futuristic-feeling moment, New York-via-Philadelphia artist Jayson’s Musson’s Art Thoughtz (2010-2012) project is remarkable for how much it sticks with the slow grind of history. The work is a vlog series that comedically explains contemporary art concepts ranging from beauty to “How to Make an Art” through the character of Hennessy Youngman, and its virality significantly helped put Musson on the map as a contemporary artist. It remains powerful due in equal measure to its hilarity, historicity, and almost uncanny prescience of certain tenets of contemporary meme humor.

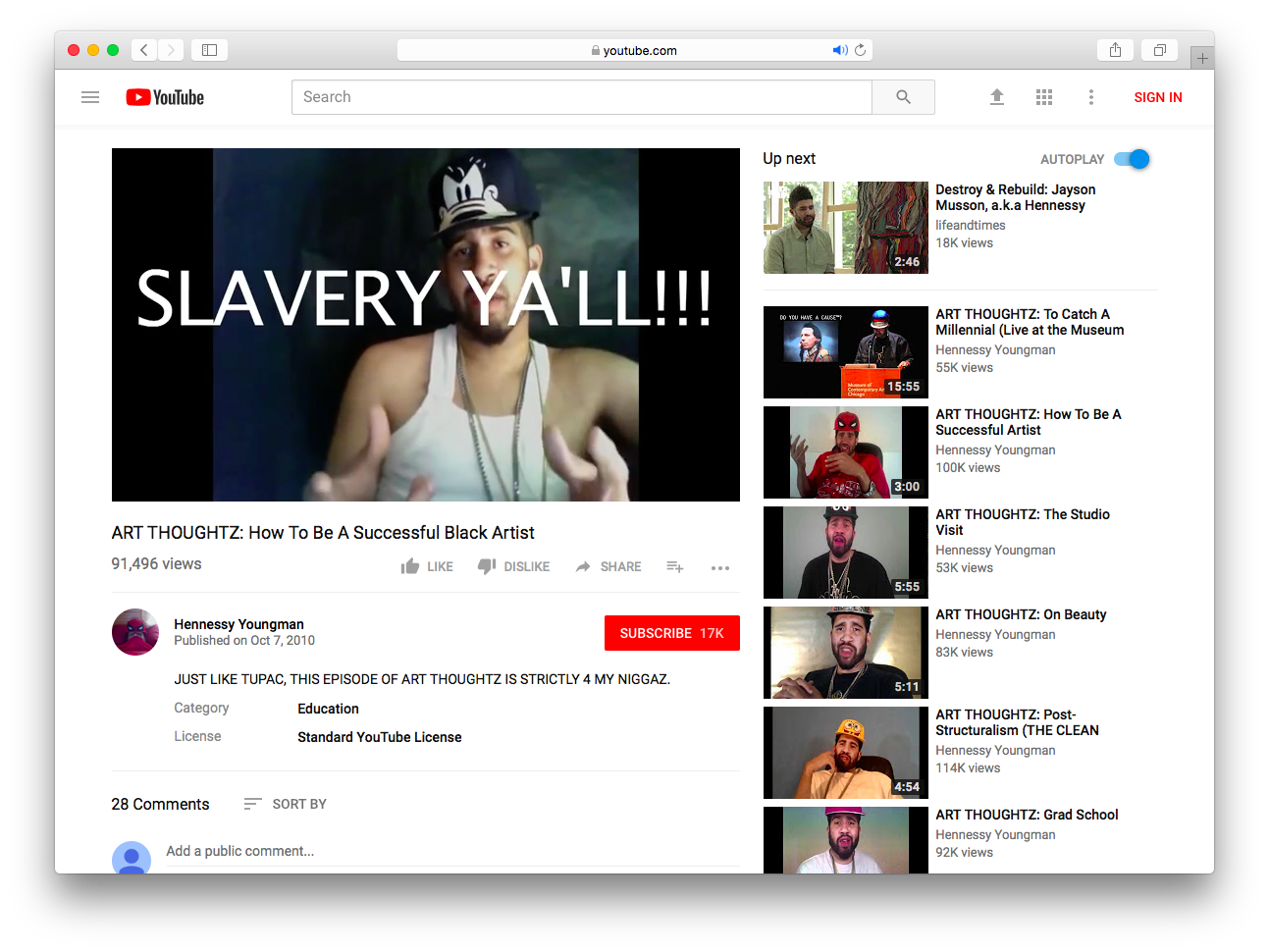

Much net-engaged artwork—from Ryan Trecartin to DIS Magazine’s visual practice—has been heavily engaged with the new as a foremost point of departure, often for understandable reasons: new ways of seeing, new modes of governing, and new ways of relating to one another are all conditions that ask to be explored. Fetishization of “the future” as a reified concept has underpinned many of these investigations, and proved to be indispensable to their commercial potential in the contemporary art market. Interestingly, Musson’s Hennessy Youngman character invokes the future much less often than his peers. A memorable time that he does, though, is in the 2010 clip “How To Be A Successful Black Artist,” when he encourages fellow Black artists to use “brainy” terms like “post-Black” in order to secure legitimacy in the art world. “Honestly I don’t know what the fuck [post-Black] means,” he says, “‘cause it means ‘after black,’ and n*ggas is still n*ggas … Is it like, did someone from the future come back with that term and n*ggas is like, pink in the future?” In a moment of brilliant denouement, Musson cuts to David Hammons’s 1988 painting How Ya Like Me Now, featuring a white Jesse Jackson.

It is not an accident that Musson-via-Youngman’s commentary on one time-buzzword themes like “circulation,” “dissemination,” and “networks” doesn’t sound dated several years later, despite the fact that most commentators completely ignored it as such at the time. Throughout Art Thoughtz, Musson actively recognizes and comments on the vulnerabilities built into the circulation of his own Black image in an anti-Black art world—based upon a libidinal economy that takes pleasure in his suffering, following Frank Wilderson III—and anticipates them, teases them, and deflects them. The series as a whole anticipates what Aria Dean would later theorize as the blackness of memes: “Memes move like blackness itself, and the meme’s tactical similarity to historical black cultural forms makes them — predictably — vulnerable to appropriation and capture. The meme is a form that allows for a sense of collective ownership among those who come into contact with it — black or nonblack.” Is it really possible to talk about circulation in the context of global capitalism without invoking the transatlantic slave trade, the history of colonialism? To the white viewer blackness is always already property, first and foremost; Musson reminds us that “circulation” has a history. For some, meatspace is not flexible, particularly when we consider this term’s resonance with Hortense Spillers’s concept of the flesh as the “degree-zero of social conceptualization,” where the distinction between “body” and “flesh” demarcates the difference between captive and liberated subject positions.

In a particularly memorable passage of Claudia Rankine’s 2014 book Citizen, the Jamaican-born American poet discusses Youngman’s discussion of the marketability of Black anger in Art Thoughtz alongside Serena Williams career-long battle against pervasive racism in tennis, a field that like fine art is notable for its overwhelming whiteness. Rankine writes that Musson’s work prompts the recognition that “no amount of visibility will alter the ways in which one is perceived.” With this in mind, Youngman’s suggestion that artists embrace ambiguity in another, earlier video, entitled “How To Be A Successful Artist,” takes on new resonance. He makes the recommendation after advising that the artist 1) be white, or 2) be a white man, or 3) be a white woman. Perhaps his proposal, as the flip side of its parodic intent, suggests a certain a strategy of refusal—enacted via something like hypertextual, non-verbalized memetic dissemination—as much as it is wry parody of the seemingly limitless supply of rote gallery press texts quoting continental philosophers for no apparent reason. “The less mothafuckas’ is able to understand the artwork,” he says, “the more they can put into it.”

For all of Art Thoughtz’s incisive commentary, though, it is important to remember that the project is a fundamentally comedic series that initially took the form of a (staged) live stand-up set. Although Musson quickly abandoned the stand-up format, he retained the direct address to an audience and unpredictability typical of live comedy. It is nothing like a manifesto, and its ideological alignment is hard to pin down or tie to a certain political position in any conclusive, thorough sense. Unlike the strands of humorless, MFA-core artistic production that Youngman offhandedly skewers, the mode of address in these vlogs is captivating for its fundamentally unpredictable approach to performance and the consolidation of meaning. Comedy undergirds all of Musson’s work, from social media to the white cube, and he excels in bringing out the genre’s “epistemologically troubling” characteristics, in the words of Lauren Berlant and Sianne Ngai. Humor has a unique ability to render perceived distinctions and modes of typology fuzzy and unstable, ungrounding assumptions and subverting everyday behavioral codes. Art Thoughtz is so effective in part because Musson’s virtuosic control over this mode of playful cognitive incursion is simultaneously devastating and blasé, genuinely conveying the sense that he would make the videos when he felt bored. His video on institutional critique opens with the Diplomats’ NYC rap classic “I Really Mean It” and features the line, “Auschwitz was and still is the premiere institution of the 20th century, making the MoMA look like nothin’ more than an over-glorified collection of thrift store paintings.” What are we supposed to even do with this information?

Each successive era of popular online culture has had its quintessential meme style, and it is remarkable to consider how much Art Thoughtz presaged forms and styles of the mid-2010s. From the style of plain-spoken, at times risqué gallows humor he perfected to the ways in which the project was designed for widespread informal dissemination—sidestepping institutional gatekeeping in the process—the work is almost uncanny in its prescience of the current moment. Additionally, it engaged the affective dimension of what Hito Steyerl has called “poor images” while anticipating the contemporary omnipresence of what manuel arturo abreu has called Online Imagined Black English, or digital blackface. The degree to which this phenomenon is absolutely essential to the online economy of intertwined cultural capital and moral capital—all across the political spectrum, notably—is perhaps best summed up by a post by meme maker Cory in the Abyss which declares, in a riff on high-budget Hollywood movie posters, “You wouldn’t last a week without digital blackface.” As abreu states in an interview with another meme producer, Gangster Popeye, “Lots of people think weird Facebook [and its associated meme culture] popped up out of nowhere, but in reality a lot of non-black meme production draws from black language, visual style, and meme content.” Musson doesn’t “predict” this contemporary confluence of forms so much as he seems to stumble upon it, which makes the historical linkage all the more striking. In another prescient move, Art Thoughtz manages to anticipate the popular pedagogical function of memes-as-poor images, where intellectual concepts designed to dismantle dominant power structures are deftly employed clearly and cuttingly, without the baggage of institutional ostentatiousness.

For many commentators, what Art Thoughtz had to say was illegible either because it was too much to bear or because they were limited by a preconceived idea of what they were watching. In two separate pieces of press published around Art Thoughtz’s initial release Musson/Youngman is compared to Ali G according to some kind of alchemical pretzel logic, while one particularly overt piece calls the character an “idiot” and a “moron,” citing his “over-the-top thug speak.” It is an understatement to say that Musson/Youngman’s analyses of mainstream contemporary art’s pre-packaged script for success wasn’t taken seriously by most commentators. A revealing aspect of this coverage is the slippage it figured between Youngman as an avatar of excessive blackness—both a voyeuristic object of desire and revulsion, love and hate—and Musson the person. In terms of Art Thoughtz’s palatability in terms of respectability and assimilability, the blackness portrayed in the videos seems to simultaneously be deemed too much and yet not enough; Tavia Nyong’o has written about the ways in which Dread Scott and Coco Fusco “employ masquerade to reveal potent anxieties about displays of excessive blackness, excesses that are almost always read through gendered expectations of appropriate behavior.” This recurring theme raises a question: would Musson have been able to circulate his work and get gallery representation in the New York art world if he didn’t take on the Youngman character?

By virtue of cunning in combination with being in the right place at the right time, he succeeded in hacking the cybernetic feedback loop of value accretion in the culture industry on the protocological level, subversively appropriating the then-emergent tactics of the “power user” while highlighting the inbuilt limitations of the system he gamed. As it gained traction online, the work demonstrated a keen understanding of the way viewership accumulates and multiplies itself on networked social media platforms according to what content is most likely to be shared. In other words, Musson anticipates and plays with the way his work will be aggregated—filtered for consumption through search algorithms and screen-based interfaces—both in and outside of the art world, while highlighting the ways in which information capitalism’s mass systems of circulation are inherently anti-Black. “[Art Thoughtz uses] a different form of dissemination than we’re used to in the gallery system,” said the gallery owner of Salon 94 at the time of its presentation of his first New York solo show, “Halcyon Days,” in 2012. “He’s probably the first artist who has been able to bridge that online audience and the art audience as well, so that’s always been interesting to me, how to break through audiences and cross audiences.”

Musson’s hilariously sharp Art Thoughtz video about relational aesthetics is striking to consider in connection with the fact that in 2012 he was invited to do a project at relational aesthetics-affiliated artist Maurizio Cattelan and curator Massimiliano Gioni’s Family Business exhibition space in NYC. For “Itsa Small, Small World” he created a call for entries video as Hennessy Youngman, inviting anyone and everyone to drop off work to be included in the show during a three-day window, with no one turned away. The project sounds curiously like a riff on relational aesthetics themes in retrospect, as it brought together an assortment of people from all walks of life in a block party of sorts on the hallowed grounds of Chelsea, facilitating a highly unusual and defamiliarized mode of social relation in the process. Musson later wrote that the exhibition was partially “born out of a curiosity to see what the audience for my Hennessy Youngman videos looked like, to basically see what the internet could look like in physical manifestation.” Later, in 2015, he received a double platinum plaque for having his voice sampled on the drop of electronic producer Baauer’s “trap” single “Harlem Shake,” released on a sub-label of Diplo’s Mad Decent imprint in 2012. Although Musson was originally sampled on the song without his knowledge or permission—the recording came from his since-disbanded rap group Plastic Little’s 2001 song “Miller Time”—he described compensation negotiations with the label as friendly in an interview with the New York Times, conducted after Baauer’s track topped the Billboard Hot 100 chart. To many, the song and the viral dance video craze it spurred constituted a straightforward form of semiotic gentrification in its essential disavowal of the original Harlem shake dance created in 1980s New York City. Here, Youngman’s elucidation in “How To Be A Successful Black Artist” of the market logic of the “jazz principle”—whiteness’ insatiable desire for the exotic other—comes to mind.

It is worth situating Musson’s work in relation to the history of Black performance art engaged with themes of humor and stereotype. Relevant works include David Hammons’s 1981 performance Pissed Off, in which he photographed himself urinating on a Richard Serra sculpture named after the Transport Workers Union, only to be accosted by police moments later. Another is William Pope.L’s The Great White Way (2001-2009), which saw him crawl across 22 miles of Broadway in Manhattan in a Superman outfit, channeling unbearable trauma like an abject jester, while a third is Adrian Piper’s 1983 video Funk Lessons, where she teaches her non-Black audience about funk and how to dance to it. In contrast with these disparate works, which all stage iterations of encounter and symbolic exchange in various concrete ways, Art Thoughtz remains striking for how off-the-cuff it feels, as if it weren’t even invested in itself; improvised cunning, as opposed to extensive premeditation, comes to mind again as an apt descriptor. The project’s lack of self-seriousness also contrasts with much contemporary art dealing with “identity,” which often shares a grave, scholarly, and sincere vernacular with activism and academic thought. “Intellectualized or aestheticized trauma is displayed for institutional, artistic, or academic validation, but physical and emotional trauma goes untreated, because it falls outside the bounds of institutional relevance,” writes Hannah Black. While Musson’s underlying messages are indebted to a lineage rooted in high-stakes political resistance, the work comes across as a little bit more ambivalent. We can sense what he thinks and how he feels, for the most part, but he mostly seems to be moving in his own singular orbit, outside the bounds.

Considering Art Thoughtz in its original context, it is helpful to revisit Seth Price’s highly influential 2002 essay “Dispersion,” where the New York-based artist argues that artists should embrace mass media in order to pursue a “categorically ambiguous art, one in which the synthesis of multiple circuits of reading carries an emancipatory potential.” In her introduction to Rhizome’s group exhibition “New Black Portraitures,” Dean notes that the most abundant images of Black people are of “memes, celebrity content, and images of protest and state-sanctioned violence.” We are left wondering if mass networks ever truly had anything like “emancipatory potential.” Might that just be hardcore romanticism? Cue Youngman’s video on the sublime, searching but unable to find it in the forest, shooting a gun into the sky. In a way the clip is shockingly beautiful in its low-res haze, a banal irruption of the real that requires no drastic mode of seeing.