Commissioned by Rhizome, Jasper Spicero's web-based fiction meltingperson.com (2016) is now showing on the front page of rhizome.org.

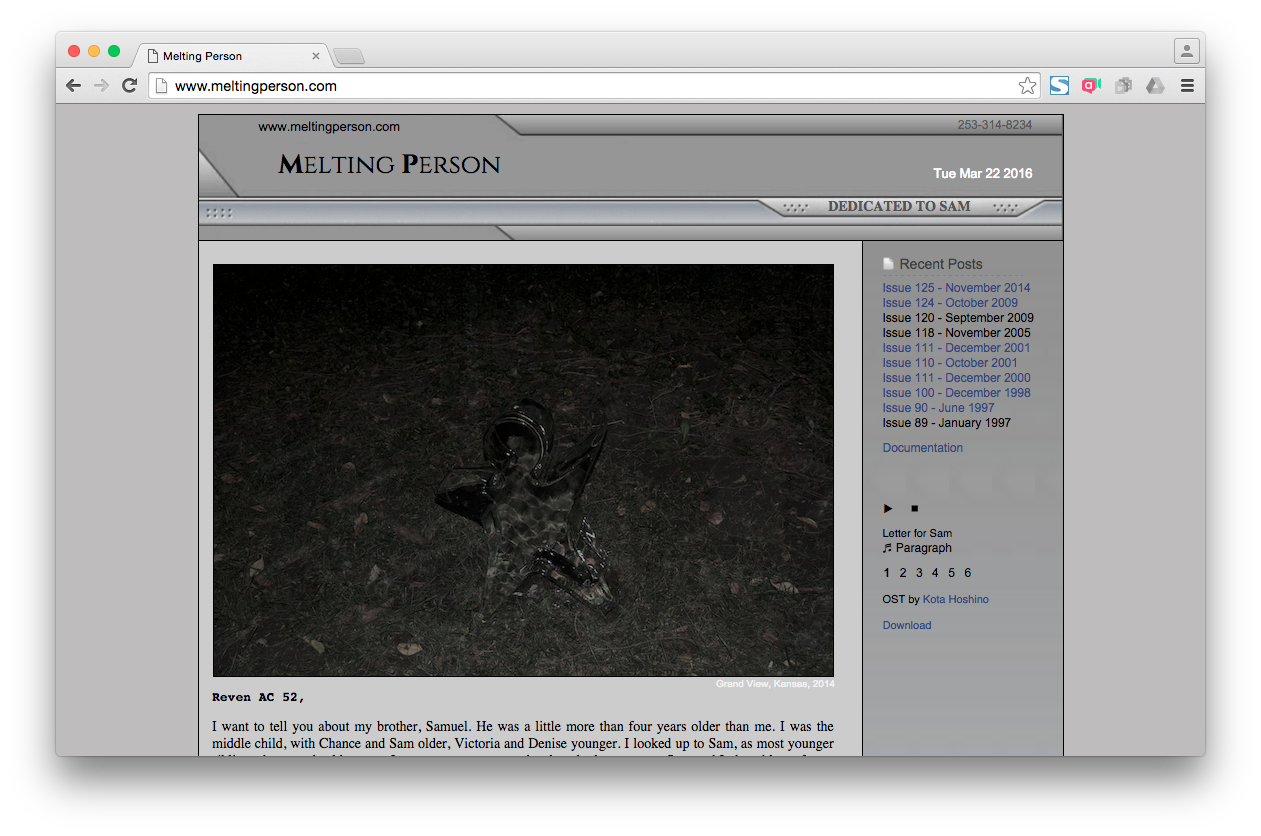

The ice sculpture featured on the meltingperson.com home page resembles a gingerbread figure, except for the two sharp points of its outstretched hands. It's a familiar shape; a web search for “church logo clip art person” or “family logo clip art person” illustrates the widespread use of such figures to convey generic togetherness and joy. Pointy arms also appear regularly on the signage at athletics events, paired with long leaping legs and a slender torso.

The Melting Person is the central visual motif of a body of work by Jasper Spicero that exemplifies his narrative-driven artistic practice. He creates sculptural objects and installations to serve as props and sets for photographs, which are then published as part of expansive web-based fictions.

The latest of these online fictions, meltingperson.com, is loosely modeled after a missing persons database. The site is designed in what feels like a custom WordPress theme, with a metal gray background color and industrial design flourishes that evoke the early 2000s. As in a common blog format, entries are listed on the right-hand side and organized by date, though some appear to be missing.

These entries contain documents that, in Spicero’s words, “piece together a narrative about a missing family member, automotive production, health care, Japanese private detectives and video game development.” They include letters, articles, a screenplay, and a chronology of the first ten years of the Kansas Association of Private Investigators (KAPI). The posts weave together in satisfying ways, but the overall picture feels always just slightly out of reach.

A woman is missing; her car is discovered, submerged. A private investigator becomes convinced that she was murdered by her abusive parents. Later, a letter from the woman emerges, suggesting that she is actually alive and well. Did she fake her own death? Can the date and signature of the letter be trusted?

The woman’s name is Ashlin; her letter is addressed to someone named “Reven AC 52,” and it recounts the story of her brother Sam, explaining his difficulties with alcoholism, his tendency to exaggerate their father’s abusiveness, and his death. Sam died after being run over by twenty-one cars, an almost unbelievably grisly scenario. His body could not be viewed: Was it possible he, too, was still alive?

Along with these documents, meltingperson.com features a full-length original soundtrack by Kota Hoshino, a composer known for his work on videogames such as Armored Core, Evergrace, Echo Night, and Lost Kingdoms. Hoshino is credited on the site; clicking on his name gives a full list of his game composing credits and a Wikipedia-sourced headshot. All of this makes Hoshino seem less like a collaborator than a character within the narrative.

So what does any of this have to do with the Melting Person? The most concrete clue comes in a post dated December 2000: a fragment of screenplay credited to Foy Sledge, founder of the Kansas Association of Private Investigators, bearing the title "Melting Person." The screenplay is set some years in the future, and as a kind of fiction within a fiction, it somehow seems like the most trustworthy account of the events outlined in meltingperson.com. When an unnamed woman throws her dog tags into a river in Sledge's fictional script, this reads as the most authoritative explanation for Ashlin's disappearance.

Another possible explanation: melting. People made of ice have no essence of their own; they are formed by a mold, and held fast in that predetermined shape. As they melt, they take on the shape of their surroundings, and gain the ability to pass through previously impermeable boundaries like fences and grates. The ice sculptures in the “Melting Person” series are often photographed on top of these types of barriers, captured in a moment before they pass through to the other side.

The missing person has already passed through, leaving a gap that engenders an awareness of uncertainty. One of the documents on meltingperson.com includes a grid of indeterminate images of people, their features rendered in a kind of nondescript blur. They function like the child's faces on milk cartons, the AMBER alerts that hit every smartphone in the office at the same time. Are they alive or dead? What happened to them? Might it also happen to us?

Conjuring this uncertainty, the missing person holds narrative completion at bay. The missing person, like the melting person, also resists enclosure.

In Lev Manovich's now-famous formulation, the database and the narrative are competing imaginary forms that structure our world. Database-driven representations are more open-ended and less ordered than narrative ones: "Web sites never have to be complete;" he wrote, "and they rarely are." meltingperson.com can be said to resist narrative ordering in both its form—the database, and its subject matter—missing persons.

Databases are generally associated less with open-endedness than with the muted horrors of bureaucracy, in which the fear and pain and misery of human experience is reduced to data and evidence. In the case of the missing persons database, the incompleteness of the data it contains—the whereabouts and fates of its subjects—is precisely the source of these dark feelings.

But meltingperson.com fills this horror-tinged form with an unsettling sense of longing. In this narrative world, presence may open one up to conflict and abuse, while absence comes across a state of open-ended possibility, a form of escape. Like the AMBER alert and the milk carton photograph, meltingperson.com offers a sense of fascination as well as dread.

Might it also happen to us? Indeed it might.

Rhizome's 2015-2016 commissions are made possible by the Jerome Foundation, Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation, and by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts.