(Source: The Single Wing Turquoise Bird's site)

Editor's Note: Robin Oppenheimer will present a longer version of this paper, interspersed with rare clips and documentation, on Saturday April 18th at 8pm during Aurora Picture Show's annual Media Archeology Festival in Houston, Texas. Psychedelic light shows are the focus for this year's festival, which is curated by Bree Edwards. Click here for more information about the Media Archeology Festival and a schedule.

Introduction

In 1965, multimedia artist Stan VanDerBeek wrote that "language and cultural-semantics are as explosive as nuclear energy. It is imperative that we (the world's artists) invent a new...non-verbal international picture-language"1. He foresaw that future “image-making” technologies would be needed to develop a new “picture-language” to communicate to all people the threat of global annihilation. I believe that psychedelic light shows originating on the U.S. West Coast in the 1950s were part of the beginnings of this rapidly developing world language that is now more evident with newer digital media technologies. Along with other counterculture activities such as taking hallucinogenic drugs, light shows evolved as a means of connecting people and helping raise individual and collective consciousness outside the mass media spaces of TV, cinema, and radio. They were among the first primitive attempts by artists to appropriate many of the “new” analogue communications media technologies - photography, film, audio - and add the images, beat and lyrics of popular culture and music to create an immersive mediated environment embracing both the performers and the audience in a transformative sensorial experience.

The light show artists I’ve met and researched tell great stories of how they could feel the people dancing in the room responding collectively to the music and their projections. As pre-electronic media folk artists, they learned quickly that they could tap into the group consciousness of their audience by improvisationally connecting layered collages of images both abstract and representational to the lyrics and rhythmic beat of rock and roll. The immersive, mosaic quality of light shows, when mixed with drugs and loud music, provided a powerful means of altering one’s consciousness and connecting to new ideas and ways of seeing the world that were outside mainstream media.

My essay will provide a brief overview of the histories of West Coast light shows, with a focus on my original research into Pacific Northwest light shows. It will also connect light shows to larger contemporary art histories that include the avant-garde art scenes on the East and West coasts. I will demonstrate how light shows emerged in the early 1960s out of the powerful confluence of new ideas in science and the arts and alternative lifestyles that defined the West Coast counterculture.

Cultural Origins

West Coast light shows grew out of a psychedelic counterculture with complex roots. The multiple cultural trajectories of media, language, popular music, spirituality, consciousness-raising, environmentalism, and the human body came together at the Ground Zero of the counterculture, San Francisco, and helped form the aesthetics of light shows. Seattle writer Tom Robbins, as a local arts reporter, described light shows in terms of their relationship to the physics of light, reflecting the art world’s awareness of new scientific knowledge and ideas such as Norbert Wiener’s cybernetic systems linking man and machines. He wrote that a light show is “where the Illustrious Buddha arm-wrestles with Thomas Edison while Albert Einstein keeps score…. Along with symbols, sounds, colors and iridescences of varying intensities, the dancer-spectators are stuffed into a boundless amorphous sausage of total perceptual experience, where they are reminded a thousand times a second that all of matter - including man - is merely slowed-down light.”2

Media writer Gene Youngblood, in his seminal book Expanded Cinema, focused on the phenomenon of collective consciousness-raising and the development of a new language that happens during a light show performance. He wrote “In real-time multiple-projection, cinema becomes a performing art: the phenomenon of image-projection itself becomes the ‘subject’ of the performance and in a very real sense the medium is the message. But multiple-projection lumia art is more significant as a paradigm for an entirely different kind of audio-visual experience, a tribal language that expresses not ideas but a collective group consciousness.”3

A Brief History of U.S. West Coast Light Shows

According to Haight-Ashbury historian Charles Perry, light shows were “discovered” in 1952 by a San Francisco State College art professor named Seymour Locks who wanted to revive the Futurist theater experiments from the twenties that used projected images on scrims with live dancers and performers. Locks experimented with Viewgraph overhead projectors, where he found that paints could be stirred, swirled and otherwise manipulated in a glass dish with slightly raised edges to keep the liquid from spilling.4

One of Locks’ students, Elias Romero, became the early Johnny Appleseed of light shows. As San Francisco’s beat movement transformed into psychedelia, Romero took his projection ideas and used them within this new context. Romero would use liquid projections and film to create an environment for poets, dancers and other performers. Together with Bill Ham, his landlord who was an abstract expressionist painter, they are generally recognized as the original creators of the traditional San Francisco light show.

Bill Ham started doing shows similar to Romero’s at the Red Dog Saloon in Silver City, Nevada in 1965, which seems to be the birthplace of the psychedelic music culture. Early bands such as The Charlatans started to dress in 19th century costumes, play long, extended music sets, and create a multimedia music and dance scene that eventually moved back to San Francisco by 1966 with the formation of The Family Dog group of music promoters.6

(Source: Bill Ham Lights)

Along with earlier Vortex light and sound shows presented at the Morrison Planetarium by electronic musician Henry Jacobs and filmmaker Jordan Belson in the late 1950s, early light shows by Locks, Romero and Ham were first presented with experimental music and dancers at the sound artist collective called the San Francisco Tape Music Center. It was founded in the summer of 1962 by Ramon Sender and Morton Subotnik and later occupied a space with Ann Halprin’s Dancers’ Workshop collective and alternative radio station KPFA. This was the epicenter of the West Coast avant garde, with musicians and artists working with dancers, and engineers like Don Buchla creating synthesizers for Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley and Steve Reich. It was also a magnet for New York artists such as John Cage and Merce Cunningham, who performed there regularly.7

Tony Martin was one of the more prolific San Francisco light show artists who also was a painter and Lighting Director for the Tape Music Center. His light show aesthetic exemplifies how artists were being influenced by emerging Chaos theories in physics. He wrote in a recent interview “I find something essential in the flow and interdependency of choice and chance; chaos is comprised of the organized, and vice versa. We live in a dynamic, exciting, joining place. An auditorium, a street corner, a single person and the human condition are one arena: filled with threat and beauty in every instant, and with specific form at every moment.”8

Martin’s light show aesthetic also reflects the progressive environmental ideas of humanity’s interdependency with the natural world that emerged on the West Coast. He talks about his interest in connecting the complex outer world of nature with the equally-complex inner world of mind and emotions, saying “Multiple projection methods gave me new opportunities to explore…my love of natural universal phenomena; illumination of water in motion, whorls of atmosphere in clouds, the startling and inviting forms of flowers…and how humanity fits and doesn’t fit with these.”9

A Los Angeles-based light show group called The Single Wing Turquoise Bird also came out of the rock concert scene, and were prominently featured in Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema. One of its members, Peter Mays, wrote about how working collaboratively with a group created a “collective vision and meaning that’s like Herman Hesse’s idea in ‘The Glass Bead Game’ - taking everything in all cultures and communicating comprehensively on all levels of society simultaneously…Our language definitely is anti-Minimal….We’re making Maximal Art…. It seems that the spirit of Abstract Expressionism has been distilled into a pure form in the light show; sort of carrying on the tradition while at the same time transforming it into something more universal.”10

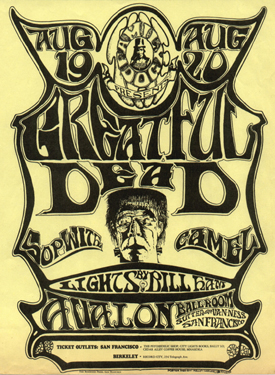

San Francisco light shows also quickly spread to Portland, Seattle and other cities around the world as young artists and other creative types experimented with lights, colored gels, and projected films and slides to accompany touring bands such as the Grateful Dead. In Seattle, two light shows, Lux Sit and Dance and the Union Light Company, exemplified the distinctively different East and West Coast light show aesthetics.

Seattle Light Shows

The first light shows in the Seattle area occurred on November 5, 1966, when KRAB radio held a benefit concert. It was this event that birthed both the Union Light Company and Lux Sit and Dance light shows. Lux Sit and Dance was founded and organized by visual artist Don Paulson in January 1967, taking the name of ‘Lux Sit,’ (Let there be light in Latin) from the University of Washington Seal. Together with Dance, the title’s acronym was LSD.

Paulson had attended Warhol and the Velvet Underground’s first public performance together in New York at the Cinematheque on February 8, 1966. It was a prelude to the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” light show that Warhol toured around the country that featured blinding strobe lights, projected Warhol films, and live music by the Velvet Underground with simulated sadomasochistic rituals performed by Nico, Gerald Malanga and other Factory regulars. Paulson incorporated this “hard edge” East Coast light show aesthetic into Lux, Sit and Dance by using white strobe lights along with colored lights.

In an unpublished manuscript, Paulson described Warhol’s light shows as “outrageous, far from the mellow hippie light show concerts beginning to happen on the west coast. This hard edge, eastern approach to art was the reason San Francisco hated the Velvets and Andy Warhol. Some felt however that the hard edge east coast best reflected the social/political climate of the day and that the San Francisco hip scene was on some kind of fantasy trip and more geared to Folk than Rock.”11

Seattle’s Union Light Company (ULC) consisted of six artists who lived and worked together during the time of the light show’s short run in Seattle and New York City. One of the artists, Carol Burns, had studied to be a documentary filmmaker at Stanford University, where she saw her first light shows in 1965. Their time in Seattle was short, lasting from their first coming-together in late 1966, to summer 1967, when they left Seattle with Country Joe and the Fish to be their light show in New York City. The band was not well received, being too laid-back for New York audiences. But the ULC attracted a true financial angel named Michael Mayerberg, who had also supported off-Broadway Theater of the Absurd productions and Walt Disney. They stayed in a rent-free loft in lower Manhattan and worked with The Group Image that Carol Burns described in 1968 as “a tribe like only New York could produce - they own a club, have their own Band (The Group Image), do commercial advertising for hip Madison Avenue companies, and work with magazines on ‘psychedelic’ layouts.” The ULC soon realized that the World dancehall where they performed was run by the Mafia, and three of the members returned to the Pacific Northwest in late 1968 as the commercialization of the hippie culture ended “the dream.”12

The ULC’s light shows are incredibly dense collages. A recently-produced video recreation of a ULC light show accompaniment to a Country Joe and the Fish song "Superbird" with lyrics about Vietnam and President Johnson going back to his ranch shows images of Johnson’s face superimposed over faces of Vietnamese children. There are also Mickey Mouse cartoons juxtaposed with soldiers marching, collaged together with colored lights and geometric patterns formed by glass plates placed on overhead projectors. These montaged images were manipulated live, by hand, from multiple projectors, and form intense kaleidoscopic effects. At a live presentation at Seattle’s Experience Music Project in 2004, ULC’s Ron McComb sayed they were looking for an antidote to the barrage of mass media images they experienced on TV everyday. Their work exemplifies VanDerBeek’s “new picture language” made to combat the mainstream media messages and help raise the consciousness of the audience.

Conclusion

Forty years later, light shows have remained stuck on the fringes of popular culture and the art world. They represent a unique conjoining of disparate elements that link the worlds of art, science, technology, popular culture, and communication. They are grounded in the psychedelic experience of what Whitney Museum curator Chrissie Iles, and others before her, call synaesthesia, “in which the body is perceived as becoming at one both with others, with the sounds and images experienced, and with the surrounding architectural space.”13 Today we find ourselves in an ever-expanding electronic media form of synaesthesia, where we are increasingly immersed in an aurally and visually saturated media culture that was identified forty years earlier by light show artists.

After the hippie culture was co-opted by mass media attention in the late 1960s, light shows were “electrified” and computerized as mostly ambient lighting effects in disco dancehalls and rock concerts. However, we can see some of the original countercultural intentions re-emerging in the mix culture of DJs and VJs found mostly in urban late-night venues. A light show artist from the 1990s underground Rave culture named Lon Clark wrote “I like to think that the light show I’m doing is not simply guiding a visual experience, but actually filtering through the bog of visual information and remixing it, redirecting it so that we are able to reinterpret and challenge what it is we can actually see. Using slide, film and video projectors, computers and mixers side by side with hand rigged contraptions to alter the light form, we put images into new contexts giving them new meanings, and create a moving collage of patterns and pictures which give us a visual ground to reinterpret our realities.”14

This late 20th century re-emergence of the original intent of light show artists to manipulate and recontextualize images and sound reinforces our ever-increasing need for individual intervention into the pervasive forces of mostly commercially-driven mediated messages. I believe that West Coast light shows represent a significant multimedia folk art form that was the primitive beginnings of ever-increasing attempts by artists to master the ever-expanding mix of 20th century communications media technologies in order to raise the collective consciousness of the audience rather than sell them something. Light shows just might be the beginnings of what filmmaker Jonas Mekas, in his 1964 Village Voice article, called “the absolute cinema, the cinema of our mind.”15 They can begin to show us how to tune in to the powerful forces of change and chaos by making them visible from the inside of what Tony Martin calls a “dynamic…joining place” of heightened inner awareness that connects to the universe. They might just show us how to begin to speak VanDerBeek’s picture language in order to help transform our collective awareness and begin to reverse the destructive forces threatening our civilization and our planet.

1. Stan VanDerBeek, Culture: Intercom Manifesto, 1965

2. Tom Robbins, Seattle newspaper, 1965

3. Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1970) p. 387

4. Charles Perry, The Haight-Ashbury: A History (New York: Random House, 1984) p. 37.

5. Ibid., p. 39.

6. Ibid., p. 9.

7. Bernstein, D., editor, The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde (Berkeley and LA, U. of CA Press, 2008).

8. Tony Martin, “Composing with Light,” in The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde (Berkeley and LA, U. of CA Press, 2008), p. 145.

9. Ibid, p. 145.

10. Youngblood, p. 398.

11. Don Paulson, unpublished manuscript, 2001.

12. Based on author’s interviews with Carol Burns and Ron McComb, 2000-1.

13. Chrissie Iles, “Liquid Dreams,” from Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era catalogue edited by Grunenberg (London: Tate Publishing, 2005), p. 70.

14. Lon Clark, Power to the Pupil (San Francisco: xlr8r magazine, 2001).

15. Jonas Mekas, Movie Journal (N.Y, MacMillan, 1972), p. 146

Robin Oppenheimer is an internationally-recognized media arts consultant and scholar who has worked in the field since 1980. She was the Executive Director of 911 Media Arts Center in Seattle and IMAGE Film/Video Center in Atlanta, where she also directed the Atlanta Film & Video Festival. In addition, she has produced numerous large-scale media arts projects, curated video art exhibitions and festivals, and written about the media arts. As the first (and only) Media-Arts-Historian-In-Residence at the Bellevue Art Museum in 2000-02, she researched and produced an exhibition about the history of the experimental Bellevue Film Festival (1967-81). She also researched and helped produce the Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) Reunion Symposium at the University of Washington in 2002. Based in Seattle, she is a Lecturer in the Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences program at the University of Washington Bothell campus. She is also a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Interactive Arts and Technology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, where she is researching the historic creative collaborations between artists and engineers in the 1966 “9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering”.