Jeffrey Alan Scudder, 2017.9.8.18.25, 2017.

The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Simone Krug: So much of your work is concerned with the idea of the infinite or its opposite, the finite space of the limited, the never-ending picture plane, the canvas you can zoom into continuously, where you're sent deeper and deeper into the pixel. You've talked about coming to terms with the limits of the system and using it as if it's an instrument. In some works, you hide the edges so you can draw across a single drawing as if it were many. How do these ideas inform your work?

Jeffrey Alan Scudder: In my work, I consider three ways of making a picture. They're related to the scale of the viewer and maker in relationship to the scale and quantity of their media. We can give them each a name: the arrangement, the mark, and the scan.

Imagine that you’re on a beach. You collect some small rocks. You can place these on the ground to create a picture of a smiley face or “X marks the spot” or something like that. You can reset the rocks into as many configurations as you like. This is the level of the arrangement. Graphic and interior designers often prefer to work this way. Here we get the idea of something being done, undone, and redone.

Find a dry area of coarse sand. You can make marks in the sand with your finger. This is the level of the mark. We use this level of picture making for everything from handwriting to mathematics and architectural planning. It is at this level that we get the idea that something can be erased.

Walk along the water where the sand is wet and smooth. Look down by your bare feet. Do you see the impressions they make? Not only can you make out your toes in detail, but you didn’t even decide to make a picture in the first place. It happens automatically. This is picture making at the level of the scan. It’s here that we obtain the idea of surveillance and deletion. We use this level for everything from photography to fingerprinting.

.jpg)

Just Another System, AMS Resolution Diagram, RISD.

Regardless of the universe being finite or infinite, the higher the density of your media, the more you are able to scan. The lower the density, the more you are able to arrange. Note here that scanning is biased towards recording existing things, and arrangement is biased towards inventing new things. Mark making sits somewhere in between.

Arrangements are very portable. For example, I can say: “Collect ten rocks, this one goes here, this one goes there, this one goes next to that one…” The instructions can persist over time as a score or a recipe. But with a scan or photograph, there's so much information, I can't conveniently give you all the instructions on how to reproduce that thing. Instead, the information must be stored on some recordable medium, like soft clay or hard disk. The scan can be deleted and never retrieved! It is a fragile thing. Whereas the arrangement approaches infinity in its durability, the scan approaches infinity in its resolution or fidelity.

SK: Are there specific works where you think about that idea of the infinite more broadly?

JAS: Computers are actually very limited in their capability, but they are great at illustrating the infinite. The Dot, this one piece of software that I've been performing with, is all about this.

Dot Demo & Tumpin Trailer: July 2017 (https://tumpin.left.gallery).

In most creative software, you have sliders and controls; there's a range between a minimum and a maximum. For example, we often pick RGB values by sliding virtual handles from 0 to 255. In Photoshop, you can pan across an image, but then you can shift the image off the screen so you don't see it anymore. There is a keyboard shortcut to get it back into your view. You can zoom in and out, but only so far in each direction. And further you can only go in one direction, until you can’t any longer. Then you have to go backwards. With the Dot, I avoid this interface pattern entirely. I turn every control into a circular loop, so that you can slide in one direction continuously and eventually return to where you started. It's a visual trick, but I think it's an important trick because it creates a more fluid, user-friendly idea of navigating an image. Computers are great at looping! The Dot was also used to record my recent picture Tumpin, a continuously cycling system of 128 dot arrangements.

Screenshot from Tumpin.

In my digital paintings, I like to define some spatial and durational limits before drafting. A digital painting is a record of interactions, stored in a visual frame.

SK: Let’s talk about recording. You've noted in the past that you see drawing as a form of documentation. Can you elaborate on your interest in the idea of your pictures as a record, or of your paintings as a recording?

JAS: I recently read this book Painting Beyond Itself. It opens with a short essay by David Joselit, “Marking, Scoring, Storing and Speculating on Time,” about artists whose practices hold responses to the question of painting as record. He says that “At least five formats may be identified for scoring painting’s circulation, each with roots in the history of modernism.” One is that series or ensembles of works may eclipse the individual or unique painting. Another is that the delegation of mark making is done through various technological apparatuses. A third, that painting is made performative. The fourth, that images are made to ebb and flow in and out of pictures, which is what occurs in animation or visual software. Lastly, that painting might be staged as a souvenir of life, where the picture becomes a piece of evidence for some primary event. For example, Joseph Beuys gave chalk talk lectures and those blackboards are now hanging in museums.

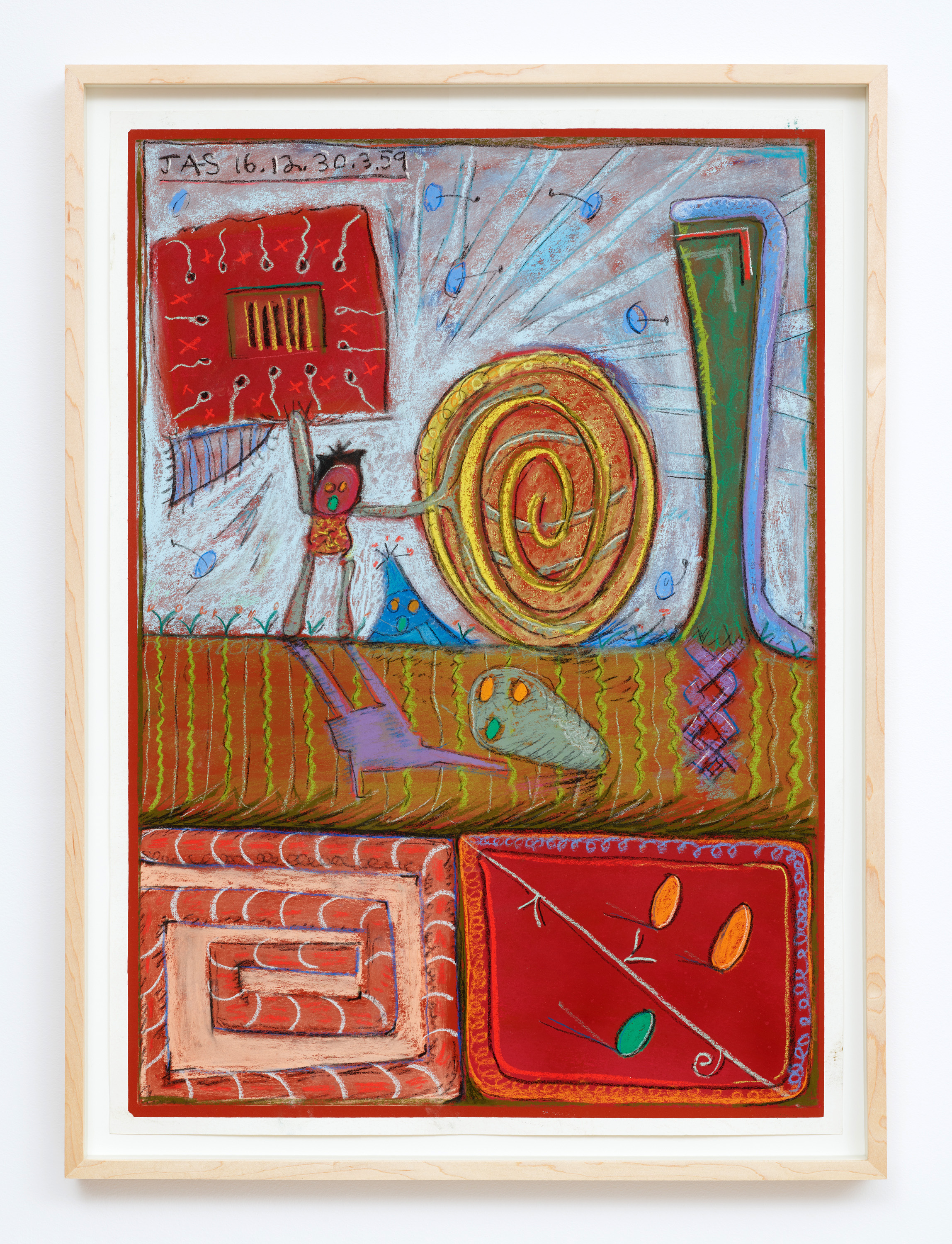

Something a bit more radical to consider is that painting is just one genre in the vast field of visual documents. In other words, what makes somebody look at an image file and think of it as a painting (or digital painting) as opposed to something else like a screenshot, photograph, or render? To think radically about painting today is to be acutely aware of how a painting may be identified as such in the set of all possible images. One identifier is visible evidence of mark making.

Jeffrey Alan Scudder, 16.12.30.3.59, 2016.

SK: So much of the history of painting throughout art history is about hiding that. About not really showing marks.

JAS: The game of hiding labor is still being played in other fields like computer graphics, video games, and virtual reality. If a Hollywood movie switches from a live actor to a computer-generated one in the same scene, that's where they're still trying to hide things. That’s where they're trying to hide their labor by making the transition seamless and passable.

I look at the iPhone and I think, where’s the work that went into this thing? Which part was made by machine and which part was hand-assembled? The labor is invisible. Even on the software side, when I call for a car or when I post something online, I don't know exactly what the servers are working on. It's a black box scenario. My phone uses the energy in its battery, but it also uses energy from the wireless network and from the software companies who provide me with their services. Today we have this whole global ecosystem that works to hide evidence of labor in its products and processes. Painting is a device that shows labor.

Jeffrey Alan Scudder, 2017.11.25.11.06, 2017.

SK: In contrast to painting with paint, you have infinite material when you work with a screen or when you work on a digital painting. How do you think about quality control with that in mind?

JAS: Digital painting comes with its own set of material limitations, usually in the form of environmental constraints like the programmed capabilities of the software you are using (a big one for me, obviously!), the number of representable colors in your output, the amount of memory or processing power available in your system, its battery life or portability. In practice, you have an infinite amount of “paint,” but a limited amount of time. I would say that you should keep everything, regardless of quality, because it is your time that's the most limited, and secure storage space, even for large work, is very cheap when compared to canvas.

SK: It seems you're more of a Marxist than you realize.

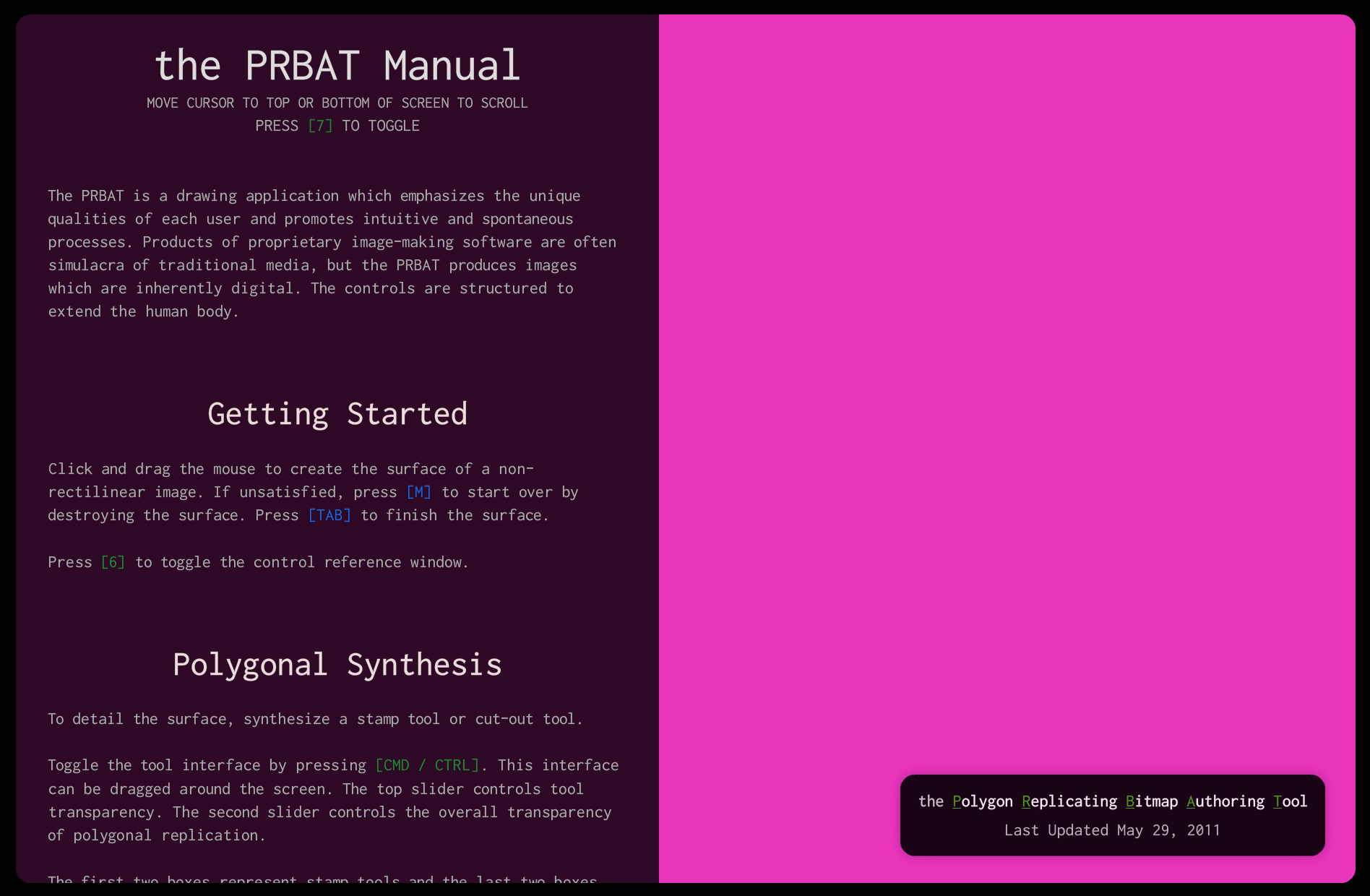

The PRBAT Start Screen.

SK: The Polygon Replicating Bitmap Authoring (PRBAT) tool was meant exclusively for your use. In other software, you think about others or a remote public use mode. How do you engage with the idea of user friendliness and how do you think about who your users might be?

JAS: When I did the PRBAT project I was also learning programming and I wanted to make my own tool for myself. I was not thinking on the level of having other users. Design-wise, when you're only thinking about yourself, you might make something really unusable for others, that nobody else wants or needs. You may even forget how to use it as time goes on, but maybe you can do interesting things with it that you couldn’t do if you were thinking of others first. The drawings that I've made with the PRBAT have been enjoyed by those who viewed them, and a good number of people have been inspired by the software, even though they don't use it. The PRBAT was certainly meant for me, but there's also an instruction manual built in.

User-friendliness is interesting because it’s a moving target in relation to programming literacy. More and more people are learning programming today. As literacy increases in the population over time, our software should become less “user-friendly” in today’s terms. If everyone’s a programmer, then our idea of user-friendliness changes. For example, we’d probably expect most software to expose a programmable interface by default. Regardless, when you design for other people you have to think of their needs. Sometimes you have to simplify things to make them more communicable.

SK: Is there a specific work that comes to mind when you talk about this? Maybe the first work you made for other people?

JAS: It's Shrub, which I made with the design studio Linked by Air. That was my first piece where I thought: I'm going to make this thing for others first, and for myself second.

SK:How does that one work?

JAS: You use the phone to point at things in space and then you draw a mark to reveal or freeze part of the camera frame. You can collage with it. Because the phone’s interface is very limited, the tool only does one thing, whereas most of the work that I made prior to that had a lot of keyboard shortcuts and was a little more tailored to my specific interests. Usually the software I make will explore all the facets of an idea, and I try to stuff in as many features as I can. Shrub is different, because “Apps” are all about reduction. It’s a “do one thing, and do it well” mode of thinking.

Jeffrey Alan Scudder and Linked by Air, Shrub, 2014.

SK: Your works often relate back to play and games. Making a drawing can be seen as an act of playing a non-competitive game like catch or patty cake. Some works use the controllers for various consoles, like PlayStation. What's interesting to you about the idea of games? How do you see your work as a way of playing?

JAS: I’m mainly interested in video games as they relate to the process of changing an image while viewing it. If you're playing a Mario game, you can make Mario move left and right with your controller; you can jump on mushrooms and do all the normal Mario things. If thought of as an image editor, Mario is very limited. One could use Microsoft Paint to make the same images that Mario generates, but it would take much longer to plot all those pixels. Like Mario, I try to create tools for making certain kinds of images in certain kinds of ways, which often makes them fun and playful to use. When I draw marks, I do it playfully.

Explained Pictures with Jeffrey Scudder, The New School, 2016.

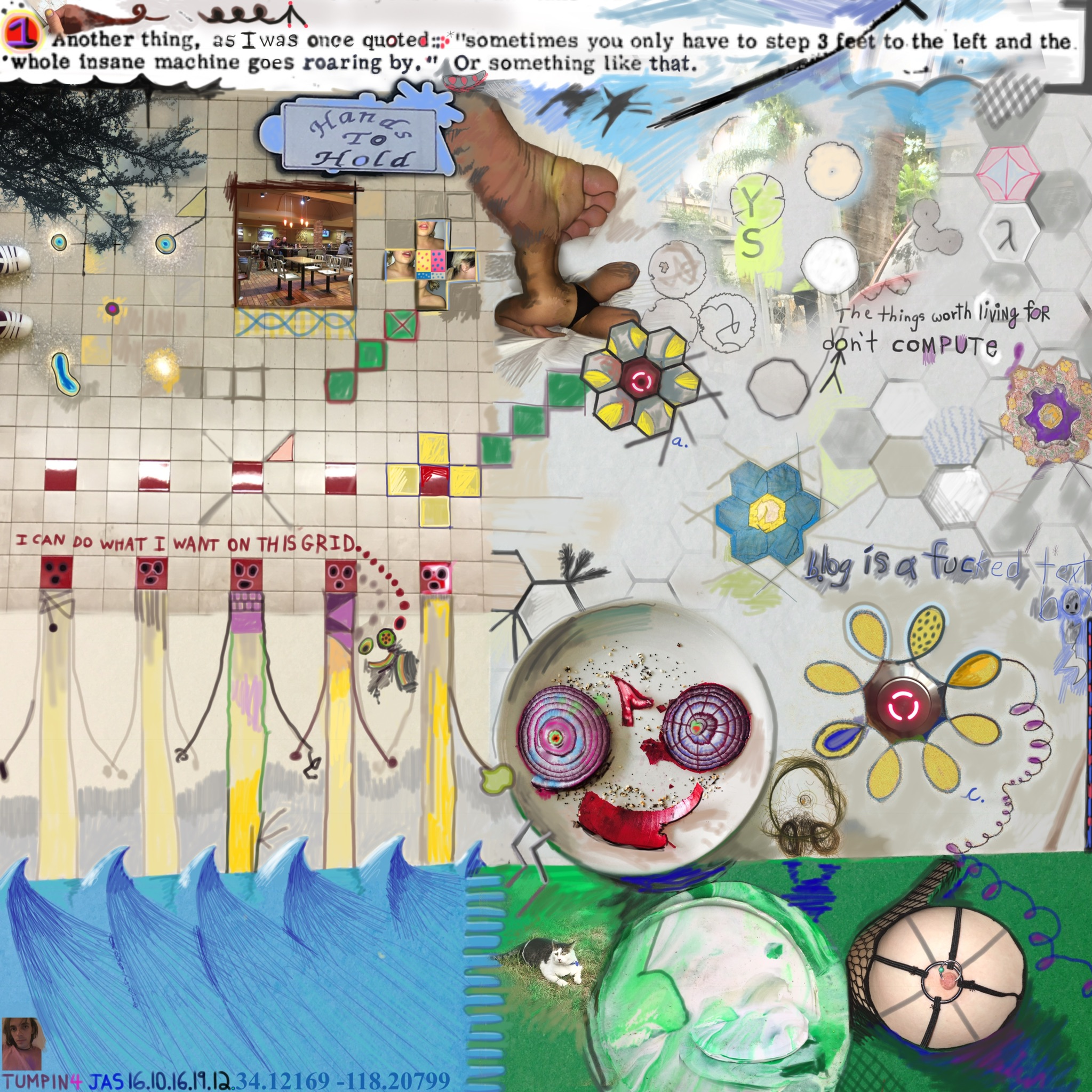

Jeffrey Alan Scudder, 16.10.16.19.12, 2016.

SK: Does a specific work come to mind here?

JAS: Most of my software is designed this way. Media theorist Lev Manovich writes about Photoshop as being like a cathedral where the ultimate goal is to perform every possible function related to still imagery, as they keep tacking on additional features on over the years. The end game for Photoshop is to be able to do everything, regardless of convenience, whereas the endgame for one of my painting tools is to be able to explore certain kinds of image spaces with ease. Finger Quilt is a good example of this.

Finger Quilt iOS App Launch Trailer (Dark Version).

So many of your works also are related in specific ways and seem like they quote from one another. Does that idea resonate with you?

Yes. The tools that I make inspire new kinds of drawing practices in other media. When I draw with pencil, I often think about processes that I've developed on the computer and try to simplify them or represent them. If you build a hammer, then you have a useful tool. If you draw that hammer or give it a name, then you have an idea that begins and ends somewhere. I think quoting something that you've already made is how you begin to create your own language.

I want to ask you about your interest in poetry, and using text as drawing. You draw out letters in messages and insert your own hand into text that is so often standardized in typefaces. How do you see text as part of your drawing practice?

Sometimes in my digital paintings I've used computer generated text, but mostly I prefer writing it out by hand. It goes back to the idea of how you differentiate a drawing or a painting from all the other images out there in the world. Signatures are really cheesy and some claim you're not supposed to put one in the corner of a painting because it makes you seem egotistical. In many ways, it’s a backwards thing to do. Contemporary painters usually obtain attribution in their work via its initial appearance in an exhibition. All the associated metadata surrounding the exhibition is what authenticates the work. Digital painting doesn’t have this as its default mode, and if we want to bypass the exhibition, regardless of media, then we need to resort to less subtle methods of authentication. I do this by inscribing the necessary information directly into the picture.

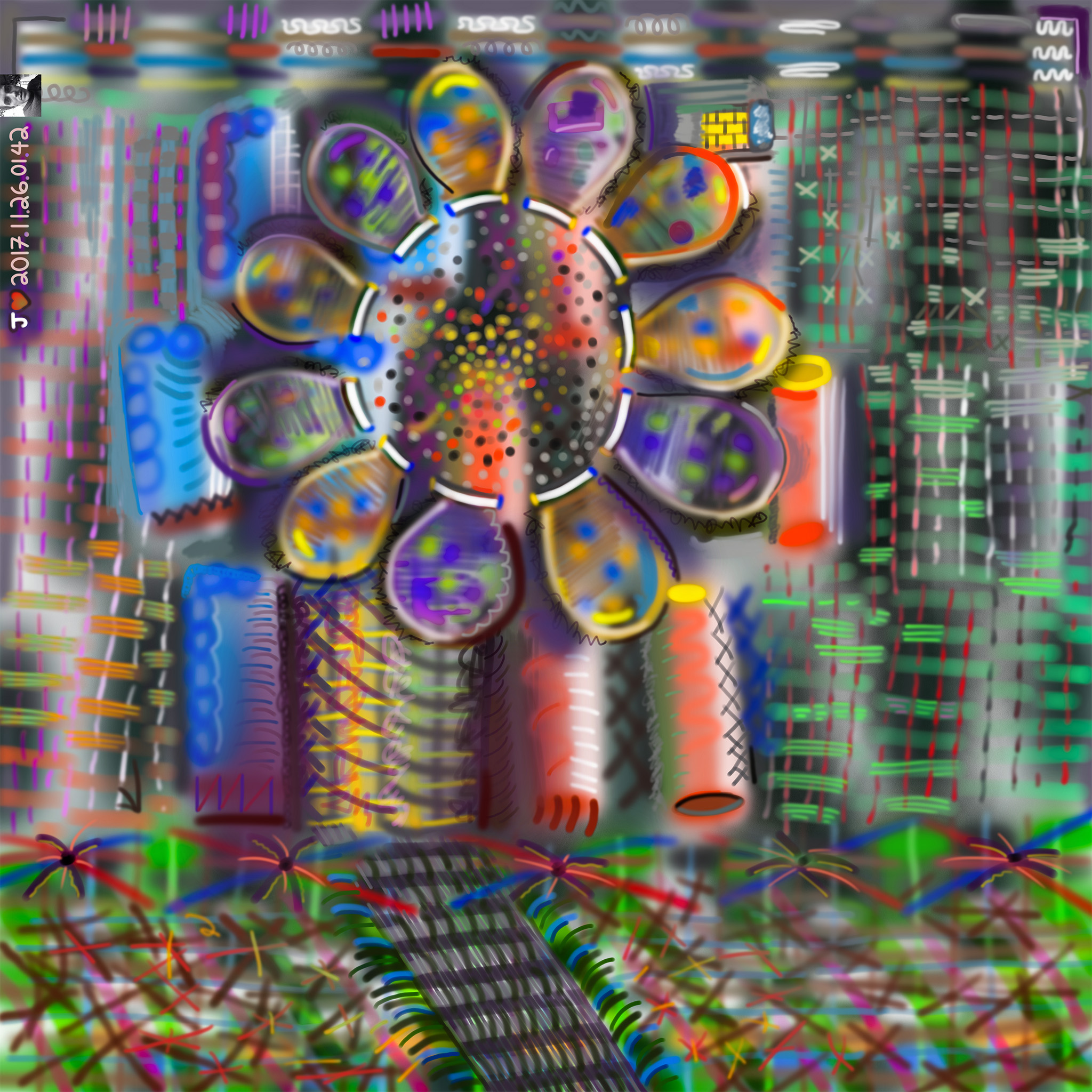

Jeffrey Alan Scudder, 2017.11.26.01.42, 2017.

SK: The signature is a mode of inserting the personal into a space that is so often thought of as anonymous. It also reminds me of the way you put your picture, a photograph of you, on both your websites and in your drawings.

JAS: That's a really good point. It makes things more personal. The goal of my digital paintings is to invite you into my visual line of thought. I sign and date them visibly. In Ten Minute Painting, I write that “A painting is just a kind of picture message.” These days, especially when we see images in all different media, it's important that the digital painting can be recognized easily. I like to think of them as containing all the information needed for you to get into a concentrated mode of viewing.

SK: Many of your pieces also take the notion of chance and circumstance into consideration. How do you work with this idea? What's so exciting about the stochastic for you?

JAS: There's a big history of chance and improvisation in the arts. John Cage once had Merce Cunningham's company flip coins for him while they were sitting around in order to help him score a piece. In computer art, a generative idea is where you set some parameters and then you randomize the variables so that different kinds of results come out and surprise you. Video games usually have this to a certain degree. I did some work for a while where I played multiple copies of the same game simultaneously in order to highlight the stochastic elements.

Kirby's Dreamlaaand – Stage 1 (Gameplay), 2015.

In general, stochastic work has become a bit boring. I think that for a while we all believed that one could generate true novelty, but you can only roll a dice so many times and be surprised at the results. Ten Minute Painting remarks on this: “Like a deck of cards, [this work] is the same no matter how it is shuffled.”

Ten Minute Painting (semver 1.0.0) (iOS 10 Recording) [Ordered Messaging], 2017.

SK: That's nice.

JAS: Yeah. It rearranges itself while showing that it is no big deal to do so. I think that's really interesting because it shows how educated we have become about computers. We have learned the more variability you add to something, the longer it takes before you get bored. Eventually, you are just tired of the whole idea. In video games, we gorge on chance. It’s important to be aware of its eventual banalities. The same thing happens when you look at the latest neural network-generated images and “artificial intelligence” art.

Let’s examine Google’s DeepDream. It's really cool when you first see the effect, but very quickly it becomes so unsurprising. What’s interesting is the process, not the results. But the process isn’t even that complicated. It just requires lots of data. I always found that what’s most interesting about dice is who rolls them, and for what reason? The artist, the dungeon master, Google, a lunatic playing Russian Roulette with a revolver: all employ chance differently. Context in relationship to chance is the most important thing.

SK: This reminds me of Chatroulette, which seemed infinite. I could look at it for a full half hour and there were enough people to see. I never ran out of people.

JAS: But eventually you stopped looking at it, never to return, right? I'm interested in developing things that I can continuously be involved with.

My mother Tricia is a quilter and she is a member of a guild that meets up every week to talk and work collaboratively. It's a really big part of her life. I think artists have historically been pretty good at defining their own values, yet not many people I know are really doing that in the art world today. I see artists are behaving a lot more like silos, especially as their careers take off. I think that it'd be cool to have more scenes, more spirituality, more disparate value systems and modes of presentation.

SK: The way you talk about performance reminds me of the way that music is performative or collaborative. Your drawing tools like the Dot tool have an instrument-like quality to them. Do you think of your engagement with performance as musical?

JAS: Definitely. I think my performances are musical in the sense that I divide and organize space and time while playing with my inventions. Certain strains of modern and contemporary composition interest me and I’m especially inspired by the work of Goodiepal, a Danish computer musician whose band GP&PLS I spent the better part of this past summer travelling and performing with in Europe. I have also invented an instrument for live sound manipulation, called Cricket.

Cricket Tutorial, 2017.

SK: What have you been up to lately?

.jpg)

JAS Team at Harvard (Julia Yerger, Artur Erman, Jeffrey Heart).

JAS: Along with some friends I’ve recently formed a digital painting team called Just Another System. I've been modifying some of my drawing tools and instruments to be better used by my teammates, and making some new ones as well. Rather than focusing on just my needs, or those of an anonymous user base, I’m now concentrated on providing tools for specific individuals in a group dynamic. We just finished our first tour in the northeast where we did 10 events and presented at several schools: Parsons, Rutgers, RISD, UMASS, Harvard, Temple University, and Yale in that order. The team consists of myself, Julia Yerger, Artur Erman, and Mark Fingerhut with musical guest Chase Underwood Ceglie. We had so much fun!

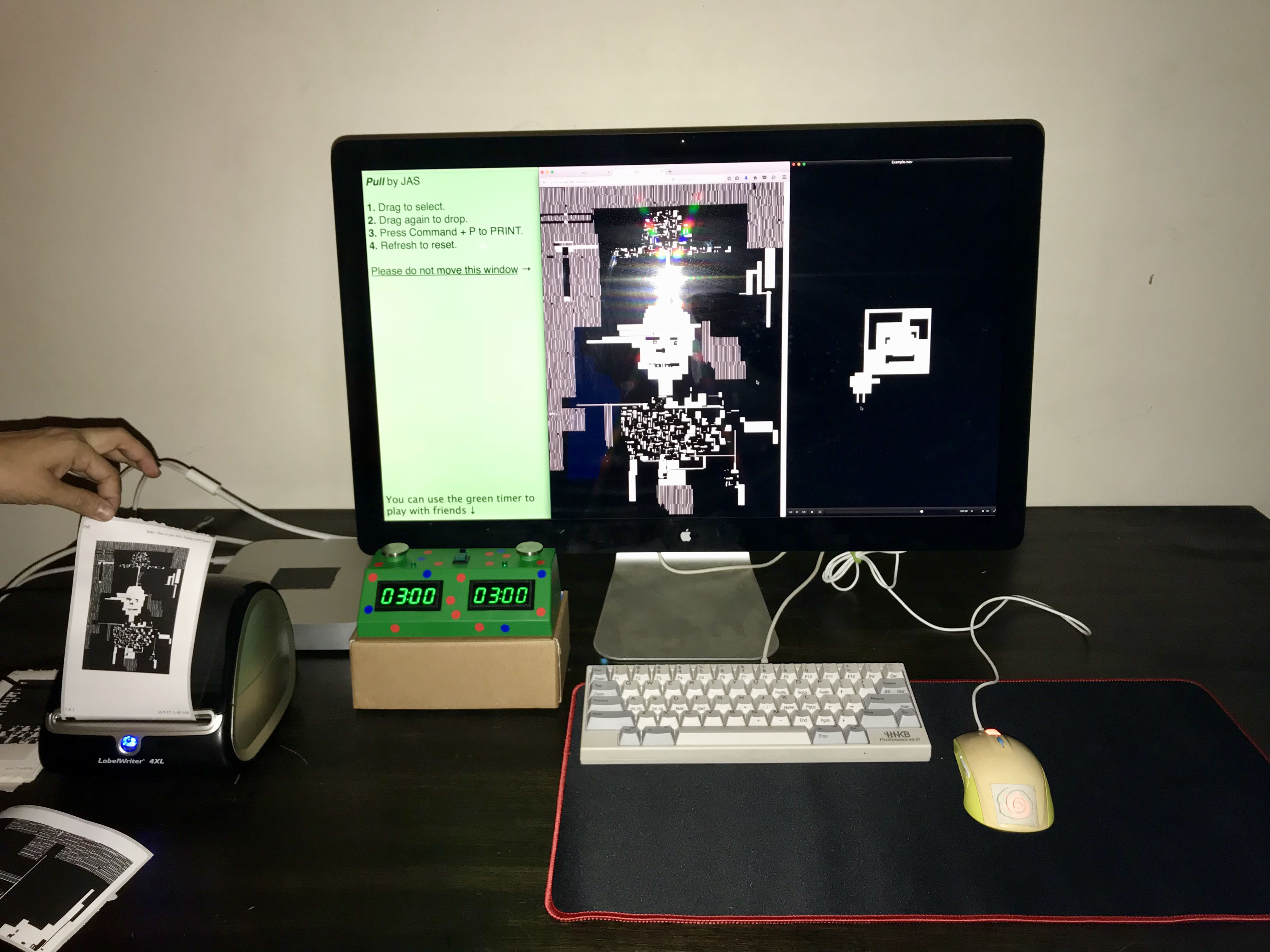

Just Another System's RDP @ Parson's School of Design: November 2nd, 2017.

JAS Cricket Karaoke & Pull Workshop at Victoria Sobel's.

.jpg)

JAS Team at RISD (Julia Yerger).