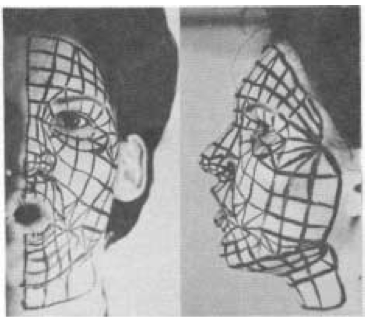

Still frame from Fred Parke, Faces, University of Utah, 1974.

On June 19 of this past year Miley Cyrus released a video for "We Can't Stop," the lead single for her fourth studio alum Bangers (2013). Directed by Diane Martel, the video was the first step in a massive rebranding effort by the young singer, who has transformed herself from a Disney teen starlet into a bad-girl human Tumblr. The video largely consists of the young star partying with friends, intercut with a number of visual non-sequiturs that resemble scrolling through the popular microblogging platform. The video, album, and subsequent MTV video music awards performance have sparked a number of interesting debates online and in popular press concerning sexuality, race, and appropriation. Watching the video for the first time, I was shocked, though not at the twerking or the tongue or the dancing bears. "Did you see that?" I yelled as I paused the video. "I think that was the CGI face from Fred Parke's 1974 University of Utah dissertation research." And it was.

Frederic Ira Parke is a computer scientist and professor in the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M University, but in the early 1970s he was a graduate student at the University of Utah completing his dissertation research on the modeling and animation of human faces. At the time the University of Utah was the most prominent research center for computer graphics in the country. Funded largely by the US Department of Defense, the program's primary goal was the construction of early interactive graphics for flight simulation. Almost all fundamental principals of modern computer graphics were developed at Utah in the roughly fifteen-year period from 1965-1979, including raster graphics, framebuffers, texture mapping, and object shading. Among Parke's colleagues during this period were the founders of Pixar, Adobe, Netscape, and Atari.

Parke was one of the first researchers to digitize the human face, and the earliest researcher to experiment with facial expression through computer animation. This work began with Parke's master's thesis (Utah '72), in which he demonstrated the feasibility of animating a range of realistic expressions on a computer generated facial model. That same year, Parke's colleague Ed Catmull used a similar system to digitize and animate his own hand in what is one of the earliest examples of fully shaded 3D computer animation. The digital hand was made using a plaster model and digitized with a coordinate measuring machine. The resulting animation sequences were edited into a film, and in 1976 they would become the first digital computer animation to be used in a feature length film, appearing on screen in Richard Heffron's Futureworld (1976).

40 Year Old 3D Computer Graphics (Pixar, 1972).

For Parke's doctoral dissertation (Utah '74), he decided to take his research one step further, making the faces change and transform using linear interpolation. This "morph" effect is now common in computer animation, but in 1974 it was unprecedented. Parke calls these shifts "transformations," and while his focus is on faces, the technique could be applied to any number of objects. The faces are based on data taken from human subjects, who would have half of their face drawn on and divided into sections that could be used to produce the polygonal structure of the simulated face. The model could then be mirrored to create a full symmetrical face. Parke's dissertation is much more detailed than his earlier work, and includes a complex parametric model whereby various parts of the face are divided into relational nodes and effected by a number of parameters such as shape, arch, position, and color.

A typical pair of facial data photographs, from Parke's "Computer Generated Animation of Faces" (1972).

The project also includes one of the earliest examples of speech synchronization in which a computer-animated head recites Emily Dickinson's "How Happy is the Little Stone." It is from the film Parke made to document his research, simply titled Faces (1974), that the Miley Cyrus clip is taken, looped back and forth to make it appear that this milestone of early computer graphics research wants you to know that "It's our party we can do what we want."

While these images now look like any first year computer animation demo reel, it's important to remember how completely different the tools and methods for producing computer animation was in the 1970s.

Image output was done using a slow scan CRT that showed the image one scan line at a time. Each black and white image took about 30 seconds to scan out. You couldn't actually "see" the complete images directly. They were recorded on photographic film, either on 4x5 polaroid for test images or on 35mm movie film for animation.[1]

While rendering is still a time consuming and resource intensive process, Parke had to wait weeks before viewing his animations, which had to be transferred across multiple analog and digital formats. Parke notes, "the animation production cycle was as follows:

- Write and debug your animation programs

- Create the data files to drive the animation

- Test both as much as possible (without actually seeing any animation output)

- Run the programs to produce the animation images on 35mm cine film

- Send the film to Los Angeles because no place in Salt Lake could process it

- Wait about one week…

- Get the processed 35mm negative cine film back

- Have a 16mm "timed" print of the film made because we didn't have access to a 35mm projector

- Wait several more days…

- View the 16mm film and see what worked and what didn't

- Loop back to step 1."[2]

Video had no part in the process—all images were produced using analog film cameras that would be physically attached to the cathode ray tube screen or housed in a darkened unit built specifically for this purpose.

It's hard to know how Fred Parke's work ended up in one of Miley Cyrus' newest music videos. The director did not respond to requests sent via her agent, and Fred Parke seems unsure as well.[3] One can speculate that the images were intended to invoke a kind of tech-y nostalgia, or signal a generic, retro digital aesthetic. To be sure, the use of these images was not meant to foreground the historical significance of Parke's graduate research at the University of Utah. Yet if we look closer, these old images cease to be mere references in support of Cyrus' highly orchestrated public brand; they become strange and singular objects held together by painted faces, Polaroid cameras, and Emily Dickinson poems. More than that, Parke's work reflects the desire long held by computer graphics researchers to simulate objects as complex and singular as the human face, to animate the inanimate, and to capture the world in all its complexity.