Photo of Salon de Thé Facebook, Tunis, shared on Twitter by @WadhahJebri on February 16, 2011 and recirculated with the #16juin2014 hashtag.

It sounds, at first, like something out of H.G. Wells. On February 16, 2011, a person opening a Tunisian newspaper or website might have come across an article dated more than three years in the future.

Following the Sidi Bouzid Revolt in January 2011 which ousted the president, the country experienced a national strike which halted economic activity, and the transition government swiftly lost the confidence and goodwill of the people. A Tunisian ad agency, Memac Ogilvy Label Tunisia, embarked on a campaign to convince Tunisia's media outlets to join together for one day to report news from 2014.

We needed to find a way to encourage the people to get back to work and start rebuilding the country we had all fought for… So we decided to show everyone how bright our future could be if we all started building it now… During a whole day, the media acted as if it were June 16th 2014 and presented Tunisia as a prosperous, modern and democratic country… The media content spread to social media via 16juin2014.com and people began to imagine wonderful futures and called everyone for action. #16juin2014 hashtag was n°1 top trend topic on Twitter all day long. At 6pm, the debate was everywhere on TV, radios, blogs… Getting back to work quickly became an act of resistance.

When I visited the 16 Juin 2014 website (sadly no longer active, but available via the WayBack Machine), what struck me about the news being reported was how uneventful it was. Using Google to auto-translate the title of the clip revealed that the major news item was about a "Shopping Festival" in the town of Kasserine, featuring interviews with celebrity fashion designers Giorgio Armani and Marc Ecko. There was discussion of a giant Daft Punk concert in Tunisia, and the leading newspaper La Presse boasted of the Museum of the Revolution joining the ranks of the 50 most-visited tourist destinations worldwide. As a vision of the future, it seemed rather modest. But then, given the turmoil that spread across the country just several months before these articles were written, uneventful may be ambitious enough.

Top: Front page of La Presse on February 16, 2011. Bottom: inside page of La Presse with fictional advertisement announcing the opening of the 12th McDonalds in Douz, Tunisia.

In the last few years, new strategies have emerged for facilitating discussion and thought about the future. Dubbed "Experiential Futures" by futurist Stuart Candy, these approaches sidestep intellectual discussion in favor of provoking more emotional responses by embodying elements of hypothetical futures into present-day artworks, films, and performances, such as newspapers from the future.

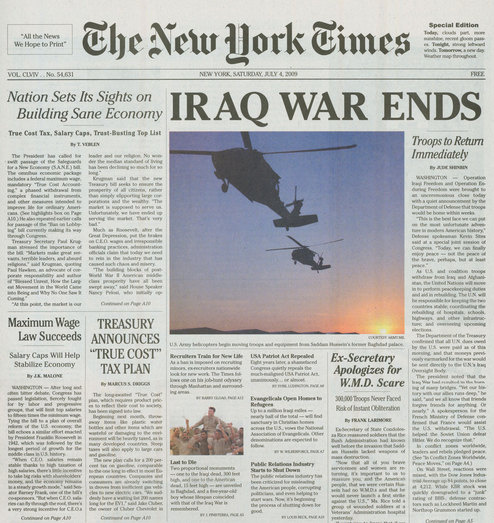

#16juin2014 isn't the only example of an Experiential Future in the form of a newspaper. In 2008, a collaborative group of political activists and mischief-makers carried out a major stunt, producing and distributing 1.2 million copies of a "special edition" of the New York Times from 2009. This newspaper of the future perfectly replicated the design and layout of the original, but with a telling edit of the Times' motto, from "All the news that's fit to print" to "All the news we hope to print."

The New York Times Special Edition Video News Release (Nov. 12, 2008).

The content of the fake NYT was as aspirational as the Yes Men's motto suggested: front page headlines included "Iraq War Ends," "Ex-Secretary Apologizes for WMD Scare," "Maximum Wage Law Succeeds," and "Nation Sets Its Sights On Building Sane Economy."

In 2013, two years after a massive earthquake devastated the city, Christchurch newspaper The Press produced an edition of the paper reporting from 2031. Articles covered New Zealand politics, city planning, the impacts of climate change, and local Christchurch sports and arts, from the perspective of 20 years after the earthquake. The aim of the exercise was to prompt Christchurch citizens to look beyond the recent disaster and to "Rally, protest, cheer, plant ... do something that changes the future."

The 2011 Lecturas de Cruce ("Crossing Lectures"), organized by SF author Pepe Colo and his media studies students from the Autonomous University of Baja California, tapped into the potential of the border as a place from which to envision the future. Alongside a dispensary of free science fiction books, dance performances by pre-programmed cyborgs, a procession dedicated to a cyborg saint called Santa Ste.la, a newspaper from the future was handed out to cars queued in the hours-long line to cross the US-Mexico border.

The Procession of Stanta Ste.la at Lecturas de Cruce

These are among a scattering of recent newspapers and other media outlets around the world that have published editions reporting from hypothetical futures. This is hardly a trend—the few examples I'm aware of are so disparate that it is more likely to be convergent evolution, with each paper coming up with the idea independently.

What is the point of this practice? The short answer is that there are too few opportunities for people to come together in public discussion about the future. Future forecasting is generally left to the "experts." Science fiction offers a more populist approach, but it too often offers a nearly unrecognizable image of the world. The newspaper format—digital or print—is effective because of its familiarity to so many people, and because of its aura of authority. Seeing a well-known media outlet describing events of the future has the potential to prompt concrete thinking and widespread discussion about what lies ahead.

That's the theory, anyway, although it is difficult to assess its effectiveness. Three years after #16juin2014, Tunisian artist Noureddine El Hani described the initiative in positive terms:

The waking dream was like a flash in the pan (un feu de paille, literally a fire of straw); it didn't last more than a moment, but it was useful in the sense that it permitted one to disengage from the real, it created a small sphere of hopes and desires for, and projections onto, the future. It is indispensable in times of crisis—whether economic, national, or emotional! Being a continual transgression, art doesn't make sense except to the extent that it comes from the imagination to build a dream world. The video… was received with pleasure, I think, at the time even though the economic situation of the country leaves something to be desired since! But the fact of imagining, thanks to new technologies, better horizons give a glimmer of hope and offer a certain enchantment for the viewer even if he or she knows it is utopian.

El Hani's remarks echo Steve Duncombe's argument that the "impossible dreams" of Experiential Futures "open up a space for democratic participation in the process of imagining the future, which also offers the possibility of escaping the tyranny of the present... for people to imagine, 'why not?', and 'what if?'"

However, some Tunisian commentators, including independent critical blog Nawaat.org, put forward the argument that #16juin2014 was less a democratic vision of the future than an elitist one (see: Armani & Ecko). Journalist Frida Dahmani questioned the suddenness of the campaign, arguing that it was too soon for Tunisians to even be sure of their current situation, let alone imagine its future, and questioned the value of a future visioning exercise led by an ad agency and carried out by a small elite against the backdrop of a general strike. Rather than taking time to reconnect with what the country wants and needs, the #16juin2014 operation seems "like a big joke mounted by a bunch of friends at a party in the [affluent] northern suburbs."

The wildly aspirational, almost euphoric vision of 2009 in The New York Times Special Edition was also not uncontested. Its makers, a group that included Steve Lambert, Andy Bichlbaum of The Yes Men, 30 writers, 50 advisors, 1000 volunteer distributors, CODEPINK, May First/People Link, Evil Twin, Improv Everywhere and Not An Alternative, were less concerned with making realistic predictions of the future than with prompting a call to action, with the immediate intended result of a celebratory end-of-the-war street party. Their dazzling, egalitarian, humanist alternative to the dismal futures then being debated by politicians on the left and right was at first glance absurd, but so richly detailed that readers couldn't help asking themselves, "Why not?"

The New York Times Special Edition, 2008

One of the original collaborators, artist and editor Anne Elizabeth Moore, left the project before it was published; she later discussed the fact that the political content of the paper changed after her departure:

A ton of stuff was cut–much of it the most engaged critical stuff... Perhaps coincidentally, most content by female contributors was cut… This was where writers–original contributors to this vision–started to get screwed. When their work was changed or dropped without consultation, I mean fake paper or not, that’s really exploitive of people’s labor, and just generally kind of unethical. Made more disturbing by the utopic vision and structure of this paper. Because whose ideal vision of the future includes having their contributions ignored or changed without consultation? Which is sort of a great lesson in how supposed utopias operate, I guess.

Like #16juin2014, like all such projects, The New York Times Special Edition represented a particular set of voices and their political beliefs and assumptions. Nevertheless, it also represented a moment of possibility, bringing otherwise unexpressed hopes and dreams back into the broader political conversation.

It's hard to prove that newspapers of the future as a whole contribute to social change in any meaningful way. They don't solve the underlying problems involved in facilitating a truly collective dialogue about what lies ahead, and there is always some line drawn between those who are included in the discussion, and those who are not.

Yet as a popular medium with a particularly strong claim on reality, the newspaper (in its paper and digital versions) does have the potential to reach a wide audience and invite readers into a process of visualization. Visualizing a preferred future may only be a first step—the next is visualizing the process needed to make it happen. Still, considering that most of the time we do neither, any prompt that reminds us that the future is not fixed, but up for grabs, can only be a positive. In this sense, most newspapers from hypothetical futures are, at least, gestures in the right direction.