This interview accompanies the presentation of Rent-a-Negro as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Aria Dean: Can you describe what led you to create rent-a-negro.com?

damali ayo art archive: This work was created by the artist to advance the collective cultural intelligence, dialogue, vocabulary, and to encourage questions about race relations. The country was at a third grade level of skills when it came to this topic. This work challenged evolved to get the culture to become something, anything more evolved. It was intended to broach the conversations about race that people were afraid to have. That sounds strange because now everyone wants to talk about race but in 2003 when the work was created, that was not the case. People were still whispering the names of racial groups, like “she’s black” as if it were a disease that should not be spoken aloud. People justified their willful ignorance by declaring a timidity or intimidation to discuss matters of race for fear of being accused of doing it wrong. Humor and the mirror of satire were essential to break these habits.

AD: Can you describe the elements of the project? How did the website and imagined service work?

daaa: The idea was to list the “services” that white people frequently request from black people and put a price tag on them. To draw attention to the feeling of “being on the clock” that so many people in deliberately underrepresented groups feel when they are forced through unsolicited questioning, social demands, educational institutions, awkward interpersonal interactions, and any number of scenarios to educate people and interact with the willful ignorance and laziness of individuals and our collective culture. It made the idea of being in this position akin to being a mechanic, lawyer, or anyone else paid by the hour or retainer for offering expert advice and counsel. It proposed the notion of compensation which raised the question of “for what?” This illuminated that there was a cost to those in the “rental” position which needed to be paid, not by those in the under-understood groups, but by those creating, perpetuating, and enjoying a system in which people are treated as objects and servants.

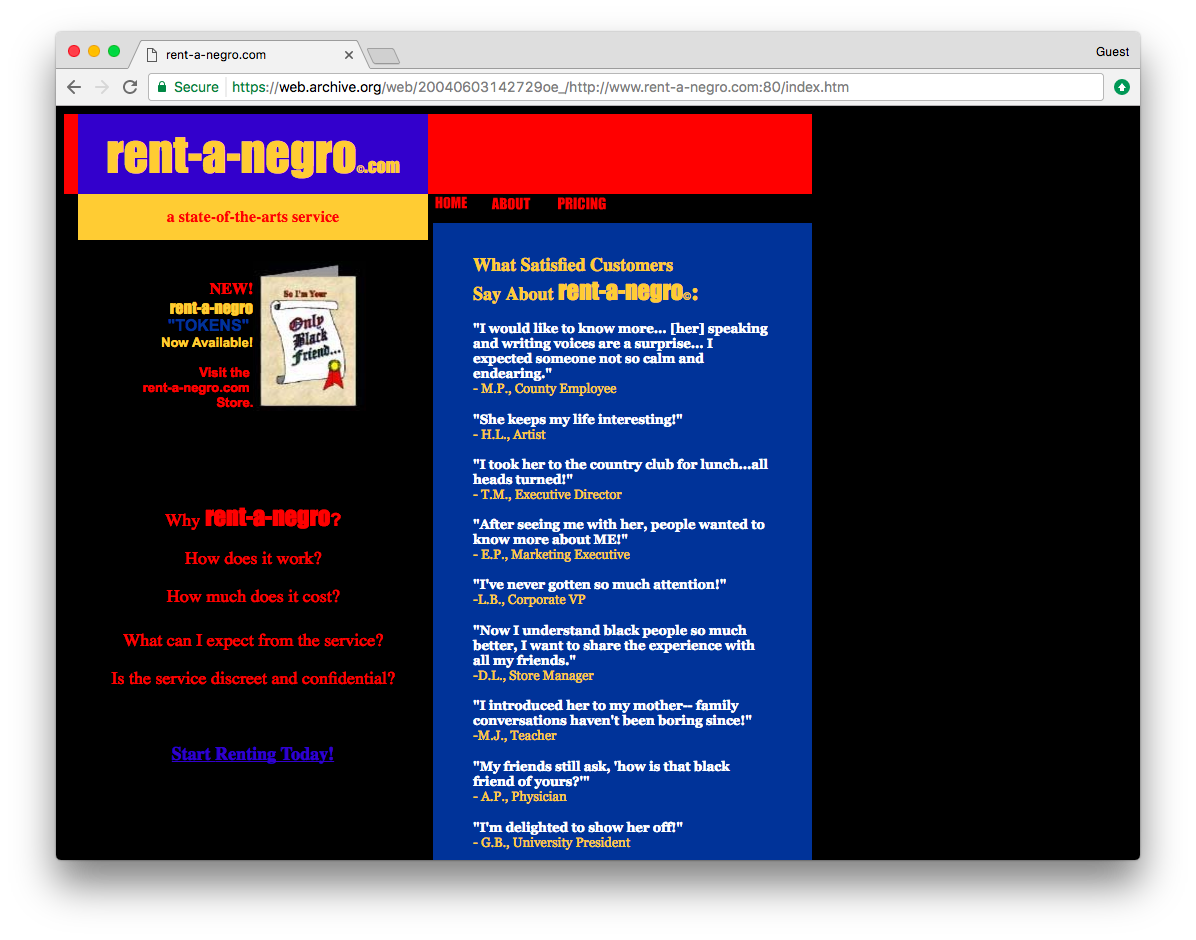

The elements were an interactive web site where a range of frequently requested services were listed with prices, testimonials from satisfied customers, and a rental request form to ask for a black person to come to your event or organization. Everything on the site was taken from actual experiences—the services were all things that black people were frequently asked to do, the testimonials from satisfied customers were all things people had actually said, and the competitive pricing was based on standard fees for professional services.

The follow-up performance work was intended to go on actual live rentals, but once the artist received a request to be used for a gang rape in a town twenty minutes away from where she lived, that idea was sidelined.

AD: Can you tell me about how the project was initially released? How did it disseminate online?

daaa: It was just uploaded to an EarthLink web server. It was never marketed. There was no such thing as social media. It spread by word of mouth. There was a site called memepool.com that picked it up and spread it around. Rhizome was one of the first places to write about it and recognize it as a work of art.

AD: How was the project received when it first came out?

daaa: Droves of emails came in the following categories. Please note this was in 2003 before the ubiquity of social media, trolls, comment threads, the prevalence of blogs, and all the other trappings of the internet. This was in a time when the internet was new and we were just understanding how people use and abuse anonymity. These responses were sent directly to the artist via the website form or sent to her personal account.

- The first rental request that arrived was from Israel, the artist responded affirmatively, but received no reply.

- Rental requests continued, most from the United States. Some were 100% serious. Some were from people trying to be funny. Others threatened to gang-rape the artist, or “rent the negro for a gang rape and then be circle-jerked upon” etc. There were a lot of rental requests that involved being lynched and killed in graphic ways.

- Emails of appreciation from people saying it described their own experience, from Black people but also from Jewish people, Deaf people, and people in wheelchairs.

- Emails from thankful and amused fellow “rentals,” saying “I sent this to all my co-workers, it says everything I wish I could tell them!”

- Emails of hate and anger telling the artist she is ugly, confused, and should be “the first black person lynched by other black people.”

- Emails repeatedly calling the artist a nigger

Other repercussions:

- EarthLink (the webhost) threatened to sue the artist for over-using her transfer allotment

- American Express issued a cease and desist letter to take their logo off the site

- The site had to be re-hosted in a place where it would not be taken down, which meant a hosting service that also supported mediums that the artist was vehemently against (pornography), because they vowed they would defend her right to have the work on the internet.

AD: Can you talk a bit about the project’s posturing and address? In some ways Rent-a-Negro seems to address a white audience. At the very least, it seems to resonate differently for white viewers and black viewers. Can you discuss how the work speaks to its audience?

daaa: The artist has often been accused of addressing white audiences instead of a more inclusive approach, as if addressing the source of an issue is somehow neglecting those impacted by it. This is exemplary of our naive understanding of issues of oppression. The web site was designed to engage “renters” and “rentals” alike. And both groups found powerful identification in both the concept and content.

But audience wasn’t a main factor in the creation of the work. Experience was. The work strove to communicate the experiences of people in marginalized groups by “dramatizing the issue” (one of the twelve principles of nonviolent social change) through a satirical representation of the day to day interactions between black and white people. In simple terms, it aimed simply to tell the truth.

AD: The world now has a much more lively discourse about race than at the time rent-a-negro.com was created, can you comment on this?

daaa: Popular culture’s new fixation on race is fascinating to watch. It’s hip, it’s enlightened, it’s the way to be now. The shallow aspect of that is annoying, but there is real progress—confronting of racism, removal of racist imagery from popular culture, the exposure of the ever-present violence of racism, etc. The ugliness is out in the open where everyone has to deal with it, finally. This is ahead of where we were a decade ago—a step along the path to the vision this work of art held for our species.

There are great people championing this growth, some who were contemporaries of the art and some who are new and adding their own brilliance to the progress. The cultural shifts have momentum and will continue to evolve. Still, the ignorance-turned-obsession with race continues to mean that artists of color are couched primarily in a racial context, yet now this is seen as something liberating or empowering, In truth, it is reductionist, immature, choking, and dangerous. We can be more sophisticated in our understandings of individuals and of art. One day we will be.

AD: Yet instead of engaging this new discourse the creator of rent-a-negro.com has chosen to stop making art and discussing race. Why?

daaa: In 2007 the artist realized she was less and less interested in discussing race. Not only had it begun to bore her, but it was wearing on her mentally and emotionally. Her art-making on the topic had ceased that year, but her career and financial stability were dependent on her continuing to be a spokesperson on the topic, a “professional black person” as she is described on the back of her 2005 book How To Rent a Negro. This is the harsh reality for artists of color who under the regime of visionary limitation (i.e. a culture who needs to see them as what rather than who) they find themselves pigeon-holed into racialized boxes rather than free in the way artists must be in order to thrive. This isn’t unique to artists of color. Our culture is limited in the way it consumes all art—wanting more of the same and being wary of evolution. Yet the pressure to make art about oppression takes a psychological toll on artists of color far beyond that of an artist who is expected to continue to paint landscapes. Art must reflect experience. Race, is only one factor in what generates a person’s experience and although a salient one, certainly not a determinative one. In 2012, she officially took the site rent-a-negro.com offline, and began her transition out of speaking about race. She began to explore other themes far more personal and substantive.

Art eventually became a private practice. Her public works (completed in 2015) are archived on the website damaliayo.com. She does not engage any discussion of race in any way, leaving the room when those conversations arise. True to form, she is years ahead of the culture. Now the cultural conversation, which was so lagging when she created this work, is obsessed with race—and she has moved on.

In describing her choice to move on the artist has sometimes shared a particularly touching story about her work and her journey: Once while giving a lecture to a university audience, the student who gave the introduction said, “damali plants seeds for trees she will never get to sit under.” Afterwards he gave her a drawing of a tree with the words ‘Thanks for the tree.” The artist describes her departure through that touching metaphor, “All I ever wanted was a world where people of color wouldn’t only be seen just as what we are but for who we are. At some point I saw that the seeds I had planted were sprouting stalks and limbs and leaves. It wasn’t an old-growth evergreen yet, but it was enough to provide me a modicum of shelter. Perhaps I would not be denied the chance to benefit from my own work after all. The time has come to let go of doing all the educating and changing the world that was needed to create the breathing room I wanted in order to simply be who I am. I decided it was time—time for me to go sit under my tree.”

AD: Going back to the time the work was made, 2003, after the millennium. What was the relationship to discourse about the internet at the time of Rent-a-Negro’s creation? What was the conversation about the possibilities of the net as it related to identity and race? How did that influence the project?

daaa: Yes, after the millennium but before the robust arrival of the internet as it is in our lives today. At the time there were three other seminal works of satire on the net which this work joined in creating a moment in art history around internet art, satire, and race. The first was Keith Obadike’s Blackness for Sale where he posted his blackness for sale on eBay. Tremendous. The second was blackpeopleloveus.com a humorous site created by two white comedian siblings who playfully exposed our collective ignorance that created tense and awkward racial interactions. Very funny and very popular. The third is less well known because it did not involve race, but it had a direct impact on the creation of rent-a-negro.com. It was a website called “manmeat.com” (that may or may not be the correct name). It was a satirical website selling human flesh as a culinary staple. Nothing short of genius. The site nailed the design aspect and user interface, it was extremely engaging and convincing satire.

The possibilities of the internet were new, fresh, and seemingly unlimited. This was a nascent time of the net, where people were saying, “I’ve just heard of this thing called a ‘blog,’ it stands for web-log.” Things were really new. The site was devised as it was in part because the artist had just recently learned how to code a form in html, and wanted a place to put it into action. Embedding a form on the site where people could actually send in requests to “Rent-a-negro” was as much a result of nerdy code development as it was social change inducing, art-making and boundary-pushing.

There was no intention to create a new art form of race-on-the-net. The art was created simply using the most appropriate medium to talk about a subject that was active and important in the experience of the artist and the world. That’s how conceptual art is made.

AD: Rent-a-Negro is interesting for a number of reasons of course, but in particular because it toggles the relationship between the blackness as object and black people as embodied subjects. Rent-a-Negro’s logic rests on an assumption of blackness as something to be acquired and owned, but also presupposes the emotional and affective labor power of the black person to-be-rented. Can you explain this thinking when it comes to this object/subject relationship?

daaa: “Subjective objectification” was a phrase the artist coined at the time of doing this work. It references the practice of objectifying oneself through the art-making process to illuminate the objectification that others are doing to you. It puts the voice back in the hands of the creator, giving them slightly increased agency over how they are seen, while waking up the lack of sight in those around them. It is beyond the notion of “reclaiming” that we see with slang terms and hateful imagery because it is a direct challenge to those who are enjoying the benefits of living in a world where some are in charge of their own subjectivity and others are cast as objects and servants at the whim of those who enjoy their own agency without a second thought. It raises the question. Can we control how others see us? The answer given is “no, we can’t” but we can make you think twice about what you are really doing. The work all strove to wake people up and see things in ways they had been willfully ignoring. It left viewers no more room for their comfortable denials.

AD: Finally, what was the artist reading around that time?

daaa: The work was directly influenced by Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. Though, I suppose this question aims to elicit a list of resources about race, but that’s exactly the thing—the artist, every artist, every person—is more than that. At the time she was making this work, the artist was most likely, with translating dictionary in hand, clumsily slogging through Samuel Becket’s play Waiting for Godot (En attendant Godot) in the original French.