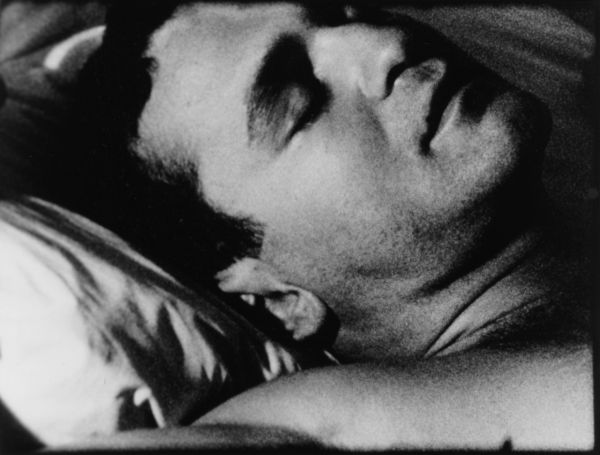

Andy Warhol, Sleep (1963).

Labor Day is supposed to be a day that honors those of us who work for a living with an extra day of rest. I'm writing this on Labor Day, at home on my own laptop, avoiding a long list of other tasks I need to attend to in order to keep my work, and my life, manageable. That work happens all the time and increasingly also at the worker's own expense isn't news, but it helps bring into sharp, urgent focus the arguments in Jonathan Crary's terse, polemical new book, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep.

Instead of focusing on labor, Crary takes sleep as a lens through which to consider economic and social transformations wrought by late 20th and early 21st century techno-global capitalism. Offering a genealogical account of the reformatting of time from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution to the present, 24/7 is relentlessly negative: sleep is the last unleveraged form of human activity and it is violently threatened by a world in which the divisions between night and day, between rest and work, are disappearing due to mutations in the experience of time produced by unceasing digital networks, new metrics for productivity, and ever-expanding forms of control and surveillance.

Opening with chilling descriptions of contemporary military-industrial research on how soldiers might function without sleep and torture techniques based on sleep deprivation, the book quickly establishes sleep as an activity that is constitutive of human life at a basic level.[i] That sleep is threatened not just in extreme situations but in the realm of everyday existence has to do with what Crary describes as "a generalized inscription of human life into duration without breaks, defined by a principle of continuous functioning. It is a time that no longer passes, beyond clock time." As he elaborates the specific textures (or lack thereof) of this new temporality, signaled with the shorthand 24/7, Crary ties the disruption of sleep to an emerging and intensifying set of demands around our productivity as workers. More than simply an elaboration of Marxist theories of modernity that hinge on new concepts of space and time (think of the work of Fredric Jameson, Ernst Mandel, E.P. Thompson, among others), 24/7 seeks to specify how an increasingly homogenous construction of time reorients human activities and experience, and is thus transforming us from the inside out.

GIF by Zoe Burnett.

In part, this new uninflected temporality is tied to the constant illumination of screens through which we are connected, regardless of what we are actually doing, to mechanisms of surveillance and algorithms that continually serve us more of what we have revealed that we "like." For anyone familiar with Crary's work on vision and attention in modern culture, this argument comes as no surprise. But 24/7 has a broader scope, arguing that visual experience and its function within digital culture are far overshadowed by other kinds of sensations and activities. Key concepts here are self-management—the way that we willingly, even eagerly participate in producing profits for multinational corporations and in state surveillance via products like Facebook and Gmail—and a continual cycle of consumption as production—in which our productivity as workers relies on our consumption of commodities from smartphones to streaming movies to (mostly useless) information itself.

The smartphone in particular exemplifies Crary's understanding of the economic and social reorganization that has taken place over the past three decades, often referred to as neoliberalism. It represents two seemingly opposed tendencies: on the one hand, there is the standardization of experience and mass synchronization, and on the other, "the parcellization and fragmentation of shared zones of experience into fabricated microworlds of affects and symbols." This apparent contradiction is key for understanding the particular impossibility of the current state of technological experience: we might all be doing the same thing (looking at our own individual screens, typing and swiping), but the effect is increasing separation and irreversible damage to any kind of collective experience.

Zoe Burnett, Life. Animated GIF.

It is worth attending to how carefully Crary demarcates this contemporary regime of experience. Nearly twenty-five years ago, in his first book Techniques of the Observer, he argued that with industrial reorganization and scientific studies of perception in the middle of the 19th century, the camera obscura, which had functioned as a model for human vision for centuries, was surpassed by a new regime of vision based on the perceptual apparatus of the human body itself. Now he eschews such epistemic breaks based in scientific and technological discourse, positing instead that we need to focus on paradigms of experience and perception.

[I]t must be emphasized that we are not… simply passing from one dominant arrangement of machinic and discursive systems to another. That books and essays written on ‘new media’ only five years ago are already outdated is particularly telling, and anything written with the same goal today will become dated in far less time. At present, the particular operation and effects of specific new machines or networks are less important than how the rhythms, speeds, and formats of accelerated and intensified consumption are reshaping experience and perception."

There is a challenge here (of no small relevance to Rhizome itself) to theories of "new media" that focus on technical or aesthetic mutations rather than addressing the modes of attention and cognition demanded by digital devices and formats in general. By turning exclusively to a theory of the user and leaving behind a certain materialist inquiry, Crary never explicitly considers those affected by contemporary technology who aren’t its intended consumers, such as victims of drone strikes, soldiers fighting to control the supply of coltan, or workers in smartphone sweatshops, implying simply that indifference and lack of attention to these positions is yet another effect of the dull sameness of 24/7 time. Still, Crary’s provocation is certainly a useful reminder of the fact that perceptual paradigms extend well beyond any specific technology.

In particular, this argument is useful in articulating the possibilities of resistance for those embedded in the 24/7 experiential regime. As in his other work as art historian, Crary develops such arguments through a rigorous mix of Marxist analysis, Foucauldian histories of power and institutions, and a commitment to a Situationist tactics and aesthetics. A kernel of 24/7 appears in Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture (1999), where he argues that in the late 19th century,

…spectacular culture is not founded on the necessity of making a subject see, but rather on strategies in which individuals are isolated, separated, and inhabit time as disempowered. Likewise, counter-forms of attention are neither exclusively nor essentially visual but rather constituted as other temporalities and cognitive states, such as those in trance or reverie.

Now, more than a decade later, Crary laments the disappearance of many of these "counter-strategies" found in seemingly non-attentive states (i.e. dreams and sleep) with the intensification of spectacular culture wrought by digital technologies, such as the personal computer and the Internet.

.gif)

Cory Arcangel and Paul B. Davis (Beige). Naptime (2003). GIF extract of bootleg YouTube video. Credit information via New Museum.

Although Crary concludes with sleep as a site of potential collective resistance (one that, it should be said, may have already become impossible) his initial interest in sleep as a basic requirement of human life is suggestive of other potential political and social connections. By focusing his concerns in 24/7 not only on new modes of production (i.e. new technologies and the kinds of labor they solicit from users), but also on reproduction (i.e. sleep as a necessary rest and resetting of the body), Crary approaches a particular strain of Marxist feminist thinking that emerged in the 1970s and has recently become celebrated in the theoretical discussions surrounding Occupy Wall Street and activist challenges to contemporary capitalism. The economics of social reproduction have been a central concern of thinkers like the Italian Silvia Federici and the American Nancy Fraser, among others. Although he does not cite or acknowledge these thinkers or their arguments, Crary’s concern with the obliteration of affective dimensions of human life – not just sleep and reverie, but also questions of care and empathy that once grounded collective social welfare – by techno-capitalism has everything to with the fact that, as Federici articulates, affective labor has been generally excluded from the market because it has been feminized and thus undervalued or simply appropriated. The dream states championed by Crary should be considered part of this broader category of affective labor. This categorization is partly biological—while one sleeps and dreams, the body and mind are recharged—but it is also social—think of the sleepless state of new parents as they adjust their own cycles of waking to care for an infant before soothing the child back to sleep.

Seen in this light, the penetration of capitalism into the realm of sleep is one aspect of a broader issue. Just as there is no longer a separation between work and leisure and between night and day, there is no longer a separation between wage-earning work (traditionally marked as male) and work traditionally coded as female, such as caring for loved ones. Nancy Fraser characterizes this as a new emphasis on the "family wage," in which women’s paid and unpaid labor are both necessary to basic survival in post-welfare state economies. Crary is right to be anxious about the rise of 24/7 culture and the loss of sleeping and dream life, but his exclusive emphasis on individualized forms of perception and experience can too easily exclude other new mutations in capitalism’s ongoing colonization of human life.

Drop City.

It is perhaps telling that Crary devotes a great deal of space in 24/7 to the argument that 1960s counterculture posed such a significant threat to capitalism that 1980s neoliberalism was an aggressive and successful attempt to quash it. The experience of living in utopian countercultural communities, such as Drop City, was not liberatory for many women, who found themselves tasked with the work of cooking and childcare, to say nothing of dealing with the welfare office, while their male counterparts made art. Instead of continuing to mourn the losses of the 1960s, isn’t it time for new strategies? How might we think about living through this period of capitalism such that the value of all forms of affective labor is not only understood, but preserved (or salvaged) from the assignment of a dollar value by the market? In part, this requires that we attend more carefully to how neoliberalism has been exploiting differences, not simply making us all more the same.

[i] In a more banal example of the contemporary state of sleep, the Well blog on the New York Times recently published an article about new studies showing that people have less self control and tended to eat more and unhealthier foods when they are sleep deprived. "The relationship between sleep loss and weight gain is a strong one, borne out in a variety of studies over the years," the author announces, citing statistics and experts, but particularly the most recent research in which the effects of sleep deprivation were measured through brain activity. The conclusion: sleep "[is] the single most effective thing people can do every day to reset their brain and body health." This conclusion is hardly shocking, but it becomes interesting in contrast to the Times recent attention to the increasingly brutal schedules of the working poor and its rather banal coverage of middle class families learning to turn off their smartphones before dinner. All of which begs an important question: How are our biological rhythms being disrupted and reset by new economic and social imperatives for increasing productivity and the technologies that aid and abet these demands? And how might the correlation between sleep deprivation and mindless consumption play out in other areas of contemporary life?