On April 22, 2017, Rhizome’s ninth edition of the Seven on Seven conference took place at the New Museum’s theater. Each year, Seven on Seven pairs seven artists and seven technologists and asks them to create something new: a prototype, an artwork, an app, or whatever they imagine. This year, the resulting projects ranged from an app for safer sexting to a CMS for one to Tinder for policy decisions. More details below.

Keynote: Doreen St. Félix

On the internet, it's harder to be a dog than you might think

Seven on Seven’s keynote speaker, Doreen St. Félix, opened the event by wading into ongoing debates about online cultural appropriation.

In the ’90s, she argued, the text-centric internet seemed to offer the promise that anyone could synthesize a new identity, unfettered by appearance or skin color, but in recent years, social media identity has been increasingly tied to legal names and photographic documentation.

Alongside this, users are increasingly caught up in arguments about cultural ownership. Communities—especially black communities—develop their own online cultures and vernaculars, and find their work appropriated and capitalized on by other users, artists, and corporations. St. Félix wrote about this phenomenon with regards to the now-shuttered app Vine in her 2015 article, “Black Teens are Breaking the Internet and Seeing None of the Profits.” Meanwhile, right-wing users are making efforts to appropriate black identity wholesale in order to infiltrate and upend the Black Lives Matter movement.

In her keynote, though, St. Félix argued for a moderate position with regard to cultural ownership. Yes, others capitalize on black identity, she argued, but in many cases, what is taken is less valuable than what remains. St. Felix offered that blackness is, at least in part, defined by its fugitivity. The collective historical and lifelong embodied knowledge that black users carry with them is what informs and undergirds every aspect of their online culture, and this cannot be appropriated.

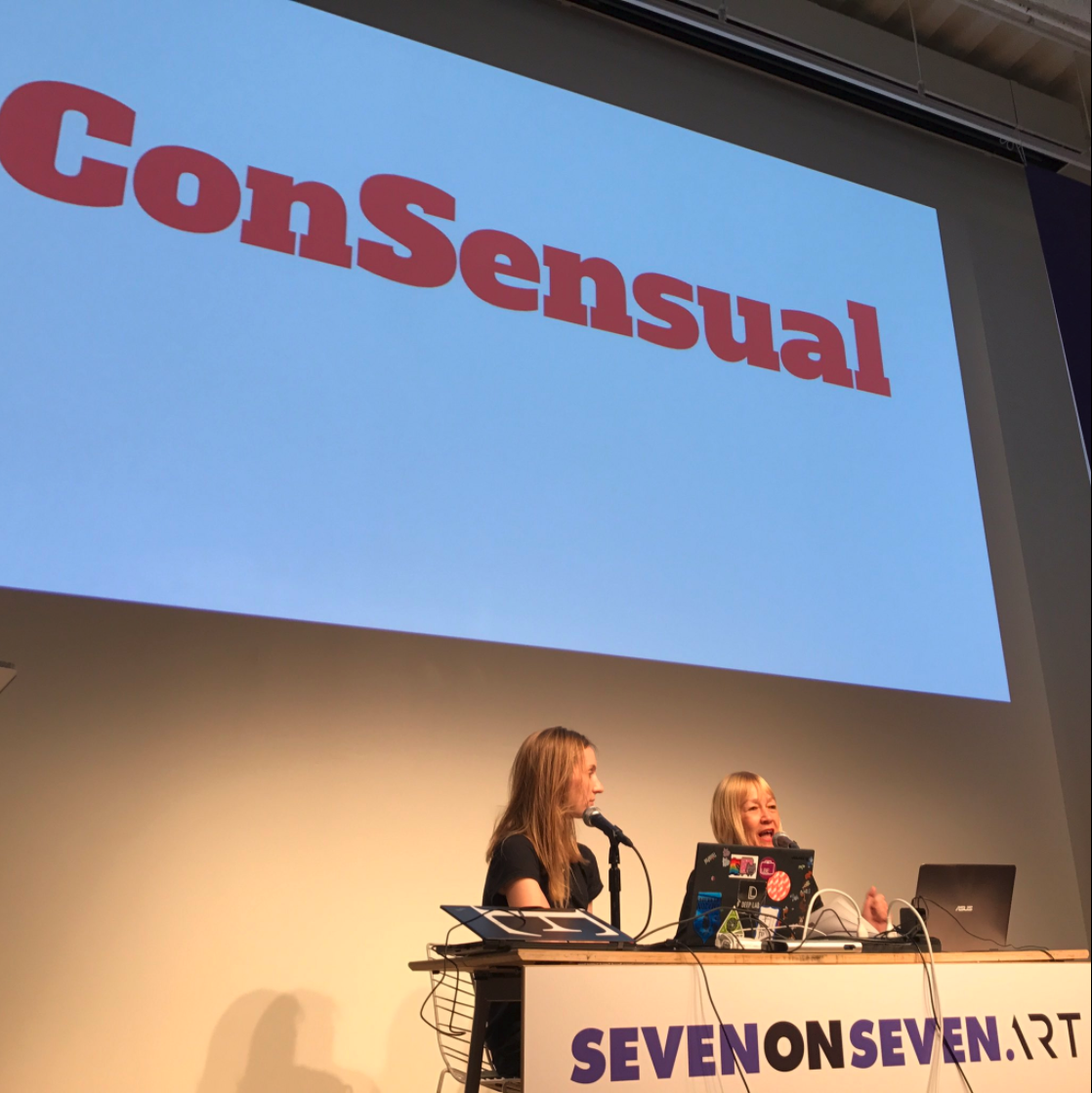

Pair One: Addie Wagenknecht & Cindy Gallop

This world is not designed with sex in mind (but it should be)

Credit: @lizsayz

Addie Wagenknecht and Cindy Gallop found common purpose in the idea that very few of the products we use are designed with sex in mind. “All around the world,” Gallop noted in an interview before the event, “a lot of people are having a lot of sex in a lot of cars. And yet the automotive industry is spectacularly failing to factor this into their product design, dealerships, CRM, advertising.” This isn't mere oversight. Apple’s App Store, for example, demands that products downplay their sexual uses. And the result is more awkwardness and risk for users. “When you don't admit it goes on,” Gallop noted during the event, “you don't design for it, you don't make it safe.”

The duo proposed an app called ConSensual, a tool designed to facilitate safer, more fulfilling online sexual communication. They worked with four volunteers—Susana Aho, Chris Fiore, Anna Kryukova, and Cybele Grandjean—to conceptualize it, and they’re actively working to make it a reality.

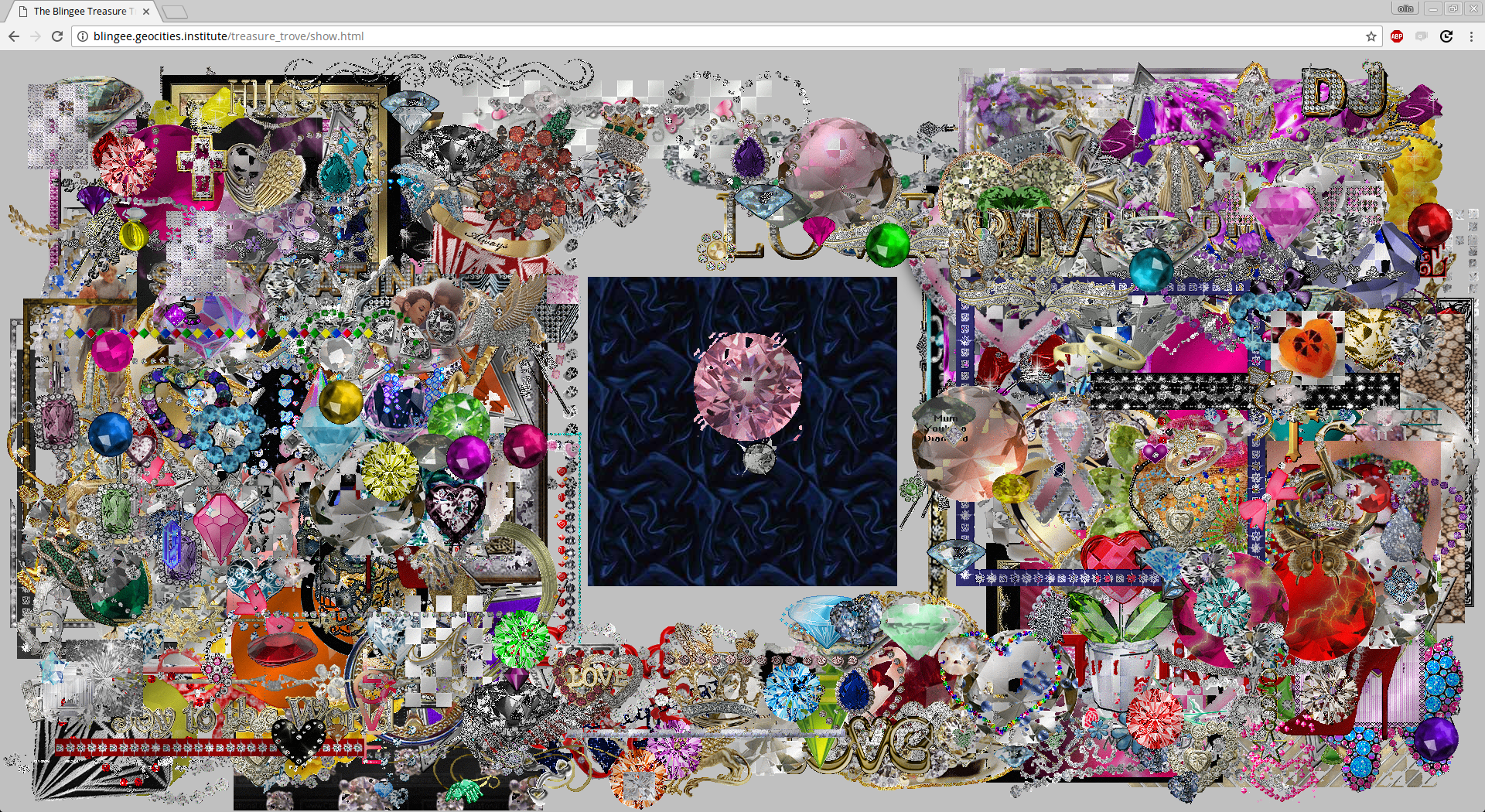

Pair Two: Olia Lialina & Mike Tyka

The Blingeeverse is a cruel and wondrous place

Olia Lialina opened her presentation with Mike Tyka by taking me to task for my use of the word “technology.” “Every time you use the word ‘technology,’ a child is born who will not know the difference between hardware and software.” The word is a black box, and disempowers us from understanding the more concrete aspects of the way our world is run.

But! I get to have the last word, and I would argue that “technology”—while bad for talking about computers and networks and platforms and other aspects of the technical apparatus that surrounds us—is actually pretty useful for describing a field, a social and institutional arena in which people compete for various kinds of capital. How do you like them apples?

Lialina and Tyka chose the social network Blingee, which allows users to create collaged compositions made up of animated stamps, as their subject matter. Lialina and Tyka first created a tool to automate the process of surfing through Blingee by seeing which compositions share particular kinds of stamps; one version of this tool centers Lialina’s favorite Blingee user, Irina Vladimirovna Kuleshova, while another version moves more freely through the network, including compositions that are less appealing to Lialina's discerning eye.

Then, Tyka began to explore political speech on Blingee, which includes the extremist positions now familiar to any internet user. He used machine learning to create a tool to automate the blingee creation process, and loaded them into a Captcha quiz to see whether the audience could prove their human-ness by identifying works made by humans and those made by bots. (We failed.) Tyka’s success seemed only to bring him worry, and he expressed concern about how easy it was to automate plausible cultural production—a point that seemed to directly contradict St. Félix’s keynote argument.

Finally, as their last gesture, Lialina and Tyka tackled the problem of freeing the Blingee gifs from the Blingee platform, which are kept under lock and key by the platform. They managed to harvest 440 jewel animations, which Lialina collaged together in what must surely be one of the world’s most beautiful web pages.

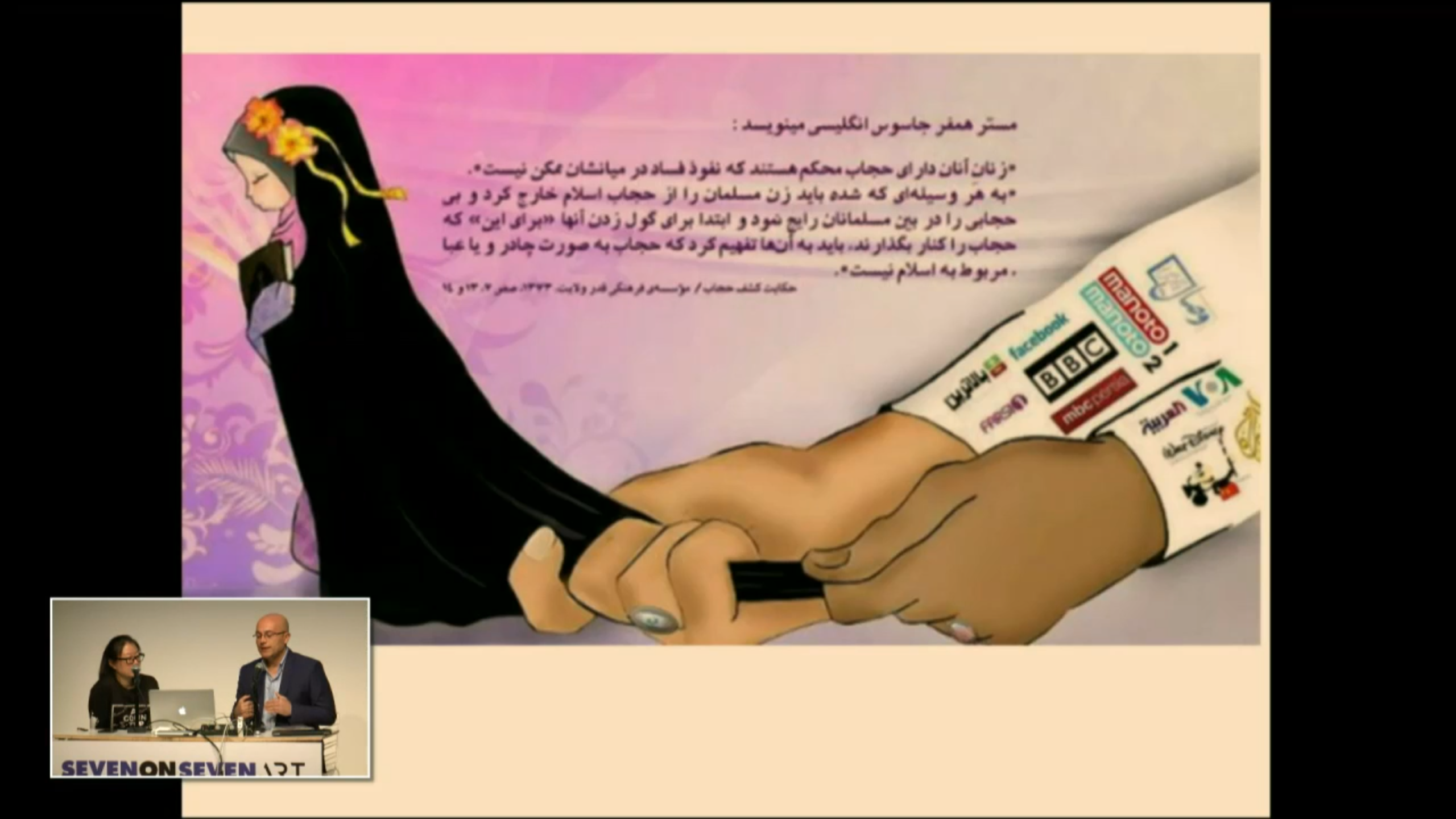

Pair Three: Miao Ying & Mehdi Yahyanejad

Censorship is more about inconvenience than fear

Miao Ying and Mehdi Yahyanejad found common ground in their personal experiences of growing up under censorship, sharing stories of internet communication in China and Iran.

For Miao, internet censorship was a research topic and a source of fascination. One early project, which took place when Google was still available in China, involved searching for every term in a dictionary, and erasing (by hand) those which were blocked. Later, as smartphones became ubiquitous, she cultivated an appreciation for the forms of communication that evolved as a means of evading censorship, such as using images of sound-alike terms to communicated forbidden concepts.

Nevertheless, censorship has profound effects. “The editing of the memory is always involved. You don't remember things as they actually happened.”

Yahyanejad’s experience of censorship came through his experience as founder of Balatarin, a site similar to Reddit that has widespread use in Iran. When the Iranian Ministry of Communication censored the platform, he asked users to telephone them directly and register their protest. Later, as harassment grew more common on the platform, he implemented some basic standards to protect vulnerable users. These experience led to him being portrayed in political cartoons alternately as a champion and an enemy of free speech.

For their collaboration, Miao and Yahyanejad looked to the internet of 2017, suggesting that the “filter bubble” created by the modern internet serves as a kind of soft censorship, invisibly editing out information that is deemed unpleasant or irrelevant. They proposed a “filter bubble detox” as a way of addressing this kind of censorship and ensuring a balanced information diet.

Pair Four: DIS & Rachel Haot

Public policy should be more like hooking up

“How can we convert Tinder users into active voters?”

Rachel Haot, formerly Chief Digital Officer of the city of New York and current Managing Director at 1776, set out the stakes of her collaboration with Lauren Boyle and Marco Roso of DIS in these terms. Looking at the state of political communication today, she and DIS concluded that there was an enormous gulf between even the most accessible policy papers and the kinds of online communication to which users are accustomed. Public policy communication should be more like this, Roso proposed, showing a slide of a Buzzfeed quiz titled “What kind of pasta are you?”

Working with designer Pat Shiu and researcher Ethan Chiel, the collaborators created Polimbo, a new app that lets you swipe your way out of public policy limbo. The app offers users a series of scenarios, to which they must respond with a smiley or frowny face.

The app took on the topic of net neutrality, offering glimpses of possible future such as:

“Virtual Reality Pre-K is available at no cost, starting at 18 months.”

“Broadband Basic, the new, free, tiered broadband service reaches 100% accessibility across the US, bridging the digital divide.”

Based on their responses, the app tells users where they come down on the question of net neutrality, and “matches” them with correlated politicians. While the project offered plenty of dystopian absurdity, it also gave the audience a visceral glimpse into the real-world outcomes of present-day policy decisions.

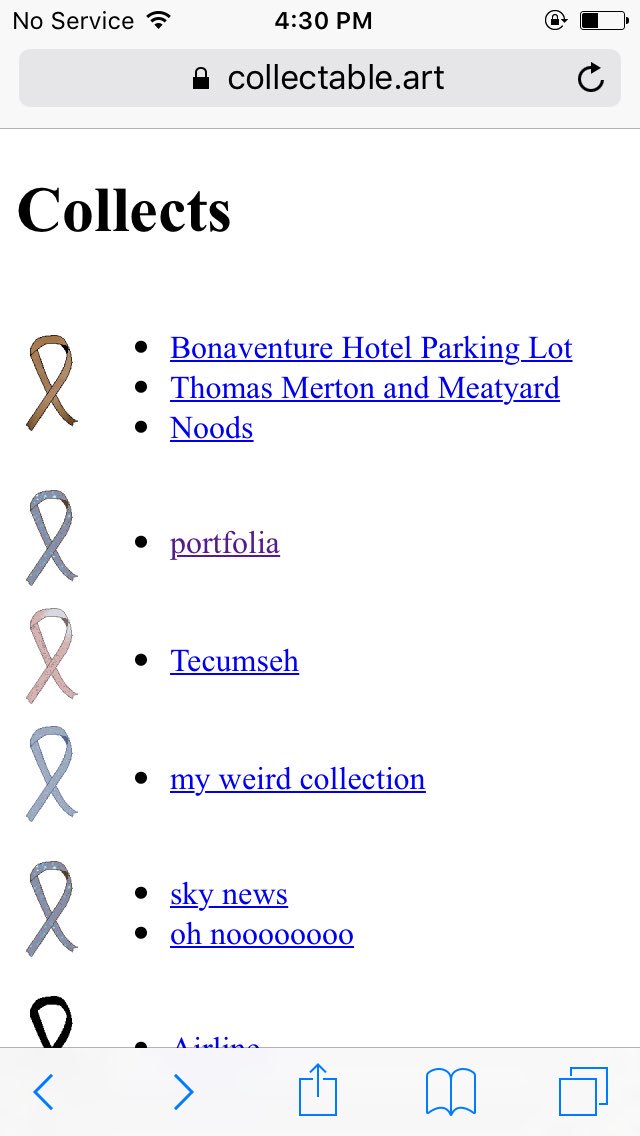

Pair Five: Bunny Rogers & Nozlee Samadzadeh

A CMS for One

Bunny Rogers’s home page, meryn.ru, opens out into an universe of HTML collections: images of ribbons and graves in the shapes of lambs arranged against prison grey backdrops. Nozlee Samadzadeh, who works as an engineer for Vox and is responsible for a content management system (CMS) used by thousands, wondered what it would be like to create a CMS for one. The two collaborated on collectable.art, “a social network in the style of Bunny Rogers,” which is forthcoming as an iOS app.

The app allows users to create their own web collections, featuring images and short captions, All the content on collectables.art is anonymous, all the icons are varying shades of grey, and the only font is Times New Roman. All this may be most suited to Bunny Rogers, but I am not Bunny Rogers, and I found it surprisingly fun and easy to use.

What many will remember from this presentation, though, was the rapport the two developed. They told of their shared interests (Neopets, pixelated dress-up dolls, making clothes) and recounted their failed ideas (a website for Rogers’s ex-boyfriend, a commercial-friendly makeover of Rogers’s online portfolio), and somehow brought the audience along on their journey.

Pair Six: Jayson Musson & Jonah Peretti

“To lose the scroll is to lose your soul.”

Jayson Musson presented his collaboration with Jonah Peretti via a video address, in which he appeared in character as a CEO. A social network called “Blockedt,” it offered users the reassuring experience of constant scrolling without the intrusion of any other visible users. “Keep the phone, and lose the people,” Musson suggested.

Musson did a very good job sending up the character of the CEO, a point that wasn’t lost on Peretti. There was a point in the process, he noted, where he realized that the whole thing was just making fun of startup CEOs like him.

Although the Blockedt app wasn’t ready to ship by the time of Seven on Seven, it had been partly implemented by Sarah Meyer and Manuel Palou of Buzzfeed, and a native web version of this useless app (I’m told mobile web is the future) can be tested here.

It works best on mobile.

Pair Seven: Constant Dullaart & Chris Paik

“Once you have your message, we will help you weaponize it.”

“How easy is it to get someone to say something you want them to say online?,” Thrive's Chris Paik asked during his presentation with artist Constant Dullaart. The two began with an open and honest airing of views about Facebook (“It’s bad, and you shouldn't be on it”—Dullaart; “a wonderful company from a venture capital perspective!”—Paik) before sharing a key stat from a recent Facebook earnings call: the dollar value of each US user of Facebook is many times higher than users from “the rest of the world.” To Dullaart, this suggested that US-based users, because they are more valuable, are therefore more likely to be targets of attempts to control their views and behavior.

Drawing on Paik’s business world connections, the two reached out to firms (whose names they could not disclose, because of aggressive NDAs) to ask about campaigns to sway public opinion online. “Do you want to know what users think?” one firm asked. “Or do you want to make them think something?”

Wondering if this strange apparatus could be used for artistic purposes, to perhaps make its functioning more visible, Dullaart and Paik hired a firm to astroturf the Facebook post for the Seven on Seven event itself. Some users left glowing comments about Rhizome and Seven on Seven ("I believe that this is a good event for both overs of the art and all the people in general.#7on7NYC"). Others criticized it in ways that seemed strangely, unsettlingly plausible ("A privately owned museum, hosting tech giants and venture capital to get cultural validation at 7 on 7.. I dont understand why artists support this... #7on7NYC").

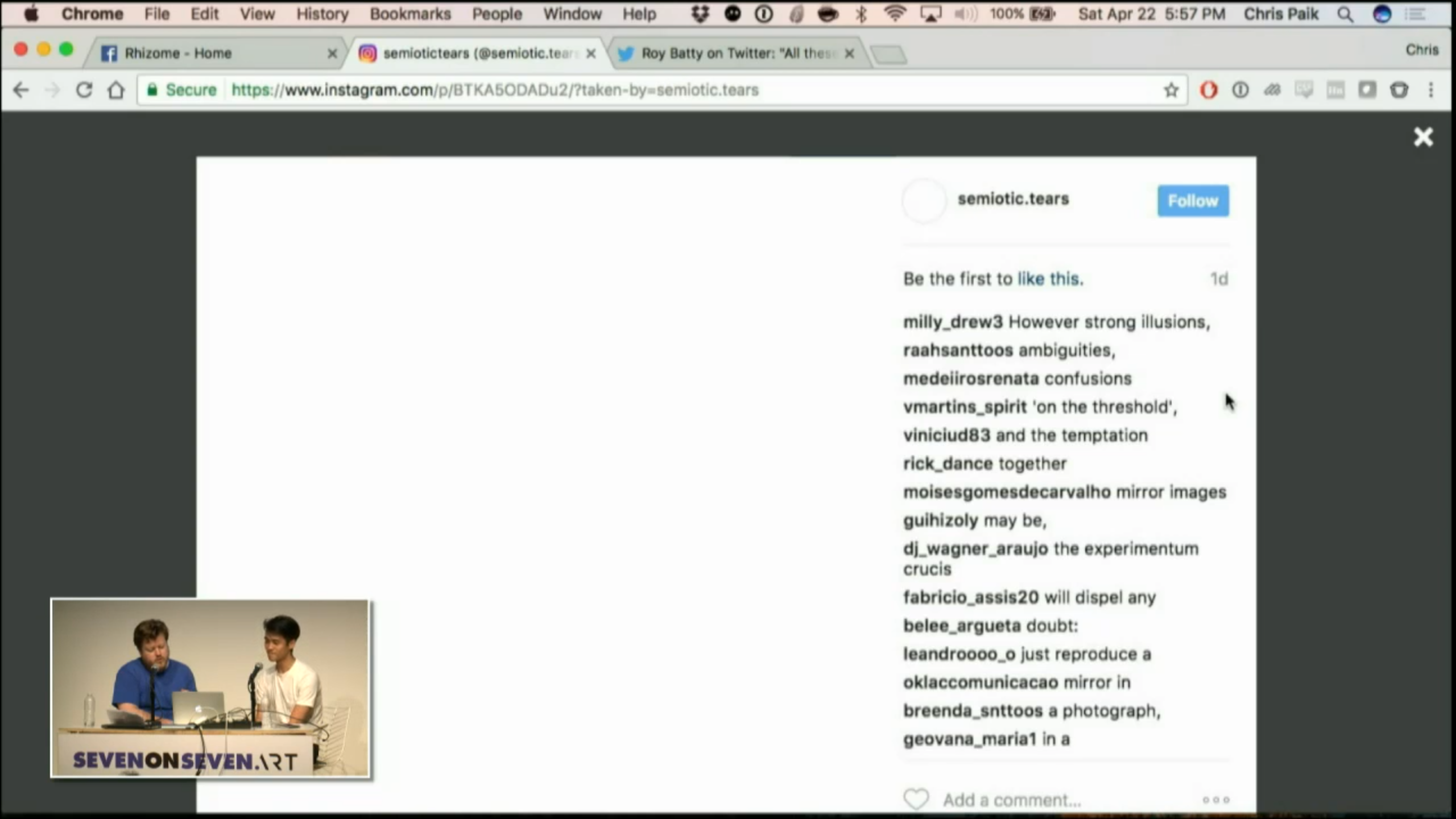

From there, the duo moved on to more poetic applications of their new troll armies. They set up an Instagram account, Semiotic.Tears, and used paid accounts to comment, in sequence, a passage from Umberto Eco’s Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Finally, they set up a Twitter account, @R_O_Y_B_A_T_T_Y, modeled on the eponymous replicant from Blade Runner. The account had published one tweet, and Paik and Dullaart hired tens of thousands of paid Twitter bots to retweet it, spreading it across the Twitterverse.

As their presentation concluded, they brought it up onscreen. “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” They pressed delete, and the audience gasped. And with that, the ninth edition of Seven on Seven came to an end.

SEVEN ON SEVEN 2017