The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Hanna Girma: I know you work in a variety of different mediums and navigate multiple personas, how does your process vary when creating as Mhysa, E. Jane, SCRAAATCH, and E. The Avatar?

E. Jane: SCRAAATCH isn’t a persona of mine. SCRAAATCH is the collaborative music/performance project I work inside of with my partner, chukwumaa a.k.a. lawd knows.

E. The Avatar was a project I did in grad school. She was an early persona, conceptualized as intelligent code meant to run online/in cyberspace for eternity and hang out with humans. The persona was mostly communicated through the episodes and I enjoyed dryly delivering her lines as though the code wasn’t sophisticated enough for her delivery to be smooth. Her lines were generic as though she was coded with only a limited set of topics and words to use.

I think that at this point, at least in american capitalism, we’re all presenting personas or brands for the publics we interact with to consume. In that way, I think of E. Jane as my me, but also I do sketch out their (or my) main functions in relating to others and existing in the world and they are largely a result of my leaving a predominantly Black space in Maryland and then navigating PWIs (predominantly White institutions). In grad school, I sketched out what I thought were differences between all of my personas and was thinking I was navigating like five whereas now I navigate two really: E. Jane and Mhysa. Mhysa is also me and she allows me to be a part of myself I think white institutions tried to smother. Now I keep her with me and bring her out when we’re safe to be, preferably in spaces where Black women can just be themselves without having to explain or apologize, in spaces where other Black women exist and are seen. Or occasionally in spaces where Black women are sent for (these spaces still hold higher risk for her but capitalism demands we all take risks).

Mostly we (E. Jane and Mhysa) work together in my studio, both taking turns in the creative process when we’re needed. Mhysa is more about music and feeling and making things that feel and E. Jane deals with the more institutional approaches and deconstructing them, whereas Mhysa doesn’t like to think about those spaces and would much rather think about nightlife. Both would like to see themselves as healers, both believe in magic, both believe that love and care matter more than reason.

Lavendra/Recovery Iteration No.2 (2016). Installation; Two-channel video, sound, light, Swarovski crystal nail art rhinestones, cellophane, milk crates, bubble wrap, plastic, paint pen, tape, paper, iridescent wallpaper, love.

HG: The atmospheres of your videos and installations seem to navigate between softness, intimacy, and sterility. From the materials you use like plastic boxes, cellophane, and bubble wrap to the fragile yet powerful ’90s black divas you explore, can you talk about how you source your materials and create these realities?

EJ: In my early work I thought about color a lot less and was thinking about materials based on conceptual needs. Like I started using bubble wrap because I wrote in my journal in 2012 about my mom treating me like I needed to be wrapped in bubble wrap or I might break after she hospitalized me several times the previous summer and kind of treated me like a defenseless princess because I was diagnosed as Bipolar I. Now I see fragility quite different and I think ableism is a bigger issue than being fragile. I am a very fragile person and that’s okay. I’m also quite malleable which I think fragility also points to, because if something fragile breaks, it can shatter but it can also just change form or even be reformed from the pieces.

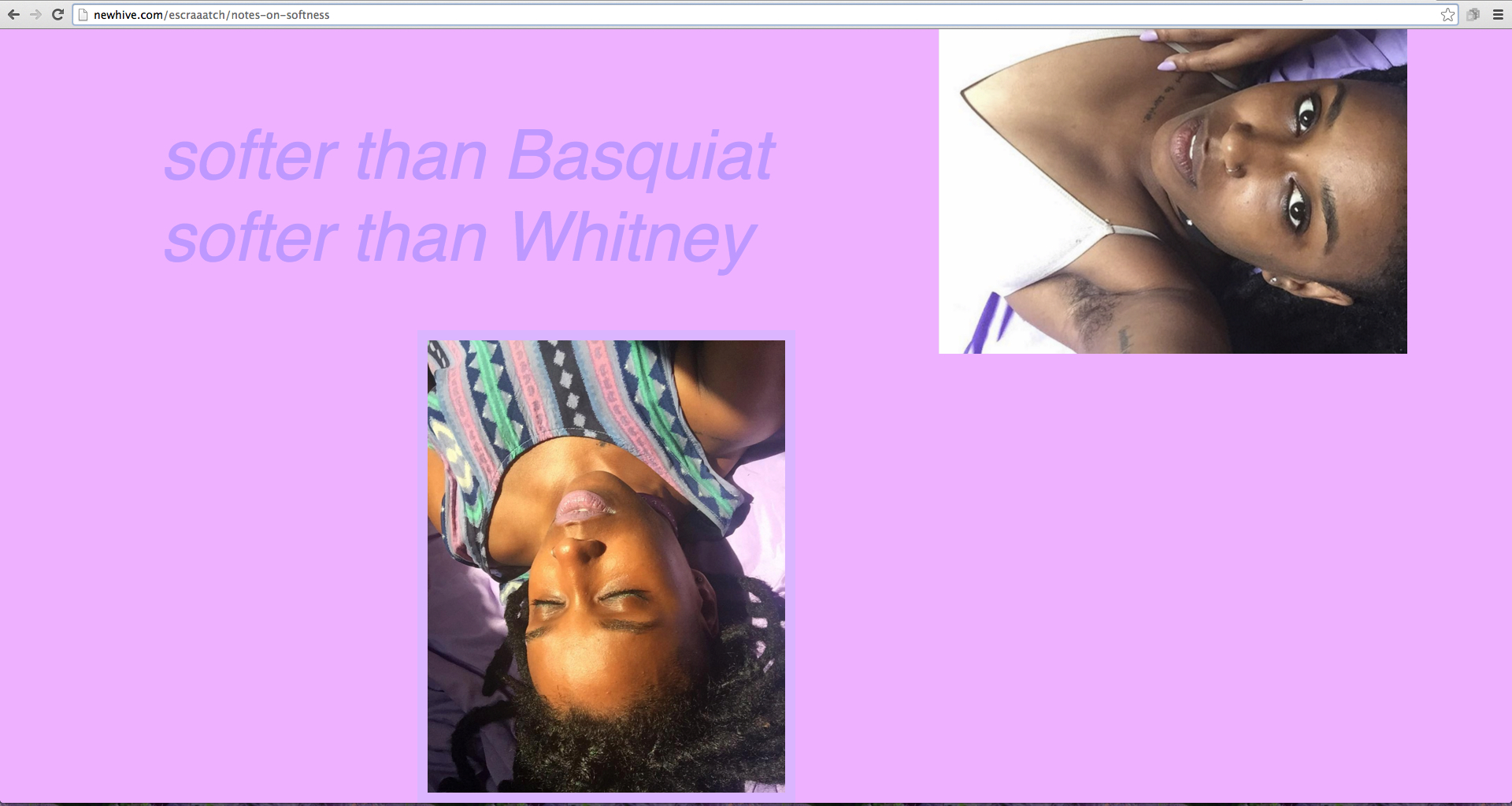

Notes on softness, (2016). Installation; Two-channel video , sound, light, swarovski crystal nail art rhinestones, cellophane, milk crates, bubble wrap, plastic, paint pen, tape, paper, iridescent wallpaper, love.

I used the plastic sparkly boxes in one of the pieces in Lavendra because they were right for holding/keeping the images of the Black divas. I wanted to keep their images in pretty boxes, and thinking with my child self, who I have to consult on all my projects dealing with dreaming and optimism, I decided they should be held in purple sparkly boxes. Then I searched for just that on Google and found those boxes and they felt right. I liked the type of plastic they were made from also because it’s used to make a lot of things, it’s a ubiquitous type of plastic. The place I bought them from stopped selling them, too, and I find things like that interesting.

Lavendra still exists inside of this reality, it’s just not on Earth. It engages science fiction to theorize the evolution of the power of the Black Divas voice. I think often about how to build beauty and good on top of this current reality, since this is the one we’ve been given. I think about how to build for the future, since the future is a new reality we’re all always building together. I like to create phenomenological experiences through materials, thinking really about how different colors, lighting and texture change a space and manipulate how you see your reality. I’ve also been thinking about pink and purple in relation to how they frame bodies and spaces and purple in relation to Alice Walker’s Womanist definition, and branching out to other colors from there to generate a palette to work in.

HG: In NOPE (a manifesto) you state, “We are beyond asking should we be in the room. We are in the room. We are also dying at a rapid pace and need a sustainable future.” Do you see cyberspace as a type of sustainable future? Is the digital realm a space of of safety, method of survival, or another frontier and how do you quantify your practice outside of the digital realm?

EJ: No, cyberspace is no one’s sustainable future because its infrastructure is incredibly precarious. I have no idea how they intend to sustain all the electrical cables and metal boxes in the ground that store our so-called immaterial cyberspace and the “cloud”. Also how cyberspace is made is incredibly violent to the Earth and the humans who mine the Earth’s minerals to make our computers, who are crowded in factories to make many of our phones, and only about 40% of the world has access to the internet. These are some of the saddest realizations I’ve had about the internet. Also, it is not a safe space because hacking is too easy.

It can be a part of a method of survival. The best part of the internet for me is how it allows to me to stay connected to my communities even when I’m unable to see people in meatspace that I wish I could see more often. I like being able to work in my studio and see my friends in other places around the world and what they’re up to online, reach out to them so that we can be there for each other and strengthen each other whether it be with an emoji or a phone call. I like making plans to meet my friends online and feeling like we saw each other yesterday even if we were on different coasts yesterday because we were still together online. I like how information spreads online, though that’s starting to change as Facebook and IG algorithms silo off information to stifle awareness. Because the information seems to only ping back and forth between specific groups of people, it can sometimes make you feel like everyone in the world is on the same page, until you realize there are so many circles of people with different opinions sharing information that bolster those opinions (be they ethically good or violent) and there are all the people not online being informed by television news which mostly skews the truth for financial gain.

Capitalists really control the internet. As soon as Tumblr became a hub for interaction, companies began wondering how to capitalize on it, and then Instagram and, of course, Facebook. I get messages asking me to be a brand ambassador for random companies that have nothing to do with why I post online. It’s already been swallowed by this current dystopia, but I think that’s because humans control what happens with cyberspace and technology. Originally a “computer” was the person who made calculations and somewhere down the line the machines started being branded as the “computer” and we the “user,” but people still design the computers, write the code that makes their interfaces and determine what they can do. Therefore, I’ve started to think less about what the technology will do in the future, and more about who determines what the technology can do, and what they intend to do with it. I’m starting to think of capitalism as this virus that capitalists teach to evolve around new subcultures in order to find profit, and then I wonder how I can evolve and how we can evolve to counter this evolution.

Alive (Not Yet Dead) (install) (2016). Interactive NewHive installation.

Since before the dot com bubble, capitalism has been directly engaging cyberspace. And the social media platforms we’ve been using to be online are the newest frontier for capitalism. Since capitalism is vested with way more power than the people, I’m not exactly optimistic about the future of the internet as a space for humans to go for safety.

Also, towards the end of grad school, I started to realize how alienated I was to my physical body and how unhealthy I was feeling because of that alienation. I was forced to remember that we humans still have physical bodies we must tend to and—like plants—they need sunlight and water and fresh air. Cyberspace has no actual physical component to house or nourish our bodies, so we still have to make physical hiding places in meatspace and ideally I would love for Earth to have a more sustainable future, though I fear many people with power have already given up and are trying to get their tickets to the next best planet.

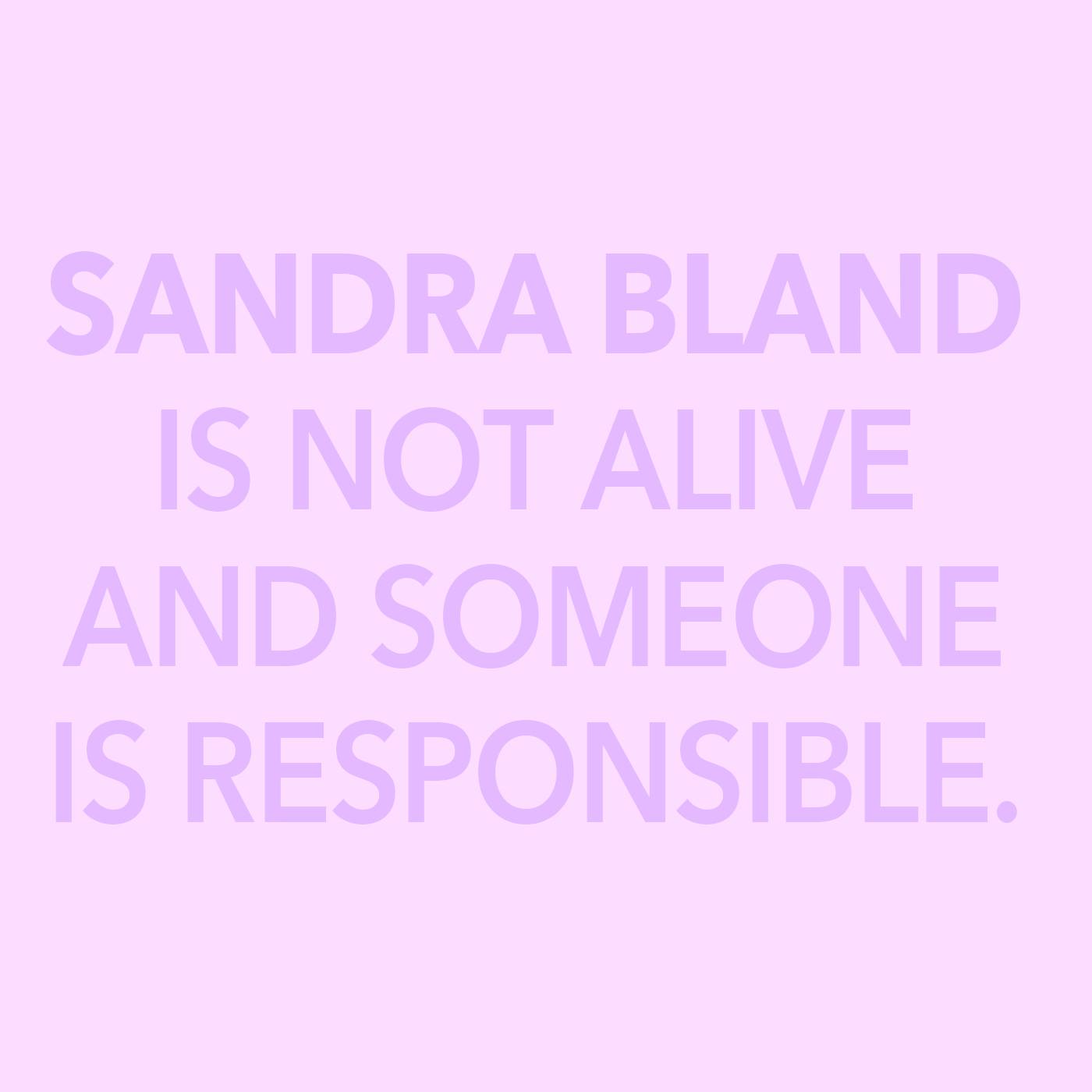

HG: Much of your work is punctuated by resistance, refusal, and love. Can you tell me about your project #Notyetdead and how it relates to your broader practice?

EJ: The #Notyetdead project was started in the winter of 2015 after I found out that Brian Encinia wouldn’t be charged for the murder of Sandra Bland. When he wasn’t indicted, I was outraged but tired of writing things on Facebook about how outraged I was because it felt ineffective. So I decided to make a background for photobooth with the word ALIVE at the top and to take photos with it and then I asked other Black women to do the same via Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter and asked them to hashtag the images #Notyetdead in relation to Roxane Gay’s article “On the Death of Sandra Bland and Our Vulnerable Bodies,” published in the The New York Times Opinion pages in the summer of 2015. Gay says,

In his impassioned new memoir, “Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body — it is heritage.” I would take this bold claim a step further. It is also traditional to try and destroy the black spirit. I don’t want to believe our spirits can be broken. Nonetheless, increasingly, as a black woman in America, I do not feel alive. I feel like I am not yet dead.

I hoped the images would show that many Black women were still alive, though a part of a group feeling #Notyetdead, in an effort to resist the public image that we were only dead, dying or being brutalized.

Sandra Bland is Not Alive And Someone Is Responsible (2016). Instagram Post

With the help of a commission from Ryan Hawk at University of Texas at Austin in 2016, I then turned the images into a larger installation where I created a NewHive page with several 3D spinning graphics of the word ALIVE. That version was installed in a show called Queer Terrortories that Ryan curated, where people could scroll omnidirectionally through the images across multiple panels to create the feeling that many of us are in fact still alive. This work is trying to strengthen the Black spirit, to remind us that there is good news also because the news has felt so bad since 2012 and it seems to keep getting worse. My broader practice also involves trying to protect and nourish the Black spirit because we need our spirits intact if we’re going to continue surviving these times.

HG: Your recent show at American Medium is the third iteration of Lavendra. With this ongoing project what are you hoping to accomplish? What is the significance of repetition and ritual in your work?

EJ: The work in my solo show Lavendra was also work that tried to strengthen the Black spirit by making beauty with/in the name of Black culture, a thing I already see as very beautiful and very baroque at times. The work was started, again, to counteract all the negative images and resist a larger white supremacist imaginary that imagines us only dead and dying. I wanted us to see ourselves as only we can, in the tradition of artists like Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems and I also wanted to territorialize space for us, and keeping space I think is a major part of resistance, like holding down a fort.

Repetition and ritual in my work are important as they are the things that strengthen a culture, to make ritual is to make culture as culture is made up partially of rituals. In the video Saved.mp4 (installed in the storefront window of the gallery), I wanted to show a ritual of keeping the images of these women, of loving them and folding them like keepsakes to be safe in pretty boxes for a long time. In the act of repetition, I hope to encourage others to do the same, keeping I mean, and also suggest that this act is ongoing, relentless. I like video because a video can go on longer than your body can, because it can be looped and there a gesture can really appear infinitely enacted.

HG: Can you talk a bit about your thoughts on softness, particularly softness as a political act for black femmes?

EJ: I want to start by saying I identify as a femme because I am queer and grew up around gay women that identified as femmes because they liked girls and wore dresses. I’ve been finding myself getting back into being a queer-identified person that is engaging feminine aesthetics and gestures.

As a Black woman, I think the performance of a soft femininity—that is, a femininity rooted in delicateness, rest and feminine labors (though these labors are still oppressive to all women)—is denied us far too often because of misogynoir. In particular, I’m thinking about Black american slave-descendant working-class families that maybe function under “strong Black women” matriarchies or just expect a woman to be a strong, silent “mule,” to quote Alice Walker. I think a lot about Alice Walker, her thoughts, her essays, and the film The Color Purple in relation to Black women and softness. I think about how Celie was just expected to work and not have nice things and Shug Avery was judged as “fast”/loose for getting those things through professional entertainment and relationships with men.

I think about what it would feel like for a Black woman to possess a soft, non-physical-labor-intensive femininity and still be safe in a way I couldn’t even imagine being after a certain age. I remember my father judging me because I was so good at sitting still and being pretty in social situations and how, because my mother didn’t make me clean the house very often, I refused chores as much I could and was seen as a bad “woman” because of this. I think about how softness is generally used against Black people, especially by one another, because we’re told we have to be hard to survive. I think that sometimes that hardness inadvertently kills/harms us because that kind of repression—like unreleased cortisol from not crying—has actual negative effects on the body.

Things like crying, resting, and cultivating aesthetic beauty (if you’re interested in that) or even just taking basic care of/being careful with your body and trying to be “soft” at a time when the world expects you to react with hardness to it being so brutal could maybe be radical. Engaging in this kind of softness might help reinforce our spirits because we’re responding to the climate by building ourselves up when tired, crying/venting when we’re frustrated/sad and caring for our bodies when we’re weak. Doing these kinds of things instead of solely doing things like working ourselves into the ground, directly confronting every instance of oppression (in conversations, random interactions, online etc.) can run counter to the kind of exhaustion and destruction that is practically expected of Black women only.

I am so angry, I have so much rage, but it becomes physically unhealthy for me to express it sometimes.

It’s actually much more to my benefit to remain calm in my rage, to sit pretty in my rage and start planning a better future rather than letting my anger bring me down to a toxic space. I think also about resisting femmephobia by performing feminine gestures and engaging in feminine culture despite them being perceived as “less than” or not “serious” things to concern myself with. In the Womanist definition, Alice Walker says that a womanist prefers women’s culture and I also see softness as a part of women’s culture.

Here again, I think about The Color Purple. I consider Sophia and how if she had said something like, “I’ll think about it” to Ms. Millie, she might’ve avoided that fight (and jail) and had more time with her children and family. I think about how my goals involve resisting the efforts of white supremacy to tire me out, disconnect me from my kin and lead me on a path of distraction where I’m fighting to show I’m human instead of living my life. Working tirelessly to prove one’s humanity as a Black person is also known as John Henryism, which Claudia Rankine discusses in her innovative work, Citizen. In the book she describes it, “Sitting there staring at the closed garage door you are reminded that a friend once told you there exists a medical term — John Henryism — for people exposed to stresses stemming from racism. They achieve themselves to death trying to dodge the build up of erasure.”

It’s not passive resistance, but rather just as evil has gotten banal, maybe Black rage has to get soft to compete. Like how Judith must’ve been in the bible story where she convinces Holofernes to let her in his tent, before she cuts off his head. I am also indulging in softness as a Utopian demand, coming from a history where enslaved Black women had their fingernails pulled off if they were caught painted.

Honestly, I’m just trying something because I have to keep going. I’m trying not to give up and die because the world is a violent scary place right now and I fear for my life and the lives of other Black women and POCs, in general.

Grown (detail) (2016). Archival inkjet print on foamboard, swarovski crystal nail art rhinestones, gel medium, led lights, lighting gel, love.

Questionnaire

Age: 26, turning 27 in June

Location: Philadelphia, PA

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology? When I was 17 I started playing with video software on my laptop but began taking the technology more seriously as a creative tool when I was around 23.

Where did you go to school? What did you study? I went to Marymount Manhattan College for undergrad where I studied Art History, English (with a focus on poetry), and Philosophy mostly. I did a semester abroad in Paris where I studied black and white photography, art history, life drawing and french, after a year of taking french in school.

I studied Interdisciplinary Art in grad school at UPenn, with a focus on performance and video. I started studying under Sharon Hayes my second year and she’s still my mentor now.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? My partner and I are in a performance/music duo called SCRAAATCH and we perform often and generally that’s how I make rent. Also maybe going on tour soon.

Past on cv:

June 2012 – June 2014 Performance Art Documentarian, Washington, D.C.

Jan 2013 – June 2013 Gallery Intern, International Arts & Artists’ Hillyer Art Space, Washington, D.C.

June – Aug. 2011 Public Relations Intern, Christie’s Auction House, New York, NY

June – Aug. 2010 Program Services Unit Intern, New York Dept. of Cultural Affairs, New York, NY

June – Aug. 2009 Manuscript Division Intern, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

I also worked various types of retail when I was about 17, throughout undergrad and my time afterwards until I was 23 when I went to grad school. I worked at American Apparel, Anthropologie, and then vintage shops and buy/sell/used shops.

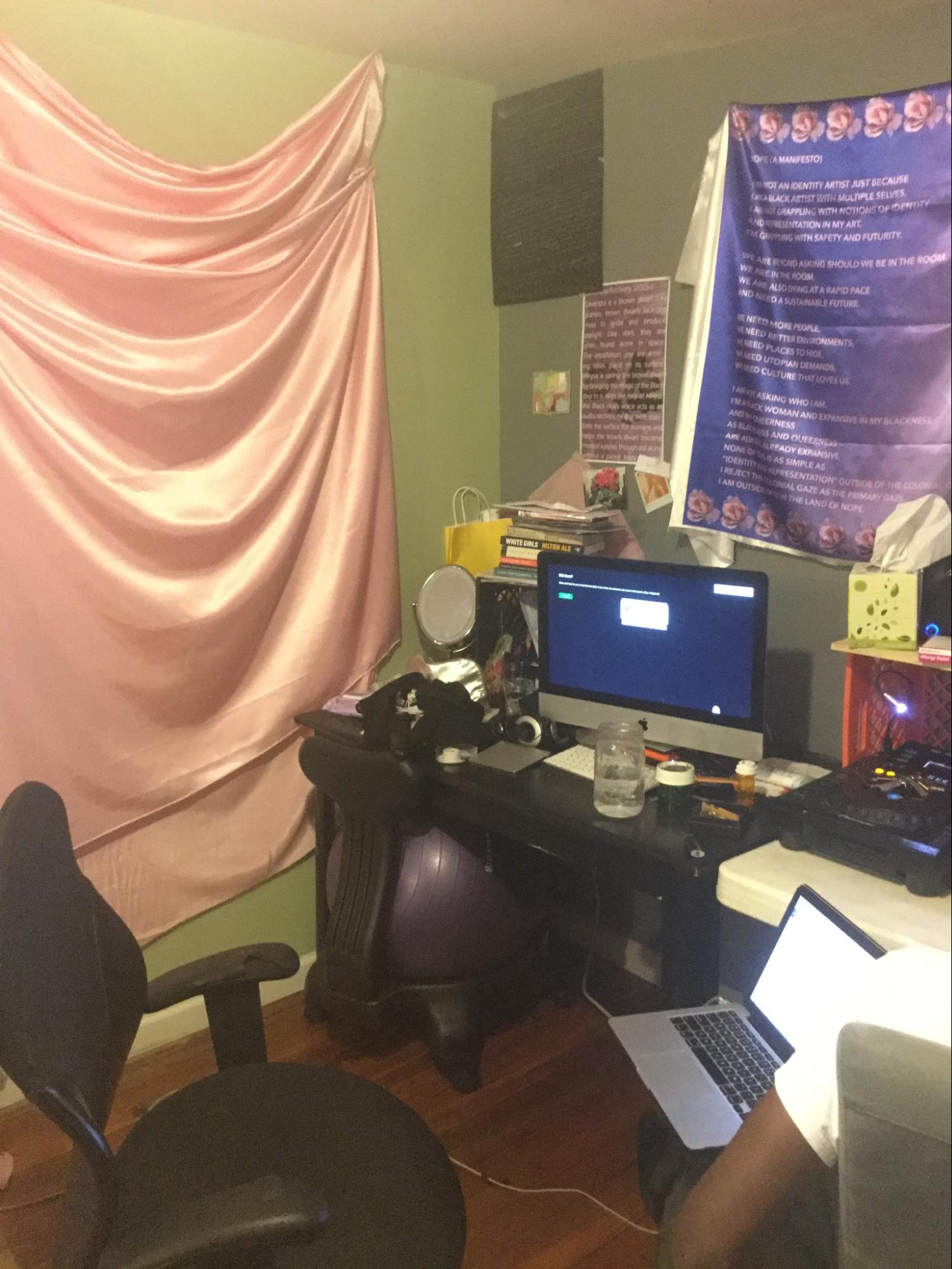

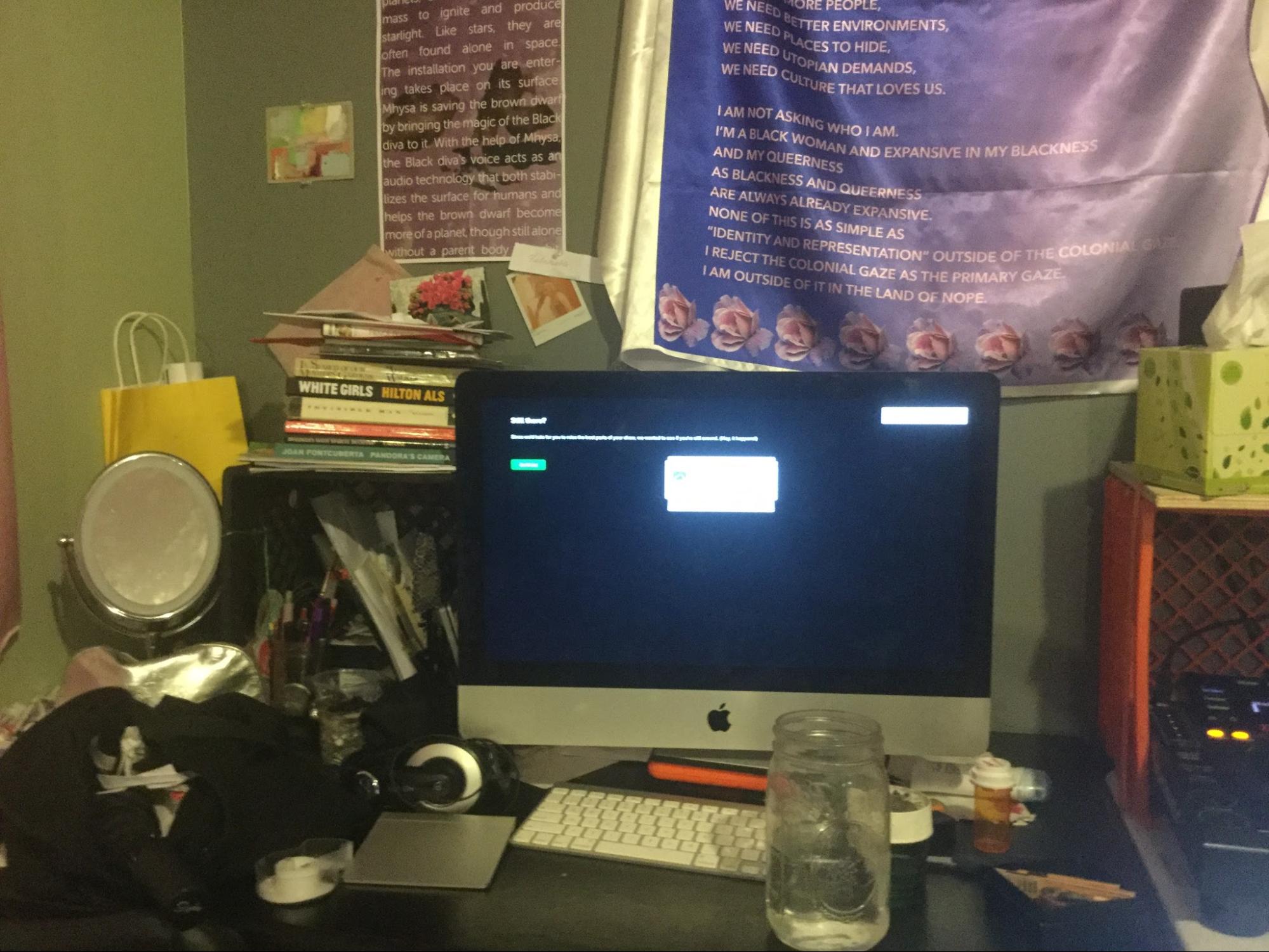

What does your desktop or workspace look like?