The Download is a series of Rhizome commissions that considers posted files, the act of downloading, and the user’s desktop as the space of exhibition.

As of January 2018, this work has been taken offline.

Cinema

For most of cinema’s history, film was projected onto a screen in front of an audience, or later, received as signals at home.

Cheap rewritable media changed this one-way system, and with consumer video we developed a physical control over the production and viewing of film and video. Online, this control gives way to agency: we interrupt streaming media, restart then pause, screengrab and record. The viewer’s relationship with the time and space of media is less fixed now. We’re able to generate discourse and broadcast the experience to the network while watching. We create new versions; stories exists on the internet as material to be re-authored, not simply watched. In the networked context, screen-based media has become an asynchronous experience, conflating audience and author. The players are not exactly together.

Roulette

What to make then of Lance Wakeling’s new commission for The Download? Wakeling is a filmmaker, and this work is—and is not—a film. And while it is now available on the network as a downloadable ZIP file, it is not exactly streaming media. Chance, control, and agency are foregrounded in Incantations for the Birth of a Network not because we’re able to easily re-mix and re-author the fifty-eight files included in the ZIP, but because it’s already been mixed for us. This is a story told by a roulette wheel.

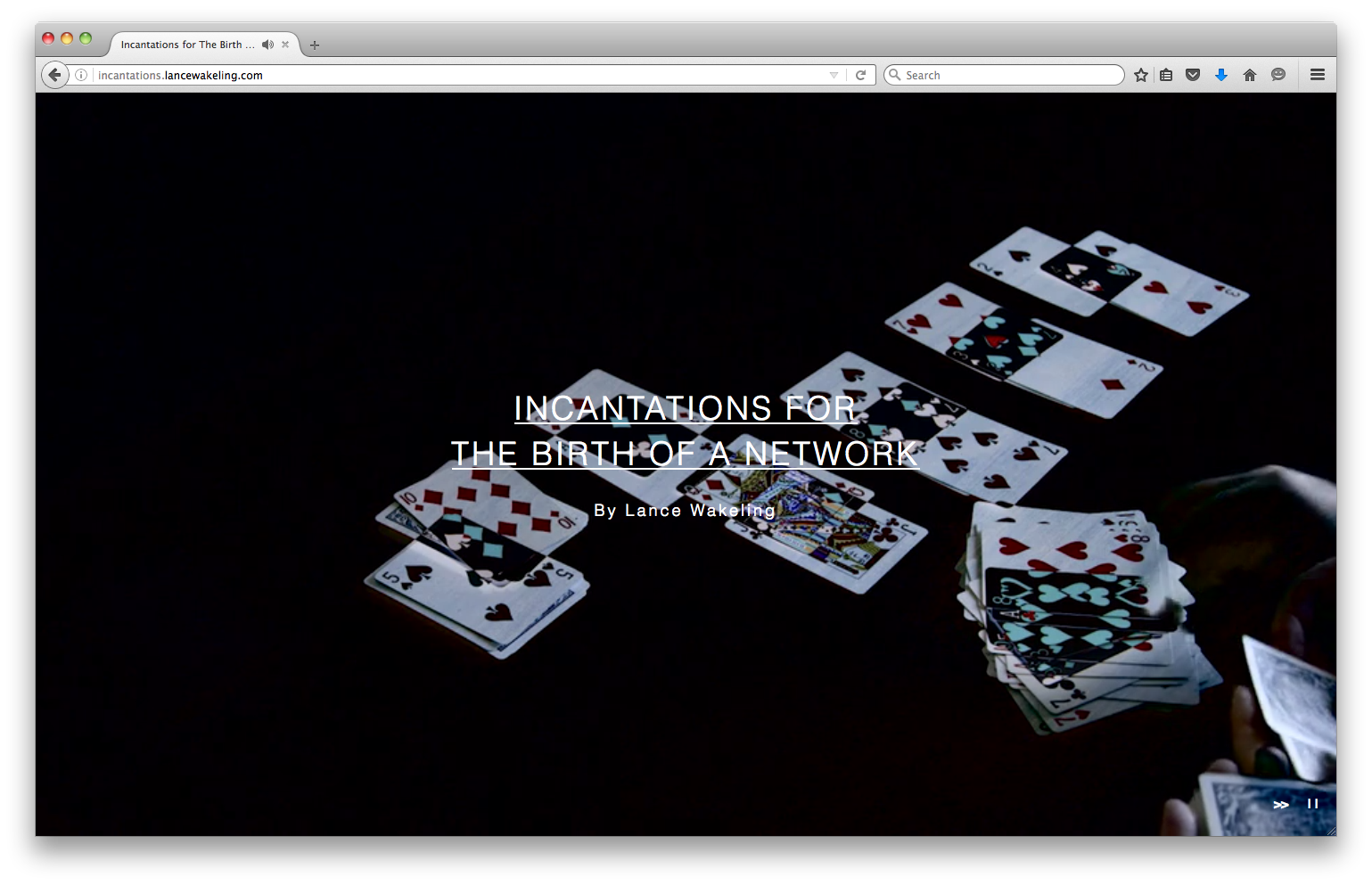

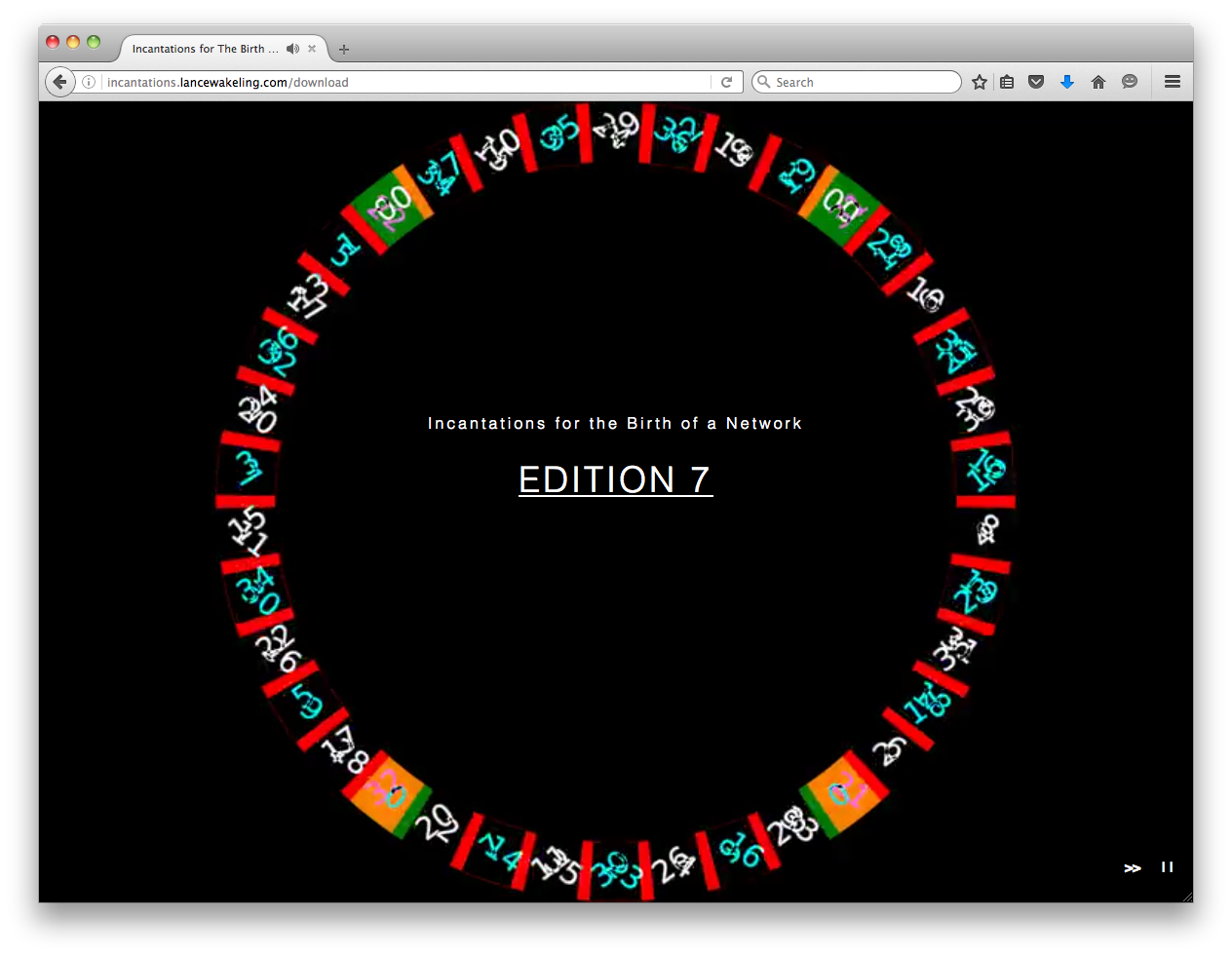

Screengrabs of Lance Wakeling, Incantations for the Birth of a Network (2016).

The sequence begins on Rhizome’s front page with a game of solitaire. Clicking through sets the wheel in motion, while we hear a distant male voice repeating: “The only difficulty is the cesium.” The International System of Measurements has based its unit of time, the second, on the properties of cesium, which is a toxic metal, since 1967. The pulsing machinelike soundtrack accompanying the roulette wheel suggests the decay of radioactive material, or an atomic clock, sounding off at one-second intervals as the numbers spin onscreen. Time as a backdrop—and as an uncertain material to be conquered—is present in Incantations even before the download begins.

Numbers abound in the work. The thirty-six black and red positions of the roulette wheel spin left and right, barely discernable. Clicking through again starts the actual download, generating a new, numbered version of Wakeling’s work each time, one that is not quite unique, but unique enough: each screening of the fifty-eight files presents one of 28.8 trillion permutations, never to be repeated.

Desire

Wakeling calls Incantations for the Birth of a Network “a proto-script for a film,” a story that traces the invention of the computer and the atomic bomb as precursors to the internet. An image included in the download shows an index card with Wakeling’s own handwriting: “This trinity of technologies (the computer, the bomb, the internet) fulfills human desires; desires that have been long expressed through dreams, superstition and mythologies, and which are now in the realm of science.”

The files themselves—JPGs, a TXT, and a PDF—recall a storyboard for a film, or the wall of evidence in an ongoing investigation. Evocative images alternate with writing, all staged against the black background of a flatbed scanner. Wakeling’s anecdotal wanderings through this landscape, and his visits to Los Alamos, Trinity, and the National Archives, retain traces of his hand and voice, flattened and rendered digital for the script of the wheel. But the material itself is barely digital: saved, but not searchable.

If the script is a story of desire, then the roulette wheel is a kind of code that re-writes the story’s desire lines again and again. Writing about another work that references the roulette, David Joselit says that Marcel Duchamp’s Monte Carlo Bond (1938), which staged a faux investment in a strategy for playing neverending spins of the wheel, “is a monotonous, repetitive rehearsal of desire which is always in motion but never leaves its point of departure. Duchamp breaks even.”1 The roulette wheel “establishes a flow of desire — of infinite spins of a disc and settlings of a ball” that eventually doubles back to its starting point, yielding nothing. Chance is the only winner.

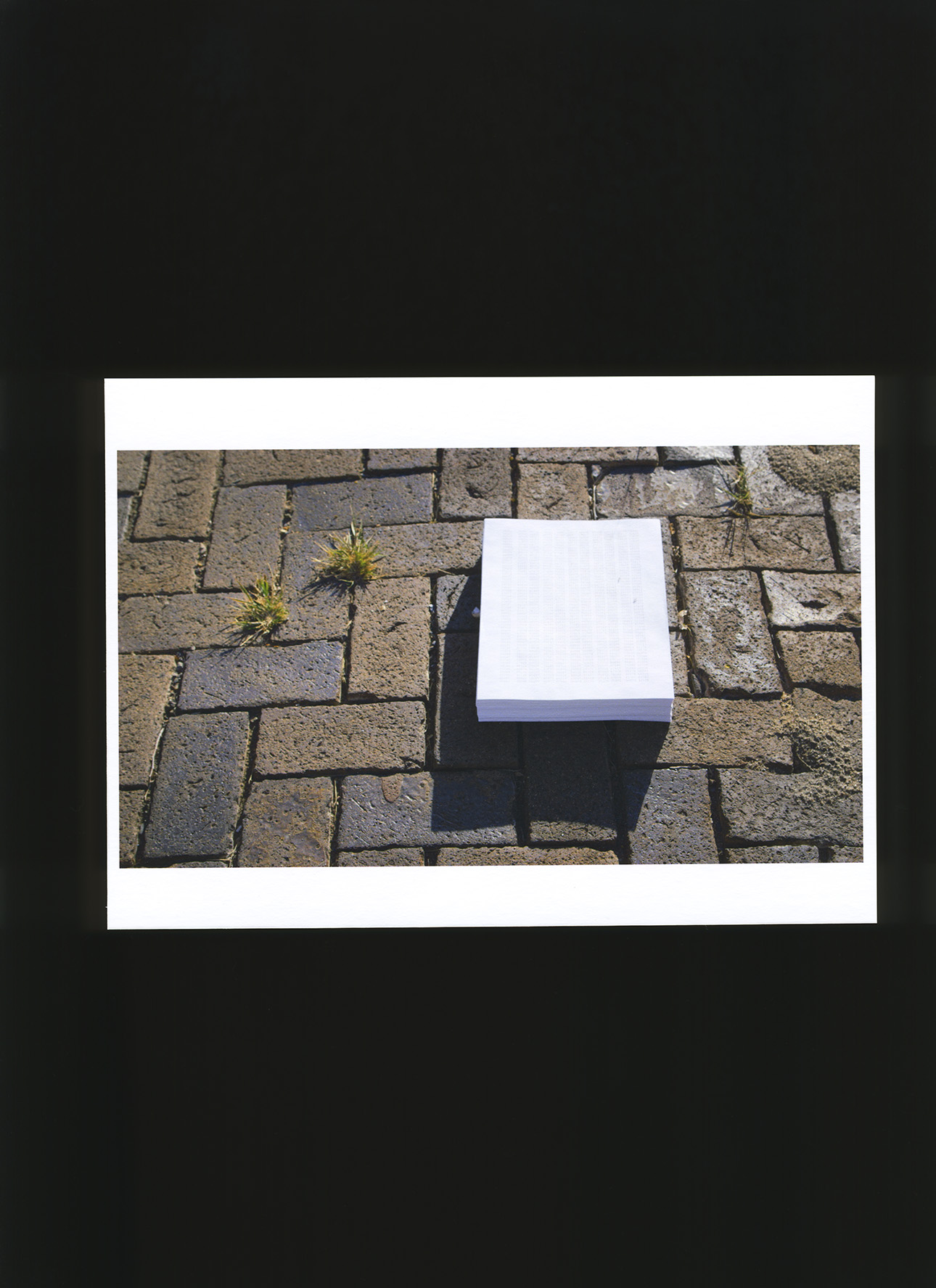

"## scatter-piece" from Lance Wakeling, Incantations from the Birth of a Network (2016). A copy of the publication "One Hundred Million Random Digits" at Lamy, New Mexico. This book was compiled using an electronic roulette wheel by project RAND for use in Monte Carlo calculations.

Screening

Incantations for the Birth of a Network could be read as a passive experience, like sitting under the constant sway of luck’s charms in a casino. But this is no break-even spell. Remember that Wakeling’s work is both a screenplay and a screen-based game to be played. Screening the work—opening, arranging, and animating the stories on a computer screen—enacts Wakeling’s assertion that narrative might be less like a timeline and more like a network, both in its delivery and in the production of meaning. His proto-script signals an active flow of desire, an investment in a future film, as well as the film itself. In screening Incantations for the Birth of a Network, the machine (the counting wheel) and the artist (Wakeling) collapse onto the audience player, who authors the work and settles the bet. The dividend has already been paid: once downloaded, the outcome for an open, neverending cinematic experience is completely in our favor.

Trailers for Lance Wakeling, Birth of a Network (work in progress).

1 David Joselit, “Marcel Duchamp’s Monte Carlo Bond Machine,” October, The MIT Press, Winter 1992.

Rhizome Commissions are generously supported by Jerome Foundation, with additional support from the National Endowment for the Arts.