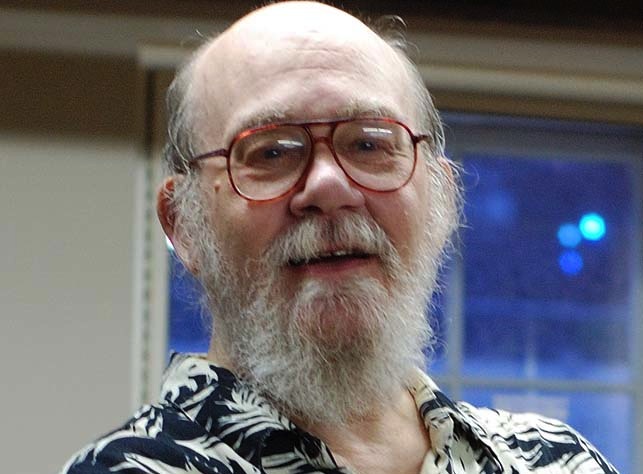

Ariel Hameon, Science fiction author Thomas M. Disch at South Street Seaport (2008). Via Flickr. June 3, 2008. Some rights reserved.

"This Journal is a memorial. New entries cannot be posted to it." So reads the banner above Thomas M. Disch's Endzone, a LiveJournal kept from April 26, 2006 until July 2, 2008, two days before Disch's death. Disch left behind a prolific output of poetry, criticism, libretti, plays, film treatments, and text for computer games, but it is a series of highly-stylized and vicious fictions presenting a hopeless America as stand-in for mankind for which he is primarily remembered. His novels Camp Concentration (1968) and 334 (1972) are twin high points of New Wave science fiction. The former prefigures David Markson's Wittgenstein's Mistress in its referential narrative; the latter is a scabrous satire of the social novel circa 2025. Endzone does not live up to the stylistic mastery of its precursors; as its author's first encounter with what may be considered a bastard form, it is at times near amateur in composition. It is also xenophobic, vindictive, full of doggerel and despair, and altogether difficult to endure. Despite its shortcomings, though, Endzone should be considered Disch's final work, if only for its brinksmanship with his career-long obsession with death.

As fellow author and critic John Clute has observed, Disch treated death "as a game, deadly of course, but beauteous" throughout his entire career. His first novel The Genocides (1965) ends with the extinction of the human race. 334's (1972) final monologue is in the form of a verbal application for euthanasia. Death is explicitly referenced in the titles of Endzone and his 1973 story collection Getting Into Death. In The M.D.: A Horror Story (1991), a god strikes a bargain with a preteen unable to grasp its grave consequences. Here is Disch's worldview in miniature: we are doomed by forces we have no conception of, forces which invariably bring out the worst in us. The M.D. is part of Disch's Supernatural Minnesota quartet which takes place in a mid-American landscape where supernatural forces manipulate humans via desire, hate, and despair, and God is understood only through his absence. The best thing that can happen when you're in a Tom Disch book is to die and die fast.

Disch died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound on July 4, 2008, and, if one so desires, Endzone can be read as a suicide letter. But then, so could his entire body of work; the reduction of any writer's output, whether it be that of Sarah Kane, David Foster Wallace or Hunter S. Thompson, to an explanation of his or her suicide divests it of intention and frisson. It reduces the novelist to a patient of post-mortem psychotherapy. Clute, reversing this impulse, wrote that Disch took his own life "to demonstrate that he really had meant what he had been saying over [his] career."

Disch had a wealth of travails: sciatica, diabetes, the recent death of Charles Naylor, his partner of some thirty years, the flooding and subsequent uninhabitable nature of their house in upstate New York, difficulty in walking, near-obesity, the constant threat of eviction, arthritis, and the not entirely unfounded conception that his place in the publishing world had, and would continue, to diminish. Endzone seldom deals with these sufferings explicitly, but the few glimpses Disch offers of life in his apartment off Union Square are more terrifying than his more morbid poetry ("I love dead men, and I will engulf/ every pound you can push into me.") An excursion of a few blocks begins with "I actually managed to get out of the house." An offhand mention is made of how he can longer eat candy bars. The final post imagines starving to death after being priced out of Manhattan grocery stores. A rare journal-like entry, improperly indented and sandwiched between two poems, reads, "April 4. Another gray day. Can't find the energy to get the laundry down to the laundry room. The sciatica just won't go away."

At times, Endzone seems like a different kind of memorial, one to Naylor, eulogized by Disch in a series of poems tentatively titled the Winter Poems (many would eventually be published as Winter Journey in 2010). The six-line tantrum of "Eat Your Vegetables" shows Naylor "waiting to die with the schooled patience/ of a civilized person accustomed/ to standing in line". In "The Deaccessioning IV: Bookmarks," the dead lover is evoked through a ticket stub found in an old volume and suddenly "it was though he were there in the park,/ age 25, dying in my arms." Others are less successful. Disch makes clear that what appears in Endzone is not quite poetry but rather "[j]ournal entries or musings in an elevated language." Several almost-poems have different typefaces, suggesting they've been pasted from a word processing program, but most feel as if they were composed on the LiveJournal platform, then posted hot and fresh and reeking. In one, Disch references a typo in the post's title, leaving it uncorrected.

Comments offer edits and praise for the almost-poetry, and sympathy for Disch's personal trails. Responses to Disch's xenophobic rants are overwhelmingly disapproving yet muted, perhaps best represented by, "I'm hesitant to say anything, but..." Referencing his extensive travels, Disch states "[a]ny xenophobia you may discern in me has been earned." Yet his tirades seem to reflect the insular viewpoints of The Rush Limbaugh Show or The Drudge Report, the latter of which Disch often references. While Disch was a (very) vocal atheist, he singles out Islam routinely for its supposed barbarism. He suggests the international community should "[l]et everyone in Darfur kill everyone else" and that Muslims should be made to take segregated flights. It is difficult to tell how much of this is merely provocation. Instead of the then-embryonic wall between Mexico and America, Disch proposes to "kill [immigrants] as they enter"; it is hard to take this as anything but Swiftian. His hatred of George W. Bush is expressed loudly, and his short stories "The White Man" (2004) and "The Asian Shore" (1970)—in which a visiting American author gradually transforms into a Turk—reveal a far more complex portrait of xenophobia than Endzone would suggest him capable of.

Most industry professionals knew better at this point than to engage with Disch, especially on his home turf. As Patrick Nielsen Hayden, one of the many who stopped reading Endzone in disgust, noted in his obituary, Disch "played the game of literary politics hard, and sometimes lost badly." Disch started referring to himself as God in late 2006, a conceit from his final novel The Word of God in which the authorial voice declares, "All my justice shall be poetic." In Endzone, Disch gloats over the death of the critic Algis Budrys and mocks his former editor Linda Rosenberg in verse. Philip K. Dick is encouraged to "rot in hell," ostensibly for Dick's 1972 letter to the FBI claiming Camp Concentration contained coded "anti-American" material. Disch crows that he will never allow the republication of The American Shore, Samuel R. Delany's book length exegesis on a single story from 334, due to perceived attacks on Disch's career as SF critic.

One of the few who never gave up on Disch was John Crowley, author of Little, Big and The AEgypt Cycle, whose blogging on LiveJournal directly led to Endzone. In the comments Crowley constantly challenges Disch's belief in his own bile ("What's sweet about your gall is how evenly it is sprayed about.") and in doing so raises questions about whether he is interacting with Tom Disch the man, or tomsdisch the authorial voice of Endzone. On one of the rare occasions when Crowley blows his top, he cuts through the layers of performance and irony: "I suspect it's YOU who enjoy the spectacle of ruination and abomination..." Either way, it is Crowley and his arguments for compassion and kindness which offer what little succor there is in the proceedings.

As Giovanni Tiso has written, "...a blog doesn't become a text until somebody puts an end to it." Since a blog can always be modified, it is never "quite fully in existence." (Disch cleared away posts and poems "if not exactly deadwood not really deserving posterity's attention.") Ended blogs are thus like dead authors; they are ready to be explained. Tiso posits destruction as an antidote. Disch, however, left Endzone undeleted; this is not a case of Max Brod refusing to burn Kafka's papers.

The central impulse behind the rapidly growing use of social media memorials may be to offer survivors an ongoing connection with the dead. Facebook encourages users to post on the memorialized pages of the dead. The post-mortem Twitter service LivesOn adapts "to the living users' habits and preferences, eventually becoming their digital twin" so as to perpetuate their "digital legacy." Both approaches ensure that the deceased continue to pop up in the timelines of the living. Disch's penultimate post imagines an anthology composed of missives to authors "safely dead." Post-mortem, the comments began to fill with letters to Disch, mostly expressing the frustration that their authors will never meet Disch. The gulf between writer and audience presented is vast. Any sense of connection Endzone offers has to be gleaned from its static texts; Disch is indeed safely dead.

The rhetoric of social-media afterlife agencies can sound downright Kurzweilian; their proposed replication of human consciousness in the digital is certainly more basic "than a frozen head," but the same impulse is there. Endzone did not prefigure this trend but rather allowed its author to engage with a literary form he did not quite understand, one just as flawed and imprecise as more traditional forms. In this, Crowley’s suspicions are correct: the tomsdisch of Endzone, the miniature icon with its blank humanoid face, is no more Thomas M. Disch than the authorial voice of The Waves is Virginia Woolf. We would do well to remember this when viewing the memorial Facebook pages of our loved ones or imaging the analyzation, by humans or bots, of our Twitter timelines after our own deaths.