This interview accompanies the presentation of Mongrel's Blacklash and Heritage Gold as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

The collective Mongrel emerged out of Artec, a London art and technology space which specialized in providing access to technology training to the long term unemployed in the mid-1990s. Graham Harwood, Richard Pierre-Davis, Mervin Jarman, and Matsuko Yokokoji, Mongrel’s co-founders, employed digital media and the internet as platforms for socio-political and cultural critique, directly addressing racism in the virtual and physical realms.

Matsuko Yokokoji's vital role can only be hinted at in this interview, as she was not able to contribute. Also absent is Mervin Jarman, who passed away in 2014. This leaves the voices of Graham Harwood and Richard Pierre-Davis to discuss Mongrel.

Simone Krug: You were all trying to shift away from the corporatization and emphasis on industry of Artec, while also mimicking its inclusivity. How did Mongrel become a collective?

Graham Harwood: I was teaching a course for the long term unemployed at Artec, but a large part of the intake would have been people that had graduated before but needed reskilling in digital technologies. My task was to widen the access, which I did by attempting to invert the whole thing so we had no one there who had ever done a degree. Because Artec was European funded, we had a really good sum of money to spend on each particular person. We paid them money for training, childcare, and meals and we had them for nine months of learning multi-media skills. It was really influenced by a young group of black artists who had helped found the space, so it was a colored as an inclusive space. It was a place where we could bring in a whole different jumble or mix of people and because we had such great facilities, we could give someone the kind of skills you couldn’t gain on a degree course in a year. Many ended up working for big media companies in London. There was also a whole group that didn’t want to go into industry, who had cultural or political concerns that couldn’t be met in a more corporate environment. That group decided they wanted to continue with their own kind of cultural mix. Mongrel grew out of that, centered around the personality of Richard Pierre-Davis.

Flyer from Artec, 1996-1997

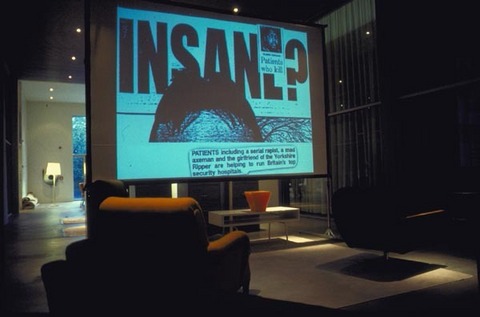

Richard Pierre-Davis: Mervin Jarman and I were students at Artec where Graham was the lead course tutor. While Graham was still teaching I got involved with his project Rehearsal of Memory (1995), a CD-ROM that evolved into an interactive installation that told the stories of high profile inmates at Ashworth, a maximum-security institution. I project managed the project working as the producer and helped elevate it from a prototype to a full-blown finished CD-ROM and interactive installation. I managed a team of about sixteen people to produce the final piece. It became very successful and ended up showcasing at the Pompidou, Banff, and all around the world. That’s how we began to work together. I was also the first student to leave Artec and come back as artist in residence. I was a good communicator and knew everyone in Artec and I grew up in the area and knew the local community. For us, we were in thrown into the deep end, coming from street culture and diving straight to the world of high-end digital art. It was a steep learning curve. This was the early stages of the internet and we just went with the flow. We were embraced by the communities that we engaged with, as well, which spanned from Australia to America. That’s always been the main driver for Mongrel, being able to communicate in different spaces, whether it’s digital or reality. Our Mongrel journey really started when working together on Rehearsal Of Memory at Artec and kind of naturally morphed into Mongrel.

Rehearsal of Memory, installation at V2, Rotterdam, 1995.

SK: Did your background have any significance in coming together to form this group? You all came from different places, right?

RPD: Mervin was a Jamaican rudeboy, who had to leave Jamaica and came to London and found himself on the course—he was basically an enforcer for a Jamaican gang and had a very hard upbringing, but he was always very intelligent and politically aware. The whole digital world was completely brand new to both of us, and we were the only two males with Caribbean culture on the course of sixteen students. We bonded on the first day. We both didn’t know anything about computer technology, but we were fast learners. We also identified together because of our Caribbean heritage. I knew more about Mervin’s lifestyle and he was learning all about mine, because I had the advantage of being brought up in London and was fortunate enough to have gone back to my parents’ place of birth, Trinidad, on a number of times in my youth. London is very diverse and I grew up in a Caribbean community anyway. We built a lot of trust over the whole year on the course with Graham also. Mervin left to work for a corporate company but didn’t like it and came back and joined Mongrel. We were a very diverse group with a rich cultural mix. Graham is working-class English, Matsuko is Japanese but had been living in London, Mervin was Afro-Caribbean Jamaican and I am born in London but my roots are Trinidadian, but Indo-Caribbean. So we had the four main racial groups, within Mongrel, and that kind of made us unique and gave us access to diverse communities.

GH: There was a whole mix of people who could be brought into the Mongrel ethos, which came out of a politics of ridicule. The key thing to understand with Mongrel is class culture in the UK and how this acted in London. At that time we had a lot of state housing in London, you had massive mixing up, and while you might hate the smell of your neighbors cooking or shout about the noise they make, you would also help fix their car, carry the shopping up the stairs for someone, and through this sort of exchange end up the same party. There is much more distance between different classes, in terms of health, opportunity, aspiration, the way we grew up—even though there is racism and everything else, but also a sense of ourselves, which was in opposition to boss culture. Race has a different formulation in the UK, it’s probably not the same in the States.

SK: What conceptual tenets united Mongrel as a unit?

GH: I don’t think there was any unity, or any agreement about anything. I don’t think we intended any, I think we actually quite liked arguing and disrupting each other and causing each other problems. Mongrel wasn’t based on a collective idea, I think if we had one idea, it was here comes everybody, and all their malformations. That’s key, the idea that it was based on our differences, us discussing our differences, and finding out most of them were untrue.

SK: So in a sense it was about breaking stereotypes.

GH: There was a key moment 1995 when internet was introduced into the Artec building and people were hyped up, they thought this is going to be the next big thing. And then the students came in they were really demoralized that they couldn’t find anything about Jamaica or about their own backgrounds at all on the net.

RPD: I was doing a lot of searching online in my down time or during my lunchtime, while I was studying, and I noticed at the time that the KKK and the far right were promoting racism online. I found it quite interesting that racists had a huge presence on the web. We was influenced a lot by thinking about how we could combat what was going on at the time.

GH: That group of students immediately started emailing the far right groups offering to redesign their websites. They immediately started to find the humor in the anonymity, taking on these far right groups and playing with it, setting up fake sex sites between races, etc. While there was this hype about the internet, there was nothing for them, so they decided to take the piss out of what there was. That’s a core part of how Mongrel was developing.

SK: So much of your work seems like it was in response to those early internet searches and all of that far right material you found online in the 1990s. How did you communicate with the people who made these racist, right wing websites? Did you ever actually redesign a site? Or was this a gesture towards wasting their time?

RPD: We wanted to wind them up. Telling them that their online presence wasn’t that good and that I could help them do it better and eventually tell them I’m actually not white. That messed with their heads. I would send them emails telling them that I’m a web developer and I would be willing to upgrade their website. All they knew about me is that they’re getting an email from England. I was just opening dialogue so I could abuse them online, just like how they was trying to abuse non-white people on the internet. Our approach was to take the piss out of them. I showed them that at the end of the day your stuff is actually shit and rubbish compared to what we are doing. Who is the superior race? The way I see it, if aliens landed on earth tomorrow, who’s going to deal with them? There’s no such thing as a superior race. Everyone’s got some form of intelligence. We’ve proved once you put together people from different backgrounds they can make creative shit. It’s that simple.

SK: What led you to addresses notions of race as a group? Were there specific problems that you saw in society that you wanted to discuss?

RPD: Growing up in London I went to a predominantly white school, I had people in my class that were in the National Front, an organization similar to the KKK, though not as well developed. Growing up in London in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a lot of racial abuse that I experienced. But there I had friends from all different backgrounds. I had to learn very quickly what you can and can’t do, so I was fully aware of racial tension within my own life as well as the digital environment. That’s why when I realized that you’ve got the National Front, Stormfront, the KKK, and all of these far right groups on the web, and you really don’t have any great Black Panther or pro-black sites or anything of that nature, so you don’t really have that balance. So in these very early days of the internet I thought of the internet as grey, very boring, very slow. I wanted to add a bit of color to it. That’s how we got to looking at the racial aspects of the web and how we could try and make a difference. We was trying to say something, to challenge something and stir things up.

SK: Did the Mongrel group identify as activists or artists or both or neither?

GH: Neither, I think. I mean, everyone made things. Richard was very much engaged with rap culture and gang culture, he had had a lot of friends die in his life and he was responding to that. Mervin came to Britain with nothing. He was doing some video editing and came to Artec from that position. He very much wanted to develop different tools and techniques and take them back to Jamaica. Matsuko was not a part of Artec, she was my partner and she was a researcher for TV companies and got involved with Mongrel, generally organizing and designing everything. Matsuko—being a strong outspoken woman, with communist parents, and coming from Japan—became a mirror to ourselves. She wouldn’t accept any standard tropes about race because she had not inherited them, she needed them explained, and in the explanation she would take them apart. I was very much between art and activism, or anti-art, a pig with his snout in the trough of a vibrant city. All of us were definitely activists but the others wouldn’t necessarily define themselves as that. They were just people reacting to the world around them, I suppose.

SK: Did subversive, underground, or punk art making, publishing and disseminating magazines influence Mongrel and its output? Could you speak about that history and perhaps about the context that Mongrel grew out of and if they are related at all?

GH: There’s a fairly unbroken line from the Dadaists through the Situationists, which historicizes things. Within London there were groups of people who had been squatting since the 1960s and who taught me and Matthew Fuller, one of our collaborators, a lot, but we were also reacting against the ultra-leftist groups that had emerged at that time. Underground, a free London newspaper Matthew and I were involved in, looked at the politics of ridicule because the City of London, the financial district, made more money in one day than the British government in one year. A ridiculous political situation. These ideas were very much the foundations within Mongrel.

RPD: Before people were really hacking, we were just doing shit. I didn’t make BlackLash until around 1998 after I finished my training. That’s why I turned down offers from MTV and stuff like that, because I thought to myself, “Why would I want to work for a company and they just take my ideas, when I could do it myself?” I spent that whole year learning all the latest technology, basically how computers and the internet work, and we just told Artec what we wanted to do. We had the latest Apple Macintosh computers. I started off on a 7600. That was my first Mac computer and it had a dial-up internet connection. So I’ve seen the growth and development of the internet and thought it was shit to be honest. I was from the MTV generation. I was watching “Yo MTV Raps.” I was into hip hop music, I was into street culture. So, once you mixed that up with activism and digital art, everywhere we went we exploded because we were so different from everybody else. We were so unique that people couldn't work us out. We had so many different layers and I could blend into most environments.

SK: In your game BlackLash (1998), part of your broader project National Heritage, spiders shoot at swastikas and KKK hoods and other heavy iconography. You play with some loaded messages. How exactly did you come up with this game?

RPD: BlackLash was modeled on a game called MacAttack, which came as a free CD-ROM with a very popular magazine at the time called Mac User. I thought the game was shit and boring and I thought, how can I make it sexy? Since I was looking at a lot of far right stuff at the time, I thought it would be a great idea to rebrand this game as BlackLash, changing the storyline and making some badass characters. I told Graham what I wanted to do, he hacked all of the code, and I just replaced the icons, sound files, and text. Graham looks at code differently from anyone else. He can copy or edit code, but no one can copy his because he has a touch of dyslexia. I’m not a coder but I knew how it works to make a game, and told him what I wanted to do with BlackLash. So I added my storyline to it and put a little bit of Wu-Tang Clan samples into it. Most of my friends at the time would play games but not think about making their own. I was like a mini-hero to them because they couldn't believe I made a game.

What did these icons replace in Mac Attack?

RPD: MacAttack used basic icons, it was very much a Space Invaders-type of game.

What was the user’s goal in BlackLash?

RPD: The storyline was that you had to fight the racist forces of evil that were trying to kill the main black character with a deadly concoction of AIDS and heroin. It was playing around with imagery of Nazis and Klansmen with cops that even relates to today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Because it had cops beating down an unarmed black male putting a completely radically different spin on the original game.

screenshot from BlackLash.

SK: The notion that cyberspace was race blind is clearly false. Racism is still prevalent on the internet. Can you speak about Natural Selection (1999), your mock internet search engine that dropped into Yahoo and hacked search results if users typed in a racial epithet?

GH: It was Richard and that current group of students who started on their own to take on the racists. A lot of the people that made the different parts of Natural Selection came from that group of students. We all had ideas about how we needed to think about software culture. We could see that software culture was going to become more and more important and how could you actually begin to break it open? How could you reveal what was going on? That’s why a lot of our projects take things apart and remake them, to reveal the underlying conditions of how the software is constructing certain frames with which you view the world.

SK: Were you trying to work against a software culture that didn’t allow space for a multiplicity of subjectivities or voices? Or was it that software culture only gave you certain options or certain narratives?

GH: I think you can step it down a bit. When Microsoft Word came out, suddenly poor people could If you were in the know, you could use those stock templates to do things you couldn’t do before. If you didn’t have enough money for car insurance, you could scan someone else’s, just using Photoshop to retouch in the bits that you needed in order to produce a document for the police. There were lots of “get rounds.” Generally everyone knew that the machinery and the internet was all fairly oppressive, it was all just going to make everything worse. People felt that these technologies were not going to make us all happy and it was not going to be an inclusive new world. It was going to be shit. But there was enough flexibility and disruption within the technologies that we could see that you could play all sorts of new games with the power that flowed through them. As long as they were made reasonably open, you could critique them, understand the nascent software culture, try to open it up, try to allow people to imagine how power could flow differently through them. You could also encourage other formations of power, for people to do things for themselves, encourage people set up their own electronic bulletin boards, people set up their own publishing. With all of these things online, you could see how useful that could be, but you knew really, it was about making your life more tractable. We had no idea of that Californian ideal. There wasn’t any hippieness about it.

SK: So you were trying to disrupt power flows by creating these types of works.

GH: Yes. If you’re seeing a system being introduced, how many different ways can you counter it, disturb it, make turbulence? It’s always like that whenever a new technical object or system is introduced, power never flows in just one direction through it. It’s up to those that can see it, or artists, or people thinking it through, to re-imagine it so others with less time can open it up differently.

SK: That’s a really nice way of putting it.

GH: And also having fun with it. You know it’s coming. You can’t avoid it, or you don't want to become the Unabomber or something. You want to think of more interesting strategies, really, than exploding some humans.

SK: National Heritage (1997-1999), a body of work that encompasses both Heritage Gold and BlackLash, addressed racialization in many forms, as games, websites, publications, street posters, and gallery installations. This work takes on a life beyond the virtual. Could you speak about how you came up with the content and concept for this project and the significance of its various iterations?

GH: National Heritage arose out of a story from one of the people at Artec during a big riot in London around the 1980s/early 1990s. Her big sister came to get her and when she was taking her home she saw this black policeman who was trying to hold back the crowd and all the black people were spitting on him. It was that kind of story that we took up. We started asking other people and we met someone else who had a story of people spitting on the street. We heard a story of someone else who had cat shit thrown at them and they were stabbed for being black. It seemed like there were a whole bunch of these really difficult stories and also really funny and stupid ones. We were trying to think of what kind of frame could we build, what kind of interactive space could we make in which people could position these different narratives. How could we position them in such a way that if someone wanted to just spit on characters and feel powerful in that sense—what would we do with the machine to make that impossible? We would do things like, if people kept agitating the machine, the machine would agitate them back and would become indecipherable and just speed up and things like that. It basically came from a desire to think of frames in which people could add stories and interact with them.

RPD: Because it was such a massive and uncomfortable project, certain institutions were interested in parts of it. It worked great for us, because it was based around some true stories and harsh realities. National Heritage was a massive monster and Heritage Gold was a popular part of it and very important because it was Photoshop hack, but equally important is all four of us who were behind it. Graham was attacked on a number of occasions when he presented National Heritage by one or two members of the audiences. If we presented it together, no one would attack us. I would answer aggressively as you would ask a question.

SK: What did National Heritage look like?

RPD: For National Heritage we did a massive photo shoot of friends, family, and students from Artec all in the same pose. Then we customized all the images to make up Frankenstein characters. Looking at it, you can see elements of me in the brown character, the black character has elements of Mervin, the yellow character has bits of Matsuko, and the white has bits of Graham. We took bits of ourselves and embedded them into the images and then we customized it with all of the other people from our connections. They look like real people but they’re just made up of elements. That’s how Natural Selection was born; we selected our natural friends and family. Once we made the digital images, we then made an interface where you could interact with the characters and where different storylines and narratives around racial issues would emerge. We interviewed people who shared stories about being abused or observing racial abuse. We installed it at De Waag in Amsterdam, at the society for new media. We had three screens on the top floor where you could spit on each character where you have a 90-degree view and the stories would come out at you. We developed project from a digital poster campaign to a full-blown installation.

SK: I’m curious about the technicalities of how this worked. Was it a game?

GH: It was usually presented as three massive screens on different sides of you and then you would stand in the middle of it and these characters’ faces you were looking at would more or less shudder in a kind of nervousness. As you clicked, it would produce the spit, and they would then close their eyes and then tell you their story. As you moved around the screen space, the characters in the flat space would change the masks they were wearing. For example, the black character wears a white mask or a yellow mask or whatever. So every layer of it is a falsification, because none of the characters actually existed and they wear these masks of different colors that don’t exist and then within that there is this realm of telling stories. There’s also lots of stupid stuff about people smelling differently. There’s one story about why this bloke only likes black women because white women smell sour. Really stupid things.

SK: Who was your audience?

RPD: It’s very hard to come talk to us about race if you’ve got a black guy and brown guy who have no qualms about discussing racial issues. You know what I mean? The arty crowd we would often engage with was predominantly a trendy, traditional digital arts crowd—like the Tate Modern audience firing us loaded questions. However, our work speaks for us. I don’t dress up what we were doing, we were very genuine, and people could tell we were the real deal with what we were saying and doing. We performed a series of events at a tactical media event called The Next Five Minutes at De Waag, we were also doing a workshop at the Biljmermer housing project, which is a very mixed, ethnic area in Amsterdam. These were the kinds of diverse, hard-to-reach groups Mongrel was engaging. A lot of our work is based on community involvement so it made total sense for us to run a workshop as part of the tactical media event. What’s the point of going to Amsterdam and doing a project where we try to explain what digital media is without engaging with diverse communities?

SK: User accessibility and access are key here, bringing these ideas to communities beyond the realm of art, which the realm of the digital by its very nature can open up. At the same time, with National Heritage, you’re playing with so much that cannot fly in the same way in the United States, that speaks to a very specific narrative—perhaps the multiculturalism of London or England. This seems to be very much about the idea of discomfort.

GH: It’s about discomfort, but it’s also about laughing at the stupidity. Remember: National Heritage was built for and by communities that had it tough. It’s meant to become funny and stupid; you laugh at—and with—the people’s stories, or you feel sorry for the people in these stories. It’s a mix of that; it’s not dour. Also, when we took it to the Netherlands and to France, there were lots of questions, like they didnThere a really different kind of racialization based on a really different history of colonialization.

SK: But what’s fascinating about the fact that you speak in these terms, like different countries and their different narratives of colonialization or race is that so much of the work that you do exists on the internet, which is actually global. So it’s curious to me that many of the narratives that you were thinking about back in the 1990s or early 2000s were about things that things that seem very decidedly about the multiculturalism of London.

GH: I also think that if you can tell your story—of your house or your street, then some of that might be relevant to someone else. We never professed that it was anything more than for the people who built it, and for the communities that they wanted to engage with. We built the software Nine and Linker, which were ways for people to go on telling their own stories, their own narratives. Mervin went and used this a lot in Jamaica, and generated a lot of interest to set up the container space that he produced. Richard used it a lot with different communities in London. Matsuko and I produced Nine, which we used with the Surinamese community in the Netherlands. From that they were able to tell the story of how they came from Suriname to the Netherlands and then they set up their own cultural institute for it. I think at that time we were interested in how software could create these spaces where people could talk about where they’re from but also use that as a way to make claim or set things up to get money for themselves. There was so much hype around technology, you could kind of hang on the coattails of it and try to get money into interesting spaces.

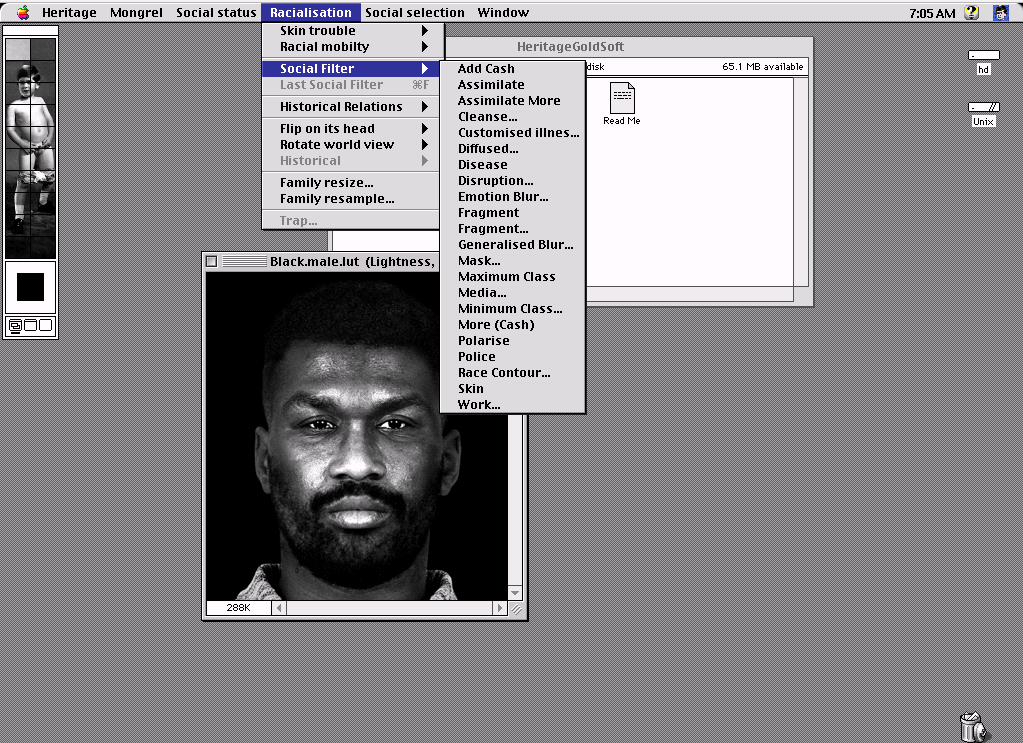

SK: Your work Heritage Gold (1998) is a software modeled on Photoshop 1.0, which you call “the standard heritage editor for all diversity professionals”. In this program, commands range from “monitor racial integration” to “cut skin” or “lynch options” to “define patrimony”. In this software, a user can conceivably fashion a creature (or monster) of their own, replete with a strictly defined bloodline, hair type, and skin color. It’s basically a eugenics program. What kind of questions about identity were you thinking about in creating this software?

screenshot from Heritage Gold.

RPD: Heritage Gold was Graham’s baby just like BlackLash was my baby. Graham was a Photoshop guru at the time. It made total sense to hack Photoshop 1.0 and put our version on it. We thought that the camera was one of the most racist pieces of equipment ever conceived. We thought about how we could mess around with the software and put our ‘mongrelized’ spin on it. We put the Queen of England, Heritage Gold, and a lot of Monty Python type shit into it. Whether you knew Photoshop or just liked the humor, there was a little something for everyone in there. We thought let’s just have fun with this. Photoshop is a very powerful tool, but how can we make it more interesting and funny at the same time?

SK: Who had access to Heritage Gold (1998) and how was it shown?

GH: We were thinking about critique, how software would create different cultural frames. For instance, how would Photoshop create or map of what digital imagery could be, what would happen to the trope of truth in photography? You can think of this as computation being a coherent part of most cultural forms. How could we begin to derive methods for understanding this? People on nettime would download and play with it and comment back about it. So it was kind of a way of beginning to open up a dialogue in that sense. All of these things, all of the Mongrel stuff was happening at different scales, so we would also do workshops with people and give them Heritage Gold to play with as a way of thinking about race, racialization, and what was going on online.

RPD: I’m trying to remember if we had it on a floppy disk or not. I think, yeah, we could have zipped it and e-mailed it to people, because it was 1.0. It was quite small so we could distribute it on a floppy disk or people could download it as a zip file.

SK: How did users react to it?

GH: In the UK, people would laugh about it and then play with it. In a UK setting, people understand satire and irony. They’re kind of like core values. In the States it is so differently charged. It would be a very different thing to play with. People could embarrassingly laugh about it in the Netherlands and in France too, and then play with it and think it through. I imagine it would have been much more difficult in the States. I think it’s much harder in the States because you don’t have the same discourse about class. The spelling for class seems to be R.A.C.E., or at least in my uninformed notion of the States. When we’ve tried to address issues in the USA, it’s been difficult because there seems to be an imagined notion, that the construction of race observed in the USA is a worldview rather than just a unique formulation based on the historiography of one imperialist nation.

SK: In retrospect, what has been misunderstood or misinterpreted or perhaps most contentious about Mongrel’s projects?

GH: I think seeing it from the point of view of the States is a bit of a skewed view. We’ve had a great dialogue with intellectuals in the USA. I’m still not sure quite sure how the work fits into what was going on in the beginning of the internet in the States.

SK: It’s fascinating that you don’t see how the work fits into the American culture surrounding the internet.

GH: There was such a different notion of networks, what was going on with Eastern Europe, you kind of, after the Cold War, how people were using news groups, how people who were squatting were beginning to use the internet. I think there was a different debate in Europe.

SK: So you had a certain freedom, in that sense, making the work you were making from where you were making it.

GH: We had a particular moment, yes.

SK: How has your later work changed? What themes did you start to focus on after Mongrel disbanded? What questions are you thinking about now?

RPD: After Mongrel we all did our own personal projects but remained in contact. I got frustrated of applying for funding for digital art projects. Right now I’ve launched a tech start up called Eco Engine, the first eco-friendly industrial IoE platform. I’m still using all my knowledge and experience from working with Mongrel and pioneering technology and software to develop smart environments to benefit communities around the globe, and now the internet and telecommunications are up to speed for real connectivity.

GH: At the moment, YoHa are doing a project where we are cutting up the rubber boats from the European migrant crisis. The boats are made in China, but they are shipped through Europe because they reach certain safety standards that are designated by European authorities. So, we were in China working with people to cut the boats up and then try to understand it as a technical object. We are not interested in the morality within the migrant crisis, we are trying to understand what kind of power flows—in different directions—through this object, within state actors, outside of state actors, and so now we are doing the same work in Berlin. Our subjects are always roughly similar, it’s just that they move within which technical objects we are working with and in which domain.

So it a sense everyone took those ideas and started doing other things that came out of the ideas of what Mongrel had started?

GH: Yeah. Mervin had always wanted to do the Container Project. He entered into Mongrel always wanting to take something back home so he established the Container Project, that was the core of what he wanted to do. For me I was as interested in constructing software or a critical software culture, which allied with what Matthew wanted. Matsuko was interested in giving visual form to what we were doing. I think everyone took different advantage of it. I think it’s really important that the core people at the beginning of Mongrel took the project in many different directions and they all used it in their own way, I think that’s really important, they all made from it what they did and took it in the direction that they wanted it to go. It moved off in different directions, it didn’t really ever end.

Header image: Mongrel, National Heritage, 1997.