The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Nick DeMarco

You hop felicitously from medium to medium: sculptures, gifs, videos, fonts,T-shirts, tweets, products, furniture, and guerilla culture-jamming. I want to talk about your sensibility, which is identifiable throughout your different projects. I remember three descriptions that you yourself have used: "Transcendental banality," "Funky lil-ness" and "Dilbert on acid." They each point to something, so I thought we could riff on them a little, beginning with "Transcendental banality."

I've phased out "Transcendental banality" because it sounded kinda wanky, but it was really one of the first ways in which I tried to describe what I was doing. I came up with it early on in school, where I was interested in both art and design. Art was supposed to be this more transcendental thing—and a failure if it became banal. Design that became banal, however, was considered a success—so successful that it became ubiquitous. Now, the phrase seems a little trite because everyone is interested in "The mundane" in a very NPR kind of way. But for me, it wasn't so much about elevating the mundane in itself, but inserting myself into it and melting into it in my own way. I'm very much an opportunist in that the things around you are usually such wasted opportunities for the transcendent. That's kind of what I meant.

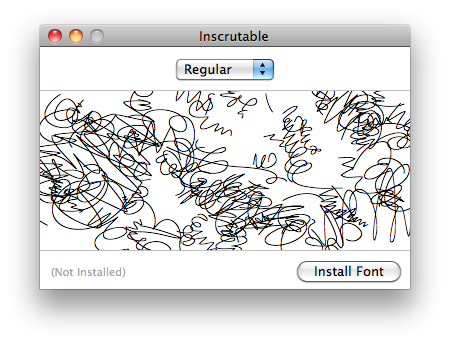

It seems you'd be unfazed without museums or galleries—not that you're against them in any way, just that you'd be as comfortable or excited if a restaurant approached you to make their toothpick dispensers or if NPR asked for a ten minute Nick show. Or, to use a real example, like the "abstract" font you made, Inscrutable Regular, which produces doodles all over the screen as you type. It seemed like just one more opportunity for you, though I can't imagine it becoming a new standard in Switzerland.

Nick DeMarco, promotional image for Inscrutable Regular font (2013).

What's funny is that it kinda did take off—at least among graphic designers. Type is its own really intense little world. And it's true that this font is a project encapsulating a lot of what I'm into. It's a working typeface. It works everywhere—Microsoft Word or wherever—and from the computer's perspective, when you type "A," that's still an "A." That's what an "A" looks like now. But for us, what comes out is this scribbledy-gobbledegook. For the computer, a letter is a letter.

Idleness is a huge motif for you as a productive principle —not in the sense of being lazy, but in that I imagine your creative heroes to be more in line with the shirkers of the world or the dads using the office copier to sublime ends, carving out a weird space for themselves and then taking it all the way. I was thinking about your furniture designs like Daydreamer or Zen desks—or the Žižek piece where you're shining a laser pointer on him giving a lecture.

At first, I didn't like the term "idle" because I'm somebody who tries to generate as much dope content as possible. But maybe idleness is the right word—or at least where I feel athome. It definitely ties into my observationalism. A lot of my art comes from observation, from looking, which is a very idle thing. With "Dilbert on Acid," I love the idea of worlds within worlds; that you can make your own reality without having to leave everybody else's reality behind. This is also a lot like acid, only I'm making it more concrete.

The Žižek one really sums it up well, as a gesture. To me, laser pointers are such incredible tools, and one of the laziest things you can do. I bought this super powerful laser. I was shining it on the Brooklyn Bridge, into the windows of parties, everywhere. It makes time and space meaningless. It gives you this incredible power to do nothing—all this pretty sophisticated technology just to point at something…Which is ultimately what all artists do: point at things.

So who are your key artistic influences, or how did you come to roll with the crews that you roll with?

Every time I try to answer this question straight, I feel like I'm lying on some level; because I'm not motivated by artists in a direct way. I definitely get pumped on others like James Turrell, Cory Arcangel, Nasty Nets, Joel Holmberg, Ryan Trecartin. I'm not saying I work in isolation, but when I'm making something, it doesn't necessarily feel in response to their work—as influence—so it makes it hard for me to say. I'm sure I have been influenced, though. Parker Ito and I met in freshman year English class and became friends right away, and were both really into the internet. I knew about some net art people—Cory Arcangel or Rafaël Rozendaal. Then Parker turned me on to others, like Guthrie [Lonergan]. We were both on del.icio.us, and I was making a lot of gifs; and then JstChillin happened, which was organized by Parker Ito and Caitlin Denny. We had this crew, centered in San Francisco, which also included people like Zach Shipko and Body by Body. And still now, as far as influences or favorite artists—most of them are my friends. I will say that seeing Guthrie's work, acknowledged on the cover of Artforum, was really inspiring.

Maybe now is a good time to switch to your investigation of "Funky lil-ness," as in "I made a funky lil' end table" or "I'm working on some funky lil' markers." You've also used it to describe objects not of your own creation in a way that signals you're at peace with other people's creative endeavors: a community parade, for example, or a shopkeeper who's made a "funky lil' sign."

"Funky lil"... Hmm, well, now it's just become this thing that I can't stop saying. I was using it a lot to describe some... (pauses to reflect)... intangible quality, in which the thing stands out from everything around it, but in a way that means you may not notice at first. It's not in-your-face funky. It's not over-the-top funky. It's more like "Hey, check out this funky lil' guy. We're all just hanging out, and this guy's here too—and maybe he's a little different."

I'm a self-expression junkie. I like seeing people that are fully pumped on the things they're pumped on, or objects that are fully pumped on being themselves. That is, if they're all in. Even if it's some regular person walking down the street with a weird hat on, or even a street sign with a weird lean. "Funky lil" ties into this—it's letting a thing be or become its weird self.

Nick DeMarco, Tims Couch (2013).

Since this is for Rhizome, let's conclude with a question about the digital or the internet, where you still make or place the bulk of your projects. When we first met, you mentioned that, at least in the early days, the internet afforded you an opportunity for "art without logistics"—in that its newer modes of production and distribution and the social circles which formed around them allowed you to kind of leap over the older ones in a really liberating way. What's your opinion on the gallerization of work that was originally made under or for the conditions of the internet or its "ensemble of networked technologies?"

The gallerization part can be a bummer just because what's so great about the internet is that we're doing it ourselves, under our own rules, our own value systems, but then suddenly have to return to somebody else's. The fact that it's physical—that doesn't matter to me. It's beside the point. I'm not a digital snob or digital purist at all. Of course, there are still power structures on the internet, whether it's Facebook or del.icio.us. or whatever. These are all power structures, but power structures that you can shake or leverage in different ways. I also don't look at the internet as this really idealized, utopian place. It's just an alternate reality where the limits and the restrictions are different. And it's always fun to work with new sets of restrictions, and move between them.

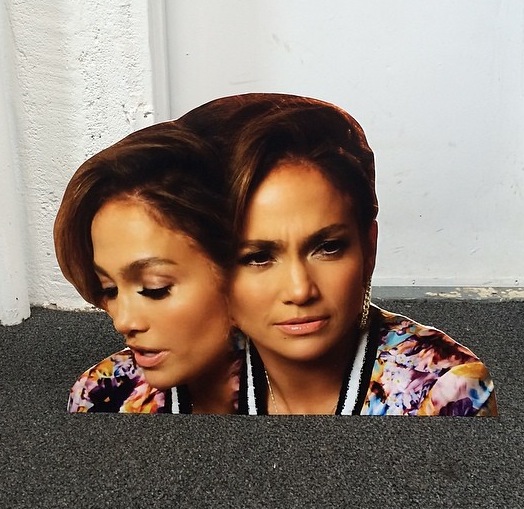

Nick DeMarco, Jennifer Lopez as Gabriella Gonzalez (2014). Installation view from the exhibition "Here on Earth," Interstate Projects, Brooklyn.

Age? 28.

Location? New York City.

How long have you been working with technology?

Forever. My mom worked from home and had a computer in the house. We had Pagemaker and an early version of Photoshop. I've had a lasso tool in my hand since middle school or earlier. It's always been present. However most of what I do is Decoupage, only with copy-and-paste. I trust that the internet will provide and go in search of "X" without necessarily knowing what "X" is or how it works, exactly. Then I just go in and maybe change a 6 to a 7 and then—suddenly—I remember that that's what I wanted all along.

Where did you go to school and what did you study?

I studied anthropology; then went to CCA to study art and design.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I try to work as little as possible.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)

I have a studio in the Bronx, which is pretty raw, a little funky, and very bohemian. Right now my desktop wallpaper is a picture of a dog wearing reading glasses.

Nick DeMarco's solo exhibiiton "Here on Earth" opens Saturday at Interstate Projects in Brooklyn, NY.