This month I’m traveling through southeastern Europe from Venice to Athens, where I’m looking at art and blogging. Part one of the travelogue is about Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Before the Internet Pavilion, there was the first meeting of nettime at the 1995 Venice Biennale. Vuk Ćosić, one of the core participants, told me about it over lunch in Ljubljana last week. Internet theorists and artists gathered for three days of discussion just upstairs from Club Berlin, a non-stop rave where art stars worked the bar. “I remember Joseph Kosuth handing me a beer,” Ćosić said.

The rave was a recurring theme of the four days I spent in Slovenia, and there seemed to be more to it than the Slavs’ enduring love for techno. My visit happened to coincide with the opening night of Sonica, a sound art festival, and the kickoff featured Andi Studer and Matt Spendlove’s Netaudio Ping Pong, where two players build dance music by taking turns at composing four-bar phrases on mixers installed on two ends of a ping-pong table. Škuc, a gallery that has been showcasing progressive art since 1978, was hosting a “live archive” of Slovenian video art from the 1980s and 1990s, and I spent an hour watching works by Mirko Simic, including distillations of his veejay acts at parties fifteen years ago. On Wednesday night, Luka Prinčič performed at a small theater in a university’s basement; between the somber, wordy beginning and end, he danced himself into a sweat wearing silver tights and sparkling tank top. The next night, after a presentation at Kiberpipa where he demonstrated his Puredata modification that introduces elements of probability to the dance tracks he writes to accompany his pieces, Prinčič said he associates the rave with a temporary manifestation of an aspect of a person or group that is usually hidden.

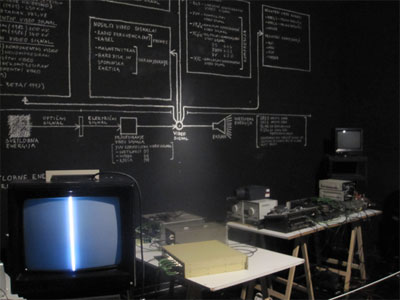

Several of the arts organizations I contacted in Ljubljana—including Mota, the organizer of Sonica, and Aksioma, which produced Prinčič’s performance—operated in the same way, like party promoters who generate networks from their invisible studios. The method is characteristic of Ljubljana’s arguably most famous contribution to contemporary art, NSK, or Neue Slowenische Kunst, the loose body of the band Laibach, the theater troupe Noordung, and Irwin, a group of conceptual artists. They founded the imaginary state of NSK in 1991, and it continues to manifest itself in the NSK passports (which became so popular that the Slovenian government had to officially announce that they were not the same as Slovenian passports) as well as personal connections between citizens. (Irwin further explored this direction by constructing a canon of Eastern European contemporary art, which still accepts proposals for additions on its site at East Art Map). The conditions of Ljubljana’s current art scene, however, are not a conscious effort to develop the older generation’s traditions of invisibility, but a result of financial restrictions. Even if an arts nonprofit might like to have a roomy home base, there is too much artistic activity in this city of 300,000—and too little support from private collectors or patrons—when all the groups are competing for the same pots of municipal, national, and EU funding. Klemen Robnik, director of Kiberpipa—a hackers’ club that also hosts a museum of obsolete computing equipment and organizes a biennial HAIP festival—said the state should supply more money. “It seems to me like the state already gives a lot,” I said. “Yes,” Klement agreed after a pause. “But compared to what the state gave when it was Yugoslavia, it’s not much.”

Kiberpipa, unlike some of its peer organizations, does occupy a physical site, but it is almost undetectable, tucked in an unmarked basement far from the city center, a place dominated by a generic, middle-European prettiness. Cobblestone pedestrian promenades wind between stately old buildings that now hold identical cafes, where loungey house music is piped to the customers relaxing at the sidewalk tables with pizzas and cocktails. For a city of its size, Ljubljana has an inordinate number of salons selling faux-modernist paintings and funky vases. The first meeting of nettime in Venice in 1995 raised the question of whether the contemporary city is defined by its walls or the immaterial networks that move within them; in Ljubljana, the contrast between the two—at least from the perspective of my brief visit—looks especially sharp.