The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

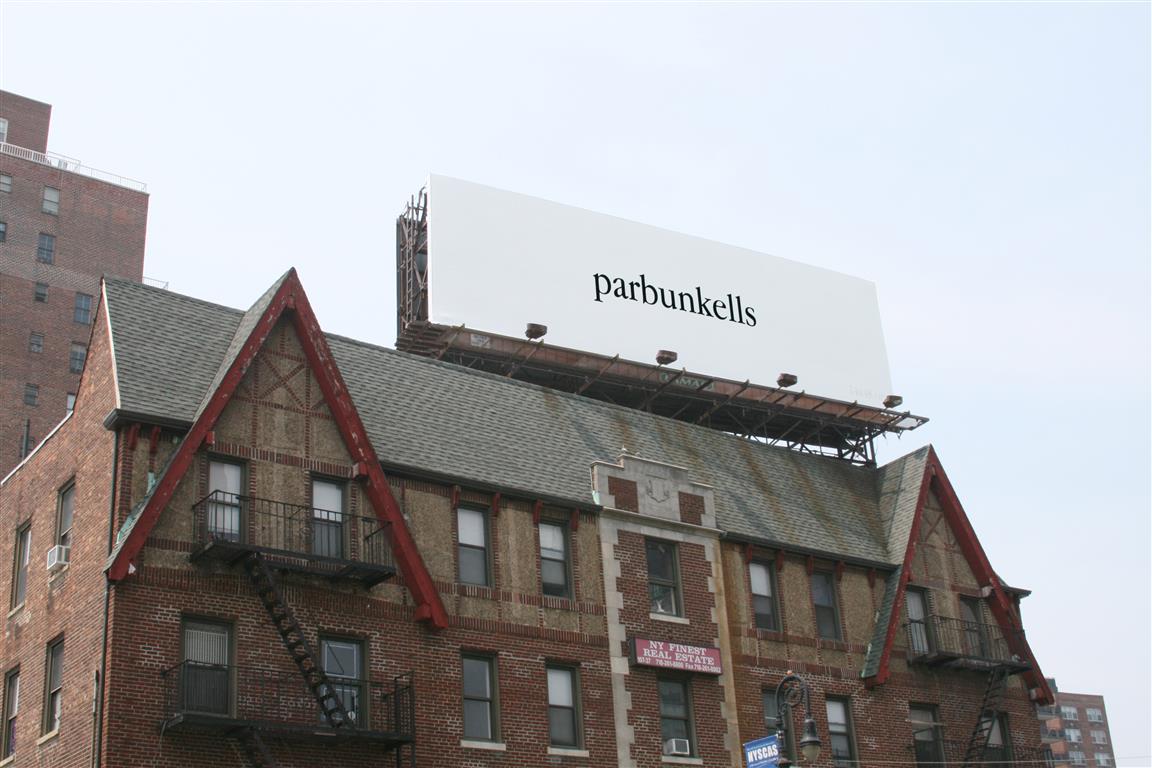

Julia Weist, Reach (2015) at 107-37 Queens Blvd, Forest Hills, New York

Reach, your first public artwork, a billboard produced 14 x 48, is up on Queens Boulevard. Can you talk about that work and your thinking about the connection between public art and the public space online?

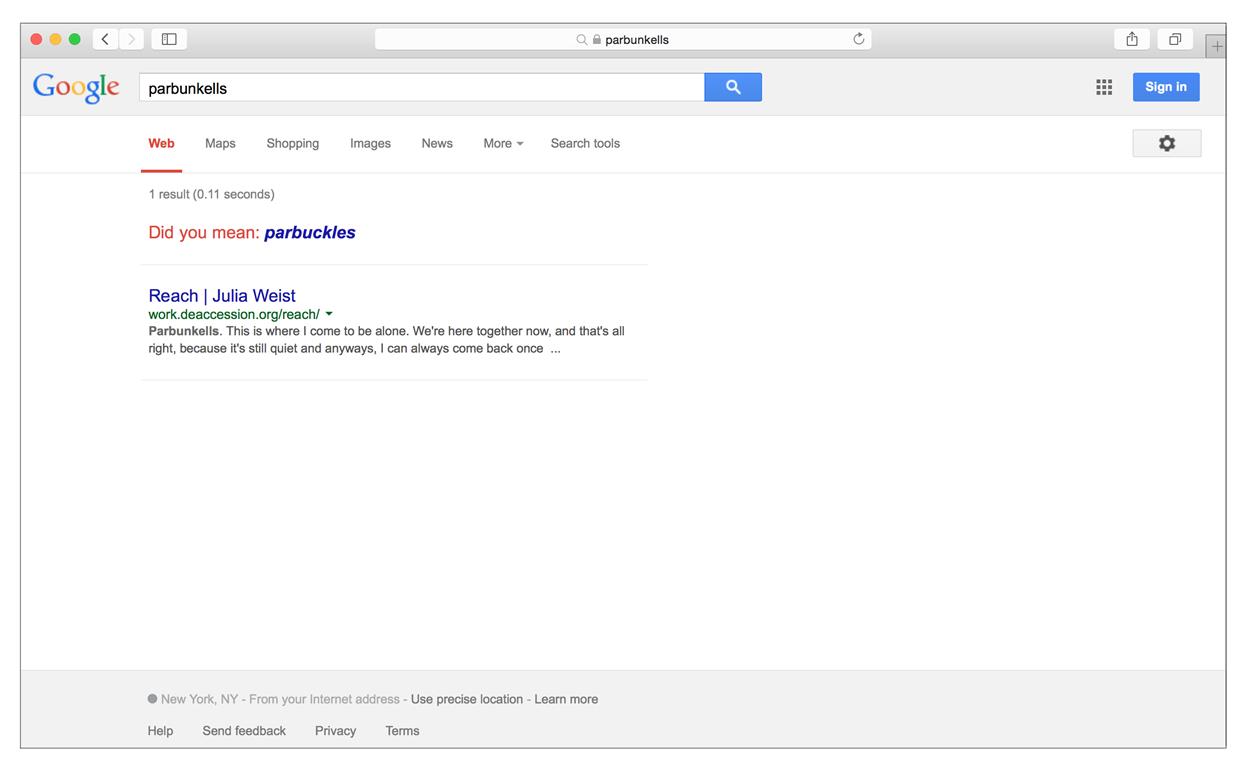

Reach is a billboard featuring an analog word that I made digital. This word was used in print in the 1600s, but rarely since and never online until earlier this year when I created a single search result for it. I worked carefully with Google's Webmaster Search Console to control the crawl and index of a webpage I made, after some missteps with DNS, nav menu, and even permalink indexing that created multiple hits for the word. The Reach webpage includes a short text about the enduring value of emptiness as well as some strong language requesting that no one else use this word anywhere else online.

The project is really an experiment in the viability of singularity on the internet, but also an attempt to render a digital impression physically. When the billboard goes up, I'll plug in a lamp in my home that will turn on each time the webpage is visited (through a series of interconnecting scripts, a circuit board, and an internet-enabled outlet).

We're all pretty familiar with the idea of sharing a lone experience—think a solo hike in the middle of the wilderness—with scores of non-present entities online. But what we're less familiar with is the case where hundreds of thousands of people experience the same thing in real life, but create no shared digital footprint. I'm interested in the fragility of that proposition, and in measuring the project's progress through a domestic indicator.

Screengrab of the Google search result for the Reach project (2015)

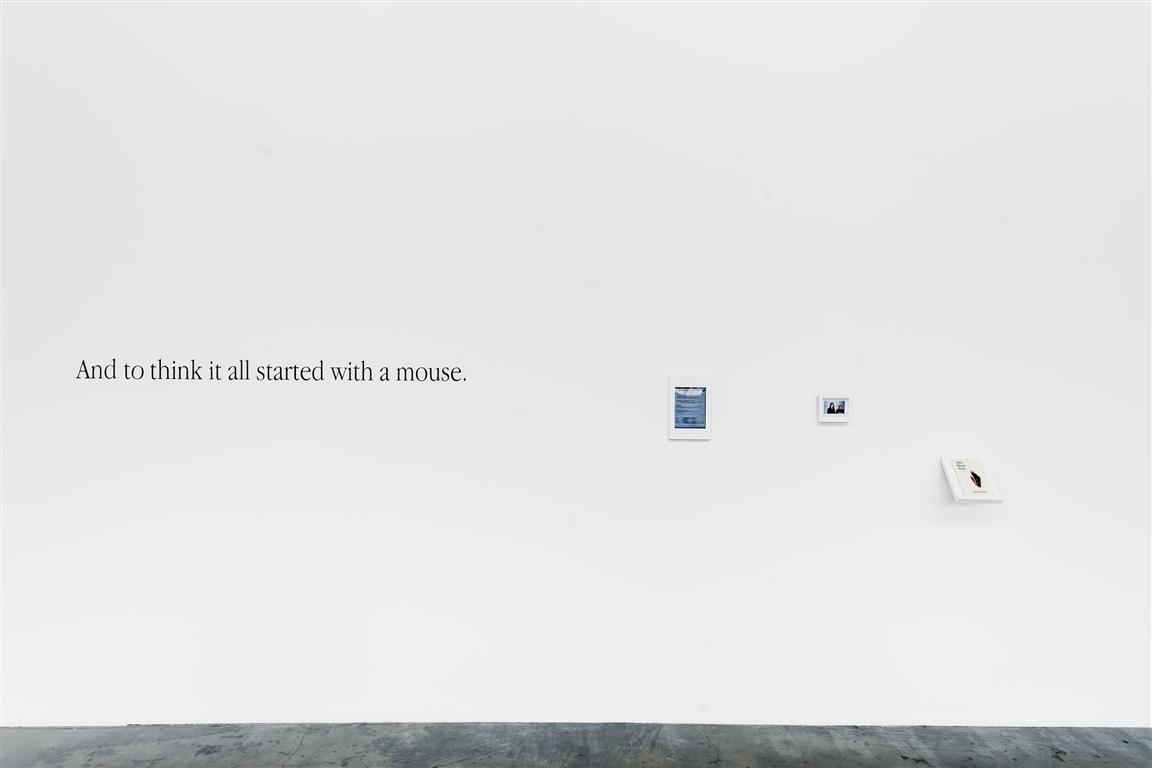

Speaking of Google, what's the status of that Haim Steinbach piece called and to think it all started with a mouse (1995/2004), the Google search results of which you modified as part of your project After, About, With (2013–15)?

I'm no longer actively manipulating the search results for Haim Steinbach as I was in 2013–14, but the content I produced as part of that project still represents a majority of the sites returned on page one for and to think it all started with a mouse. During that year I worked with art writers and curators (and I also created my own online material) to weight the reading of mouse toward a viable, but deliberate, consensus of interpretation: this work is about Walt Disney. The intervention contextualized a typographic coincidence that I discovered in relation to his font choice—Apple Garamond—that I teased out in an homage.

I honestly never thought it would be so easy to control the "meaning" of another artist's work in an online environment, but it only required exploiting a simple algorithmic principle: recent, widely dispersed, corroborative material is likely to be "accurate" and of interest. Distributed homogeneity is privileged by engines, privileged content is more likely to proliferate, and personalization/localization frameworks further promote information that's similar to information that's already been viewed. A dangerous echo chamber? Maybe. A powerful medium for artists? Certainly.

The days of the Disney ruse are numbered, though. Since the first of the year I've done a lot to contextualize the repeated readings. I published an artist book and have exhibited After, About, With twice (it's currently on view at Witte de With, Rotterdam). This article too will become part of that page one majority, especially since we've used Steinbach's name and the title of the piece several times already; but unlike the other references, these pieces are expository and big picture. The search results are shifting away from the fabricated "truthscape" and toward a new context that simply links my work with his.

Part of me was hoping that once Steinbach became aware of the project (through an exhibition we did together) he would fight back to reclaim his page one results. I imagined him hosting a series of his own carefully worded interviews where he discussed many different intentions for the work. So far that hasn't happened, but we'll see.

Julia Weist, After, About, With (2013-15)

Are you interested in longevity? So much of your work engages the internet as a constantly shifting site of meaning, and I wonder about your approach to this constant push-pull of changing readings.

I'm interested in creating an accurate portrait of longevity, as it pertains to both physical and digital meaning. Over the past nine years I've developed a collection of books discarded from American public libraries through routine processes to replace out-of-date information. This exercise proves that both online and offline meaning is so much a question of access. The word used in the Reach project was defined in context as two connected ropes, each with a noose on both ends. I take that as truth, partly because I know I will probably never find the word used anywhere else ever again. But you will take it as truth as well, because I've authored this meaning in several places and without challenge.

After, About, With culminated in an artist's book. You also wrote a (sexy!) novel and produce a lot of text around your works, which oftentimes has a very particular, almost romantic voice. How do you see the role of writing in your work? How does that relate to your background in library science?

I really enjoy writing and I find that it's often the only way to share the beginning, middle, and end of the very long-term and complicated projects I undertake. It's a part of my process that I look forward to, but I did find writing a romance novel very, very challenging. I like to write swift punches to the gut, a form of verse that is very much at home online, but more complex as a long-form style.

The library where I used to work was New York City's oldest lending library and it had incredible circulation records for some of New York's first avid readers. I remember noticing that John Jay's account had three consecutive checkouts of a three-volume novel called The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle and that he had read Arabian Nights and Don Quixote. It's hard to see that and not want to write in a way that moves people, where you can, within a visual practice. One of the things that I love most about sharing artwork online is how easy and natural it is to pair imagery with text, and I try to take advantage of that.

Julia Weist, With (detail, 2013)

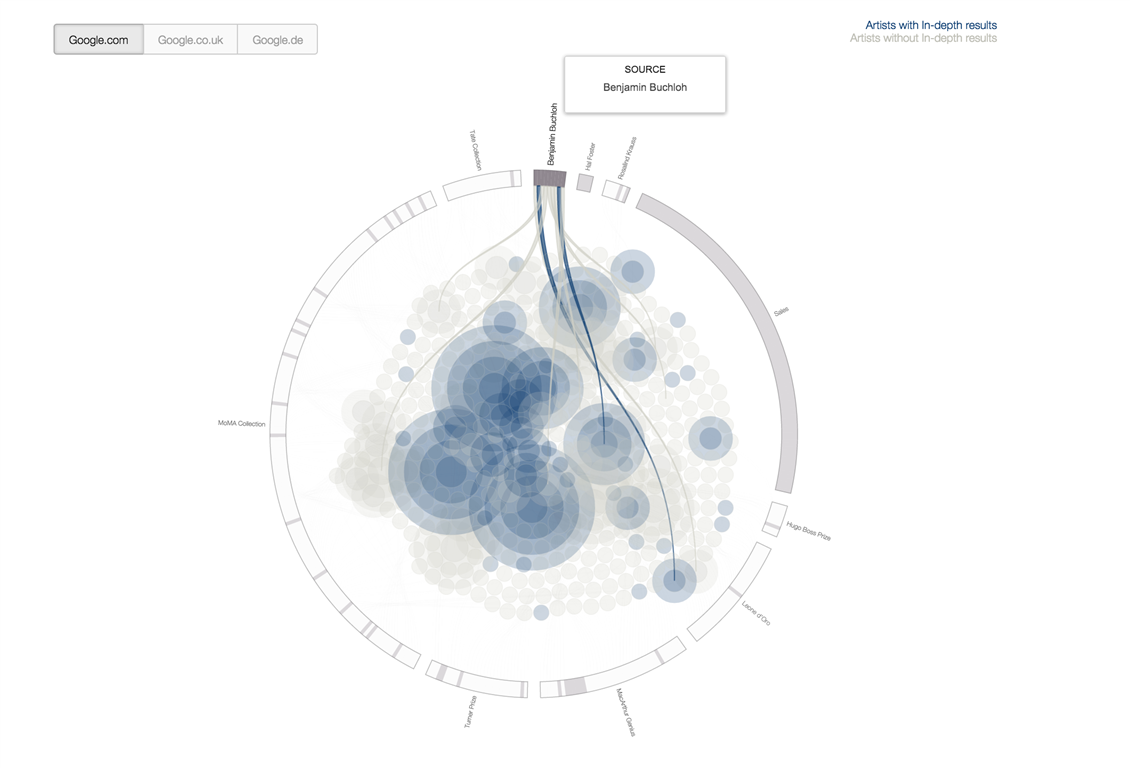

You use Google extensively in your work, both as a medium—After, About, With includes "search result set" as part of the caption, and the impetus for Reach was, in a way, to depart from Google sphere—and as primary resources for Industry vs. Machine (2015, which was commissioned for an issue of Red Hook Journal that I edited), which looks at the way the Google In-depth results may or may not construct a canon. What are some of the questions, complications, and possibilities that Google poses to you?

In another interview a few years ago I called the collection of the New York Public Library an "alternative exhibition space," and to a certain extent I now feel that way about Google, too. The beauty of the Reach project is that it's a piece anyone can explore, if they have the right password. And of course it's thrilling to try to work the system, to beat the engine at its own game for your own particular ends.

It's been said that there's a hierarchy from data to information to knowledge and wisdom. Increasingly we're interfacing with the bottom tiers of that hierarchy through tools that have only limited, if any, embedded ethics. Exploiting, visualizing, and departing from that sphere are the ways I know for how to test those limits.

Julia Weist, Industry vs. Machine: Canonization, Localization, and the Algorithm (information visualization commissioned by CCS Bard for the Red Hook Journal, 2014)

Questionnaire:

Age: 31

Location: Brooklyn, NY and Durham, NY

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

My dad was an early Mac user who was excited about the creative potential of technology. He shared that passion with me from a young age. When I was in fifth grade we made a video together to accompany a report I was writing on the Loch Ness Monster. It showed Nessie swimming lazily in a lake in southwestern Connecticut, through the magic of early CGI!

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I have a Bachelors of Fine Art from the Cooper Union and a Masters of Library & Information Science from Pratt Institution. I believe that the Cooper Union should return to a free education model or close. Nothing in between.

What do you do for a living, or what occupations have you held previously?

I'm an artist and an Information Scientist (at Whirl-i-gig, New York). Previously I was a librarian, a photo editor for biographical encyclopedias, and an artist's assistant for Janine Antoni and Spencer Finch. One of the best jobs I ever had was when I was 17 and I started my own business selling local baked goods at a farmer's market. I faced a few pie-related ethical dilemmas, which lead me to write to the old New York Times ethicist, Randy Cohen. We exchanged a few emails back and forth (btw, [email protected]) but I concealed the fact that I was a teenager.

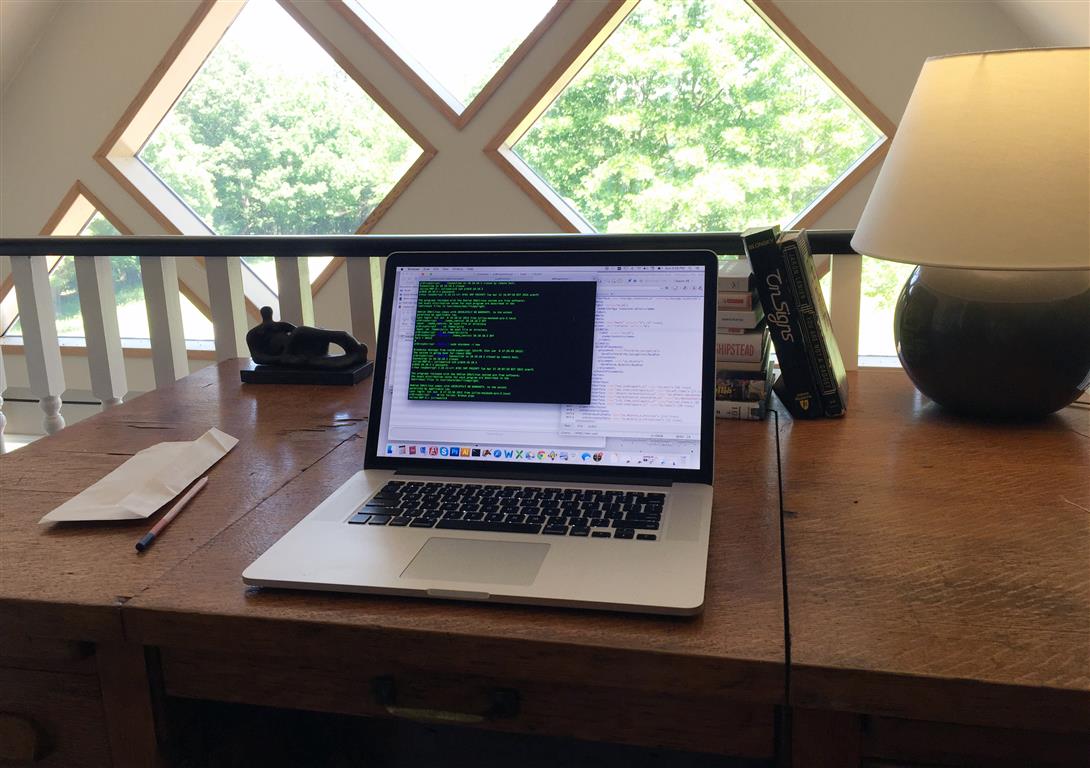

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!):

I'm currently renovating a new shared studio space with my husband, artist Andrés Laracuente, but I often work in front of a computer with my dog Fischer by my side.