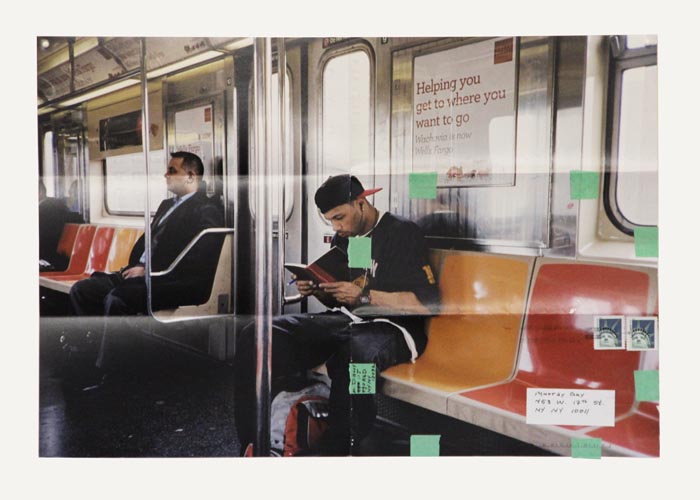

Moyra Davey, from the exhibition Spleen. Indolence. Torpor. Ill-humour, (Murray Guy)

One of my earliest memories is getting hit in the face by a book. I was two; we had just moved to Dubai, and were staying with another family for the first few weeks. While we were playing, their younger son threw his book at me. It cut open the thin skin below my right eye, just above the line now demarcated by insomnia’s purplish bruisings. I remember only fragmented flashes. The green Small World Library hardback with Goofy on its cover, the tears, and the blood—so much blood that the book retained a rusty stain on the spine.

The scar has since stretched and faded to a gathered curve, barely discernible to the touch and perceptible only if you know where to look. As I grew, I accrued many other scars, each with its own story, but this one remained special: my own facial bookmark. Like a tribal mark or that left arm vaccine scar that quietly signifies which global sphere you’re from, I had been struck by the weight of a book

And read I did, as if to fill up this hole that the book had gouged in my face—compulsively and voraciously, and at every snatched moment I could. Yet Dubai’s public library system was anaemic at best, and its bookstores, with their politely aligned new titles, antiseptic. Summer visits to India became all the more rarified as a result. Here, finally, pavements were hedged with booksellers, and inside, up rickety staircases and under the eye of equally rickety old men, were shelves heaving with books. These bookstores smelled like the ones I had read about: all heady with the intoxicating lignin of tomes gone to seed, mixed in with that slightly musty dampness unique to monsoon season.

Even in this bibliophilic paradise, however, lurked a sense of spoilage, insistently asserting itself like the background static of an AC. No matter how greedily I read and reread, I could never hope to possibly open—let alone own—even a fraction of the books I saw. And that’s to say nothing of all the books I had never even heard of, but was still painfully aware were out there.

Later on, college would highlight in relief just how much I hadn’t read. Each semester I took far more courses than I could legitimately handle, and reading became consumptive instead of submersive. It became good enough to quickly read each text just once; a slower savouring could come later. On visits home, I would fill my suitcase with that semester’s texts in hopes of rereading them—properly, this time—but they always remained in accusative stacks on the floor, neglected in favour of my childhood favorites. As much as I wanted to build a library and surround myself with books, NYC storage concerns colluded with a sense of self-exhorted acceleration to shift my primary reading format from books, to PDFs, to Twitter and tabbed browsing.

Here, again, was that same urgency transposed from page to screen. Do you know the feeling? That sharp, almost adrenal jolt when you open just one more tab and all the favicons disappear to give you a segmented line of characters? You can’t increase your screen resolution much more, but keep the pages open, just on the off chance that you might actually read them. Perhaps you quickly scan in order to close a tab, yet find yourself clicking on “History” just moments later, just in case you missed something. Perhaps you feel guilty about not giving each piece the undivided attention you once lavished upon your books, but often, just knowing the dust jacket-like gist seems to be enough. You consider developing an Instapaper habit, but don’t trust that you will ever train yourself to go back, sit down, and read them at leisure. Because should you manage the impossible, and find time to actually read them after the fact, won’t it be too late? Won’t the conversation have moved on?

This kind of pearl clutching over time poverty and the whirling hyperkineticism of the Web is nothing new. A few decades into the Internet, the browser has become cemented as the new battleground. At face, debates about the experience of reading online rest on a collective nostalgia for the book as an aesthetic object. What’s really at stake is the practice of reading itself: when, where, and on whose platform.

Relevant here is what Jack Cheng has conceptualised as the ‘Slow Web Movement,’ using the metaphor of slow and fast foods. In the Fast Web (“a cruel wonderland of shiny shiny things”) our timelines, dashboards, inboxes, and RSS readers are overflowing with dubiously recycled styrofoam. Against this real-time heartburn—overcalorific and cholesterol laden—he suggests we instead privilege timeliness. That we forgo the whizzy randomness of the Fast Web in favour of a compartmentalised sense of rhythm, consuming media only when we have the time to give them our full attention. Instapaper becomes reframed as ‘turn based reading,’ while email becomes similarly gamified as ‘turn based communication.’ “What next?” becomes “when next?” Coupled with portion control, specialist apps, and productivity systems, the Slow Web ethos promises a healthier, happier, more self-satisfied life. Or to refashion Michael Pollan’s food rules: Read online. Not too much. Mostly #longform.

My biggest beef with the Slow Web Movement, however? It hinges on self control and delayed gratification, and moderation was never my strong suit. I’ve never been able to maintain a Google Reader or productively use any kind of RSS service; ludicrous as it may sound, I read everything at source. No matter how much I organise and breadcrumb subscriptions, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m missing out. Rather than limit myself to the curated CSA inboxed newsletters, I want to devour it all; what was once an ambient AC hum is now more akin to roaring static. It’s a tower of Babel out there in the world wide web, and I love that about it.

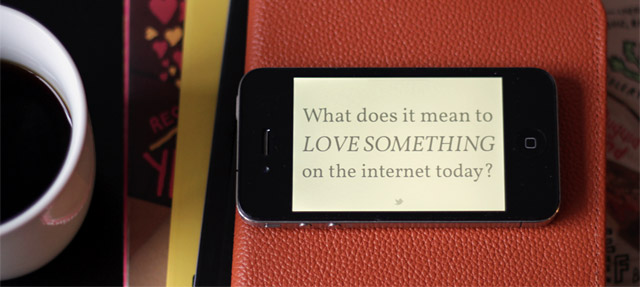

Caption: Robin Sloan, Fish: a tap essay (2012)

Robin Sloan’s Fish App for iOS takes another approach to recreating an immersive reading experience. Its design is arresting—pastelised and in full screen, you are straitjacketed into focusing on just one quiet sentence or phrase at a time. To move through the essay, you tap the screen; there is no back button. Sloan juxtaposes the qualitative differences between liking or favoriting, and loving, noting that when we love something on the internet, we “pluck them out of the flood and put them on shelves and playlists and home screens.” We put them in places where we can see, and easily return to them. Watching something twice becomes a radical act; reading something twice is one of love. Yes, you can download things to read later, but the ultimate problem with the Internet, in his estimation, is that it has no album view. Put another way, the problem with the Internet is that it is difficult to build a library.

How then do you return to things on the Internet? And what does it mean to amass a digital library, and not an archive? Is it about the visual metaphor, about displaying your links and files on an iOS-like interface? The ability to browse your collection, to see it in shelves and stacks and file folders instead of just calling it up via a search?

With finite disk space, however, comes the familiar old storage anxieties—even the Fish App, in its very form, dredges up the spectre of home screen clutter. Despite your best attempts at a taxonomy of spareness, hard drives fill up quickly with PDFs and MP3s. You devise new rules to spring clean your digital hoard: if you haven’t watched or listened to this file in a year, into the bin it goes. Ikea unfortunately doesn’t make storage solutions for files; unlike physical books, they are all too easy to delete.

So the tabs stay open. They haunt you, and perhaps guilt you with baleful, anthropomorphised glares. In a way, they are a discursive equivalent of the decidedly frenzied urban condition, ‘fomo,’ or ‘fear of missing out.’ On events, on parties, on shows, on things that you should have already read and be conversant about. So you get on the train; so you open a new tab. It’s much the same with books—piled up on tables, Jengaed on the floor, waiting. As if owning and beginning the book is tantamount to having read it; as if by surrounding yourself, you might magically learn by pure osmosis.

And now I’m thinking of these gorgeous, searing lines from Nicholas Rombes’ “Julia Kristeva’s Face,” which have remained screenburned into my head since I first read them.

The Kristeva book was like a hot coal. It burned through desks and tables and the seats of chairs. It singed the carpeting. It glowed at night in a regurgitated blood orange. It misplaced itself. It flipped itself over in the dark like a fish. I had to put a brick on it to keep it still.

That pneumatic urgency, where a book bristles, and demands, and makes its presence felt? You have to actually first begin reading, and get stuck in. Except—unlike tabs, unlike files, unlike the now-you-see-it-now-it’s-404 current underwriting the internet, books won’t leave you, and instead stay, patiently stacked until they are read. But what if this wasn’t the case? What if the books on your shelves began to wipe themselves with time, a reader’s nightmare akin to the writer’s productivity app, Write or Die on kamikaze mode? Argentinian indie publishers Eterna Cadencia have created just that, with The Book That Can’t Wait, an anthology of new authors. The book is printed with a special ink that begins to fade as soon as it is opened and exposed to sun and air, with the words disappearing completely within two months.

My instant reaction is positive. Their explanatory video is rich, slickly produced, and tugs at all the right bibliophilic heartstrings. As they explain, “There’s a lot of literature out there that doesn’t deserve to wait on the shelf. And ours won’t wait at all.” Like the talking avatars dissecting experiences of online reading, Eterna Cadencia are trying their best to renegotiate the way we read online—when, where, and using whose hardware. Instead of slowing down reading to the measured rhythms of the codex, however, the BTCW speeds it up to the frenetic tempo of tabbed browsing. And in a landscape already saturated with lazy skeuomorphism, it seems hard to argue against. Why slavishly make the screen look more like a page when you can make the page feel more like a screen?

Aesthetics aside, it’s important to interrogate what this kind of marketing strategy actually means. Who benefits? The publisher, certainly, and perhaps the authors, if only for the publicity. The reader, however, loses a lot: the ability to keep a beloved, dog eared book around for years, to dip in and out of it at will, and to lend, gift, or resell their copy; to build a library. As for booksellers, already beleaguered in the best of economies? An entire ecosystem of second-hand bookstores, both brick-and-mortar and online, will crumble, as will prison literacy-type programs, that sustain themselves upon donated materials.

The disappearing ink technology in itself opens up some broader questions. Used for newspapers, flyers, office printouts and other limited-use ephemeral literature, it could revolutionise paper use and recycling—albeit with the risk of creating a new hierarchy of printed matter. More chillingly, it can be seen as an analogue application of DRM to the printed page, following in the footsteps of the e-book. Recall Amazon’s deliciously Orwellian blunder in which it remotely deleted copies of Animal Farm and 1984 from Kindles over copyright claims. In the process, it alienated customers who were shocked that something they had purchased was not theirs to keep. In some cases, people even lost their annotations and notes in the margins—original, sometimes scholarly work—which raised further questions of ownership and impermanence.

Returning to that early recollection of getting cut open by the crushing physicality of a book, I called my mother. To ask about the incident, about the gushing blood, and did I have to get stitches? She sounds surprised I remember it, and tells me it was not much more than a little nick. Not much blood, no fuss, and certainly no surgery. That was memory, writ in an equally precarious kind of disappearing ink. For it to be remotely debunked and wiped clean—reformatting my early childhood, in a way—so neatly is unsettling.

When we enthuse about print books, we talk about them like they’ll be around forever. Such is not the case; like memories and scars, they fade and warp over time. Consider the spectrum from mass-market paperbacks that very quickly become unbound and jaundiced with age, through to more expensive texts that might be printed on acid-free paper. Rarer texts get a panopoly of preservation treatments from binding and display cases through to environmental controls that limit exposure to heat and light. In their attempt to rejuvenate print, Eterna Cadencia just might be sounding the death knell, in insisting that we treat each book with the white-gloved, sacralised care we accord to museum and archival pieces.

I’m imagining, too, what future bookstores might look like if more publishers adopt the technology. Perhaps they will come to more closely resemble hypermarket cold rooms, with sterilised, vac-packed books. Next to the register, a wall of single-or-multiple use shellacs, that reveal the invisible ink, and grant you a painted on-access to your words for a limited time. A new cottage industry of dry cleaners that chemically treat and process your books to make them legible for a time. And small, microbial clusters of stealth cells, in several nowheres, gather together each week to figure out how to hack the page.