This interview accompanies the Net Art Anthology presentation of work by Mez Breeze.

In 1993, Australian artist and poet Mez Breeze began to develop her own online language, Mezangelle. Her Mezangelle poetry has appeared across the internet over the last two decades under multiple names and connected to multiple avatars.

Mezangelle uses programming language and informal speech to rearrange and dissect standard English, creating new and unexpected meaning. Mez Breeze’s approach to codework—online experimental writing that explores the relationship between machine and human languages—is imbued with a sense of playfulness and creativity.

For Net Art Anthology, Rhizome is presenting 43 emails containing Mez Breeze’s contributions to the net.art email list 7-11, one of the first online communities purely dedicated to net art experimentation. Viewers may subscribe to the email list to receive the works in their inbox one by one over the course of the next year, reperforming their original transmission in the same order and pacing.

The following is an interview with Mez conducted by Rhizome assistant curator Aria Dean in December 2016.

Aria Dean: Can you describe Mezangelle?

Mez Breeze: Mezangelle evolved in the mid-1990s, gestating in email exchanges, computer programming languages + chat-oriented software [ie y-talk, webchat, and IRC] and attempting to fuse English, poetic conventions, programming code, contemporary social commentary, and online communiqué.

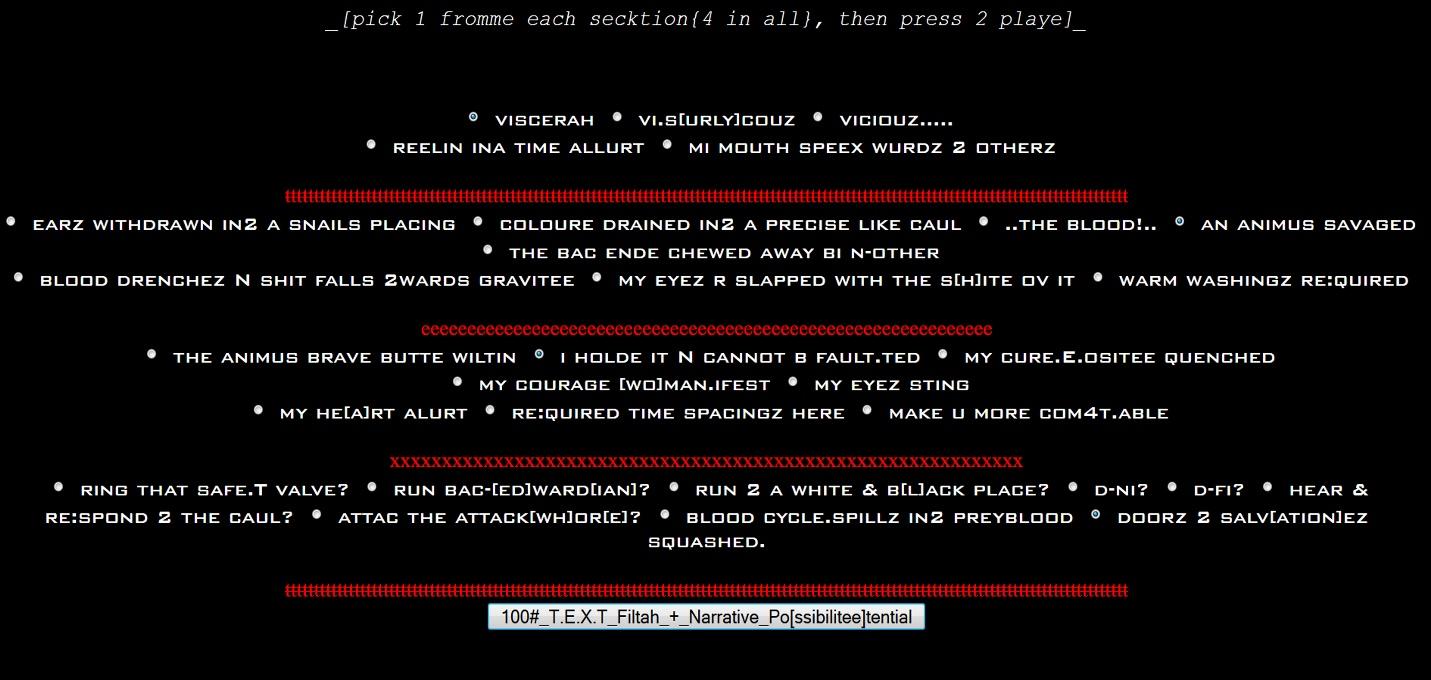

A Mezangelle post on the 7-11 mailing list, 1998

Mezangelle fuels various ongoing codework repositories, one of which is "_cross.ova.ing ][4rm.blog.2.log][_.” The output posted here is constantly evolving and de-evolving in terms of style and convention. Mezangelled works aren't designed to be parsed as linear or static, but instead exist in an artificially induced finishing state:

"Viewers of Mez’s works are not only required to read (and sometimes interact), but to translate the Mezangelle language, which often (if not usually) creates multiple interpretive possibilities. Mez’s interest in playing with—and making as much as she possibly can out of – ASCII code is obvious; the addition of images gives viewers more to work through … Mez works this possibility – with her use of language, and by using images as prefix and suffix—to extreme ends, and by doing so metaphorically hits two, three, or more notes at with a single gathering of letters formed into a word in ways previous generations of writers could not."

—C T Funkhouser in “New Directions in Digital Poetry" referencing the Mezangelle work _ID_xor.cism_

I do see Mezangelle as intrinsically questioning a culture of exclusion that can often develop alongside binary systems, as well as exploring the "rightness" and "wrongness" of function vs. dysfunction, and the binary opposition/conditioning that often envelops those devoted to mono-meaning curves [which in part explains my fascination with trinary logic].

Screenshot from the Javascript-based Mezangelle project “T E X T Filtah”, 2000

While engaging with a Mezangelled text, a reader/user is encouraged to construct meaning in a tumultuous fractured meaning zone that bends and happily shifts comprehension goalposts. Rule-fragments do exist [t]here, but determination of meaning depends on an acknowledgment that there is never only one level of interpretation, or an ultimately correct [or incorrect] option.

Works created in Mezangelle are designed to function, or meaning-establish, via a combination of semantic triggers combined with an individual's own subjective meaning framework. There is no one way to interpret Mezangelle: many people parse only the poetic underpinnings, whereas some in the code-loop happily grok-absorb programming elements or ASCII-like symbols. Many others have analysed Mezangelled works on a more granular level: one of the better-known attempts comes from theorist Florian Cramer, who says of one of my earlier codeworks “_Viro.Logic Condition][ing][ 1.1_ ́ ́:

"What seems like an unreadable mess at first, turns out to be subtle and dense if you read closer. The whole text borrows from conventions of programming languages; it presents itself as a program with a title, version number, main routine—indicated with the line “[b:g:in] ́ ́—and several subroutines or objects (which, like in the programming language Perl, are indicated with two double colons). But the main device are the square brackets which, like in Boolean search expressions, denote that a text can be read in multiple ways. For example, the title reads simultaneously as “Virologic Condition ́ ́, “Virologic Conditioning ́ ́, “Logic Condition ́ ́ and “Logic Conditioning ́ ́. This technique reminds of the portmanteau words of Lewis Carroll and James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake ́ ́, but is reinvented here in the context of net culture and computer programming.

As the four readings of the title tell already, this particular text is about humans and machines and about a sickness condition of both. The square bracket technique is used to keep the attributions ambiguous. For example, the two words in the line “::Art.hro][botic][scopic N.][in][ten][dos][tions:: ́ ́ can be read as “arthroscopic ́ ́ / “art robotic ́ ́ / “Arthrobotic ́ ́ / “horoscopic ́ ́ and “Nintendos ́ ́ / “intentions ́ ́ or “DOS ́ ́. So the machine becomes arthritic, sick with human disease, and the human body becomes infected with a computer virus; in the end, they recover by “code syrup & brooding symbols ́ ́. So mez has taken ASCII Art, as we can see it in the exhibition above, and Net.art code spamming and refined it from pure visual patterns into a rich semantical private language. She calls it Mezangelle which itself is a mez hybrid for her own name and the word “to mangle”…

Since her square bracketed expressions expand into multiple meanings, they are executable, that is, a combinatory source code which generates output. But it’s also a sophisticated reflection of cultural concepts of software which rereads the coding conventions of computer programming languages as semantical language charged with gendered politics. It’s imaginary software which executes in the minds of computer-literate human readers, not unlike the Turing Machine which was an imaginary piece of hardware."

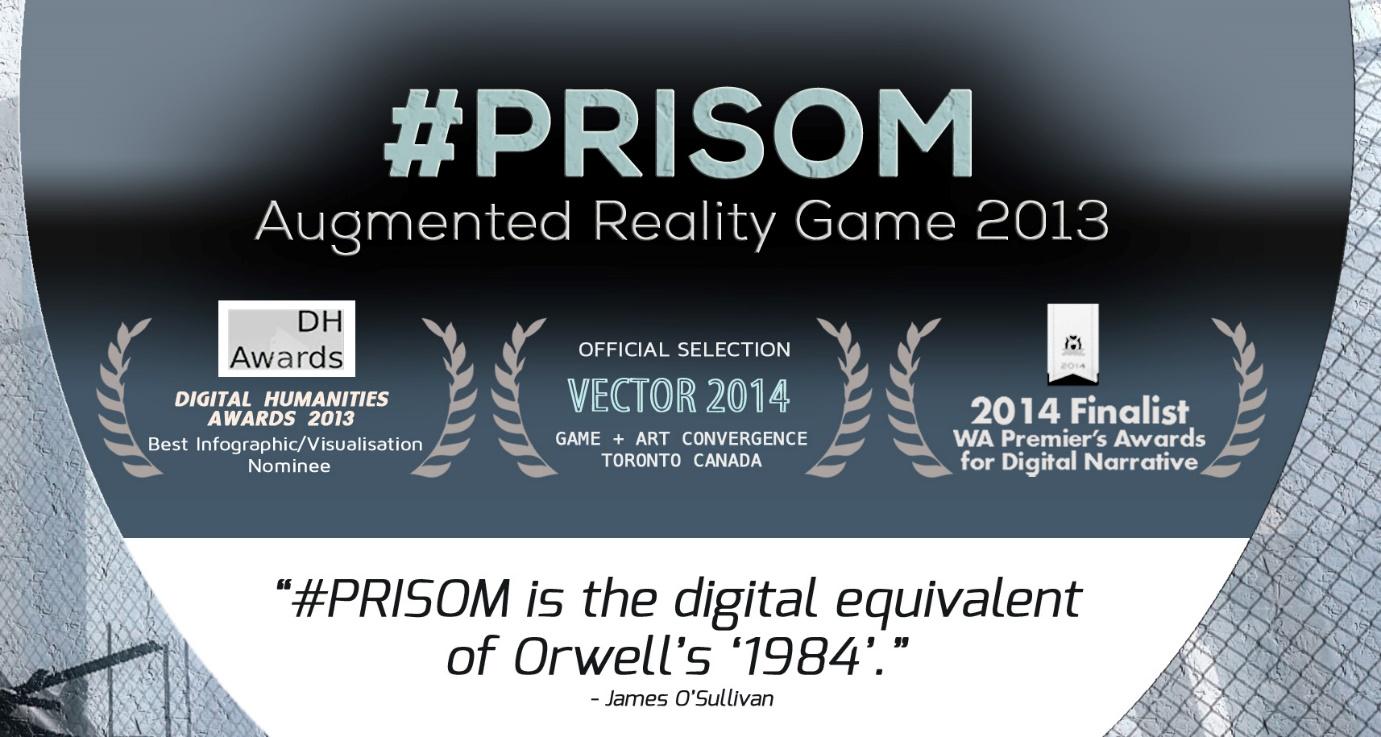

Since 2011, I’ve been pushing Mezangelle into 3D Spaces and mobile apps created by myself and Andy Campbell. For instance, in our anti-surveillance game #PRISOM, the Surveillance Drones “talk” to each other in Mezangelle. "#PRISOM" premièred [via an Augmented Reality Head-Mounted Display set-up] at the 2013 International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, in conjunction with the University of South Australia University's Wearable Computer Lab and the Royal Institution of Australia. When creating the Mezangelle scripts for the #PRISOM Drones, my main influence was global covert surveillance [think: PRISM surveillance program] and increasing monitoring of individual’s private data/lives.

#PRISOM AR game featuring Mezangelle, 2013

AD: Is Mezangelle a language system in the sense that it can be reproduced and replicated by a writer other than yourself?

MB: Indeed it can, and many have produced Mezangelle versions/content of their own [ie Sally Clair Evans, Florian Cramer, Peter Wildman, and Mark Marino’s Netprovs to name a few].

AD: Your poetry is often discussed under the umbrella of “codework,” a form of experimental writing that mixes identifiably human language with code from computer languages. The practices within “codework” vary widely; not all of them engage with and handle code in the same way. While mezangelle language draws on elements of code, the code is non-functional and non-executable, right? Considering this, how do you see the relationship between the code and the text in your work?

MB: I like to think my use of code conventions acts to open up poetic aspects via a type of dimensional interplay [combining the lyrical with a formalised structure]. Those who choose to absorb my output may enjoy trying to ferret out hidden meanings, and/ or derive their own deductions. Some readers that attempt to parse Mezangelle, and codeworks in general, have a certain pre-set programming knowledge that allows for a certain interpretation, whereas some may instead perceive the code interjections as a type of visual accent [especially those who are traditional poetry fans].

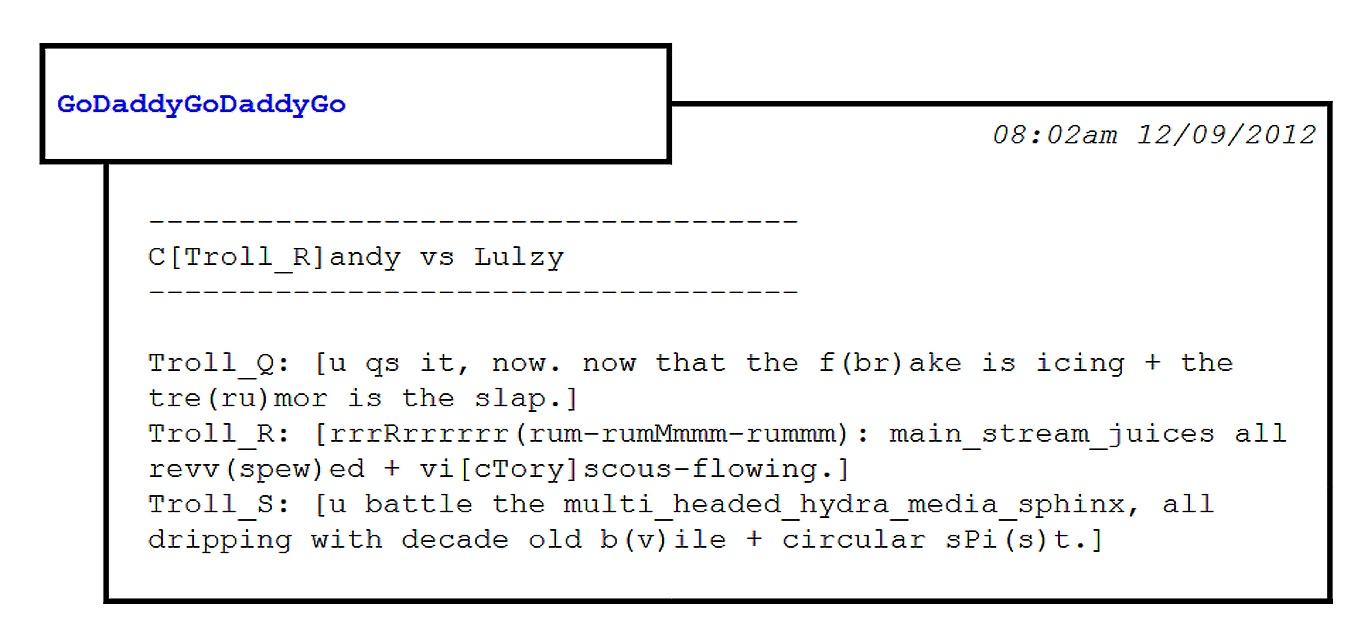

“GoDaddyGoDaddyGo” from _cross.ova.ing ][4rm.blog.2.log][_”, 2012

I do enjoy manipulating standardised code protocols and conventions, and all my works have [at their core] a definitive social commentary function. When creating in Mezangelle, my aim is to encourage continued exploration through code emulation, curiosity, play and repeated questioning/collapsing of institutionalized concepts. Of course, with curiosity and play being strong markers of mine, I do think of my works as cheekily [and sometimes melancholically] subversive.

A more recent analysis by Roopika Risam of the Mezangelled work “Anthropo[S]ceney||AnthropO[bs]cene” seeks to unpack this relationship between code and text:

"Breeze’s use of brackets adds new dimensions and questions to her poem, disrupting both the experience of reading and the possibilities for interpretation. Breeze’s poetry experiments liberally with different dimensions of programming syntax. In contrast to executable code poems, poems that don’t rely on executable code are not bound by the rules that constrain programming languages. Rather, they take advantages of the structures of code to represent the relationship between computational technology and human experience in symbolic ways. In doing so, these poems draw attention to the structural elements of computational technology that we may not see but are central to our experience of technology and of the world."

AD: What compelled you to develop your own online language?

MB: I originally became interested in the idea when, in 1993, I was first exposed to the work of VNS Matrix [who I later wrote about in Switch Magazine and who also feature here in your Net Art Anthology: yay!]. Their mix of game aesthetics, Anarcha-feminism, and virtual/online engagement intrigued me; at the time I was creating mixed-media installations involving painting, computer text and computer hardware. I was also exploring notions of performative identity-play at the time. I first dove online using Telnet/Unix and Kajplats 305 to juggle avatar use, identity-play, and interactive fiction: Mezangelle had its roots here.

AD: What pre-internet literature and language practices were influential in designing Mezangelle?

MB: As I’ve said previously, it’s exceedingly hard to pin down influential content that’s easily reduced to just the literary, so instead I’ll give you a ramshackle list of influences/tools/inspirations [that’s by no means complete]:

- Kimba the White Lion + Astro Boy [manga/anime + not the bastardised Disney versions].

- Two great Hoppers [Grace Hopper, Dennis Hopper].

- David Cronenberg [his earlier visceral works, especially _Dead Ringers_: “gynaecological instruments for operating on mutant women”!!?!].

- Consolidated [specially the album _Friendly Fascism_].

- Giacometti [both Alberto + Diego].

- Horror [j horror, b+z-grade, splatterpunk, Romero, Craven etc – not gorno or torture porn though].

- _New Order_ [before Gillian left (then came back) + the inscriptions on the vinyl I had as a teenager] + _Joy Division_ before them [poor Ian:/].

- MUDS.

- CB Radio.

- _Screamadelica_.

- Dr Who [Tom Baker version(s + jellybeans + the multicoloured scarf!)].

- Frida Kahlo, Sylvia Plath, Virginia Woolf, Stevie Case [for what – in various degrees – to strive for and also what not to become].

- _Ghost in the Shell_ [Originals (1+11)].

- Cindy Sherman.

- Non-Euclidian Geometry [thanks Gina!].

- _Superfriends_.

- John Wyndam [Triffids! Triffids!]

- Snapper [a duck I had when I was about 8?] + Tahnee [a now-passed Border Collie] - both taught me (to) respect].

- Unix [shelled + otherwise].

- Narnia.

- FKA Twigs [Afrofuturism = yaas pls].

- _Porcupine Pie_.

- Altered states of consciousness [in many forms].

- _Nevermind_.

- _Cosmos_ [Carl Sagan].

- _Eat Carpet_.

- The D-Danguage [a made-up language from my teens where my siblings + I conversed via words where we’d replace all the initial letters with the letter “D”].

- _Aeon Flux_ + _The Maxx_ [_MTV oddities_ ftw|wtf!].

- _1984_.

- _The Goodies_.

- Childish Gambino, the Herd, M.I.A, Regurgitator.

- Bill Burroughs.

- Gurrumul Yunupingu.

- ReBirth RB-338.

- _DOOM_ [+ _Quake_].

- Sci-fi + Cyberpunk [specially Le Guin, Ballard, Atwood, Stross, Octavia E. Butler, Bill Gibson].

- LaTeX [+ LaTeX2e].

- _Raw Like Sushi_.

- The Dreamtime.

- Sociology [to that kooky lecturer whose name (but not face) I’ve since forgotten, thanks].

- Koko [the gorilla].

- _G-Force: Battle of the Planets_.

- _The Life of Brian_.

- _Ren & Stimpy_ [“It’s loggg-ogg, logg-ogg, it’s big, it’s heavy, it’s wood!”].

- Dennis Potter [even with the potential misogyny].

- Sam Coleridge [_Kubla Khan_ + _Rhyme of…_, obviously].

- LittleDog + BigDog.

- _The Wizard of Oz_ [original].

- _Sin_.

- Lars von Trier.

- _Jabberwocky_.

- Kathy Acker.

- _Doolittle_.

- Systems Theory.

- _Brazil_.

- _House of Leaves_.

- _True Detective_ [Season 1 only!!!!].

- Brian Aldiss.

- Permaculture.

- _The Canterbury Tales_.

- Max Headroom.

- Adam Jones.

- Hamlet [character].

- Mozilla.

- _ Aenima_.

- Alex the African Grey Parrot.

- _THX 1138_.

- Situationist Internationalists.

- Wakamaru.

- _Phoenix_ + _Frogger_ [+ hours-long arcade gaming at the local takeaway in general when I was 12 (with salty chips, yes please)].

- _Tetsuo_ [1+2].

- ELIZA.

- _Westworld_ [both movie + teev series].

- Theatre of Disco.

- Perl.

- Academia [+ learning the limitations of it].

- Libraries [in all senses of the word].

- _Brave New World_ [novel].

- _The Blair Witch Project_.

- The concept of ARGS [in terms of potentialities rather than necessarily executions].

- David Lynch.

- Peter Greenaway.

- Richard Kelly.

- Python.

- Chris Cunningham.

- Peaches.

- _Duke Nukem[3D]_, _Half-Life[1+ 2]_, Everquest [1 only], _Dear Esther_, _ The Endless Forest_ + _World of Warcraft_.

AD: How do you think digital writing has changed in the last decade or so? Are there new possibilities for experimentation?

MB: Digital writing has transformed in the last decade, absolutely. What’s interesting about this is the altering of social engagement markers in relation to online comms [think: chan/imageboards, txtspeak, memetalk, snowcloning], and how this is shaping discourse in general and the corresponding effects on institutionalised systems [think “fake news” (ie propaganda) items that are in fact a creative (and fundamentally catastrophic) rendering of facts that can alter the trajectory of democracy itself)].

There are many new possibilities for experimentation in the digital writing sphere, including experimentation within game spaces, especially in relation to Virtual Reality/Augmented Reality/Mixed Reality. Potentials include breaking down narratives and distilling and reordering components into discrete fragmented VR units, and/or shifting the story emphasis to consecutive divergings [similar to branching narratives like in Choose Your Own Adventure].

Narrative/VR game “All the Delicate Duplicates” with Mezangelled text splines, 2016-2017

In VR/AR scripting, aspects that previously would have been only been peripheral, or incidental, can now take equal centre-stage: “mono-attentional” entertainment may shift according. Viewers/players will use a combination of renewed agency, 4th wall breakage, and field-of-view-constraint-lifting to accommodate new methods of constructing [story]texts with VR/AR based tools [think: StoryboardVR, Tvori, Mindshow, Actiongram]. The striation between 360 video/photos and "true" [ie agency engaged] VR will [and currently are] reflecting interesting avenues for digital writers.

AD: In addition to disrupting and fragmenting language itself, your work also problematizes authorship. There are a number of different avatars to whom your works are attributed. Is this something that emerged organically in your practice as you’ve created works across multiple platforms and communities? Or is it a more intentional, perhaps even political, choice? Both?

MB: From my POV, my choice to avatar-assign authorship of certain Mezangelled works reflects a desire to meddle with certain systems that influence the formation of meaning, of comprehension. If you systematically obfuscate and deliberately muddy binaries aligned with gender, race, sex, age, ownership, and authorship, your work itself gets an unparalleled chance for interpretation without the looming fact of traditional, and often seductive, polarization, or ego-hinged attribution. So really, my use of multiple avatars is indeed a mix of deliberate crafting and opportunism.