What can be analyzed in my work, or criticized, are the questions that I ask…my composition arises out of asking questions.

— John Cage

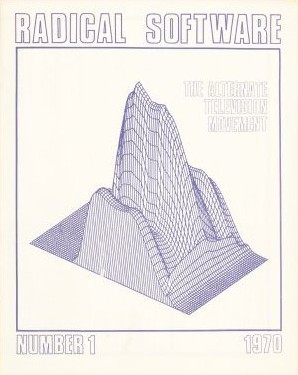

Radical Software Volume I, Number 1: the Alternate Television Movement (Spring 1970)

As rare as it is for something to be an instant success, this is what happened with Radical Software, a journal started in 1970 to bring a fresh direction to communication via personal and portable video equipment and other cybernetic explorations. Its intention was to foster an alternative to broadcast media and lessen the impact of its control. I was the co-founder.

When I began conceiving of the journal, no one really knew precisely what I was getting at because my ideas about it were at an inchoate stage of development, making for loose coherency. The idea was for individuals to be able to communicate interactively without the filters of broadcast media. Even at a more formalized stage the process superseded any formulaic views. Perhaps asking non-hierarchical questions could materialize the structures leading to a two-way network for communicative exchange. Our choices were no longer determined by traditions and customs.

I don't often look, but when I do, I notice so much misinformation, both printed and online, about the origins of Radical Software. I‘d like to clarify what my role was then and what my inspiration was in conceiving of it. It is important to set the background and tone of events. In order to accurately tell the tale I will weave in some personal life anecdotes from the time. It's all one story to me, as the vicissitudes of life often direct our fates.

Positano proved to be a pivotal place for me. There, I became part of a culturally and creatively informed transient art community. Artists like Vali Myers (1930-2003) lived in the valley between Positano and Amalfi in what had been Tiberius' herb garden with her architect mate Rudi Rappold and hundreds of animals. Shawn Phillips, the musician who co-wrote "Season of the Witch," also lived there. Amongst those passing through Positano was John "Hoppy" Hopkins (1937-2015), a scientist, photojournalist and political activist who helped found the underground paper the International Times, and his bride, the original Suzy Creamcheese. I learned about cybernetics and macrobiotics from him. The English-speaking travelers in this vertical Mediterranean village all bonded, socialized, dined, discussed and danced together. Later, at the theatre festival in Avignon, I discovered and became aligned with the artistic and politically avant-garde Living Theatre.In 1968-69 I was living in a loft in New York's Chinatown having recently returned from living in Positano, Italy. There, my six-year marriage had broken up when my husband, Ted Gershuny, left me for one of Warhol's Chelsea Girls, whom he'd cast in his first feature film. I had moved to Positano from New York, where I produced TV and radio commercials during the "Mad Men" period. I had also been making personal 8mm films for years.

I left Positano and returned to New York mostly because of finances. I rented and renovated the loft in Chinatown so I could paint and while there had a lot of time to think, imagine and dream. I read poetry and Scientific American as if it was poetry. The obscure terminology and imagery fueled my imagination and, along with the insightful conversations from Europe, created a desire to investigate the pre-existing structures of world of the late '60s. My intent was to sell everything and get back to Europe to make films.

While there, something happened that forced a swift change of plans. An acquaintance mailed me, from Morocco, a package of hashish formed into a gilded picture frame, addressing it not to me, but to a made-up name, I assume. I accepted the package. The Feds were in the stairwell and I was arrested, my passport taken away; I was released but confined to lower Manhattan. It would have been illegal for me to go above 14th Street. I never did see the picture frame. It took several years to clear this situation up. I was not guilty of anything. Meanwhile, Gershuny got a California divorce by falsely claiming not to know my whereabouts. No alimony. I was pregnant and not by him. Those were the underlying circumstances that led to Radical Software: curiosity and confinement.

I gave up the loft, sold its appurtenances and moved into a friend's tiny unoccupied apartment in the West Village with a bathtub in the kitchen and toilet in the hall. A sole window overlooking the alley let in little light, making it impossible to tell if it was day or night. Pregnant and penniless. I had little to do but dream, wonder, and drift and try to ward off loneliness and depression.

The Vietnam War cast a dark cloud over everything. All sorts of changes were in the air at the time, not the least being the rise of women's rights. My reading of Marshall McLuhan, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, Gregory Bateson, Samuel Beckett, Antonin Artaud, and Buckminster Fuller led me to question all sorts of societal norms and economic dysfunctions, as did my study of ecology, media ecology, spirituality, and Buddhism.

I worked briefly in the publicity department of Grove Press. Even normally dull filing was interesting there. I found the original manuscript of William Burroughs' "The Third Mind" — loose pages with drawings in a box. I couldn't resist taking it home to read. His multi-layered writing about communication and control aroused my imagination and seemed pertinent. Burroughs was staying in the apartment of producer Harrison Starr, directly across from where the Weather Underground explosion was to happen, in March 1970. I called and made an appointment to meet with him. I can't say he was warm and friendly, but he was receptive and we had a good chat. I remember discussing his idea of a "band" of people spread across a road, all with video cameras recording the same thing from a variety of perspectives.

All these encounters led me to ask myself: How is what they are talking about being applied? How are the means of communication controlled? What other ways are there to live? If you work for a company and invent something, do they really own your invention? Why are wireless cameras, currently used by the corporate media for sports events and war reportage, not available to the public? Why are corporations allowed to purchase publicly owned bands on the electromagnetic spectrum? Can light be sold? Why is technological advancement and research dedicated to the war machine rather than advancing civilization? A lot had been going on in 1968-69, especially politically and socially. There was a certain magic as well.

To answer these and other questions, I started making phone calls. People were receptive and willing to talk. I spoke with Douglas Davis (1933-2014), an art critic and media artist/activist. I spoke with scientists at Bell Labs. The more people I interviewed the clearer it became to me that I needed to form a questionnaire and eventually a newsletter.

I visited Global Village, one of the early video groups founded by John Reilly (1939-2013) and Rudi Stern (1936-2006), initially with Ira Schneider. Their collaboration with Ira was very brief. John offered me video classes but I wasn't interested. Then to Alan Douglas, a hipster music entrepreneur I knew through friends. I also visited Billy Klüver at Experiments in Art & Technology. I was getting nowhere because my ideas were still being formulated.

I soon received a phone call from Ira Schneider via Reilly. He and Beryl Korot came to visit. Beryl and I had a rapport and she was willing to proceed with sending out the questionnaire. Ira and Beryl lived together in a well-heeled doorman building on Fifth Avenue.

Beryl and I began meeting to discuss and reorganize the questionnaire and create a mailing list. The questionnaire ended up being more about using video than challenging any existing societal or economic forms.

When they returned, soon after my daughter was born, there was no place to move to and no funds. Everything felt very groundless. Davidson hung up some black plastic, ubiquitous in pre-Soho days, in a corner at the Videofreex loft on Prince Street and we lived there. No one knew what to make of me. I was not a member of Videofreex, but later became friends with several of them. What was happening in my personal life, compared with my active and creative mental state, made me feel split in half mentally and physically. I actively continued the work of producing Radical Software and stayed focused through all this personal turmoil.Meanwhile, my personal life was in flux. I had to move out of the little dark West Village apartment. My old friend Laura Cavestani, whom I met when we were fine art students at Boston University, introduced me to Davidson Gigliotti, one of the Videofreex. Davidson and I hit it off and he moved in with me. We then went to loft sit for my artist/poet friends, Vyt Bakaitis and Sharon Gilbert.

When the replies started coming in, Beryl and I retreated to media ecologist Paul Ryan's (1943-2013) cottage in New Paltz, newborn in tow, to edit, organize, and construct. A coherent story emerged from the input. Replies were arriving from groups and people all over the globe. We knew that the way news and information was disseminated affected everything. We knew there were a lot of like-minded people "out there"; we were hearing from them. Raindance was just one of the groups. We carefully read everything that people sent. As the replies and articles got edited to fit into the whole it became, for me, a kind of ventriloquism of mind. A coherent overview emerged; pointing it out was the editorial skill involved. We interpreted and edited, digested and synthesized, imagined and envisioned. The responses formed Radical Software.

One of the most generous contributions we made was the anti-copyright mark, signified by an x in the center of a circle, meaning DO copy. There were articles we wanted distributed, copied, and widely disseminated. Radical Software was never intended to be just about video as a social tool, or video art. As far as I was concerned it was about using technologies to extend the ways of communication outside the scope of large corporations and conglomerates that had, and still have, control. It was meant to be much broader in scope and more investigative.Only Beryl and I compiled and edited the material. It wasn't until we were about to have the magazine typeset that Beryl came to me and asked if Ira, in exchange for his help, mostly with the mailing list, could be listed as a co-founder. This had no real meaning for me at the time, so I said "sure." Ira had no actual input with me into the content or direction of what was to become Radical Software. Unfortunately, I did not know that my agreeing would later cause an unraveling of my own role with the magazine I had birthed.

It is important to stress the fact that Radical Software was a fait accompli BEFORE it was a journal published by Raindance, a "think tank" with no visible agenda. They became the publisher when it was necessary to find the funding to print what had already been created; the software itself, the content of the journal, was already present. The term "software" still confuses people, it can be regarded as the information itself and nothing to do with computer programs. But really it is the people themselves, the ones who create the information. Back then it was too soon to see that information was going to be the currency, as it is today.

By the time it was to be pasted up (in those days we did actual paste-ups with set type and glue plus press-on letters), I was in the ward at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. I had taken natural childbirth classes, considered too advanced for hospitals, from Elizabeth Bing who brought it to the U.S. Probably because of the stress, a clotting problem arose with breastfeeding that I ignored as long as I could while my fever rose. I was diagnosed with a tumor, but it was benign. My friends cared for my daughter while I spent time in the cancer ward. That stay aroused in me a great deal of sadness and compassion for this invisible world of suffering and changed me profoundly. When it was time to leave, I took the subway back to the Videofreex loft, alone and disoriented.

After being in the hospital, I immediately dove back into completing the work. There was a natural division of labor and collaboration between Beryl and me. She was much better with language. I had a clearer vision of format and presentation. The appearance was as important as the content. I had carte blanche; there was no one to interfere with any decisions. We were pretty much in agreement all the time. I envisioned the oversized format printed with a particular blue ink and a collaged style, much looser than straight columns, with non-linear juxtapositions. The use of blue ink and a random or collaged style of design was enough of a difference to indicate difference itself.

Raindance was composed of an elusive group. Some were visibly active, but others never made an appearance and I never met them. Raindance, though listed as the publisher on the masthead of Radical Software, was not the decision-making body. They were listed as publisher because what else could they be? It's led to a great deal of confusion. I had no direct dialogue with any of them, except for Shamberg and Paul Ryan. It was just something Beryl and I were doing and we were being supported in our attempt. Raindance was paying for it to be published. That might sound odd today. There were no actualities of collaboration or serving a publisher. It was not up to Raindance to make the decisions as to the content of Radical Software, at this stage. They were not the ones with the vision for this publication; many of them had their own visions that were included in the issues. Beryl and I analyzed what the next steps would be determined by the feedback received. For instance, by the time we got to Issue 3, I saw that so much was happening that a state-of-the art report was necessary.At that time, Raindance had acquired a spiffy office space on West 22th Street. I had stored my treasures there: a custom-made bed (Jimi Hendrix once slept in it) and classic Olympia typewriter. There was a break-in, and both items (and nothing else) were stolen. In the large main space were multi-level wooden platforms. Beryl and I were assigned the front room with two tables. Schneider and another Raindance member, Michael Shamberg, took the finished paste-ups to the printer and secured distribution.

The relationship with Raindance began to change after Issue One received a warm reception. The atmosphere in the office was not entirely welcoming. I was told someone named Louis Jaffe, who seemed to eye me with disdain, was the subscription manager. While it was clear a good deal of money had arrived, I only got a small amount for babysitting. I recall being told at the time that Shamberg, who was soon to become a Hollywood producer, had offered to pay for the printing, but apparently it came directly from Raindance. Recently, I read in The History of Video Art by Chris Meigh-Andrews that Louis Jaffe had given $70,000 to Raindance. He also indicated that Raindance hired Beryl and me to create Radical Software. I hope I've made it clear that it did not happen that way. I never really knew who paid, I simply trusted the process.

By the time Beryl and I completed Issue 2, there was an increasingly unfriendly atmosphere for me in that office. I had continuing ideas about the editorial and content direction. When we got to assembling Issue 3 my ideas were being censored. Interesting artist and poet friends of mine would stop by from time to time. The atmosphere was uptight and unfriendly, making me paranoid and uncomfortable. I had no contract and was basically an unpaid employee. The office behavior made me realize I was getting pushed out. I left before it was completed.

Radical Software Volume I, Number 2: the Electromagnetic Spectrum (Autumn 1970).

Without my realizing it at the time, Raindance was assuming proprietary ownership and had other ideas. My intuition and direction were being quashed. Ira didn't like my ideas; they were too esoteric. My brainchild, my labor of love, was being co-opted. Beryl and Ira took over Issue 3. They later decided to bring in a variety of people and the following issues were farmed out. I could have used the advice of a lawyer. I had already given attorney Ernst Rosenberger a retainer for the hashish picture frame case. L'esprit de l'escalier.

From the time we put together the first issue of Radical Software, we had to be careful not to take sides between the various emerging groups and individuals. It was all very sensitive and political in those days. Each group had its agenda and tendencies: some were more intellectual, theatrical, educational, square, just goofy and lowbrow, but no one had a real collective consciousness. When government grants from the New York State Council on the Arts started to come in, Raindance arranged to be the distributor of the funds. This caused a huge furor in the community and their role was soon rescinded. In retrospect, I can see how Raindance's policies undermined what I was trying to accomplish. Instead of a two-way network for communicative exchange, their apparent desire was to become a centralized decision-making body. There was reason to be suspicious. Large grants were given out to the various New York video and media groups in tens of thousands of dollars. A lot of video cameras were purchased. I never chose nor wanted to join Raindance, or any of the groups, and because of that I received no funds even though I had helped create a platform for the substantiation of a viable social movement.

I'd walked into a landscape with people I couldn't come to artistic or financial terms with and who represented an opposing view and ethic. I didn't want to live behind the black plastic curtain. My relationship with Davidson had fallen apart. One day I got into a cab with my baby daughter and a folding playpen and left for California with little prior notice. My sudden departure became a mythological tale greatly appreciated and told many times over by Nam June Paik. I really thought I could link up with some like-minded people or even be able to add to Radical Software from there. I was never able to continue the power and source of that work. The West coast was an entirely different culture. I was lost for some time.

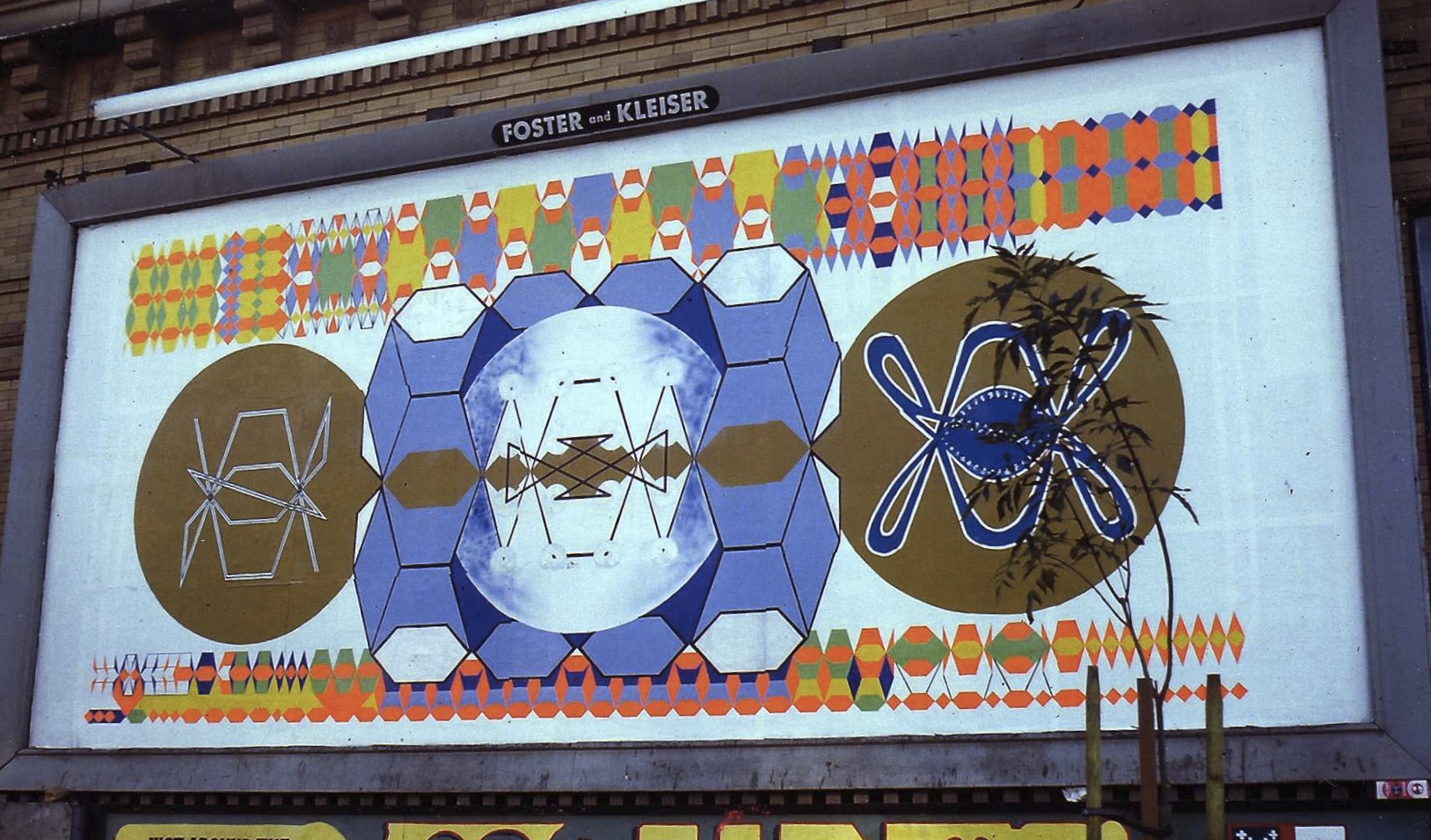

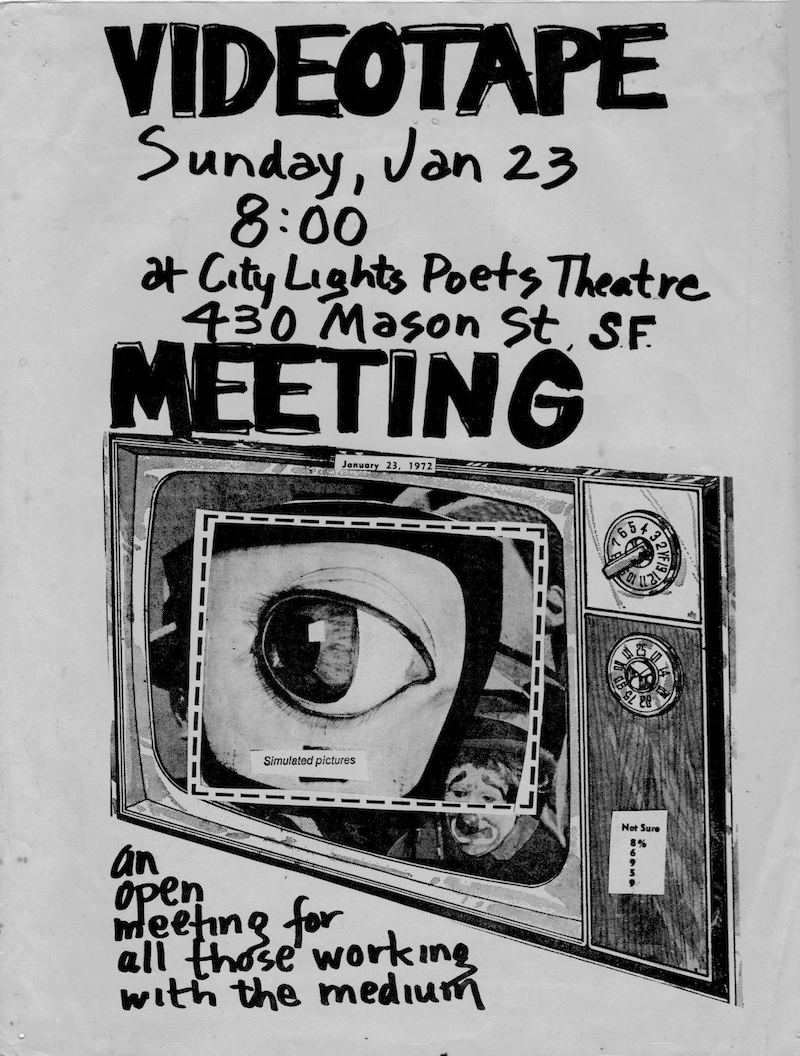

In San Francisco, I became friends with Jerry Pethick and Lloyd Cross, founders of the School of Holography, and created holograms both there and at Stanford University. I put up hand-drawn, collaged, posters in 1972 that drew quite a crowd and boosted the video movement there. A Frenchman named Francois showed up looking for the "Queen of Video." In 1973, I created a hand-painted non-advertising billboard based on the magic square of 16, drawn from my studies with filmmaker, Jordan Belson.

Hand-painted billboard, 1973.

Years later, visiting New York, I dropped by to see C.T. Lui of the eponymous electronics store. He told me I'd gotten a $1000 NYSCA CAPS grant for individuals while working on Radical Software. I never received it but someone did. I phoned the Council and inquired. It was the kind of grant that could have been used for anything, even buying refrigerators, the director said. Or, diapers.

Around 1983, after I had moved back to New York, I got wind that a panel discussion about Radical Software was to take place at La Mama. I went. Davidson was the MC. Ira Schneider was on the panel of experts. I can't remember the others. All of them discussed Radical Software referring to it as a sacred object. A man sitting next to Ira, who I had never seen in my life, recalled being there when it first "came off the presses." They then passed the first issue around to the audience. In amazement at the chutzpah, I said nothing. I was in letting-go mode after having spent several years practicing Buddhism and meditation. I walked off arm-in-arm with gallerist Howard Wise, who had exhibited early video art.

In the early 90s, Davidson called to tell me he and Ira were planning to put the issues of Radical Software online. If I gave permission, he'd send me $500. Davidson gave his historic overview without any consultation with me, and I never discussed any origination details with him. Just about all the biographical information about me is incorrect, and even the photograph posted is not the one I sent. The positive aspect of an online presence for Radical Software was offset by the further substantiation of Raindance as an entity.

In the 2002 Artforum article "Tale of the Tape" by David Joselit, he states that the lasting legacy of Raindance was Radical Software. In a private conversation with me, he noted that the first two issues were more interesting and noticeably different. They made a case for combining art and activism, interactivity, and feedback. The juxtaposition of the technological and new agey with vectors, charts, and theory made it unique. I had hoped to see Radical Software evolve into large format posters to be read off the wall and packaged with a live video magazine. There was no reason the format had to remain static. I also envisioned more futuristic viewing spaces rather than the pedestrian darkened chambers that still exist in museums today.

In April 2013, the School of Visual Arts (SVA), in New York, hosted a panel called "We're All Videofreex." I was surprised when introduced to many attendees that I was greeted with exclamations like, "I can't believe I'm meeting you," or "no one knew where you were." Most were a part of the scholarly movement who want to make sure that Radical Software keeps its place in the film/video/digital history. They still referred to me as Phyllis Gershuny. I felt like the Rodriguez of the video movement.

Beryl and I did converse a few years ago and would meet infrequently to visit art galleries in New York. When I proposed that we videotape a conversation, with an interviewer, over a dinner, to reflect upon what Radical Software might be today, Beryl was skeptical about the idea but willing to discuss it. We met once with David Ross, a possible interviewer, but the chemistry was lacking. It would be interesting to have an exchange with others about creating a modern version of Radical Software.

Now, at the pre-teen era of the Information Age, the barrage of data is in a state of free-for-all. Information rarely gets sorted out to enable distinct cultural meaning. It was thought at one time that through feedback loops and interactivity a platform for self-correction would emerge in the culture, rather than relentless self pre-occupation. Misinformation and counter-information have piled up like so much debris. Data arrives quickly and in quips, speeded up and sensationalized. Users can hardly lift their heads or move their thumbs fast enough to keep up with the flow of attention demands.Video did enable people to see themselves as if for the first time. You'd look and see and be able to self-correct motions, attitudes and more. It extended the mirror for greater psychological and physical adjustment. We never foresaw the internet or iPhone or YouTube. It wasn't until 1993, with the first graphical web browser, that media technology and digital culture met to become a popular medium.

Control mechanisms are over-layered, felt by some in a psychological atmosphere, but hardly deduced by others. Thus messages are systematically regurgitated resulting in feelings of frustration and loss. There are more wars and they are endless. There is talk of our own pending extinction. Mass media and information technology have deepened the mind-body split by causing emotionally fixated conjectures regularly. Or as Hakim Bey writes: …fixating our flow of attention on alienated information rather than direct face-to-face and embodied experiences of material human life, the core of any genuine human freedom. Websites abound with self-proclaimed shamans. If this is pre-teen, what will the teens bring, and early adulthood? Each decade of human life seems pre-conditioned genetically to deal with specific concerns so perhaps the same relationship exists between information and the unseen.

As for the electromagnetic spectrum, there are economists, like Peter Barnes, who propose that fees for that and other resources be shared with everyone who holds a Social Security card. I'd say everyone who has a birth certificate.

If it's all in your mind, the corporate media giants own your mind. At the still core of consciousness lies the unspoken feeling that sanity can be regained. Too esoteric? Be reassured. Notice your senses. Come to them. Assume control. Sweep away the crumbs. Be kind. Ask your questions and wait for the responses. Listen. Meditate. Perhaps a fair and fluid new operating ecosystem can be summoned from thin air.

Hand-made flyer for Videotape Meeting at City Lights Poet's Theatre, January 1972.