Still from Send/Receive

In recent years, the significance of artists' magazines has been cemented by the proliferation of exhibitions, panels, and monographic studies devoted to independent publishing endeavors. Not merely side projects or promotional vehicles, such magazines constituted, as art historian Gwen Allen argues in her 2011 book Artists Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art, a form of exhibition space in itself, a central site of postwar artistic experimentation.

The magazine was, in a sense, the ideal form for the “dematerialized” art practices taking hold in the 1960s and ‘70s, which were often rooted in language and typically exhibitable solely in the form of secondary documentation—textual descriptions, instructions, or scores; diagrams and maps; and photographs. At the moment when artists were vehemently challenging the authority of the institutions that mediated between their work and its audience, as well as the attendant commercial system that conferred value based on the saleability of the object, the form of the magazine offered a way to circumvent existing structures—to disseminate projects and ideas directly to an audience, and one that was, at least theoretically, broader than that of the museum or gallery, and more geographically dispersed.

Among the storied magazines of the ‘70s, Avalanche, founded by artist and curator Willoughby Sharp and filmmaker Liza Bear in 1968 (the first issue appeared in Fall 1970), is perhaps the most iconic in terms of capturing the ethos and character of the period’s artistic climate. The privileged editorial form of Avalanche was not the critical essay or review, but the artist interview and it often turned pages over to artists— including Gordon Matta-Clark, Hanne Darboven, and Richard Long —to design their own spreads. Likewise, its “Rumblings” section functioned as a form of pre-internet global art-world message board where artists could submit announcements of upcoming exhibitions, projects, and publications.

Ephemeral and inexpensive, Avalanche was, as Bear described, “a cross between a magazine, an artist book, and an exhibition space in print. Basically, it was devoted to avant-garde art, from the perspective of the artist.” Avalanche, and periodicals like it, were attempts to rethink the art magazine in terms of both form and content, conceived in response to mainstream publications like Artforum, which were dominated by the critic’s voice and implicitly bore the influence of curators and dealers. However, Avalanche was also a network, a decentralized mode of distributing art that aimed to shift the site of reception beyond institutional boundaries.

Avalanche had always been receptive to new media—the entire 9th issue, published in Spring 1974, was dedicated to the January 1974 Video Performance Exhibition at the SoHo alternative space 112 Greene Street—but the static nature of print obviously limited their ability to engage with it beyond publishing still images and discussions with practitioners. However, following the publication of Avalanche’s final issue in the summer of 1976, Bear and Sharp largely devoted themselves, both collaboratively and independently, to projects that engaged developing technologies in video and telecommunications—especiallytelevision.

In September 1977, Bear collaborated with artist Keith Sonnier, along with Sharp and several other artists, on Send/Receive Satellite Network, a two day project for which the artists set up a two-way satellite link between New York and San Francisco. Using a CTS satellite co-owned by NASA and the Canadian government, artists on either side of the country were able to collaborate in real time, with the resulting program broadcast to viewers on Manhattan Cable’s public access channel. The project unfolded in two phases, with the first considering the implications of satellite technology and the second a demonstration of its collaborative and artistic possibilities.

In the latter phase, the artist-participants—Margaret Fisher, Terry Fox, Brad Gibbs, Sharon Grace, Carl Loeffler, Richard Lowenberg, and Alan Scarritt in San Francisco, and Bear, Sharp, Sonnier, Richard Landry, Nancy Lewis, Richard Peck, Betty Sussler, Paul Shavelson, and Duff Schweninger in New York—probed the project’s unique conditions of production: Scarritt, for instance, created a feedback loop by pointing a video camera at the television set at the ground station in San Francisco and transmitted the video via the satellite to New York, while dancers Lewis and Fisher responded to each other’s movements from opposite sides of the country. Describing the questions informing Send/Receive, Sonnier and Bear wrote, “What are the implications of simultaneity? Of instant exposure and instant response?”

As Sonnier noted in an interview with Bomb magazine, one of the most significant aspects of Send/Receive was that it had happened at all: “The media is so completely politically controlled [that] the focus became less and less about making work as illustrating this huge propaganda tool. Acquiring that tool was the political thrust—making that tool culturally possible….Send/Receive was the culmination of a learning experience.” With Send/Receive, the artists not only explored the artistic uses of satellite technologies and the nature of telecommunications as a medium, but also began to articulate the political potential of artists’ use of them.

Following Send/Receive, Bear created a series of public access television programs, some with Sharp’s involvement, which aired regularly on Manhattan Cable from 1979 to 1991. Whereas Avalanche had directed itself implicitly against the mainstream art world and its institutions, the projects oriented around telecommunications were fundamentally concerned with the intermingling of governmental, corporate, and military interests that determined and regulated access to information on a global scale. Using television as a medium allowed them to intervene in this system from within, disrupting it by harnessing television’s potential to disseminate information and by detourning its visual and narrative tropes.

The Very Reverend Deacon b. Peachy: Part 1, 1982, excerpt, SERMON IN SHOES (Part of Communications Update, 10 March, 1982)

The first of these programs, the “Warc Report,” was a 10-week series produced by Bear and Sharp, along with Rolf Brand and John Howkins, that presented coverage and commentary on the 1979 General World Administrative Radio Conference in Geneva—a conference held at 20 year intervals in which delegates from member nations of the UN’s International Telecommunications Union met to negotiate issues concerning access to, and regulation of, telecommunications services and technologies. Though, as the producers of the “Warc Report” noted, the decisions made at the conference would impact every aspect of the development and direction of the telecommunications industry worldwide for the next two decades, it received virtually no mainstream media coverage; the “Warc Report” was explicitly designed to counter this “information moratorium.” Each of the ten episodes addressed a different aspect of the conference and the implications of its decisions, ranging from “What is WARC?” to “Military Uses & Foreign Policy,” combining live coverage of the conference with discussions about telecommunications issues more generally.

In her essay “Public Access: The Second Coming of Television?” published in the journal Radical Software in 1972, Ann Arlen argued that the public access cable channels that had recently been initiated in New York represented “a chance to change the course of the nation’s most promising and least fulfilled mass communications medium.” The significance of public access for Arlen was not only in its ostensible democratization of the medium, offering the possibility of a TV show to anyone willing to put in the effort, but, more importantly, that it represented “our first experience of an electronic mass medium through which people may talk to other people unmanipulated by media professionals”—a means of presenting events not as packaged “news,” but as information, communicated from person to person. The “Warc Report” was precisely such a program, filling a crucial gap in mainstream media coverage, but doing so in a manner antithetical to commercial news broadcasts. It was designed to present the viewing public with information as opposed to news, and to do so through the very medium that would be broadly impacted by the decisions made at WARC.

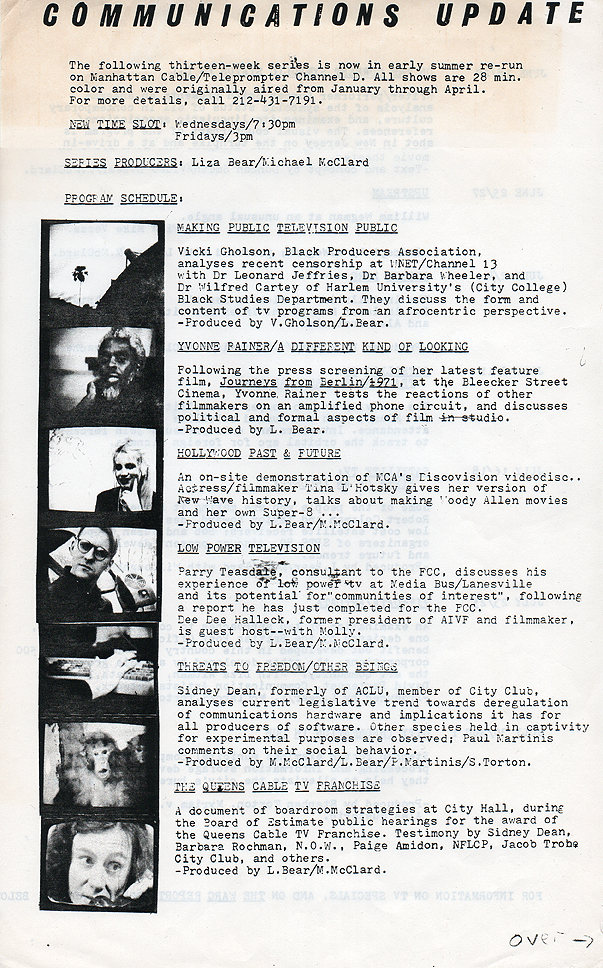

After the conclusion of the "Warc Report," Bear began producing "Communications Update," a weekly 28-minute show with segments created by artists, most of whom shared equipment through a video co-op. Like its predecessor, much of the first season was devoted to media politics and developments in telecommunications—segments included "Making Public Television Public," for which Vicky Gholson discussed censorship with professors from City College's Black Studies Department, and "VIEWDATA/APTDATA," which looked at recent computer networking projects. However, it also included more idiosyncratic material by artists that moved well beyond the expectations of television programming. In William Wegman's segment "Upstream at an Unusual Angle," for instance, the artist was filmed in fishing gear, interacting with amused passersby as he attempted to fish in the middle of a crowded—and waterless—public space.

Politics never disappeared from Communications Update, but in successive seasons, it was increasingly oriented toward commissioning and broadcasting artists’ projects on a wide range of issues rather than focusing solely on what Bear described as the “new world information order,” and in 1983 the show was renamed Cast Iron TV to reflect this shift. In a statement that same year, Bear described the show as “play[ing] freely with media conventions, drama/documentary, comedy and satire. It hovers on the bounds of fact and fiction, rides the dramatic potential of fact, the narrative potential of reality, but also toys with theatrical illusion adroitly.”

Decidedly eclectic, the programs on Communications Update/Cast Iron TV ranged from experimental film and video works by local and international artists—the Croatian artists Sanja Ivekovic and Dalibor Martinis produced two features on video art in Zagreb—to segments that explicitly drew on television’s vernacular. One of the show’s recurring programs, the Very Reverend Deacon b. Preachy, produced by Milly Iatrou and Ronald Morgan, aped the format of late night televangelist shows, with satirical sermons insisting that their viewers send them no money. For Bear, providing artists with the opportunity to create the media—and giving audiences an alternative to commercial programming—was implicitly political, regardless of the nature of the programs themselves. As she stated in a 1983 article in The Independent, “We used the public channels because they were the only consistent media outlet that we had—a regular weekly outlet as opposed to sporadic exhibition of videos in alternative spaces. The aim was to provide artists an active role in the making of information, as opposed to being passive receivers of it.”

While these telecommunications-based projects can be seen as an extension of Avalanche into other media formats, opening up another avenue for artists to connect directly with their audiences, they might equally offer a new perspective on the magazine and its goals. They emphasize the extent to which Bear and Sharp were interested in exploring, utilizing, and subverting mass media—not only circumventing the institutions of art, but intervening more generally in the structures that determined the form and content of what the public could see and hear.