The Download is a series of Rhizome commissions that considers posted files, the act of downloading, and the user’s desktop as the space of exhibition.

Material Speculation: ISIS/Download Series (King Uthal) by Morehshin Allahyari is the second Download. The 570MB downloadable ZIP file is below. Work from the series also appears on the Rhizome front page through Feb 21.

Can the internet resurrect the dead? The lost art object—be it speculative, missing, or destroyed like a statue smashed by ISIS—now circulates as JPGs, PDFs, and YouTube videos. Untethered from physical matter, these files work to extend life.

Screenshot of ISIS video showing destruction of King Uthal statue at Mosul Museum (courtesy Morehshin Allahyari)

It’s an illusion of sorts; things seem to continue on once they’re multiplied, dispersed and made visible on the network. In the absence of an original, copies of texts and images swarm around and form the missing thing as an imaginary concept in itself. These digital representations might conjure the lost object in archaeological terms, acquiring location, weight, and presence, but they resist fixity. The Buddhas of Bamiyan, which stood northwest of Kabul, Afghanistan for 1,500 years until they were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, are simultaneously gone and forever present. Images of the monumental statues before (and after) their destruction were copied endlessly into art history’s collective memory, first in print, and now as bits moving in and out of search engines and digital archives as the real thing.

Buddhas of Bamiyan, Google Image search

Somewhere between there and not-there, the freely circulating multiple opens up an immensely satisfying space: a metaphysical free-trade zone where an infrathin existence goes unchecked. Dead might not be gone. Aura, less relevant in the digital copy’s persistence, is exchanged for immortality, guaranteed as long as the reproductions multiply and move.

Morehshin Allahyari is an artist and activist who harnesses this illusive condition of the persistent copy; she responds to the violence of cultural terrorism by resurrecting lost objects with stereolithography CAD files for 3D printing. In her ongoing project "Material Speculation," currently on view at Trinity Square Video in Toronto, Allahyari reanimates ancient artworks destroyed by terrorists with a hybrid counterforce of research, digital reconstruction, and 3D printing.

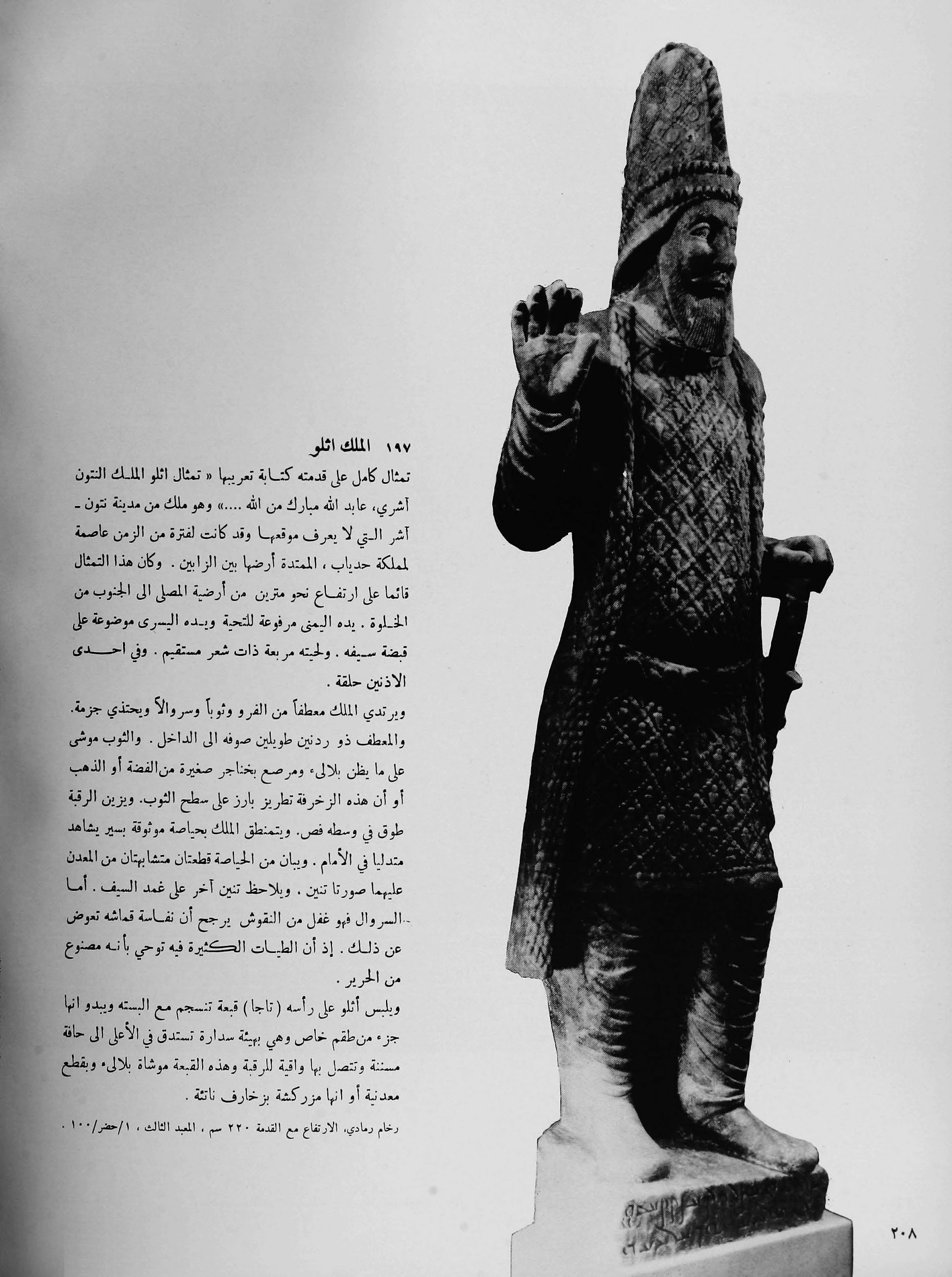

For her Rhizome Download commission, Allahyari releases a dossier of digital artifacts related to one of these lost artworks—a single Roman-period figure from the Mosul Museum, smashed by ISIS militants in June 2014. It portrayed King Uthal of Hatra, his right hand raised in greeting.

Statue of King Uthal (Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, 208)

The .stl and .obj files contained within the ZIP folder are the first 3D models of a lost artwork openly published by Allahyari, who plans to disperse many more. Accompanying the models are ancillary materials and data related to the original statue, other objects destroyed at the Mosul Museum, and her digital reconstructions. Just as King Uthal’s unfortunate destruction in northern Iraq is part of the work’s story, so, too, is its reanimation on the network. Allahyari’s act is an expansive one—with each download to a hard drive, the narrative rewrites itself.

In Allahyari’s project, and more broadly in her and Daniel Rourke’s 3D Additivist Manifesto, we see a call for artists and activists to imagine 3D printing as a radical, political tool for reshaping matter and its digital destiny. Allahyari’s dispersion of the King Uthal files extends this invitation, a poignant act that rewrites material violence with a collective force on the network. To download, share, and print these files is to participate in this additivist act of resistance.

Morehshin Allahyari and Daniel Rourke, "The 3D Additivist Manifesto," (screenshot, 2015)

Created from dozens of still photographs, Allahyari’s models are "same, same but different," evoking the original in a scaleless, placeless version without material conditions. These variables, once reserved for artistic intent, are now given over to the collective. The dispersion of the statue guarantees the persistence of its many divergent versions, stored on hard drives and printed out anywhere, at any time. How might we characterize these copies? Will the sculpture of King Uthal be brought back to life? Perhaps, in the same way that a meme is alive. As the files are posted, downloaded, and printed, different each time, the nature of the thing remains unsettled. In its hybrid state of being and non-being, the CAD model bridges an ontological gap between presence and disappearance—a multiverse of digital cenotaphs. King Uthal’s simulacrum is a mixed-up phantom of itself, actively repairing cultural memory while denying us a conclusion.