This essay accompanies the presentation of Rent-a-Negro as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

“I remember years ago… when I would go to a party and I’d be the only colored brother there. And then I’d go to another party, and I’d be the only colored brother there… So now I recognized that there was a prime need to be filled here. So I started my famous Cambridge Rent-a-Negro plan.” - Godfrey Cambridge, 1964

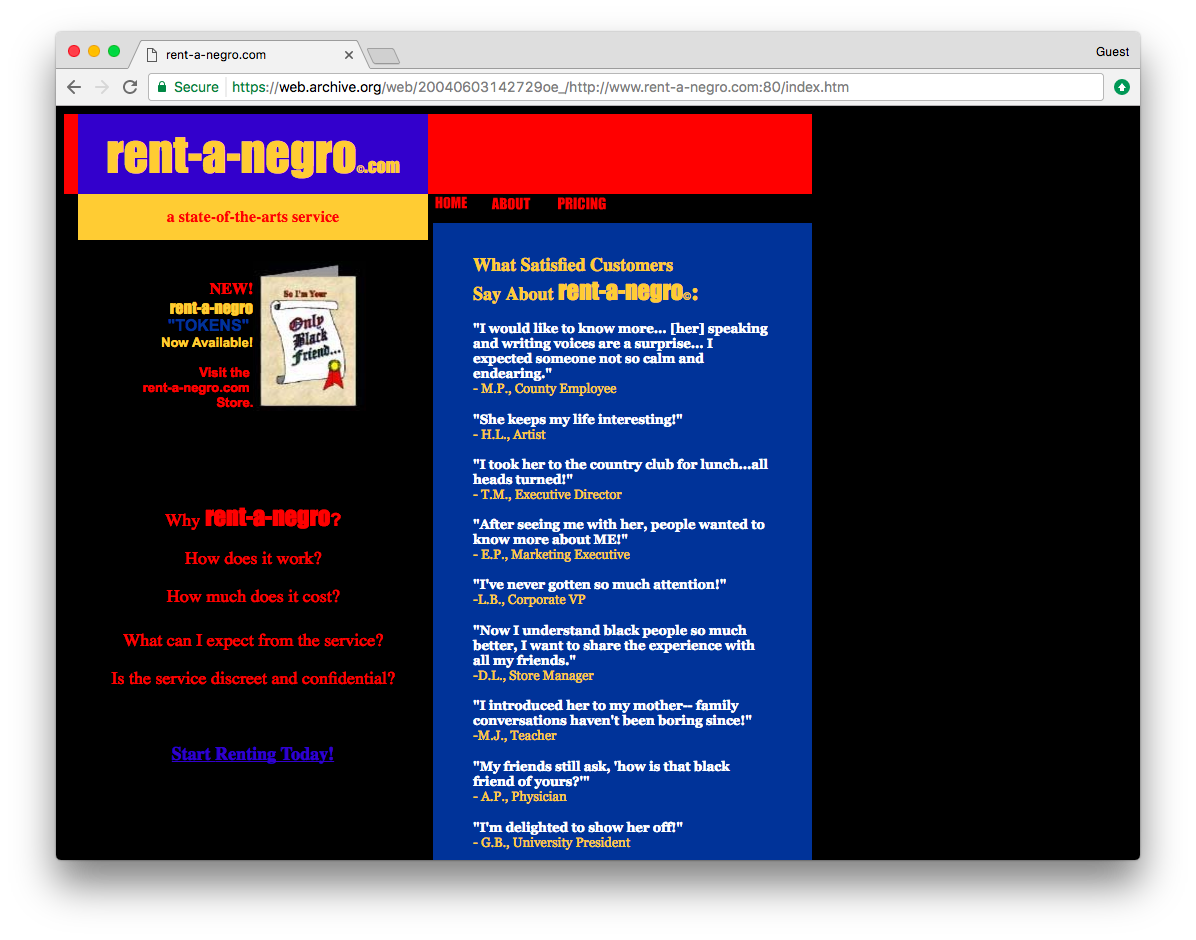

Having lived in Portland, Oregon since 1997 and exhausted by its white liberal smarminess, in April 2003 conceptual artist damali ayo brought comic and actor Godfrey Cambridge’s concept of ‘rent-a-negro’ to the digital sphere. Online until 2012, her satirical website rent-a-negro.com offered her services as a Black woman with decades of experience to individuals, nonprofits, and corporations who sought to prove their diversity credentials, enliven their pale gatherings, and expose themselves to another culture. The site consisted of wry advertorial web copy, testimonials, pricing for services, and a rental request web form, complete with credit card icons indicating accepted payment methods. Encompassing digital performance, print publication, and public engagement, rent-a-negro.com is a canonical piece of net art, Black art, and ‘art art,’ and deserves a reconsideration in light of today’s extensive commodification of Blackness, identity discourse, and reparations concepts.

When you can’t buy, you rent. The relegation of slavery to the penal system forced whites of all classes to develop socially and legally feasible means of continuing to extract labor, feeling, flesh, style, and whatever else they wanted from Black people in civil society both online and offline. The foundational expectation of free labor from and total access to Black people would not change just because of the Thirteenth Amendment; as Greg Tate puts it, Black people “continue to find ourselves being sold as hunted outsiders and privileged insiders in the same breath. In a world where we're seen as both the most loathed and the most alluring of creatures we are still the most co-optable and the most erasable of beings too.” Black subjugation and Black success both operate along the principles Tate describes. The concept of “renting” serves to encompass these post-slavery tactics both macro and micro, as well as the way that “we continue to look at Black people in a service mentality,” as ayo states in a 2005 interview.

The About page of rent-a-negro.com states: “As times have changed the need for black people in your life has changed but not diminished.” At every turn, Black folks are forced to navigate the labyrinth of whiteness, in which it is generally unsafe not to comply with expectations of service. As such, many interactions feel like and are work, and the ostensible paradigm shift of Emancipation only reveals continuity with older forms of subjugation. Black people are expected to feel appreciative of selective, tokenized inclusion in white institutions and circles, all the while knowing we are only put there to titillate them and legitimize their dependence on the continuing exploitation and destruction of Black life. rent-a-negro.com imagines a world where these encounters and expectations of service are paid, and thus recognized as the labor they are.

Screenshot of rent-a-negro.com (2003) via Wayback Machine. Archived June 3, 2004.

Maintaining the site itself was an intensive and invasive labor. While presumably some visitors understood the satire, many clearly did not, and ayo received many rental requests, ranging from requests to attend a bridge club to requests for lynchings. She never accepted any of the rental requests, though she responded to a number of emails. Things got out of control quickly; according to Wikipedia, the work received over 400,000 hits in its first month. Eventually ayo realized she wouldn’t be able to deal with the volume of rental request forms and emails she was receiving. Initially, the rental request form stated that the site would respond in 2-3 weeks; however, in a 2005 reading at Karibu books broadcast on CSPAN2 Book TV, ayo states that she received so many rental requests that she eventually modified the web form to respond to requests with: “I’m sorry, our records show that you still have outstanding rental debt with other Black people in your community, and your request has been denied.”

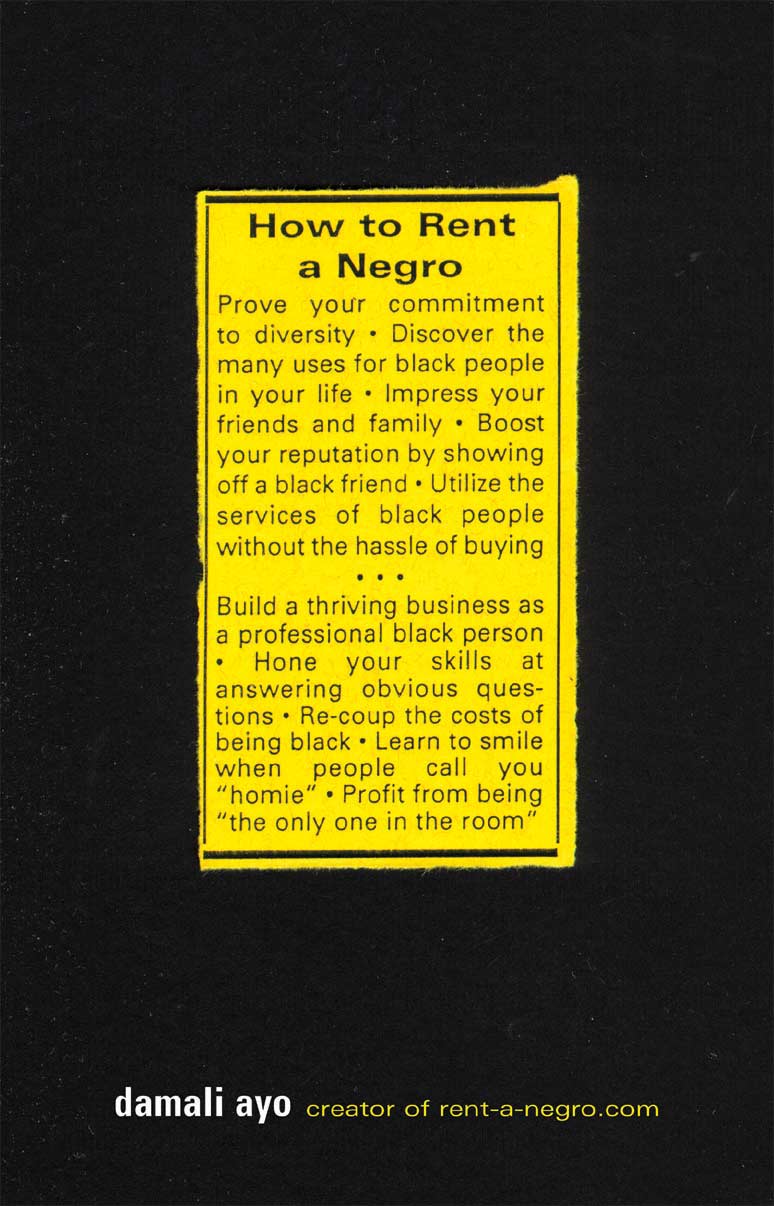

In 2005, ayo published How to Rent a Negro with Lawrence Hill Books, which serves as a kind of DIY guide. In the same Book TV interview, ayo states that she began writing the book after receiving resumes and cover letters from many Black folks looking to work for the site. Taking on the infotainment format of many early 21st century sites-turned-books, the first half of the text addresses renters, while the latter half addresses rentals. In a writing style and tone that elaborates on the advertorial web copy of rent-a-negro.com, the book provides tips and tricks, real-world examples, sample invoices, sample rental request forms, email exchanges, and more. She also seems to draw from her own personal experiences of ‘being a rental’ in some of the narrative portions of the text, such as a story in the “Stories from the Field” section from grade school where she and a white boy received the highest scores on a quiz in class. She was subsequently punished for her success and pitted against the boy, and states: “No one told me this was a rental and that they wanted me to fail. If I was supposed to get a bad score I would have answered the questions wrong.”

Image courtesy damali ayo and Lawrence Hill Books.

While print publication ended the feedback loop engendered by website’s rental request forms, printing some of these forms, email exchanges, and other such material allowed ayo to show proof of the audience’s complicity in the process of anti-Black objectification. This subsumption of audience response into an aspect of the work itself is in line with ayo’s practice more generally, as performance theorist Brandi Wilkins Catanese argues. She points to ayo’s 2001 work ontology, in which a found pair of racist ‘mammy and uncle’ salt and pepper shakers discuss ayo's work. The male shaker says, "her fundamental conceptual strategy is to implicate the spectator as complicit — not only in the society manufacturing such constructs, but in the art itself as audience is unwittingly transformed into medium.” For Catanese, this transformational feedback loop is present in ayo’s site, “as the act of completing the rental form makes site visitors' subjectivity a part of rent-a-negro.com itself.” The abusive exchanges ayo suffered in maintaining the website are also part of the work, and exposing them adds to its meaning. They point to how maintaining the site itself and interacting with people was a kind of rental work.

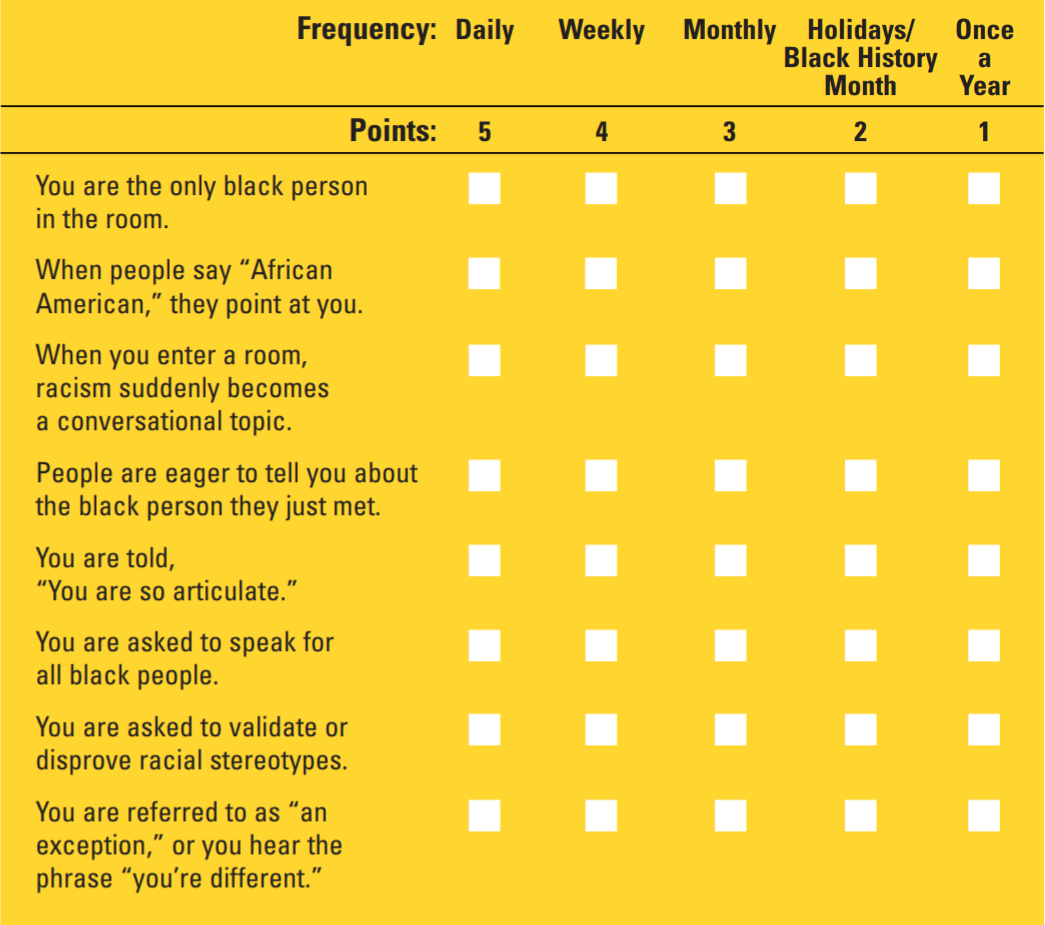

To repeat: renting is not new at all. It simply often goes unrecognized as such. As ayo writes in the book’s intro, “the practice of renting has been a long-standing tradition since the end of the days of purchase. Renting takes place on a daily basis, virtually at any time, in nearly any location. Unfortunately much of this renting has occurred without the consent or compensation of those being rented.” Encounters where non-Black people violate our physical and emotional boundaries, expect us to be encyclopedic or represent the entire race, and push for us to legitimize whiteness all rack up the bill; naturally, what comes at a psychic cost can also be conceptualized as warranting payment. This moment of realization may be a useful means of recalibrating one’s relationships, as well as realizing more generally that almost no aspect of human relationships exists outside of the cash nexus. Indeed, later in the book, she advises ‘newly-minted rent-a-negroes’ to “make a list of the people you’ve already worked for. Your first step may to be to issue a series of retroactive bills.”

Excerpt of a quiz from ayo’s book How to Rent a Negro, from a section titled “How Can I Tell if I’m Being Rented?”

The conceptual and political position in which draining interracial encounters demand a wage is redolent of Federici’s arguments in Wages Against Housework (1975). She cautions us not to see the argument for waging housework as a lump of money: “The problem with this position is that in our imagination we usually add a bit of money to the shitty lives we have now and then ask, so what?” Instead, the position of seeing this activity as worthy of pay demystifies the wage, reveals its violent relegation of women to a second class: “It is the demand by which our nature ends and our struggle begins because just to want wages for housework means to refuse that work as the expression of our nature.” There are theoretical parallels here with rent-a-negro, which could aso potentially fall victim to a reductive ‘lump of money’ reading. The problem is that anti-Blackness needs to end, and paying Black people to suffer it while letting it continue is not any kind of solution. As Brandi Wilkins Catanese asks, is such behavior really “any less offensive when the objectification that they inflict upon black subjects is coupled with remuneration?” In opposition to this reductive reading, the conceptual and political position of wages for Blackness allows for a refusal to accept the foundational American premise that constant service is an expression of the nature of Blackness.

Indeed, to me there is a deeper level to ayo’s piece about the commodification of identity and the reductive reading of reparations as simply creating the conditions for Black folks to individually lean in to settler colonial capitalism, to reclaim the piece of the American imperial pie that is owed due to the Middle Passage. In ayo’s framework, this kind of selective, tokenizing inclusion is only more rental of Black people. The process by which some set of activities moves from being seen as natural to a class of people, to being seen as work warranting a wage, should not be confused for reparations. It is subsumption into capitalism, in this case to a particular kind of color-blind market objectivism. ayo satirizes this in the intro to her book: “Strained dynamics have plagued race relations for centuries. What better way to alleviate this tension and move into the future than with honest negotiation of fees for services rendered? Let’s talk business. It’s the American way.”

Image courtesy damali ayo.

We should avoid a reductive reading of the work and concept. The point is not to wage experiences of anti-Blackness and keep up business as usual, but to eradicate it entirely. As ayo states regarding her use of the anachronistic pejorative in the work’s title: “I use the word ‘Negro’ very deliberately, and that's because the kind of behaviors that we're talking about happening... should be as outdated as the word ‘Negro.’” Fourteen years later, violations of Black boundaries and expectations of Black service are still constant, both online and off. ePay developments, the rise of social media, and constant digital blackface cast ayo’s work in a new light. The site’s early rejection of utopian post-identity visions of cyberspace rings truer than ever in a contemporary digital landscape where Black women experience daily harassment mirroring the physical world. And In 2017, ayo’s concept has been somewhat normalized: many Black people post ePay links on social media, in an attempt to reclaim their digital time.

Just as we should avoid being reductive, we should also recognize that taking the concept literally without committing to the ‘lump of money’ reading is possible, and in fact good. White people should be paying Black people for their emotional labor and realizing how much ‘rental’ they enact on them. For example, literally right now you could click any of the ePay links included in Brooklyn artist Winslow Laroche’s ongoing work list of Black people 2 donate 2 (2016). This kind of payment is not supposed to replace reparations or end anti-Blackness; it’s baby steps toward repair, a gesture of acknowledgement. In giving viewers the choice to take the concept literally or not, and in subsuming audience response into the work itself, ayo’s piece operates on multiple levels along with being a satirical mirror to society: it not only encourages a recalibration of interracial dynamics, but can also serve as a kind of introduction to a larger conversation about what the healing process looks like for a country built on the destruction of native and Black life and bent on protecting stolen resources it claims as its own. If whites start by giving away their generational wealth and access, a path can potentially open to the conceptual position — when one considers existing while Black as worthy of a wage, one can begin to reject the anti-Black expectation of service that is treated as a natural property of Blackness.