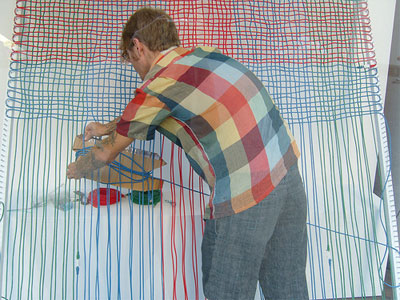

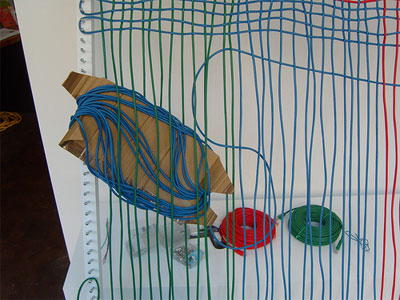

(Photo credit: Travis Meinolf)

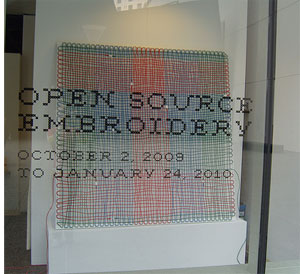

The exhibition “Open Source Embroidery” opens tonight at the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco and it will be on view until January 24, 2010. The show is part of an ongoing project, initiated by Ele Carpenter in 2005, which examines how both embroidery and code can be used as tools in participatory, open source production and distribution models. “Open Source Embroidery” brings together artists, crafters, and programmers to explore this topic in the form of workshops and exhibitions. I spoke to curator Ele Carpenter further about the evolution and multiple realizations of the Open Source Embroidery project. - Ceci Moss

How did your larger research into socially engaged art and new media art evolve into Open Source Embroidery?

Socially engaged art and new media art practices share the language and concepts of social networks, participation and collaboration but they also have distinct histories and operate within very different social spheres. In the world of media arts people have been excited about the potential of the internet to be used to connect communities of interest for a long time. But new media didn’t invent participation; people who work with social networks on the ground already knew how much time and genuine involvement is needed to facilitate meaningful interaction. New media seems to have pulled ‘participation’ into the culture of ‘cool’ technology. But the most radical impact is the politicized culture of digital media testing the legal and ethical frameworks of production and distribution.

I was looking for a way to make tangible some of these ideas: to make visible older forms of collaborative production such as patchwork, and newer collaborative projects such as open source software. I wanted to try and articulate the different ethical aspects of OS through a material form. I was reading Zeros and Ones (Sadie Plant, 1997) and learning HTML. So my first project was to stitch HTML as a way of showing how easy it is: it’s free, it’s simple and it works. Customising a blog can be easy if you know how. But HTML gives you the tools to create your own space on the net, rather than selecting templates. It is the basic building blocks of the web. Back stitch is the best stitch for text because it keeps an even tension, and you don’t need a template. To my surprise craft networks are huge on the web (ravellry, stitch n bitch etc), and smoking seems to have been replaced by knitting as a socially acceptable activity.

You’ve organized Open Source Embroidery within a number of different arts spaces, such as HTTP Gallery in London and HUMLab in Sweden, and I’m wondering how the project has shifted or changed according to those partnerships.

The OSE project is about bringing people together, so each time a workshop or exhibition takes place the concepts explored are configured by the people and the context. At Access Space, the Html Patchwork encouraged an exploration of the gender divide between working with fabric and cables, within a very strict Open Source Software environment. The DIY culture was so strong, everyone just got on with it. The patchwork provided the opportunity for Access Space to expand their network, and make connections between different kinds of art practice and independent culture in the city.

HTTP Gallery presented OSE within the field of Media Arts and gave the project a good web profile. Artists in the UK came to see the exhibition, and I met David Littler and Kate Pemberton there (who are now taking part of the exhibition).

(Source: HTTP Gallery's Open Source Embroidery set on Flickr)

I came to HUMlab at Umeå University because they support interdisciplinary Humanities projects. I ran workshops in the lab, and presented the HUMlab Syjunta exhibition before developing the large-scale show for BildMuseet and MOCFA. I don’t think anyone had made such a physical intervention in the lab before, and it was great to be able to talk about my research ideas with the actual works there on the wall. The exhibition at BildMuseet gave me the opportunity to develop a major art exhibition, collecting together all the different things people had made through workshops, alongside new work by artists. I was delighted to find that Umeå’s bid to be the EU City of Culture in 2014 was based on an ‘Open Source Strategy’. When the Jury came to Umeå in August I took the opportunity to travel with them to map their journey using GPS as part of Southern, Hamilton & St Amand’s artwork Running Stitch. And Umeå won!

Now the exhibition is flying over to the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco (MOCFA). I’m really interested to see how it’s received there. I like the idea of folksonomy, where meta-data classification is defined by ‘folk’ rather than curators. The Internet has enabled folk and amateur communities to network across distance. Folk culture represents a community of interest defined by its users. The principle of openness and interactivity on the net and the question of how to sort and filter data has led to new social forms of taxonomy sometimes called ‘folksonomy’. Social tagging values the ‘amateur’ perspective, not as unprofessional, but as rooted in everyday experience. Critical Art Ensemble (2005) also values the role of the amateur as a radical interventionist, respecting the relationship between amateur and expert.

(At MOCFA artist Michele Pred will be giving a talk about her work using 2D barcodes, and Action Weaver Travis Meinolf will be weaving a network cable for the window.)

(Photo of installation)

When working with these different organizations, have you found that the audience for Open Source Embroidery has shifted as well?

The OSE workshops are aimed at people with craft of programming and / or HTML skills to come together and explore the ethics and principles of their practice. They are invited and encouraged to make new pieces of code, scripts, knitting, patchwork, weaving, informed by our conversations. In most situations, there isn’t much concern for what is ‘Art’ or not. People who knit or code get involved fairly quickly. People who aren’t involved in either activity are often a bit confused, and it takes awhile to unpack the ideas involved in the production process. But like any art form, the work requires time and thought, and some contextual knowledge, to engage with the whole experience of viewing.

You discuss the possibility of "open source curating" on your blog. I am wondering if you can elaborate, for our readers, how you understand “open source curating” and if your experience with Open Source Embroidery has lead you to consider new curatorial models that might fall under this category.

My blog post tries to describe some of the complex issues involved in the idea of ‘open source curating’. In many ways, there is no such thing. There are just different approaches to negotiating the relationships between artist, curator, participant, intern, maker, crafter, technician, audience, etc.

We often think of curating as ‘selection’ of artwork, but it really includes a process of research and contextualizing artwork within a public space and within a group of people. For me, the OSE workshops are part of the curatorial research process. I have to make sure the concept works in practice. That is to say, the practitioners in the field have to make sense of the interdisciplinary relationship otherwise it’s meaningless. I’m not a programmer or a crafter, but I collaborate with people to make new things from our conversations.

My approach to curating OSE has purposefully included works by people who took part in OSE workshops alongside established artists. I’m inspired by Critical Art Ensemble’s discussion of the importance of the relationship between expert and amateur knowledge (Critical Art Ensemble, 2005 and 2001). So I didn’t want to create a Folk Archive, like Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane (Deller & Kane, 2005), which is a general collection of folk production. Instead I wanted to create a space where both the expert and the amateur could come together within a critical context. Many of the artists have facilitated collective projects, so the distinctions become a bit arbitrary.

References

Critical Art Ensemble, (2005) “The Amateur.” In: Nato Thompson The Interventionists: User’s Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life. Massachusetts: Mass MoCA. 147.

Critical Art Ensemble (2001). Digital Resistance: Explorations in Tactical Media. New York: Autonomedia.

Deller, Jeremy,. and Alan Kane (2005) Folk Archive: Contemporary Popular Art from the UK. London: Bookworks.