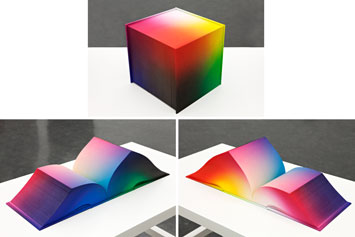

Tauba Auerbach, RGB Colorspace Atlas. (2011)

I once heard Leon Botstein, the President of Bard College, compare books to stairs. “They’ve invented the elevator,” he said, “but sometimes you still walk up.” There are countless discussions on the future of the book—they are picked up in magazine feature articles, in trade conferences, and in academic roundtables—and in all of these, the future of the printed word seems certain: in a generation or two, print will become obsolete. In this age of changing habits, if print is the stairs and screens the elevator, then what could the escalator be?

This moment in time, and the awareness of the possibilities electronic publishing grant, affect the manner in which we relate to texts in a way that is under constant scrutiny. But images prove to be a different problem. The separation between text and images has a long history. In fact, images have posed a challenge for publishers from the early days of print—be it the cost of printing them; the payments for illustrators, photographers, and designers; or simply contextualizing the images and their relation to the text—but they have become crucial to our understanding of texts. When the Illustrated London News, the world’s first illustrated weekly newspaper, began publishing in 1842, the relationship between the text and the engraved images in the paper was such a novelty that it took the weekly about a decade to stake a hold in that era’s news distribution channels. Once it did, it became one of the most widely circulated newspapers in Victorian Britain. The marriage of text and the engraved image marked a new level of fluency in communication via images, which does away with staples of early print day, even though the separation between image and text lasted for many decades later, and can still be traced today. (Think, for example, of the plate pages, where color images were glued onto the paper, so that the book or magazine would be printed in black and white, adding the color pages later in a way that saves money on printing, but also generates a wholly different relationship with images. These are often associated with encyclopedias, but a large number of artist’s monographs retained this design even after color printing became widely accessible, creating the odd text-image relationship where an artwork is described to the most minute detail, with a comment in parenthesis directing the reader to “color plate 3,” where the mentioned piece could be seen in glossy print.)

The generations to come of age in the days of digital publishing and reading on screens have a much more complicated relationship with images. The human eye-brain system is capable of reading a large number of high quality images in a matter of split seconds, and this, alongside the hand-eye coordination—think about the pleasure of a touch screen versus inky newspaper pages—is rapidly developing to mirror our changing habits of consuming information. So much so that the contemporary heightened sensitivity to the way we read images can lead to an ability to, at times, ignore the quality of the images when inserted into a text, the way our brain glides over a typo in the flow of reading. The way we read images online is only one thing these magazines deal with in the process of publishing, but it is surely an element that dictates a large portion of the reading experience of these publications.

The first issue of the Illustrated London News (1842)

The endless discussions on the future of print bring up the contemporary fluency with images on a regular basis. Aside from the fact that digital publishing is often cheaper and always easier to disseminate, many consider the role of the image in digital publishing to be a key aspect in the contemporary experience of reading. The benefits of handheld devices are considered time and again, especially in relation to embedding a variety of image formats: slideshows, moving images, animated GIFs, and so forth. A number of start-ups like Flyp bring screen-based reading beyond the initial technology, and enhanced e-books are quite widely considered to be the next major option offered by electronic reading devices.

Whereas some of the aforementioned key possibilities that publishing online presents may seem so pertinent to contemporary art publishing, they also bring up a number of crucial issues in the relationship between the screen, the text, and the image. In the past few years, contemporary art publishing has had to somehow consider all of these questions—be it print publications that have to strategize their web presence or online publications that need to carve out a place for themselves in the web’s infinite possibilities for distraction. Taking into consideration a number of web-based contemporary art magazines, I asked editors to answer a number of questions about the way their editorial lines react to the possibilities and restrictions of the internet environment. Questions considered things like what online distribution offered, the economies of attention on the internet, sourcing images online, and finally, the relationship between print and web-based media, especially considering current tendencies of online art publications to come out with print readers.

Distribution: The Internet’s Nuts and Bolts

Mousse iPad Screenshot

“Intention follows a platform that you can deal with and afford,” says Mousse's Head of Publications Stefano Cernuschi. Mousse is printed in newspaper form, but also has extensive online presence and recently launched a dedicated iPad app. The distribution of print publications follows certain sets of rules—perfect binding, for example, helps—and a number of print publications utilize the internet as another distribution platform. Artforum and Frieze, for instance, upload each issue’s table of contents but only make a number of articles in each issue available online for free, thus enticing readers to buy the print magazine. Frieze uploads all older content, whereas Artforum has a unique website too, which includes web-only features like certain reviews and the infamous Diary section.

At the early days of the internet, users became accustomed to getting things for free, content especially, but once the first popular sites introduced paywalls, many followed and many will trail. Online magazine Triple Canopy recently introduced a membership system, asking its readers for $3 a month; the magazine will still be freely accessible to non-members, but a system of remuneration is indeed being considered, a complex idea based on a notion of community: That readers will pay for what they can get for free because they would like to support the magazine. So what about Cernuschi’s “platform you can afford”? Clearly, publishing online comes to a fraction of the printing costs, which is one of the obvious reasons to go online. Another is distribution. While going viral on the internet is still a process that is a mystery to many (not to mention the example of the somewhat unexpected online popularity of cats), web readership, even if murky and somewhat untrackable really, can be a constant surprise that is inexistent in a print magazine, even when considering the idea that a print product might circulate between more than the one person who pays for it at a given store. And with online readership comes the new idea of participation. In “The Journey West,” his editorial and declaration of intent, Thomas Lawson, the Editor-in-Chief of Los Angeles–based online magazine East of Borneo, explains that the magazine’s “genesis has been long and deliberative: several years of thinking past the delights and constraints of the printed page, and one very intense year of thinking through the actual possibilities of current online publication.” [1] One of the publication’s stated intents is to build up an ongoing archive about Los Angeles and its cultural scene, and one way East of Borneo found to do this is incorporate its readers. Thus, readers can upload content to the site, contribute texts and source material, and partake in the construction of the site as a resource. These examples take the idea of the dated notion of web 2.0 user-generated content to a level different than Facebook, to use the obvious example. While Facebook makes its users work for it, they do not partake in a larger Facebook community (in fact, the social network parcels out users’ sense of community for them: a school attended, a workplace, etc.). What these publications do is harness the user-generated labor and value (monetary or cultural) in order to create a sense of public.

What We Pay for Attention

The internet gets confusing at times. We consume enormous amounts of information online, the origins of which we often can’t point to, except for in our browser’s history. Publishing online seems like such an obvious choice—it’s cheap, widely accessible, and so “of our time,” to paraphrase Baudelaire’s il faut être de son temps—but it also means that online publications are continuously fighting for the reader’s attention. Online attention is a constant battle. Apart from the traffic of a site, web analytics also measure how much time a given person will spend on this or that website. Five minutes is not bad at all. The economy of attention online is radically different than anything known in print. “Though we all spent hours each day scanning screens for information, what on the internet did we actually read?”[2] Ask the editors of Triple Canopy, whose (much repeated) mantra is to “slow down the internet.” Text has a built-in duration: we take a few milliseconds to recognize words; being image literate also means that even those seconds may seem like much. “Slowing down the internet” seems like one way in, both textually and visually: “Our thinking of images in relationship to economies of attention is no different than how we consider writing,” says Triple Canopy’s Hannah Whitaker. “The photographs that we publish might require more attention and consideration than others online. We cater to a readership that accepts expending time and effort on a piece.” The process of contextualizing online images, among the amazing diversity of the web, takes time. Demanding that the reader spend this time with the magazine is in fact quite refreshing and may push the viewer to, indeed, read online.

Another possible answer to the question of what content online do we actually read is built-in to mobile devices’ interfaces. Ironically enough, even though mobile devices are supposedly designed to keep us company in transit (even considering the fact that Apple now advertises the iPad as a handheld device meant mainly for people who tend to sit on the couch most of the time, and don’t want to walk over to their macbooks), the relatively new idea of apps actually introduces a new sense of undivided attention online. iOS, Apple’s operating system, does not really allow for simultaneous use of two apps. The result is that while on our computer we always have another tab open on the browser, another program open in the background, or another memo blinking on the calendar view, when we use the internet on our mobile devices, we focus on the app we are using. Reading the New York Times on its dedicated app doesn’t allow for a quick change to look at the new email that just came in without leaving the newspaper app and switching to the email one—a decision much more conscious than that of switching tabs, for example. The iPad, iPhone, and other handheld devices also rid themselves of the cursor, so that their users are not really directed anywhere anymore. This is an interaction that designers are apparently much challenged by—a way of looking at a page that is closer to reading print. Where the cursor was a stand-in for the user’s finger, the finger is now used again, and the eye follows a part of the body rather than an element embedded in the screen.

Now that such a screen-based platform exists, how to use it? “No one reads Mousse from cover to cover—and I’d imagine the iPad app is the same,” says Cernuschi. “When it comes to attention, I think it is also a derivative of the way in which information is presented graphically. We try to work with reduction—when the quantity of textual and visual content you can upload is limitless, it gets quite difficult—and we didn’t want to be a Wikipedia kind of experience. We use one font across the range, keep the text simple, and try to focus on the images.” Cernuschi moves on to explain, “In a way, we’re all children of the iPod.” The act of using a touch screen is so pleasurable, such a radically different movement, scrolling with one’s finger rather than flipping through paper, that it changes the user’s interaction with the visual content. What the editors at Mousse claim was difficult in the development of the app is its boundless nature. In print, every addition might be translated to printing costs—so physical constraints bring about the necessity of making choices, and with it, an editorial line. Which led the editors to understand the iPad as a reading platform—“it’s still two-dimensional,” sayd Cernuschi—and so the app is not completely based on multimedia, even though it does include a number of videos, for example. But the shift from a printed copy of Mousse to its iPad app is not as sweeping as one may imagine.

The Location of the Online Image

Screenshot from Red Hook, with images provided through Katya Sander’s Hard Drive (where images accompanying the texts are automatically pulled from the web, based on each reader’s hard drive as well as key words and themes in the articles).

The Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College recently introduced Red Hook, an online journal for curatorial studies. Red Hook’s relationship with images is one example that truly considers the magazine’s online existence and presence. In the editorial for the first issue, its editor Tirdad Zolghadr states, “Although this journal will certainly attempt to do justice to opportunities for revisiting traditional hierarchies between image and text, it will be careful not to imply that language is diminishing in comparative importance, or that the online sphere can heal old wounds. On the contrary, the idea is to highlight and complicate an enduring hegemony in the hermeneutic food chain of online circulation.”[5] One way to complicate those old wounds Zolghadr mentions—the text/image divide being a painful one—is the magazine’s particular approach to images. Issue 1 is fully illustrated by one artist project: Katya Sander’s Hard Drive, where all images accompanying the texts are automatically pulled from the web, based on each reader’s hard drive as well as key words and themes in the articles. Red Hook does not have an image editor, but rather, it recruits artists to think through and further explore the magazine’s relationship to images. Zolghadr further explains, “This was not meant to delegate image-editing responsibilities, at least not in a lazy and self-effacing way, but to avoid putting the cart before the horse. In a curatorial context, the specific mode of knowledge production I find the most productive is one that is developed and tested via an imbrication of theory and practice, saying and doing—preferably though not necessarily in tandem with artists. When Sander was invited to partake in the first issue, the instrumentalization of images in a publication context—and the lack of online signposts that traditionally steer this kind of process—was a cornerstone of the conversation.” The resulting project is refreshing—I haven’t seen an image repeated twice in the issue—, and also confusing—the images accompanying the texts on my screen varied from milk bottles in a crate to demonstrators in Eastern Europe, and the link to the images' original contexts may be an interesting addition, but one that can be distracting, in that it sends the reader back to the wilderness of online image repositories, asking him or her to make sense of the images once those no longer have any relationship to the original text where they were encountered. It may be an interesting exercise in decoding images, but it’s also a losing hand in the battle on online attention.

From Print to Screen and Back Again

(from print to screen):

“When Triple Canopy was founded,” its editors recall, “the content was bounded in a box and you ‘flipped’ through the pages as you would a print magazine. We hoped that this page metaphor would underline our relationship the kind of serious content more associated with printed media—to (as we’ve often stated) ‘slow down the internet.’ In the end, this format proved to be limiting and, ultimately, anathema to our mission to consider the internet’s specific qualities as a form. We eventually redesigned the magazine and scrapped the page in favor of horizontally scrolling columns. In this new format, the relationships between image and text are more fluid. A given image is seen in the context of text that comes both before and after it and the bounds of the magazine are constrained by the size of the browser window and by the computer's screen size, or are in other words, set by the reader.” What this description exemplifies is the way in which the design of web-based art publications considers itself in face of print. The design of numerous online art publications considers the history and tradition of print in a myriad of nostalgic, more or less skeumorphic ways while bringing up old fears that reading habits are almost unchangeable. Even though Triple Canopy is quite unique in its horizontal scroll, it shares a similar attention to the print versus screen reading experience. One interesting element of which is the persisting presence of the table of contents in web-based publications: as part of the linking culture of the internet, the links to the other articles in the same issue are visible across the board. Another aspect of online culture that these publications have picked up on is tagging by subject and “for further reading” tabs, which try to anticipate the reader’s interests according with the stated themes of a given article.

Where do images fall within these design questions? Triple Canopy’s editors attest that, “One issue that came up in the transition between the two formats [the flip box and the horizontal scroll] is that you lose the impact of a photograph when it slides onto the page rather than appearing in an instant. But, we do have a full screen function for those images that require more white space around them.” Most other publications have a vertical design that introduces images as sidebars or directly aligned in the text, mainly without linking the images out or allowing for a full-screen viewing option. I would argue that this is another remnant of print culture in the digital sphere. Considering that the content of these online publications generally sways toward the theoretical more so than the glossy-print-magazine type, this brings forth a relationship with images where they are more illustrative and do not require a very specific—say, full-screen view—attention. Mousse’s Cernuschi says, “We have a complicated relationship with images because we print in a newspaper format but we’re a fine arts magazine. So we flirt with this idea of inaccurate reproduction in the first place. The priority with images is not exactly to ‘get it,’—for that, I think paper printing is a very honest filter: it looks cool, but not really good. On the screen, images look much better. I would much prefer an image printed on appropriate paper than on a screen, but that’s usually not the case. So for us it’s very different, especially considering that we can reproduce media. You develop a so-called video still aesthetic on paper.”

(and back again):

When considering the multiplicity of valid reasons why so many contemporary art publications choose to go online, it is quite astonishing to see how extensively they consider print as an option.[6] Take e-flux journal: It was launched by an organization that made its name and brand by being the first to give a very specific—and much called-for—online service. The journal, too, started in 2008 as a web-based initiative; but it soon introduced a series of readers in book form, published in collaboration with the Berlin-based publishing house Sternberg Press, and a print-on-demand system that allows readers and institutions to print out full issues followed. e-flux journal’s distribution system includes art institutions and bookstores around the world, who all download a PDF generated directly from the online articles, in what is a nod to ideas of open circulation and transmission of ideas on the internet, only in an offline, widely distributed but still independent, version.

A number of other web-based magazines seem inclined to follow e-flux journal’s direction. Triple Canopy published a first reader, Invalid Format, in the end of 2011. The cover of the book reads “Volume 1”—and indeed, the reader only covers issues 1 through 4, bringing up the amusing question of whether Triple Canopy will forever chase its own tail: Will the book-form readers catch up with the online journals? And Red Hook editor Zolghadr states that publishing a reader could be one direction for the magazine, but according to him “we’re taking these things pedantically seriously, and are in no hurry to expand to other media just yet. The journal will first need to take its time to familiarize itself with its technical and institutional specificities.”

So what does it mean to print out the internet? In the introduction to Invalid Format, the editors of Triple Canopy discuss their initial speculations as to the possible longevity of a web-based publication: “We had a sense of the inevitability of obsolescence—think of cassette tapes, LaserDiscs, Mosaic Netscape 0.9—and of the need to safeguard our work being reduced to so many broken links and 404 errors.” The idea of publishing books based on the online journal came up as a way of “artful archiving.”

Downloading, so to say, the content of these publications from the online sphere to print can also introduce new problem of design. When taken offline, the images gain a new visual character: whereas on the screen, all images are in color but are indiscernible in context (especially when linked out of the specific journal—an image used in an online publication is totally different when viewed through Google Images) and in origin, in a printed form it is tied in with the text and the design in a way that relates to the history of publishing and to our expectations as readers in a wholly different way. Take, for example, Boris Groys’s article, “The Weak Universalism,” in e-flux journal. The piece, where Groys considers avant-garde’s nondistinction between artists and non-artists, is accompanied by a number of images, like a photograph of Kasimir Malevich teaching a class, a painting by Kandinsky, and a screenshot of Andy Warhol’s Facebook page (“Sign up for Facebook to connect with Andy Warhol!”). The randomness of the screenshot may seem more intentional in print—in the print version of that issue, for example, it sits on the same spread as a still from Empire—and it loses its interconnected nature that it may have with its online home (imagine reading that article on one browser tab while keeping Facebook open in another tab). And, unlike traditional print, where a screenshot or a video still may be of visibly lesser quality than a high-resolution photograph of a Kandinsky, the printed versions of online art publications tend to retain the flattened-out, non-hierarchical nature of the image as it was seen online. But whether images printed in poor quality, off the internet, become simply signifiers or rather, an “aesthetic of screenshots,” remains with the reader.

To end at the beginning, let me bring up the question of the escalator one more time. Unlike an elevator or stairs, which can be featured in private homes or apartment buildings, an escalator is generally inherently public. It’s not the exact middle ground between the stairs and the elevator because it picks up on certain elements of both while remaining a different variant of them as a mode of transport. Like the stairs, it considers only the human body (it will barely tolerate a baby carriage or luggage); and like the elevator, it has a built-in sense of pace. It seems pertinent here that the escalator is a trope of public space—train stations, airport, department stores, and so forth. What are the needs of the escalator riders? It allows them the possibility of cutting distances short while eliminating the sense of a group that an elevator may create.

The specificities of contemporary art publishing initiatives online may echo the escalator at times, while also embodying certain characteristics of the stairs and the elevator. We are only getting more image-savvy with time, which confuses and collides the relationship between text and images. The current decade is a very particular one in the history of publishing, as it will be full of moments that will be declared to be decisive for the “fate of the book.” And maybe books are like taking the stairs—it may be old-fashioned, but still seems natural, and our brain-eye coordination is accustomed to it in a way similar to how quickly toddlers learn to crawl and walk up and down stairs. But the elevator? Standing in a slow-moving elevator seems more nerve wrecking than walking up the stairs. This is what reading an old e-book will be like one day. The need for constant reinvention in digital publishing calls for a certain flexibility, and one that online art publications seem to be offering simply by the sheer fact of their constant consideration of what publishing online means. A hybrid model of print-to-screen-and-back-again might teach us much about our relationship with images, which will define and shape the history of art and the way it is taught and written about in coming years. This might just be the equivalent of the possibility to run up or down the escalator in the opposite direction than it is heading. It’s possible, even if exhausting. But sometimes, you just want to stand there on the escalator and see the ground distance itself from you while you take in the view.

[1] See Thomas Lawson introduction-cum-editorial statement, “The Journey West,” on East of Borneo (October 10, 2010).

[2] See Triple Canopy’s editors’ article, “The Binder and the Server,” at the College Art Association’s Art Journal (vol. 70, n. 2: winter 2011), 40–57.

[3] The “wild west” of online reproduction and intellectual property rights in the internet environment is an incredibly complex subject that is currently tackled by people in many fields in a constant attempt to define it for themselves at the moment. The question of best practices for online reproduction and online intellectual property rights is too large to consider seriously here and the literature about it is slowly building.

[4] Whitaker’s introduction deals with the space of photography in contemporary society a way that the elusive terminology of “images” (therefore converting all photographs, illustrative drawings, film stills, and so forth to one all-encompassing class—which can mainly be characterized by the fact that the people who view it do not often think about those images’ origins) in a way this article could never do. See her essay, “A Note on Black Box,” in Triple Canopy, issue 12.

[5] See Zolghadr’s editorial, “Notes from the Editor,” in Red Hook, issue 1.

[6] The idea of the possible obsolescence of online media and the fact that technology seems to be developing at a pace much more rapid than the pace of editorial decision is cheekily picked up by Zolghadr in his editorial: “Curatorial education aside, a second moving target here, one that is at least as mystifying, perhaps even more so, is the new field of online publishing. This is where you get an even clearer sense of the privilege and vertigo of inhabiting a historical threshold, leading to a constant suspicion that you’re missing key conversations unfolding concurrently all around you, coupled with yet another nagging suspicion, that much of your eagerness and anxiety will be considered quaint only a few years from now.”