The Space Between Us, a new app from David Horvitz, does so little. It’s Grindr in reverse, a post-hook-up tool for conjuring the other, after the fact. While some geo-location apps invite us to visualize the users around us, leading to chats and meetings—zooming in on the physical—this work goes the other way. It begins with a physical encounter and adds distance.

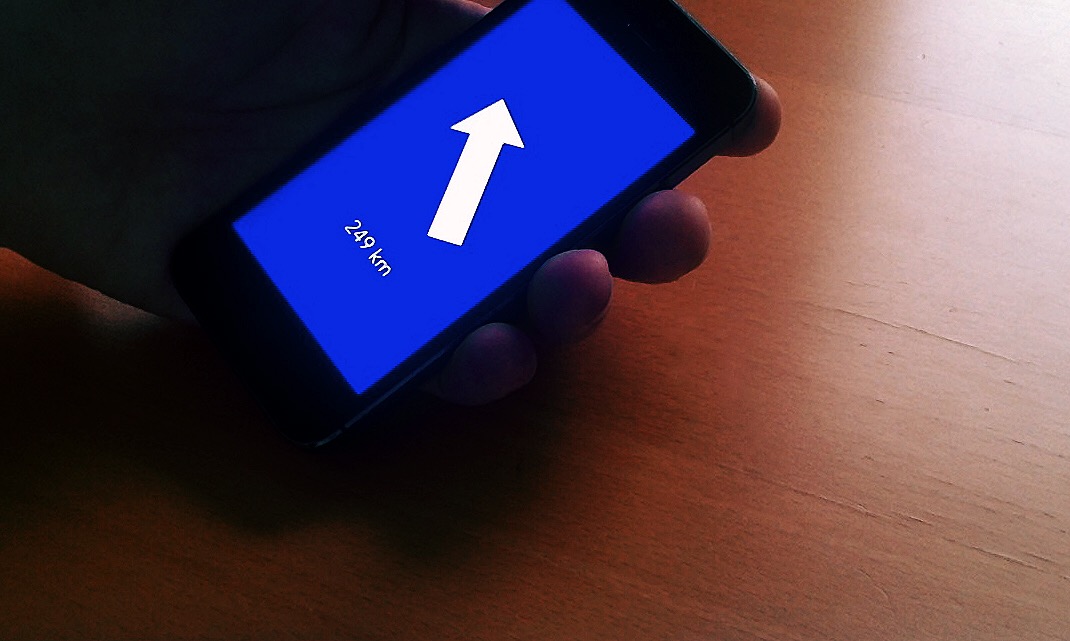

The generic design belies the complex relations the app sets in motion. Designed by Mia Nolting and programmed by Miles Peyton, it draws a dotted line across the planet between two users, as the crow flies, and the connection is intimate and beguiling. Once downloaded, a fat white arrow spins clockwise against an ultramarine (“beyond the sea”) background. It’s dumb. The instructions tell me that the spinning continues until I find another user. The frustration of having no one to play with at first makes me think of Grindr’s addictive optimism, where I’m constantly presented with new players, potential chats and outcomes. What’s more ridiculous: browsing or not being able to?

Twenty-four hours had passed since downloading; the delayed gratification was already trying my patience. Determined to beat the lonely spinning arrow, I pair up with a friend. Our arrows immediately lock, pointing toward each other across the room. The Space Between Us really does its thing when we separate. As the distance between us increases, the arrows never stop pointing. This app is a relational compass. I turn my body to face my friend, wherever he is. The dislocation is displayed in kilometers, but that space between us is collapsed in emotion and thought.

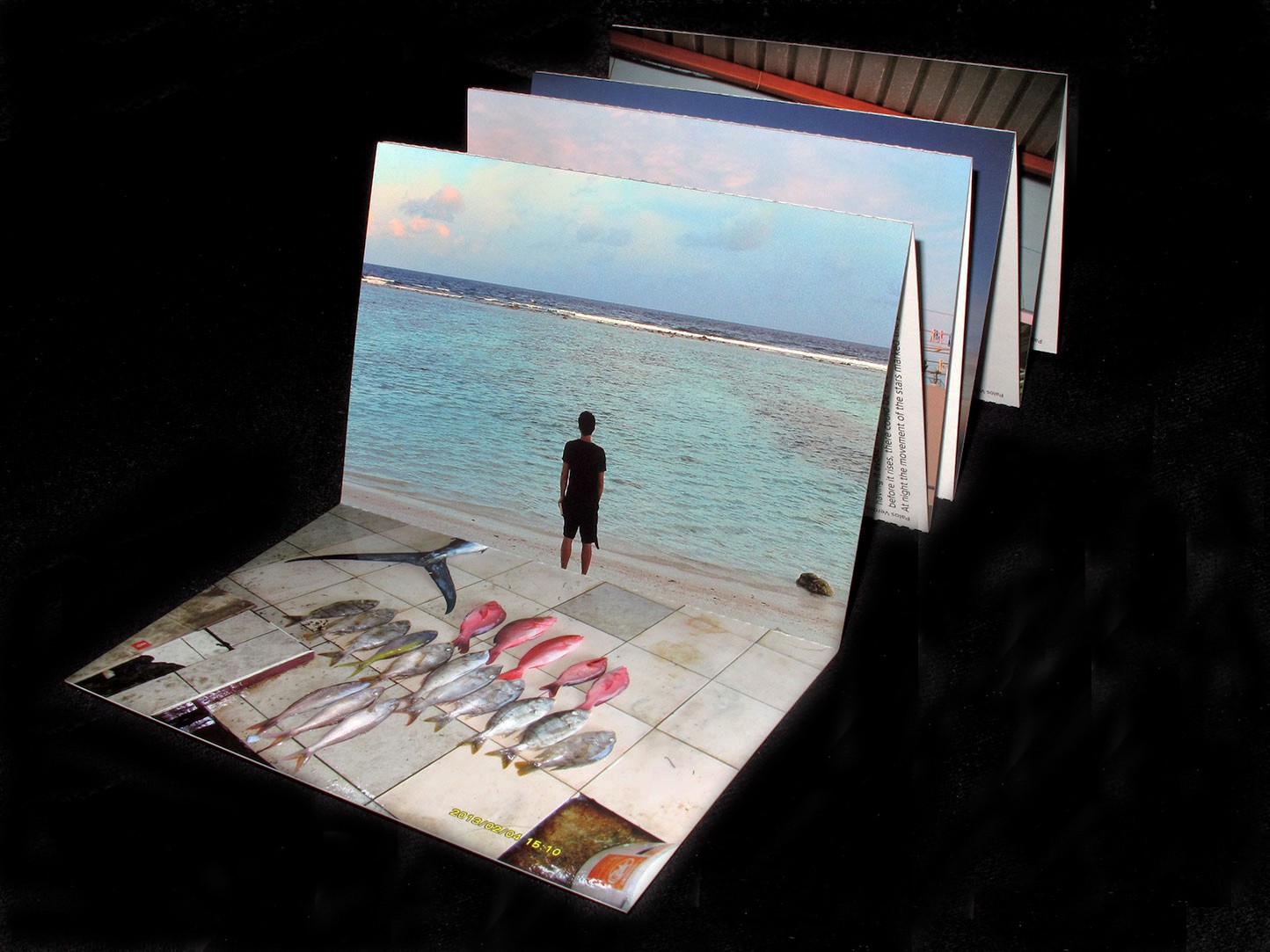

At this point, there’s nothing else to do but imagine his presence in relation to mine. Like much of Horvitz’s work, time and space are presented in plain terms, but are not to be taken for granted; constructs are at play, relative and personal. In The Distance of a Day (2013), a related work, Horvitz filmed the sun rising from the east on one iPhone at the same moment that his mother, at a location far away, filmed it setting to the west on another; later, the two devices were displayed in a gallery, side-by-side, a spatiotemporal collapse through a single event. Horvitz used the movement of the earth to connect himself with his mother; he says the work is the sun in their eyes at the same time. Bodies facing each other across a large distance, looking towards one another, imagining the other in a moment.

David Horvitz, The Distance of a Day (2013)

For the next few days I look at my arrow, imagining my friend from time to time, 0.5 kilometers, 2.5 kilometers, 249 kilometers away. I picture him downtown, going home to Brooklyn, on a train traveling to Rhode Island. Turning myself toward his physical presence “out there” in the world is an odd, vaguely intimate feeling. Surveillant, almost. I think of reasons to turn our bodies in relation to the planet: the sun, moon, weather, gods. A few days later, I tap the arrow ten times and it vibrates; we are disconnected. Released from our strange bond.

Unlike functional apps that feature maps or profiles, The Space Between Us describes users only in relation to each other. Horvitz uses minimal means to link us up beyond physical location, if we’re open to it. All we need is an agreement and somewhere to set our sight.