Do you remember when people misheard the words “fuck that” on the chorus of Kendrick Lamar’s “A.D.H.D.” as “fuck thought?” Well, fuck thought. Kind of. Let’s talk about it.

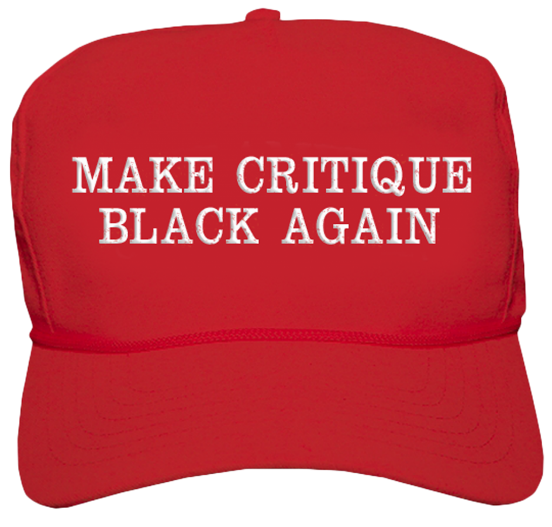

- REANALYZING THE THOUGHT FETISH

By means of “lack of reason”—with religion, language, appearance, and other aspects serving as a litmus—the animalization of Black and brown people has been a critical tool of domination, invented to justify the white conquest, genocide, slavery, and other violence that engendered the contemporary.

What does it mean, then, that art today prizes thinking and the aesthetics of thought such as criticality, divestment from the sensory, and a demeanor of philosophical objectivity? The white West used these very criteria to dehumanize the global south and facilitate Euro expansion; in a specifically aesthetic context, modernism itself was premised on the spoils of imperial conquest.

Despite clarion calls of posthumanism, it is possible to excavate an exclusionary humanism in the fetishism for “objective philosophical thought” in contemporary art which preserves the modernist dynamic of treating Black and brown people and aesthetics as raw material. We can recalibrate our definitions of art from the contemplation and production of the beautifully useless and self-referential. A continued utilitarian project of the violent subsumption of non-white aesthetics is possible through reading Allan Kaprow’s concept of post-art in the context of the Middle Passage and its afterlife.

- THE CONTEMPORARY

David Joselit defines the contemporary as a mode of aesthetic governance relegating marginal practitioners into a position of debt to modernism. For Joselit, this imposition of debt mirrors governance by debt in neocolonialism, rendering what he calls heritage or local context merely a dividend of debt, serving to diversify the art market and globalize its structural tropes (such as painterly abstraction, the white cube, the biennial, etc).1

Joselit’s analytic is useful for unearthing not only the originary violence of modernism with respect to Black and brown aesthetics, but also the ways the contemporary continues this project of subsumption.2 Aesthetic governance by debt allows the increasingly marketized art world to commoditize difference and deploy it for its own ends, whether financial, nationalist, or otherwise.

Yoked under modernism, marginal artists must assimilate to standard aesthetics3 and allow themselves to be deployed in service of institutionality. At a deeper level, aesthetic governance by debt allows art to deny modernism’s own constitutive debt to Black and brown aesthetics, which it used as raw material to shirk the constraints of earlier white art such as three-point perspective and objecthood.

The contemporary is an echo of modernism, it continues the edict of modernism while developing new forms of governance over marginalized artists.

- THE END OF ART

In the afterlife of conceptualism, thinking overcame and reframed making, and embodied a Hegelian assumption of teleological human evolution, such that Western society has outgrown the stage at which art is the supreme mode of our knowledge of the Absolute. Hegel says “We have got beyond venerating works of art as divine and worshipping them… Thought and reflection have spread their wings above fine art.”4

During Western industrialization, art’s dependence on the sensory caused it to fall behind thought as the highest vocation and prime engine of knowledge, whose “very essence… is to go from the observable to the non-observable, from the immediate to the mediate.”5 For Hegel, human cultural developments like art and religion are vestigial forms, reflecting an older dependence on the sensory before the modern mastery of nature represented by industry.

For Hegel’s teleology, art is over, but it remains a necessary step in human development: aesthetic contemplation and production indicate the gradient between human and non-human, setting the stage for reason to flourish. It is precisely the intimate revelry of the sensory which, when refined, allows for the philosophical flight into the immaterial, the theoretical, and the nonsensory. Without art, philosophy could not have risen.6

- THE CONCEPTUALIST GAMBIT

By dint of art’s putative necessity to human development, conceptualism attempted to salvage the patrimony of Western art by ushering thought itself into the set of available artistic mediums.

From this lowered position, modernist aesthetics worked to expand the boundaries of what could be institutionalized as art. Conceptualism went further, and deployed the autonomous inutility of the art object inherited from modernism to show how, as Allan Kaprow states, “art has served as an instructional transition to its own elimination by life.”7

While this may have partly emerged from idealistic notions of thought as medium precluding subsumption into the commodity form, the result was that the subject and role of art—which for Kaprow was “the ritual escape of Culture”—simultaneously subsumed and supervened on the sociopolitical, becoming instead a kind of immaterial or diaphanous residue which could coat any imaginable life context. In modernism, the idea that anything could be art was scandalous, whereas in conceptualism, this indeterminacy became mundane.

With art more deeply yoked to culture, art became a toolkit for interacting with the lived conditions of humanity akin to a social science or school of thought. The modernist decline of art’s primacy resulted in the simultaneous expansion of art to whatever; the reduction of art to commentary on world affairs and meta-comments on its own history; and the valorization of thought as the ideal medium for aesthetic practice in this new context.

Kaprow’s concept of post-art exemplifies this, blurring the line between art and life since “nonart is more art than Art art.”8 Whatever a person wants to get out of art, life has more of it, and art’s duty is to take on a managerial relationship to the sensory by existing in a state of fluidity, even precarity—and in this ephemeral state it haunts life, it folds all life into it. With this vastly expanded aesthetic field, thought as artistic medium engenders a process of art mimicking the disciplines of thought—namely science and philosophy.

- AN OAK TREE (1973)

It is instructive to consider a work that exemplifies the conceptualist gambit of folding thought into the set of available artistic mediums, with its resultant valorization of reason and philosophical aesthetics.

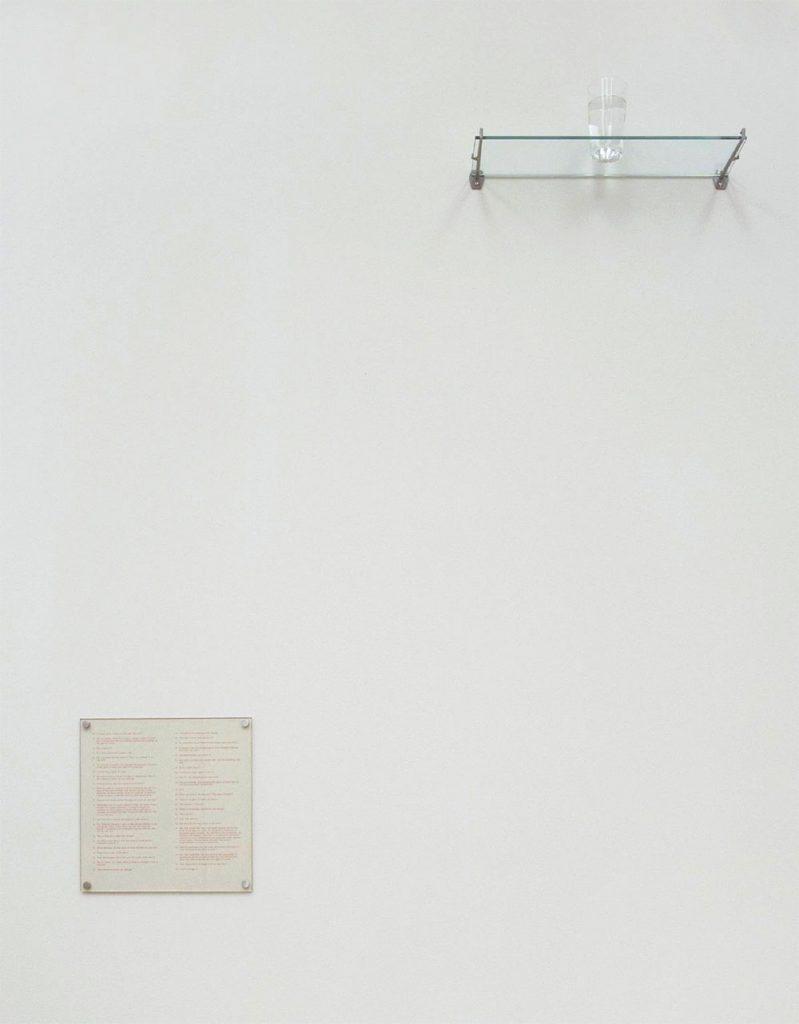

Irish artist Michael Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree (1973) is a conceptual work consisting of a glass of water placed on a glass shelf 253 centimeters off the ground with an accompanying text.9 The work was first shown at the Rowan Gallery in London, 1974. In Q&A format, the text explains the artist’s process of “changing a glass of water into a full-blown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water.” The oak tree resulting from this metaphysical alteration “will not ever have any other form but that of a glass of water,” and when pushed to answer the question of where the art is, Craig-Martin states in the text that this resultant oak tree is the art object.

Image courtesy of Michael Craig-Martin.

An Oak Tree (1973) plays on the Aristotelian supremacy of essence over accident. The essence of the oak tree persists, despite all of the sensory evidence to the contrary. The ostensible transformation is not aesthetically accessible, and therefore the particular oak tree presented to the audience has no aesthetic dimension at all. Rather, the aesthetic dimension is entirely accidental to the essence which is intended for gallery display: the former is a glass of water, the latter is an oak tree.

The work also reflects the artist’s Catholic upbringing, drawing on the concept of transubstantiation. At the last supper, “Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, ‘take and eat; this is my body.’ Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, ‘Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.’”10

At communion, Catholics ceremonially consume a cracker and wine to signify the bread and wine which at the last supper was, in essence, the flesh and blood of Christ—despite the accidents of the bread and wine. With this shade of meaning, the artist intends to “deconstruct the work of art in such a way as to reveal its single basic and essential element, belief that is the confident faith of the artist in his [sic] capacity to speak and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what he [sic] has to say. In other words belief underlies our whole experience of art.”11

An Oak Tree (1973) is a fine example of the conceptualist gambit and its vaunting of thought: it simultaneously extricates itself from the abject sensory, and more deeply yokes itself to it (since after all of this metaphysical transformation from a glass of water into an oak tree, the sensory dimension still indicates only a glass of water). In dissecting the social contract between artist and audience, it speaks to contemporary art as a secularized iteration of an originally theological endeavor, one which served as a litmus for humanity.

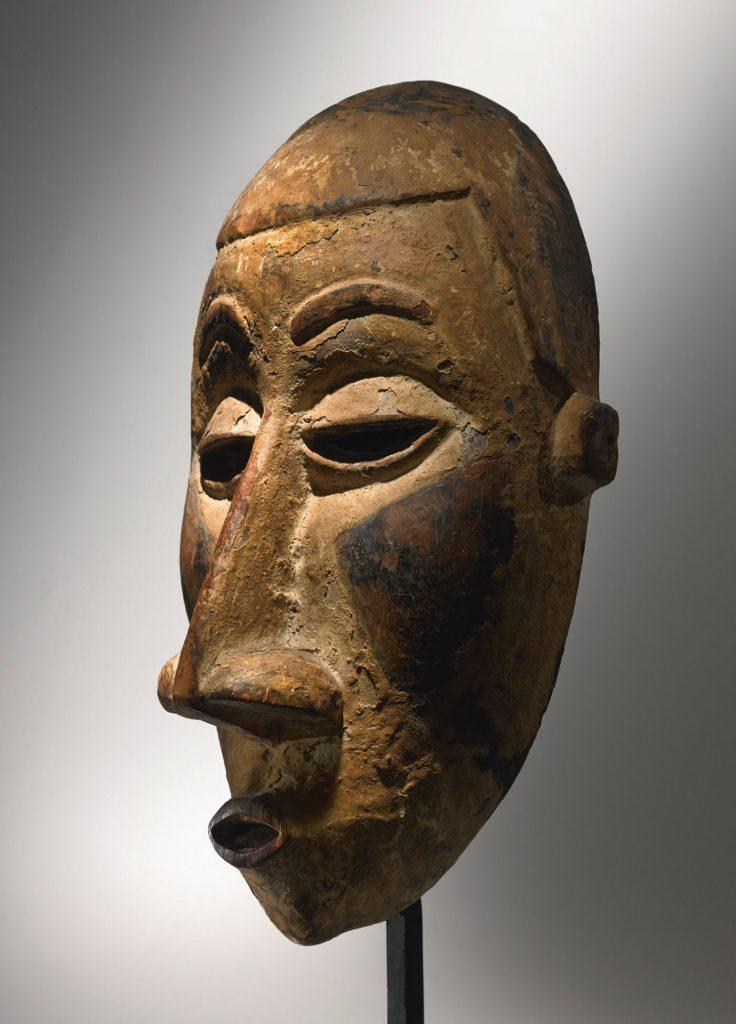

Kongo-Yombe Mask, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

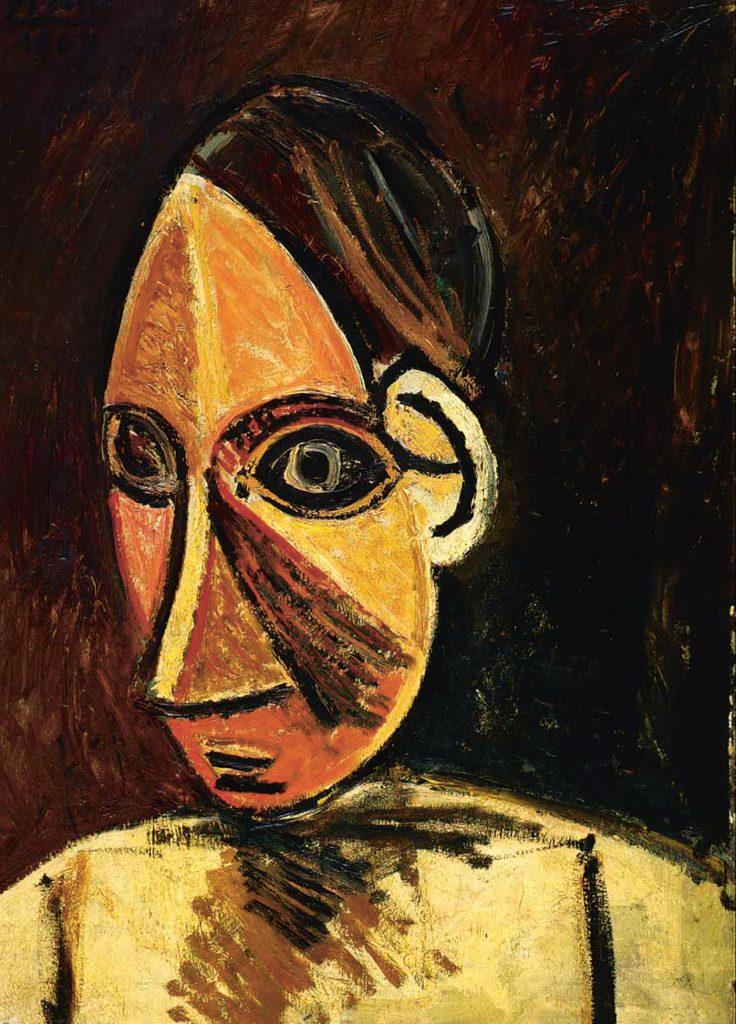

Picasso, Head of a Woman (1907).

- CARTESIAN DUALISM AND ANTIBLACK ANIMALIZATION

The concept and value of thought in the West belie a desire for divestment from the ostensibly inferior world of sensory phenomena in line with Cartesian mind/body dualism, where bodies are organic machines, and only humans, with reason and language, have souls. As Descartes claims, non-human animals, are simply one more facet of nature ripe for use: “they have no mental powers whatsoever… it is nature which acts in them, according to the disposition of their organs; just as we see that a clock consisting only of ropes and springs can count the hours and measure time more accurately than we can in spite of all our wisdom.”12

According to this idea, a body can only supercede the machinic laws of nature with rational thought; all else serves as the sandbox in which to perfect reason, living and breathing but nevertheless objectified. In this way Cartesian dualism demonstrates that “the practical elaboration of making a commitment to humanity is inhumanism… humanism is by definition a project to amplify the space of reason,”13 Humanism’s project to expand the scope and analytic power of reason requires a corollary dehumanized faction to serve as its foil and ground of deployment.

Building on Cartesian dualism, Hegel argues that “in Negro life the characteristic point is the fact that consciousness has not yet attained to the realization of any substantial objective existence, … What we properly understand by Africa, is the Unhistorical, Undeveloped Spirit, still involved in the conditions of mere nature, and which had to be presented here only as on the threshold of the World’s History.”14

Hegel frames his mention of Africa as perfunctory, but his portrayal of Blackness as primordial is a necessary assumption for his teleological understanding of history, which evolves toward European reason. Hegel transfers Descartes’ human/animal dichotomy to the realm of human difference, and positions Africa as an inhuman prehistory without thought in order to naturalize slavery and conquest in the “development” of the West.

- THE VIOLENCE OF MODERNISM

In art we find a similar process. It was through the animalization of Black and brown people as lacking reason that white artists could render non-white lands, aesthetics, and bodies as raw material to modify and deploy in response to Western art history, both conceptually and materially. By confining Black bodies to what Orlando Patterson terms “social and ontological death”, the West could render us simultaneously as the fungible cornerstones of its program, and as valueless vestiges of prehistory.15 As Murrell states, the stolen objects that served as the inspiration for modernism “were treated as artifacts of colonized cultures rather than as artworks, and held so little economic value that they were displayed in pawnshop windows and flea markets.”16

Armed with the fruits of conquest, white art ‘developed’ away from representation (and eventually objecthood entirely) by means of positing the supremacy of thought as surfing on colonial spoils. Picasso, for example, said “African sculptures had helped him to understand his purpose as a painter, which was not to entertain with decorative images, but to mediate between perceived reality and the creativity of the human mind.”17 The same tendency continues today, with Black and brown life “inspiring” white art, with non-white artists strategically included to absolve the white cube and diversify the market.

In response to the squalor of phenomena, art turned the lived into solely a surface for thought: thinking itself is the best medium for art when the entire universe is accessible as source material, allowing a performative divestment from modernist values while simultaneously arguing for the value-neutral availability of its tools in a newly managerial aesthetic practice.

The vaunting of thought in the contemporary in which criticality is a prime currency can be read as an echo of Cartesian disavowal of the sensory. In various histories of conquest, this acts as a defensive response to the excavation of the violence of modernism, and of art history more generally. This is perfectly in line with the speculative turn in global financial capitalism and its various projects of governance by debt, brutal resource extraction, and sanitized diversity, all of which serve to conceal the constitutive violence of capitalism.

From 1,000 Rivers (2014), a photo series by Winslow Laroche. Image courtesy the artist.

- LAROCHE’S POST-ART

In stark contrast to Hegelian notions of art and human development as embodied by conceptualism and its afterlife, Brooklyn artist Winslow Laroche’s reading of post-art is useful for critiquing the supremacy and aesthetics of thought. For Laroche, art conceals the modernist debt to Black and brown aesthetics. In a text-to-speech sound piece featured on the inaugural episode of The Diamond Stingily Show on Know-Wave, Laroche polemically states “All white art is Black face or Brown face and all white people are cops and lurking snitches.”

He questions the post-artistic valorization of objects that fluidly move between commodified art and nugatory non-art—precisely the fungible position the slave occupies in the longue durée of the Middle Passage, situated there by an imaginary deprivation of reason. In light of slavery, such fluidity and spectacle as a “talking commodity” is old hat. Fred Moten disagrees with Marx that the talking commodity is an impossibility, given the reality of transatlantic African slavery.18 Further, Black folks have long known all sociality and aesthetics are always already subsumed into the commodity form under capitalism.

Venerating post-art fluidity only conceals art history’s antiblackness, conforming to the tradition wherein, as Keith Obadike states, “to many white artists, blackness represents some kind of borderless excess, some kind of unchecked expression.”19 Just as Picasso was titillated by the spoils of African colonization, the ostensible supremacy of thought and the corresponding fluidity of aesthetic processes relies on the erasure of modernist violence.

Laroche allows us to argue that far from living in a time “after art,” the West has not yet actually reached the conditions for art: all the West knows as “art” since the Enlightenment is an ecology of criteria for inclusion which relies on the colonial subsumption of Black and brown aesthetics. From this vantage all Western aesthetic developments simply serve to conceal this subsumption. Art objects are not useless contexts for the contemplation of timeless ideas like beauty or art itself; they work to continue the modernist project of treating non-whiteness as raw material for white speculation.20

The conditions for art as autonomous non-utilitarian endeavor will never emerge as long as art’s erasure of its own debt to Black and brown practice continues. Western aesthetic developments simply conceal the violence of modernism, betraying their anxious inability to come to terms with its reality. Autonomous inutility is simply a simultaneous escapism and market capitulation, a covertly useful endeavor of continuing modernist violence.

The supremacy of thought upholds this erasure of white debt. The West has expanded humanism to include everyone, marketizing reason and detaching it from European patrimony. In this sense traditional conservatism—from which reason as litmus of humanity emerged, and which seeks to uphold traditional European values like racial superiority and slow culture—is at odds with market conservatism, which thrives on speed and welcomes any increase in profits including multiculturalism, which it recognizes can easily coexist with white supremacy.21

Consequently, Black artists, if we choose, can operate under the assumption that art owes us. We are the true inheritors of the fluidity between art and nonart. We don’t need to make things or think or write or create value in any way for art’s patrimony: our flesh was used to build it. But we should also recognize that our inclusion into white cubes is not enough. Such inclusion is the least to be done. We must advocate that “Art art” pay dues to the marginalized bodies of aesthetic practice it violently treated and treats as raw material, and return the stolen objects that haunt its institutions.

Image courtesy Rafia Santana.

- #PAYBLACKTIME

It is instructive to consider an example that reflects Laroche’s post-art concept. #PAYBLACKTiME is a project which multimedia Brooklyn artist Rafia Santana began on November 9th, 2016. The artist describes the project as a “white-money transference system that provides free meals via Seamless / GrubHub to Black + Brown folx across the North Americas.”22

A description of the work reads: All orders are paid for by the White Guilt Reparations Fund for white people who ask “What can I do?” during a time when we have heavily publicized evidence of their race’s direct connection to the continuous suffering and disenfranchisement of Black / Brown people worldwide.

In an interview with FELT Zine, Santana states that the project’s name is “a play on the phrase ‘Payback Time,’ and also a demand to pay back black people for the hundreds of years of free labor and continuing trauma in the US alone. It is time to pay back / pay black.” The project not only offers white audiences an easy way to make concrete change, it translates the call for reparations into a service answering a need anyone could understand—hunger—and brings the audience into the conversation of what America owes Black people.

When I asked via Facebook chat whether #PAYBLACKTiME was art, Santana responded that “I haven’t thought of it specifically as art but everything I do is art I guess.” In its banal fluidity between art and non-art, and its delegation of audience and aesthetics into potential financial utility in service of feeding Black and brown people, #PAYBLACKTiME exemplifies Laroche’s post-art. It rejects the modernist premise of art’s autonomous uselessness, which is just complicity with white supremacy and a fantasy of escape from the constitutive violence of art and capitalism. #PAYBLACKTiME calls on its audience to recognize the aesthetic value in the concrete, useful act of paying for non-white people’s food. Rendering aesthetics as utility reveals the covert utility of the modernist art object: the hoarding of resources stolen from conquest, which must be redistributed.

From we need the memories of all our members, a show by South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape at HKS (Bergen, 2015). Image courtesy the artist.

- WIKIAFRICA

This essay has concerned itself with the Middle Passage and its afterlife, but Africans who remained on their native lands also faced and continue to face violent colonization processes orthogonal to that of the New World.

Wikipedia is touted as a digital democratization of information, but it often exhibits mob mentality, and its acceptance requirements can be exclusionary of information that does not fit the dominant paradigm. In particular, Wikipedia echoes the general lack of information online about Africa that one would expect from a digital sphere dominated by Western concerns. According to Wikipedia, Africa is the world’s third largest market and the most culturally diverse continent, “and yet it has the lowest and least informed profile of any region on the Internet; moreover, what does appear is often selective, lacks context and reinforces outdated stereotypes.”23

As Tabita Rezaire discusses in her video piece Afro Cyber Resistance, the Cape Town-based collective Chimurenga experienced “the controlling and geographically biased architecture of the internet…Engaged in cultural African history and theory, they tried multiple times to upload African content onto Wikipedia, so as to Africanize the world’s most visited online encyclopaedia and fill the lack of information online about the continent.”24 Elvira Dyangani Ose notes that many of those proposed entries were rejected, some “because their relevance was not proved, others because the style or tone of those entries was too personal or not deemed appropriate to the world’s most ‘open’ Internet platform.”25)

Founded in 2007 by nonprofit lettera27 and contemporary art platform Africa Center, WikiAfrica is a collaborative project aimed at generating content sourced from Africans for publication on Wikipedia. Acknowledging that Wikipedia’s content restrictions are an accessibility issue, WikiAfrica conducts workshops and training, engages field experts, and deploys other initiatives (such as Wiki Loves Women, in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut) to facilitate and encourage the publication of accurate, respectful information about Africa onto Wikipedia. The project intends to exist in concert with efforts to increase African internet access, which in June 2016 consisted of around 340 million online users, or 28.7% of the population.26

There is a long way to go, but the production of true information about Africa, sourced from real Africans navigating Wikipedia’s oppressive informatic norms, is valuable groundwork for dispelling anti-African stereotypes and increasing online African representation. Since one dimension of reparations involves knowledge transfer and the violence of in/visibility, WikiAfrica is a good rebuttal to the potential replication of Hegelian anti-black fantasies of Africa.

Though the project is a collaboration between a nonprofit and a contemporary art platform, it is not necessarily art, shirking aesthetic concerns to focus on the project of Africanizing Wikipedia and increasing digital literacy. As Rezaire states: “even if this endeavour is not thought of or seen as Internet Art per se, it can be understood as an online platform for active social resistance against occidental hegemony and online information control.”27 The art / non-art fluidity of WikiAfrica is not new to the African scene, and neither is its treatment of aesthetics as secondary to utility.

manuel arturo abreu, Herramienta, 2016. Aluminum can, soursop juice, tallow candle. Image courtesy AA|LA Gallery.

- BLACK RECLAMATION OF CRITICALITY

Reparations has a fiscal and resource access dimension as well as a representational dimension, but it also has a theoretical dimension. To stand against the supremacy of Western thought begins to lay the ground for the reclamation of critical aesthetics against European reason’s history of Black dehumanization. Black feminist literary critic and theorist Hortense Spillers argues that the Black position is the critical position: “Because it was set aside, black culture could, by virtue of the very act of discrimination, become culture, insofar as, historically speaking, it was forced to turn its resources of spirit toward negation and critique.”28

At a moment when criticality is so “in,” Black criticality remains violently punished and pilfered. Its reclamation from assimilation to Western modalities becomes imperative. While complete non-assimilation to Western thought may be unavoidable due to the coloniality of the world, rejecting thought itself remains a possibility—fuck thought, fuck that—but it doesn’t necessarily respond to the central problem.

Instead, we might look deeper into the utility of thought itself, its use as a litmus for humanity to dehumanize Black and brown people in service of conquest. The institution of thought represses the stark fact that dehumanized people, historically argued to lack reason, are in fact thinking humans. We can recalibrate the situation along the lines of Lewis Gordon: “Blackness… reaches out to theory, then, as theory split from itself. It is the dark side of theory, which, in the end, is none other than theory itself, understood as self-reflective, outside itself.”29 (Gordon 2010: 196-8).

Building on this, Jared Sexton argues that “1) all thought, insofar as it is genuine thinking, might best be conceived of as black thought and, consequently, 2) all researches, insofar as they are genuinely critical inquiries, aspire to black studies. Blackness is theory itself, anti-blackness the resistance to theory.”30 Just as the autonomous inutility of art remains impossible until the West repays its debt to Black and brown aesthetics, so does a true theory detached from the sensory remain impossible until theory reconciles its antiblack dehumanizing uses.

Image courtesy of @delashereen.

Reclaiming criticality as properly Black may mean grappling with the possibility that, as Hortense Spillers argues, “black culture—as the reclamation of the critical edge…has yet to come.”31 If Black culture as reclamation of criticality’s Blackness is a horizon, it remains clear that the intersection of Black assimilation to American imperialism and American genocide of Black people engenders what Joy James calls a dead zone. “The nexus at which black achievement meets black genocide appears as a conceptual void.”32

Art in a Larochean sense, as the conditional inclusion of Black artists to reify power and conceal modernism’s debt to non-white aesthetics, is one such conceptual void. This foregrounds the necessity for action without a complete or cogent analytic, an imperative to redistribute resources now and ask questions later—or rather, an imperative to see such action as theory itself: repairing the schism between ‘thinking’ and ‘thinking in black.’

James acknowledges the stumbling and illegibility involved in deploying an analytic from the dead zone: “The intersection is unlit…as we repeatedly cross our own past while projecting a real and imagined future as critical thought radically invents meaningful engagement.”33 While the reclamation of Black criticality remains but a horizon, we can look to projects like #PAYBLACKTiME and WikiAfrica as examples of subversive engagement with the always already commoditized technics of sociality in order to repair the injustices and unequal access faced by Black artists around the world. In their fluid status and delegation of aesthetics to a utilitarian reparative role Black artists challenge the contemporary continuation of modernist violence, in line with a Black post-art to lay the groundwork for the reclamation of criticality’s Blackness.

Footnotes

1. Joselit, “Heritage and Debt” (lecture, Mack Lecture Series, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, December 3, 2014), February 12, 2015

2. As part of Home School—a free pop-up art school I co-facilitate in Portland—I taught a class called Contemporaneity: building a better white supremacy, which further explores these ideas.

3. “I call ‘standard’ those aesthetics whose principles (1) are recognized and accepted, across a number of variations, by institutional and academic communities and which thus constitute the object of confirmed knowledges; (2) whose principles define either a foundation for art or a philosophical description of art or, more generally, a normality and a normativity; which is to say (3) a determinism of the reciprocal causality of art and of philosophy. It poses well known questions of the type ‘What is art?,’ ‘What is the essence of art?,’ ‘What can art do?,’ and it believes it can answer these questions with certainty. In accordance with these questions, standard aesthetics describes the styles, forms and historical epochs of art in a broadly realist manner, for it believes it is possible to define both art and philosophy.” Laruelle 2012

4. Hegel, Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Arts, Vol. 1, 10. With respect to art, Hegel focuses on the contemplation of beauty, but for our purposes a tautological definition of art as whatever is called art works fine.

5. Kaminsky, Hegel on Art: An Interpretation of Hegel’s Aesthetics, 8

6. Kaminsky, Hegel on Art: An Interpretation of Hegel’s Aesthetics, 27.

7. Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 102.

8. Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 98.

9. This text was at first was handed out as a leaflet but is generally wall-mounted behind glass today.

10. Matthew 26:26-28 NIV.

11. Craig-Martin, Landscapes, 20.

12. Descartes, Discourse on the Method of Correctly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences, 48.

13. Negarestani, “The Labor of the Inhuman, Part II: The Inhuman.”

14. Hegel, The Philosophy of History, 111-12, 117.

15. The work of Orlando Patterson, Hortense Spillers, Sylvia Wynter, Saidiya Hartman, and others lay the ground for the emergence of the Afropessimist texture of thought. The former’s analytic shift of focus toward the position of the slave allowed for the work of Frank Wilderson III, Jared Sexton, Christina Sharpe, and others to build on arguments about the fungibility of the Black body in racial capitalism, the social and ontological death of Black life, and the structure of multiracial global antiblackness. A simultaneous analytic trend of “black optimism” ostensibly in contrast to Afropessimism is exemplified by the work of Fred Moten and others. However, Sexton convincingly argues that the two are not so distinct, as embodied in the paradox that “black social death is black social life.” Both Afropessimism and Black optimism engage the impossible possibility of Black existence as such. Further, “the object of black studies is the aim of black studies,” that is, the horizon of Black liberation from social and ontological death. Sexton continues: “The most radical negation of the anti-black world is the most radical affirmation of a blackened world. Afro-pessimism is ‘not but nothing other than’ black optimism” (Sexton, “Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts”).

16., 17. Murrell, “African Influences in Modern Art.”

18. Moten 2003: 6

19. Keith Townsend Obadike, interview by Coco Fusco, in Mendi + Keith Obadike, September 9, 2001

20. abreu, “Notes on the Garage Residency.”

21. Sexton, Amalgamation Schemes: Antiblackness and the Critique of Multiracialism.

22. $6,398.79 = Total orders and dollar amount for #PAYBLACKTiME as of December 26, 2016

23. Wikipedia contributors, “Wikipedia:WikiAfrica,” Wikipedia

24., 27. Rezaire, “Afro Cyber Resistance: South african internet art,” 188.

25. Dyangani Ose, “Poetics of the Infra-Ordinary” (lecture, OCA Norway, Oslo, March 14, 2012)

26. Miniwatts Marketing Group, Internet Users in Africa March 2017

28. Spillers, “The Idea of Black Culture,” 28.

29. Gordon, “Theory in Black: Teleological Suspensions in Philosophy of Culture,” 196.

30. Sexton, “Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts”.

31. Volcovici, “The Power Trip of the Black Exceptionalist in Space-Time.”

32. James, “The Dead Zone: Stumbling at the Crossroads of Party Politics, Genocide, and Postracial Racism,” 460.

33. James, “The Dead Zone: Stumbling at the Crossroads of Party Politics, Genocide, and Postracial Racism,” 476.

Bibliography

abreu, manuel arturo. “Notes on the Garage Residency,” SFMoMa Open Space: Work on Work Blog. September 14, 2016.

Descartes, Rene. A Discourse on the Method of Correctly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences. Translated by Ian Maclean. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Dyangani Ose, Elvira. “Poetics of the Infra-Ordinary.” Lecture, OCA Norway, Oslo, March 14, 2012.

Gordon, Lewis. “Theory in Black: Teleological Suspensions in Philosophy of Culture,” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 18.2 (2010): 192-214.

Hegel, GFW. Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Arts, Vol 1. Translated by T. M. Knox. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1975.

Hegel, GWF. The Philosophy of History. Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books, 2001.

James, Joy. “The Dead Zone: Stumbling at the Crossroads of Party Politics, Genocide, and Postracial Racism,” South Atlantic Quarterly 108.3 (2009): 459-481.

Joselit, David. “Heritage and Debt.” Lecture, Mack Lecture Series, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis , December 3, 2014. February 12, 2015.

Kaminsky, Jack. Hegel on Art: An Interpretation of Hegel’s Aesthetics. New York: SUNY, 1962.

Kaprow, Allan Kaprow. Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Laruelle, Francois. “The generic orientation of non-standard aesthetics.” Lecture, Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, November 17, 2012. October 21, 2013.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Murrell, Denise. “African Influences in Modern Art.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. April 2008.

Negarestani, Reza. “The Labor of the Inhuman, Part II: The Inhuman.” e-flux Journal #53. March 2014.

Obadike, Keith Townsend. “All Too Real The Tale of an On-Line Black Sale.” Interview by Coco Fusco. Mendi + Keith Obadike. September 9, 2001.

Rezaire, Tabita. “Afro Cyber Resistance: South african internet art,” Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 12.2 & 3 (2014): 185-196.

Sexton, Jared. Amalgamation Schemes: Antiblackness and the Critique of Multiracialism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Sexton, Jared. 2012. Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts. Lateral 1. Cultural Studies Association.

Spillers, Hortense J. “The Idea of Black Culture,” CR: The New Centennial Review 6.3 (2006): 7-28.

Volcovici, Geoffrey. “The Power Trip of the Black Exceptionalist in Space-Time.” Black Quantum Futurism. January 1, 2017.