This article accompanies the presentation of Antonio Muntadas's The File Room as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Before entering the The File Room’s online archive of censorship cases, a disclaimer warns visitors that the site “claims no scholarly, editorial or scientific authority…” Making such a disclaimer for an online reference work today seems superfluous, but in 1994, it was crucial for understanding a new kind of information database—one of open-submission and open-access.

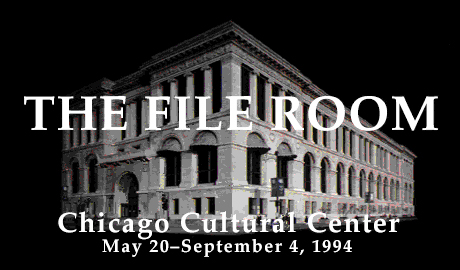

An installation in the form of a database of censorship cases, Antoni Muntadas's The File Room was commissioned and produced by Randolph Street Gallery and staged in 1994 in the galleries of the Chicago Cultural Center and on the then-nascent web. Visitors entered a small, ominous room lined with file cabinets; there, they could approach a computer terminal to browse archives or submit their own accounts of censorship.

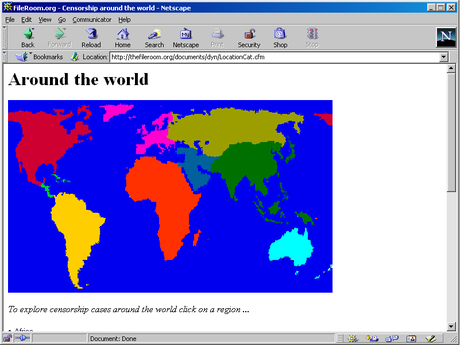

Using a customized, kiosk-mode version of the NCSA Mosaic web browser, they could enter search terms, or sort by category and location. They might encounter stories like case #212, which outlines some of the attacks on artist David Wojnarowicz, whose 1990 exhibition at Illinois State University, "Tongues of Flame," was the subject of a lawsuit from a right wing organization. Or they might find come across case #199, which describes the attempted suppression of What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag? by Dread Scott (1988). The question posed in the title of the work invites visitors to respond, but in order to reply in the notebook provided they must walk across an American flag draped on the floor. Although courts ruled definitively that the work was protected free speech, protests and bomb threats targeted its exhibiting venue, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. A teacher visiting the exhibition was arrested for stepping on the flag, and then-president George Bush described the work as “disgraceful.”1

Record of censorship of work by Dread Scott, included in Antoni Muntadas, The File Room (1994). Courtesy the artist.

They might also choose to write out their own entry, detailing a past incident of censorship. This open-endedness was a crucial aspect of the project. At the time of its launch, researchers with Chicago artist-run space Randolph Street Gallery had written and compiled four hundred documented cases from around the world, many of them submitted by phone, fax, or email. Visitors to the public building where it was staged could also contribute; even today, users on the web can still submit their own entries. “What can be stated and what cannot,” wrote Judith Russi Kirshner at the time, “is always debatable, open to redefinition and potentially infinite.”2 Cataloguing censorship is a project that can never be complete.

Open-submission systems today are often characterized as examples of the utopian, egalitarian ideals of the internet. Wikipedia, for example, as it grows in volume and apparent reliability, reflects a deep structural bias resulting from the sizable racial and gender gaps in their communities of contributors.

When it was created, The File Room faced its own problems of inclusion and access. The internet at that point had only been popularized at the government and university levels, and its access required maneuvering a high barrier of technological savviness.

Perhaps this is why, unlike many of the open-submission databases and encyclopedias that followed it, The File Room is particularly self-critical of its own role in the censorship of information and the limitations of its community of users. It eschewed the quirky coding characteristics that marked many other internet artworks from its era. For example, it differs markedly from the playful user-generated nonsense invited by Douglas Davis’s seminal work The World’s First Collaborative Sentence (1994), which asked users to input their own text in a massive collaborative writing project, open to all comers.

Screenshot from Douglas Davis, The World's First Collaborative Sentence (1994).

Instead, The File Room adopted the ominous aesthetics of bureaucracy, the neutral structure of a detailed database. This allowed for an impressively specific categorization by century, continent, grounds of censorship, and medium. Despite a format that conveys authority, though, the work is no less subjective than The World’s First Collaborative Sentence, or Wikipedia. It is a record of the ideas and concerns of its communities of contributors. "I see the site as a kind of digital artifact of its time," Muntadas notes. "In anthropology, you analyze an object by what elements of its time it accumulated. The File Room accumulated elements of Chicago in 1994 and the state of early web computer graphics."

Early entries in the database do often reflect the concerns of Chicago-based artists in the early 1990s, writing at the tail end of the US culture wars, in which conservatives made concerted efforts to target artists and institutions whose positions challenged their ideas and values. (Hence the inclusion of examples such as Dread Scott and “Tongues of Flame”.) The case files include typographical and factual errors, as in the Wojnarowicz entry, which samples freely from two distinct court cases and incorrectly lists the artist’s date of birth. In spite of the bureacratic language used, the anger felt by the researcher who compiled this—no doubt working with scant resources, under pressure of time—is palpable, in part because of this imprecision.

But if the vested interests of the researchers themselves can be glimpsed here and there in its contents, the same can not be said of The File Room as a whole. Its contents include cases of censorship perpetrated by artists or efforts to curtail hate speech, such as the example of Wojnarowicz suing to suppress a right wing pamphlet containing his work. Censorship itself is not portrayed as an absolute evil, but as a process that is central to the workings of art and power.

When Randolph Street Gallery closed in 1998, The File Room’s online database moved to MediaChannel.org, the National Coalition Against Censorship’s website, and eventually, to Rhizome’s own servers, where it will continue to be active and maintained.

In the following interviews, Antoni Muntadas reflects on the transformations of censorship from a physical to a more elusive, digital operation as well as his own relationship with early web culture. Former Randolph Street Gallery executive director Peter Taub locates The File Room in the history of the internet in Chicago, and recalls the early stages of the project’s realization. Rhizome’s preservation director, Dragan Espenschied, explains the efforts required to preserve and re-stage The File Room for Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology. Espenschied also reflects on the difficulty of managing community values in open-submission platforms and on the historical significance of Muntadas’s voice in early web culture.

Antoni Muntadas, The File Room, courtesy the artist.

Antoni Muntadas

DP: I know that the project was in part inspired by a personal experience you had with censorship. Could you provide some more information about this case and about how your proposal for The File Room came about?

AM: Yes, I worked on a commissioned project for Spanish television for two years that was never broadcasted. I didn’t want to create a polemic there because I didn’t live there, so the first opportunity I found to address this issue was an invitation to propose a project for Randolph Street Gallery. I proposed The File Room as a way for people to document their own experience with censorship—a kind of exorcism—and my own experience became The File Room’s first case.

DP: The File Room communicates a tone of skepticism toward early utopian views of the internet. It’s both self-critical and full of modest disclaimers about the information contained in the database. Did you share this skepticism toward the early web while you were creating this project?

AM: I think the skepticism was for the expectations that people had for the future of the internet. People put these expectations on any new medium. They said that videotape would end television and that photography would retire painting. But new mediums simply add to a spectrum of mediums, complementing older mediums rather than eliminating them.

Something I found interesting in internet communication was electronic mail’s precedent of postal mail. This medium was utilized by those in places where communication was very restricted, and therein emerged networks of artists living under oppressive regimes.

DP: The File Room includes nine texts about the work. One of these texts was written by Elisabeth Subrin, who led the research team at Randolph Street Gallery. In the text, titled “An Alternative History: Notes on the Research Process” she mentions in regards to the database that, “objectivity is out of the question.” Do you agree that the database can in no way be objective?

AM: After many years working closely with and about television, I have arrived at the conclusion that there is no such thing as objectivity. Part of the importance of The File Room was that people were asked to talk in first person. It is sometimes very complex and ambiguous whether an experience qualifies as censorship or not, so documenting people’s critical subjectivity is important. An interesting example of this is when an event happened at the Art Institute of Chicago and the director of the school put the case on The File Room. Some students answered, and the project became a platform for discussion. In this case, it wasn’t just the person who was experiencing the censorship who contributed, but also the one conducting the censorship.

DP: I was intrigued by the installation’s translation of digital space into a physical room, filled with file cabinets and lit by a single, uncovered light bulb. Had you imagined this visual interpretation of the digital database all along?

AM: I proposed installing The File Room at the Chicago Cultural Center, which holds the memory of a public library. The physicality of the installation became important for two reasons: the first was the power it held as a metaphor for the intensity of censorship. The installation created a kind of Kafkaesque, repressive, bureaucratic, administrative, and dramatic room. It informed the viewer’s perception of the digital space. Secondly, the room’s terminals served as a crucial form of access to the site. At that time, the web still operated mostly on a military and university level—people did not have it at home or internet cafes.

Of course, now both of these points have changed—the site is both more accessible and less dramatic looking, instead appearing outdated and nostalgic. I never want to change this, because I see the site as a kind of digital artifact of its time. In anthropology, you analyze an object by what elements of its time it accumulated. The File Room accumulated elements of Chicago in 1994 and the state of early web computer graphics.

DP: How was censorship changing in 1994? Were a lot of people thinking about censorship in the world and in regard to the early internet?

AM: Censorship has always been a concern for me, but there were certainly changes in the nature of its brutality and violence at the time. Both political and economic censorship were beginning to transform from a physical state—cutting films or eliminating pages of books—to being less physical, more Machiavellian, and more complex. The File Room uses a digital platform to address these new forms of censorship. Still, since the internet was not very accessible at the time, cases were being faxed and phoned in as well as emailed and submitted through the site.

DP: Do you consider yourself a net artist?

AM: At the time, people started calling me a net artist, but I don’t believe in such categories. I think that, as an artist, you have to be aware of your use of each medium. When you work on a project, the medium is the last thing that you should choose. Come up with concept, process, context, and then figure out which medium would be best to realize this with.

Peter Taub

DP: Could you give some background on Randolph Street Gallery?

PT: Randolph Street Gallery (RSG) was an artist-run space in Chicago, founded in 1979. I started working there in the mid-80s. It was run by artists, directed by artists, and served artists. Many people who worked there were fulfilling many functions: artists as organizers, artists as activists, and artists as curators as well. It was active in the visual arts as well as in installation, public art, and performance—one of the first performance art zines, P-form, was published out of RSG for over a decade.

DP: How were you introduced to The File Room?

PT: When we invited Muntadas to do an installation in our back-room installation space, he in turn suggested creating something in virtual space. There had always been an interest at Randolph Street Gallery in working with artists who were addressing the public sphere. What was particularly interesting about Muntadas was that he had a very sophisticated and longstanding commitment to addressing issues of power, but with The File Room, he created a project that was more of a platform than a sculptural installation.

From what I understand, it was a project he had been wanting to do for a while but hadn’t had the tools or the format to do so. In a sense, it was an ideal project for RSG because we wanted to serve in a catalytic capacity to help artists realize their work. It became a much larger project than we had initially anticipated due to the knowledge base that was required to develop the site, research the cases, and actualize submissions.

DP: Could you tell me about the research teams?

PT: In many of the projects we had been working on, artists were centrally involved in the labor of producing their own projects. Instead, what Muntadas proposed was creating a platform for other people to participate in. This approach was consistent with his notion of creating an open-submission archive with cases of censorship from around the world and across time. Paul Brenner, the gallery’s exhibitions director, managed both the censorship research team and what turned out to be a crucial relationship with a team of computer researchers, and Muntadas came to credit Paul as a co-creator. At that time, these computer researchers were at the very early stages of developing ways for HTML to not only communicate with different computer platforms around the world, but to also support images in addition to text. In fact, when we started on the project, the World Wide Web was not yet an open standard, and Mosaic had not been fully developed or released.

DP: What is Illinois’s significance in the history of the early internet?

PT: When the internet was established, it connected a number of nodal points housed at different universities across the United States. One of these key points was at the National Center for Supercomputer Applications (NCSA), a research institute at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. It’s interesting because Urbana is in the middle of farmland and their traditional strength is in agricultural sciences, but they were also a crucial node in the early internet. At the University of Illinois in Chicago, the Electronic Visualization Lab was a center for some very forward-thinking individuals with one hand in computer science and the other in the arts. A team of graduate students there helped us to visualize how The File Room could exist online, eventually partnering with NCSA students at Urbana to craft the site—which was, at that time, a huge task.

As the site was being built, RSG and Muntadas made contact with people who had experienced censorship, gathering and re-formatting their materials in a consistent way. The first installation of The File Room was at the Chicago Cultural Center, a downtown space with a very open democratic profile. The space was housed at what had previously been the main public library in Chicago, so it was nice having the history of the public library in the background of the project’s first installation.

The physical installation that was first at Chicago Cultural Center and subsequently moved to Randolph Street Gallery was composed of a darkened room with black file cabinets lined on all sides. Every so often, opening a file cabinet drawer would reveal a monitor and keyboard. There was also a table in the center of the room with a computer terminal. It was like being inside of a vault.

DP: Was the internet an interest of other Chicago cultural institutions at the time?

PT: This project felt precedent-setting. It was a perfectly ironic application of the web—to create this open-source online library of censorship.

DP: Ironic?

PT: Yes, because The File Room was subverting the definition of censorship—whether artistic censorship, political censorship, or freedom of expression censorship—as depriving things of their form. The project made these things as accessible as possible. In this sense, it wasn’t just a technical project, but also a conceptual one that questioned and challenged authoritarian power.

DP: Muntadas mentioned how important the installation was in providing access to the website. This seems paradoxical now, but home computing was not popular at the time. Did people start contributing from around the world or was that slow to get started?

PT: Contributions were somewhat slow to get started and we were concerned about how to properly maintain the consistency of those contributions. As I recall, a decision was made to put in place a vetting process rather than letting anyone immediately access the database.

Additionally, online access was slow, especially if you were trying to access images and media clips. The File Room was something that people would utilize by both contributing to and drawing information from, and it felt in some ways that the concept was more powerful than the actual applicability of it.

DP: How was the decision made to move The File Room out of Randolph Street Gallery and into the hands of other cultural institutions in Chicago?

PT: A few years after The File Room was created, Randolph Street Gallery closed. Muntadas’s artwork was a public resource that was imagined to be neither owned nor controlled by RSG—or any single entity, for that matter. There was a sense that we had helped Muntadas to realize this project, and that we had the responsibility to help it continue into the future.

Dragan Espenschied

Q: Where does The File Room fall on the timeline of the early web? How accessible and usable would a site such as this one be in 1994?

A: In 1994, the web existed, but it was in its very early stages. As far as I know, the version of The File Room that exists in our archives was remade in 1998 because its earlier version wasn’t really automated—there was lots of handiwork involved. Apparently, you would submit something and then they would work to put the page up. But I’m not sure because nobody actually knows anymore, no one remembers.

Q: Could you tell me a bit about the conservation and re-staging process?

A: At first, I started making a static web archive. I think that this would have been a viable strategy, because of how participation is thought of in this project—it is very much bound to a certain time of the web and of web culture. For example, in 1994 not everybody had access to the web, and those who did usually got it through universities. These people were more educated, and less likely to swear or write nasty things on the web. Today, we have a different situation. So, while Antoni Muntadas appreciated the static archive approach, he stressed that The File Room is a project with participation at its core.

To preserve this dynamic aspect of the site is more challenging. You would need to constantly update a server so as to avoid it being captured by some worm—or whatever the latest threat is. It might even be the case that, in the future, unencrypted HTTP traffic is not accepted by any browser, or that everyone switches to IPv6, or that the web doesn’t exist at all. All of these kinds of problems would require extra maintenance in order to enable The File Room to accept submission, enter them into a database, and display them on the site.

Instead of dealing with the details of how the site is actually coded and fixing or migrating it every time it breaks, I put the whole server into an emulator. This encapsulation is an abstraction: the question that remains after is "can i make this emulator run again" and "how do I connect to it," instead of sweating over the things that go on inside of it.

This streamlines the problem of maintenance, as lots of other projects use the same emulator. A key goal in digital preservation is reducing the number of problems. The File Room was written in ColdFusion, a scripting language popular in the early 90’s and that I would strongly advice against using today. If I had taken on the project of fully learning that language, I wouldn’t have finished the conservation process by now. Of course, I did have to fool with the project's code a bit in the end—but the idea is that I will only ever have to do this once, and from now on will be maintaining the emulator.

DP: You hinted at how web-based open-submission platforms might have been different in the 90’s because there was limited access. Are there other differences as to how these platforms were viewed in early web culture versus how they are viewed today?

DE: It is interesting that this project utilizes the internet and is against censorship, because at the time it was made, the internet felt like a place where you could be free from all of those constraints. Everyone who was interested in fighting censorship would go on the internet, because it would be the most effective tool to connecting to your peers and making plans without the police watching. Now you could say it’s the other way around—today’s internet has a great deal of surveillance, which is a major part of censorship. In some parts of the world, the internet is very much under the control of the government.

That is also why I think this work is so historically important, because works from this time would often represent the net as a very utopian space. Utopians said that the internet would remain a totally free space for everyone, and dystopians said it would become totally controlled. In a way, they both were right—the web became more accessible, but access to an internet free of corporate and government control still requires a lot of technical savviness. However, I think it’s good to look at how far we have actually come with that utopian ideal, how silly it was, and what utopian ideals we are living with now.

Antoni Muntadas, The File Room, courtesy the artist.

DP: In The File Room’s introductory notes, Muntadas emphasized the subjectivity of the project’s own editing process. How necessary to this platform is the moderation process?

DE: I asked Muntadas, “How much spam does the project actually get—how many robots, fascists, misogynists…” He said that it didn’t get much, and I couldn’t believe that. This moderation process existed in many projects from the early 90’s. For instance, even a mailing list only scales to a certain number of participants before it calls for moderation. Thinking at an even larger scale, a search engine is all about moderation. Even more important than showing, what a search engine is really doing is hiding things from you—it could show you everything in the world, but its value is in how and what it hides.

DP: The project utilized teams of researchers at each location where it was housed. At first, I dismissed this practice as a solution to the lack of web access that existed at the time, but this organized research still exists today. For instance, Wikipedia edit-a-thons are organized to improve the site’s information on topics such as feminism and art, as well as to narrow gender and race gaps in the makeup of the site’s contributions.

DE: Yes, these researchers are exactly a form of maintenance. Wikipedia edit-a-thons are such a good example since, of course what these events are literally providing is access to the net, but more importantly, they are providing a framework for how and when to use it. So, if you don’t think about the web as a thing but as more of an activity, then it is easy to see the importance of these events.

DP: What are your thoughts on the viability of open-submission platforms? How might we imagine solutions to the problems of scalability and inclusiveness?

DE: I’m very much for the idea of open submission. It is just important to learn from successful or unsuccessful platforms in the past: what was the turning point for the system? When did it fall apart or when was it taken over by a certain group? There are lots of ideas about how to prevent this, but the solution is never a flag that you can implement technically—“Click here to agree that you will not act like a terrible person online”—that doesn’t work. There is also the proposal, “If all these anonymous internet trolls would have to show their drivers license before they could access the web, then they wouldn’t spew all this hatred.” This, for example, is the foundational idea behind Facebook. But you can see that this hasn’t solved anything; you can see that people post the most horrible stuff under their real name.

When you uploaded a video to Youtube in 2010 or so, they hit you with the line, “Hey, let’s keep this place fun and clean.” Unfortunately, that means different things to everyone. And at the moment, we are at this point with that platform where videos get randomly censored and deleted by some unpredictable network that’s supposed to be enforcing copyright law.

Setting a tone of inclusiveness on platforms is difficult to do by design. There have been many attempts to create community values in code, or to allow a user-base to design their own values with up-votes, stars, or likes. But you can’t design a system that involves this kind of democratic interaction that won’t privilege the voices of those who have the most time on their hands. This is the case with Wikipedia as well as open-source culture, free software culture, and so on—who can really afford to donate their talent for free? This is why I think that projects like The File Room and Wikipedia made use of events for research, to consciously build both the content and the culture of the platforms.

---

1. http://www.dreadscott.net/works/what-is-the-proper-way-to-display-a-us-flag/

2. http://90.146.8.18/en/archives/festival_archive/festival_catalogs/festival_artikel.asp?iProjectID=8647

3. “Introductory Notes to The File Room” http://thefileroom.org/documents/Intro.html