Introduction

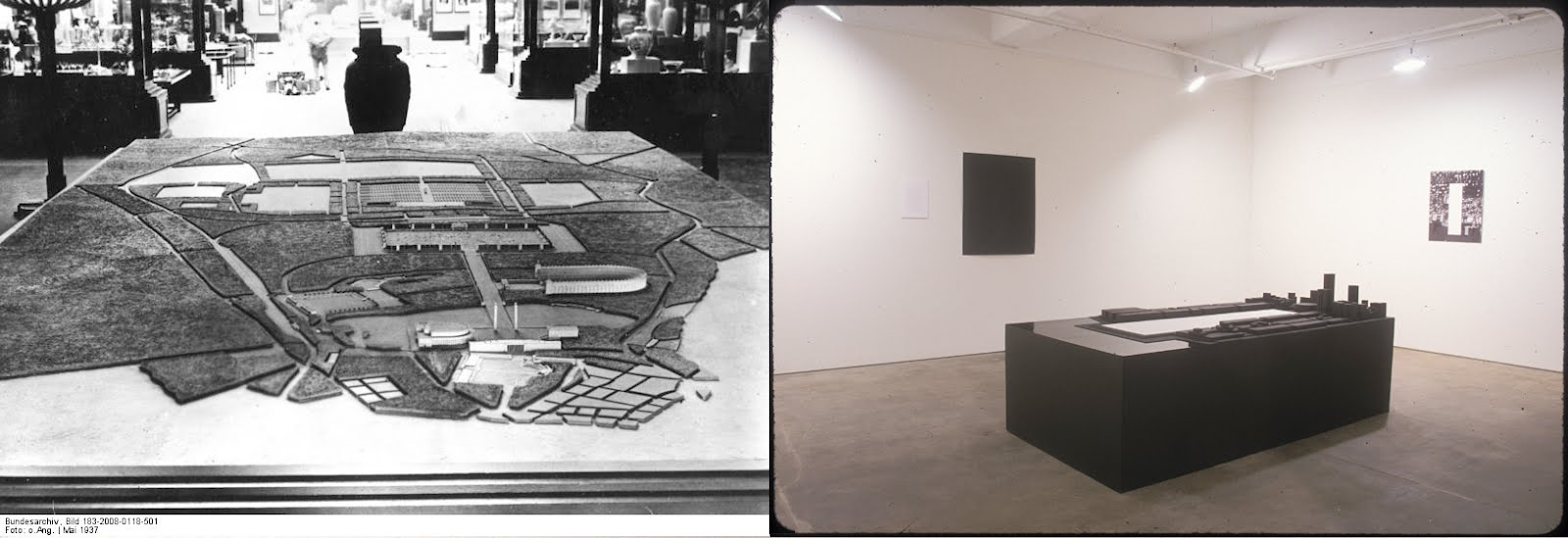

Albert Speer, Model of Nuremberg Marching Grounds (1937); John Powers, Penn Station Counter-proposal, (2001)

What happened at 9/11 of course changed the scale of all this... It became an issue about fear, and our horror at looking, as I did, out of our windows onto the buildings that were burning. The horror we had in our hearts from this, allowed us... to give up basic freedoms. I’m not just talking about the ones the papers talk about all the time, our democratic and constitutional rights, but in the way we live, the way we block our streets.

—David Childs (Chief Architect of SOM’s Freedom Tower”), Buildings and Fear, 08:20 (2007)

I am a sculptor, my work is abstract and more often than not described as “post-minimalist.” Recently I was asked to contribute a work for a group show in Hong Kong. The curatorial frame of the show is “the ways objects produce space.” Rather than contribute a sculpture and hope for some sort of latter-day phenomenological experience between ‘object’ and ‘subject’ however, I suggested revisiting an urban design project that I had not worked on for over a decade. Eleven years ago I made a modest proposal to create a series of three massively flat and empty superblocks (two in New York and one in Washington DC). I last showed these proposals as three large architectural site models, just six months before September 11th attacks. Because my proposals seemed to foreshadow the 16 acre gap left in Manhattan’s grid, I was urged to revisit the project. I didn’t, not because I didn’t feel I might have something to contribute, but because I was struck dumb horror. I refused to speak publicly about the project, and although the original show of models had been based on a long essay on the subject of art and public space, I stopped writing for years. Anyone familiar with myblogwill understand that this is not my usual MO. But looking back I am now very glad I shut up.

Most of what was said about architecture in the immediate wake of the attacks struck me as tone deaf, some of what was said by artists was unintentionally cruel.

That is not to say I didn’t take interest in the site and the conversation around it. I followed the competition to choose an master plan, and still feel Sir Norman Foster’s unapologetically hard edged “kissing” chisels were the best of the lot. Most of what I saw and heard however, reinforced the observation that had inspired my proposals in the first place: the widespread inability to know the difference between what can and cannot be changed when it comes to architecture. By wide spread, I mean architects, politicians, critics and loudmouths at parties. Even after Modernist architecture’s fall from grace, the expectation is that big challenges must be addressed by massive projects, and that symbolic meaning trumps straight talk (observe Libeskind vs Foster).

While I sympathized with architect’s desire to respond to the attacks, I did not understand their responses. Architecture isn’t a symbol (that was the hideous confusion the attackers made), it is an expression; a concrete expression of an idea, an ethic, a desire. Modernists plazas are often characterized as “fascist” — the idea being that they are symbolic projections of power. Architects seldom, if ever, discuss lawns, park benches, or flower arrangements as expressions of power. Looked at as concrete ethical expressions, rather than symbols, we can begin to see these things for what they are: impediments, barriers, place holders, and dividers.

I: Double Zero

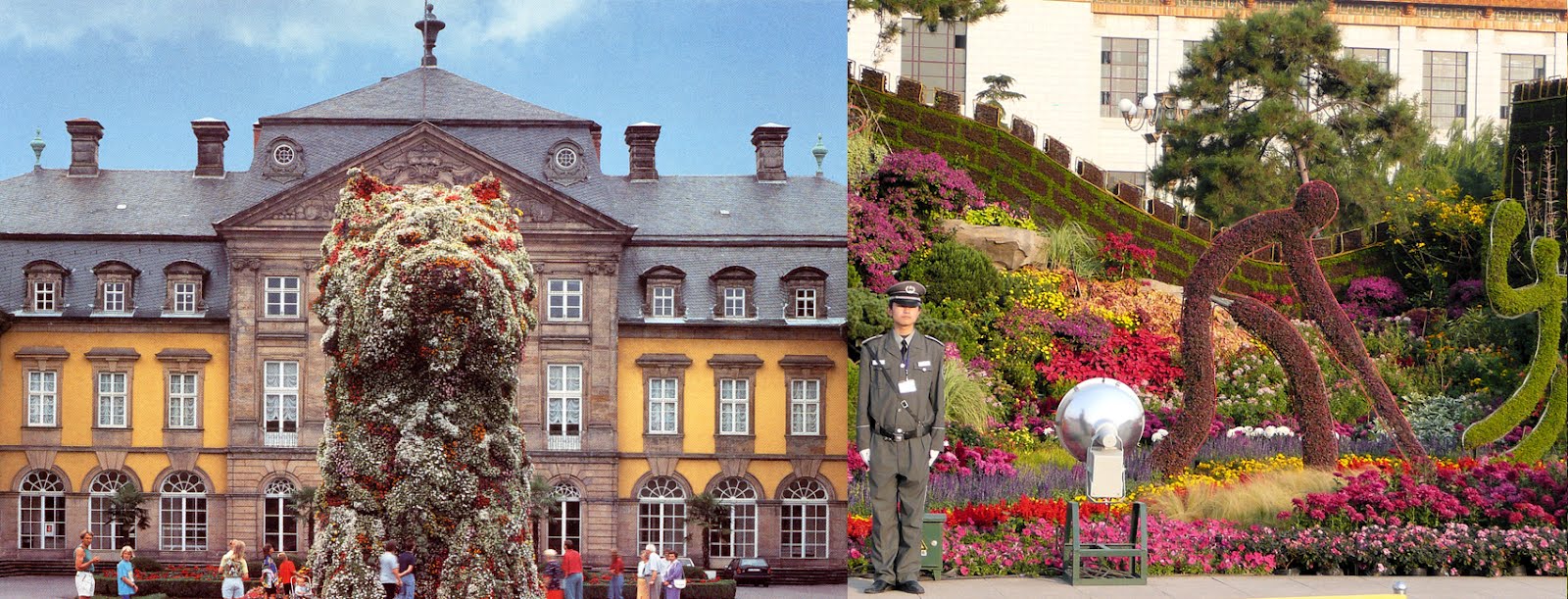

Soft Power: Jeff Koons, Puppy (1992); Tiananmen Square Olympic flower arrangement (2008)

For the show in Hong Kong I ended up showing recreations of my three original counter-proposals, and a fourth proposal that has been gestating for almost a decade, but has suddenly taken on new relevance. I proposed building nine “Freedom Towers” arranged in a tight grid formation and completely occupying the available open space of Tiananmen Square.

A decade after I proposed paving flat large portions of New York and DC, I want to “occupy” Tiananmen Square with a formation of Freedom Towers. These may seem like two very different projects and two very different political contexts, but in fact they are the same. In 2001 I was suggesting that we had lost an important variety of public space and that our cities and our republic were lessened by that loss. That in the 40 years since the civil rights and ant-war protests of the 1960s American authorities have altered the landscape of our cities –— through changes in the rules that concerning public assembly (a process Naomi Wolf calls “overpermiticisation”), but also through bricks and mortar construction. Our public space has been “developed” out of existence.

In the wake of the massive protests in Wisconsin, the “Arab Spring,” and the Occupy movement in New York (and everywhere else), it feels important to once again raise the question of public space as a built environment. Rather than continue to argue that we build a new kind of space here, I am suggesting that we imagine what it would mean if we exported our current development schemes to other countries; to imagine them as the work of foreign regimes. What if the National WWII Memorial, with its heroic Speerian colonnade, sunken plaza, and ground-covering fountain, had been built in Tahrir Square rather than midway between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument? How would we feel if Russian authorities were to announce the construction of a large Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim be built over, Bolotnaya Square, the site of last December’s ballot-rigging protests in Moscow?

To mashup SOM’s Freedom Tower and China’s Tiananmen Square may, at first glance seem arbitrary, but it isn’t. Both New York’s Ground Zero and Beijing’s “Zero Point” are symbolically loaded sites. non-mainland Chinese associate Tiananmen with the 1989 pro-democracy protests, but for the Chinese it was already a site loaded with meaning when protesters chose that space to take their stand. In his book Remaking Beijing, the author Wu Hung describes the formation of Chinese end of this symbolic East-West axis:

An unlikely coalition of left-wing Chinese architects, Soviet specialists and Western-trained urban planners of a modernist bent, argued that the capital could fully realize its symbolic potential only by locating the government in traditional Beijing. A crucial argument made by this second group was that, because the country’s founding ceremony took place in Tiananmen Square, this local should logically be the center of new Beijing... By relocating ‘zero’ to Tiananmen Square, the birthplace of the People’s Republic, the city would acquire a new identity and a vantage point for its architectural restructuring. Beijing’s centre of gravity would automatically shift southward, and the avenue running east-west through the square would become its new axis.

Hung’s book discusses what he calls “soft monuments;” large scale flower arrangement and other temporary displays. Unlike a “'hard monument' from the previous era that commemorated history and demanded faith, a 'soft monument' of the 1990s and 2000s is deliberately short-lived and goal specific.” Now according to Hung, the intention is to displace dissent, depoliticize the space: “Instead of empowering the Chinese people to carry out political or military campaigns against domestic and foreign enemies, images in the Square now express citizens’ happiness and unification.” In other words, the world’s largest public square is now inhospitable to protesters due to strategically arranged flower displays.

The Chinese could learn something from the public/private partnership of American real estate developers and political authorities. One World Trade Center, or Freedom Tower, is the office building replacing the site’s fallen Twin Towers, and the latest example of American public/private political double talk – an expression of freedom that is in fact a commercial property where employers and landlords have final say on what will and won’t be permitted, what can and cannot be said. Additionally, the building itself is a fortress; an architecture of fear embedded within an urbanism of political self-loathing.

In 2007 the architect of the Freedom Tower, David Childs, gave a talk appropriately titled “Buildings and Fear.” I attended because I wanted to know how an architect who had designed a skyscraper built over a 200’x200’x200’ cubic volume of uninhabitable bomb-proof cement base, dubbed a “Freedom Tower”, would explain himself. I was impressed. Childs turned out to be a smart and self-reflective designer. Although he justified his disguising the building’s fortified nature with a façade of “prismatic” glass because the glass would act as a kind of sensor if a blast did occur… Which seemed a bit slippery to me; what impressed me is what he said about the post-9/11 culture of cement barriers and security booths:

I’m chairman of the Commission of Fine Arts, and I’m very much worried about what’s going to be happening to our image of democracy... you can imagine of course right after 911 all this kind of temporary facilities went up but it wasn’t very long until the final ones came into place, and they’re not much better... So this is a real problem of how we can control this and I found to my surprise that the leaders, the head undersecretaries would come before us and they were reluctant, when we would say “Well, can’t you design this in a way so that you don’t see it?” And well, in fact, many of them wanted to see it. It was a status symbol. If your agency got more of this kind of junk out in front of it you were obviously more important, and so they didn’t want to do it. They really thought you should see it. And this is an attitude that many of the people trying to deal with securities and cities have. And by the way I should say that many of the consultants that we work with are more than reasonable. But many are also fear mongers. They say that we have to do this kind of closing down in order to make it safe, and in order to make it safe it must look safe. So it’s not a question of hiding things as probably more expense, but just showing the kind of structures that you put up front to block car combs, and other things, or to look menacing in themselves.

The idea of this mashup dates back to the decision to hold the Olympics in Beijing. There was a well-founded anxiety that the Chinese authorities would take the opportunity to build the “Olympic Village” in Tiananmen Square – thereby making a large-scale protest impossible to effect. While that never came to pass no one could predict the massive restructuring of the city that did take place. In addition to heroic structures by International Starchitects that now dot the city, 100,000 families were relocated to make way for new construction for the Games (see Brazilian Games).

The opportunity to show in China, the fact that the Freedom Tower is nearing completion, but also the fact that the weather is warming and we can expect fresh round of protests, gave this shelved project new relevance for me. However, the true genesis of this project, of these concerns, dates back to my earliest political memories.

II: SHAME

Art Workers Coalition (1970); Public Radio freelancer Caitlin E. Curran was fired for appearing in this picture (2011)

My father tells a story about a friend of his, who, during the 1960s would drive around with an “all-purpose protest sign” in the trunk of his car, so that whenever he happened on a protest he could easily join the crowd, no matter what the subject of the protest happened to be. His sign simply read “SHAME.” I remember hearing the story as a kid, and finding it confusing. I got what my father wanted me to get: I understood why his friend’s solution was funny and smart. The part of the story that was confounding was the idea of protests being something you might just “happen upon” while out for a drive.

I knew immediately what my Dad’s friend’s sign would have looked like – a stick of wood with a large card stapled to it. I could imagine what my dad’s friend might have looked like: either a well-groomed black man in a suit or a slovenly youth with long hair and silly cloths. As a child I was familiar with protests only through historical footage of the civil rights and anti-war movements I would have seen on TV. I don’t have a single memory of ever having randomly driven past a protest of any kind. My father explained that they used to happen all the time. That people had been more active – once upon a time, in the “60s” – but not any more. As for why, I never got a straight answer from my father or anyone else when I was growing up. Things had once been one way and now they weren’t that way anymore.

In high school, I followed a group of friends to a protest (No Nukes, I think). I remember dressing up. I didn’t have long hair, but wanted to show I was “radical” or at the very least “committed” – I think I wore a white bandana, maybe all white. I’m not really sure. The image is more an abstracted feeling of embarrassment, than any clear picture. My friends took me to stand with a small crowd outside a nondescript fence. It was lame. I knew that this was not how it was supposed to be. This is not how it had been for my father when he marched in Selma Alabama with Martin Luther King, or for his friend, who marched with everybody else. Something was missing, something in me, and the people around me; it was a disheartening realization because I had no idea what it was that missing.

Five or six years later, I was hitchhiking down Highway 101 from Seattle. I got as far as San Francisco when the Rodney King verdict was handed down and the LA riots began. Rather than wait out the unrest in SF (where smaller, less spectacular, riots had broken out), I decide to continue slowly hitchhiking down coast, camping and avoiding trouble. It was a dumb plan, but I was lucky. I didn’t get into any big trouble, but I was luck enough to have a little trouble find me.

I had hardly gotten out of San Francisco when I was picked up by two young political activists who were rushing down to LA to see what “good,” if any, could come from the confusion (they worked with a group that spoke to inner city youths about environmental issues in relation to income and race – good guys). They convinced me I should go down with them and see what was happening. The three of us talked politics the whole way down the 5. I ended up arriving in LA the second night of the riots. We could see the fires as we headed into the city.

I’ve always wondered what those guys did when they got there, but “...something something about a girl,” we parted ways that night. I spent a few days moving around LA by myself on foot, observing the city in lock down. I remember finding it interesting that in a city dominated by cars, the police were able to contain and close down the possibility of riots by closing all public parking. Without a place to park their cars Angelinos couldn’t congregate in large enough numbers to intimidate the police.

The next major stop on my trip (being stranded in Barstow doesn’t count) was Austin where I stayed with a young Palestinian architect and his wife, an American born political organizer. These friends, both politically active students at University of Texas, were keenly aware of architectural space and protest. They were very interested to hear what I had seen in LA. I told them about the parking, and they told me how in the 1960s students at UT in Austin had gathered in large open spaces on campus, formed into large masses of protestors – too large to be controlled by police – and once these masses had formed, they moved.

Adjacent to campus, and politically far more symbolically potent, is the Texas State Capital. There, at the more politically loaded symbolic space of the Capital “steps,” the protestors were able to make their voices heard and their anger felt. My hosts explained how, in the intervening years, the campus had been altered with plantings, benches and berms; impediments that to made it impossible to gather large groups. The lack of a safe and unrestricted open space to ‘build mass’ made it much harder, if not impossible, to create the ‘mass movement’ needed to overcome the authorities’ understandable desire not to allow protests on their steps. I never considered decorative plantings and benches as anything other than a positive addition to the urban landscape. I now saw them as subtracting from public space – as a division that acted to reshape what could and couldn’t happen within pubic space.

My friends told me that UT’s quad wasn’t the exception; it was the rule. That since the great campus uprisings of the 1960s quads all around the country had been divided by plantings, earthworks, and hardened features. Likewise American cites had altered public spaces and rules for who could use them and how. The small, lame, and obviously ineffectual protests I had taken part in – even when the stakes were high, as in the case of the first Gulf War – had been engineered to be lame.

I have never taken part in a riot, or, at that time, even a large protest, but I did know what it felt like to move with a large crowd. I had run through the empty streets of the Loop after a Fourth of July fireworks display with a thousand other drunk and high Chicagoans (awesome). I’d slam danced at rock festivals, and moved as an unstoppable body with hundreds of others at sporting events and concerts. I knew how empowering those experiences had been. Those memories stand out above my day-to-day life, they are still exciting to think about years later. So I could imagine how much more potent it would be, had they taken place within the context of a political protest – that those sorts of feelings of power must have supercharged the large protests I had watched in PBS documentaries growing up.

As a teenager in the 1980s I heard a lot of stories about the glory days of the 1960s. The moral of those stories always seemed to be that giants had once walked the earth, and that my friends and I were a diminished race of weaklings. The young people of the past were manifestly more engaged than my generation; my peers and I lacked some essential part (spine, heart, spirit) that our elder’s had somehow had in abundance.

The story my friends in Austin told me was different, it pointed to the fact that my friends and I hadn’t lacked some ineffable quality, but that the conditions on the ground had change. We weren’t radical as a group because were weren’t given the space to move en mass. To feel empowered as a group, to be physically radicalized by the feeling of standing up to an authority and seeing that the authority could be swayed, or, if need be, physically intimidated. The LA riots reordered the ways I looked at cities, especially public spaces. Rather than work towards a healthier body politic, American authorities had altered the body to make it easier to control. I was born into an intentionally hobbled commonweal.

III: The Rhetoric of Power

Robert Morris, Mirrored Boxes (1965); Rodgers Marvel Partners, NoGo bronze bollards (2006)

In 1995 I moved to New York to study art. One of the concerns, I learned, that had shadowed minimalist art during the 1960s is that those plain gray plywood boxes degraded aesthetics. That there was a danger that once we, the public, began accepting those “objects” as art in museums, what was to stop us from looking at cement blocks on city streets as art as well? In 1966, the sculptor Robert Morris observed “The total space is hopefully altered in certain ways by the presence of the object. It is not controlled in the sense of being ordered by an aggregate of objects or by some shaping of the space surrounding the viewer.” And asked: “Why not put the work outside and further change the terms?”

As I studied art and learned about the sometimes dry, abstract, and even algebraic ways the space around minimalist art has been thought of (I am not referring to Morris here, who’s sardonic and smart writings I admire, but a lot of his peers and countless imitators who took themselves far more seriously). I was observing the qualities of space in the city around me. Shortly after arriving in New York I walked past a small protest near Washington Square. The protesters, who numbered in the dozens, had been hemmed into to small pens by the police. While many of the kids seemed to have dressed for the part, no one carried a placard or brandished a bull horn like the protests I had grown up watching on public television documentaries. I remember thinking that they didn’t have the room needed to be truly radicalized; that mass movements require both greater mass than they were allowed and greater movement than they were allowed.

My interest in minimal art might have been a passing phase in my development had it not been for an essay called “Minimalism and the rhetoric of Power” by the feminist art historian Anna Chave. It is a remarkable and deeply critical piece of writing, and unlike the essays I read that defended and justified minimalism in terms of phenomenological encounters, and alienating confrontation, Chave’s ideas made sense. Rather than surround the work with an intellectual Rube Goldberg device (phenomenology) she “interrogated” the associations made by artists to images of power – many of them violent and cruel.

Chave isn’t perfect. She was harshly critical of the minimalists on a personal level, to a degree I find unfair. She was even mean spirited at times, especially in the case of Robert Morris, who I did my graduate studies with. She also proposed that masculine power can be displaced by some female alternative, which she dubbed “a capacity of nurturance.” I find this brand of feminist utopianism as wrong headed as socialist utopianism that set men’s minds aflame in the 1920s and 30s, or the brand of neo-liberal utopianism the GOP is so enamored with at the moment. Michel Foucault (who Chave aims to counter) had it exactly right:

I don't believe there can be a society without relations of power, if you understand them as means by which individuals try to conduct, to determine the behavior of others. The problem is not of trying to dissolve them in the utopia of a perfectly transparent communication, but to give one's self the rules of law, the techniques of management, and also the ethics, the ethos, the practice of self, which would allow these games of power to be played with a minimum of domination.

I met with Chave in early 2001. By then I had been making abstract art for six years, studying with Robert Morris a three of those years, and minimalism, via the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial and the Oklahoma bombing Memorial, had become the semi-official aesthetic of state sponsored mourning in the US. I asked to meet with Chave because, while she argued for an alternative to power I didn’t believe in, she was the first and only person I had ever read who spoke clearly about minimalism as I saw is: as powerful and aggressive. Her essay is rightly critical of that power when it is expressed in abusive ways (she really takes Richard Serra and his defenders to task – I often wonder if his gentle and sexy Torqued Ellipses aren’t a response to Chave criticisms of his earlier work). But I had the chance to ask Chave if, like me, she didn’t find that power attractive, if she liked minimalist art. “Yes of course I do.” She told. “My ambivalence is something most readers don’t pick up on.” It was clearly something she found regretful.

I asked to meet with Chave 2001, because that March I was preparing to mount a solo show of three architectural models that made a modest proposal: that minimalist space – the large empty space demanded by minimalist art – if expressed as public space, in dense urban setting, would provide space within which a crowd could form. “Why not put the work outside and further change the terms?” Morris had asked in 1966. Forty years later my reply was to image art as Morris’ friend and mentor Tony Smith had described it: as “something vast.” And while I did not want to re-imagine power as a capacity for nurturance, I believed Chave provided an answer of sorts. That what was key was to ask, as Chave had: “who speaks to whom, why and for whom.” Transferring aesthetic attention from the isolation of the gallery to public space changes the terms from academic concerns of “embodiment” to ethical concerns of power and protest.

IV: Clusterfuck Ethics

Frank Gehry, Proposed Downtown Gugenhiem (2000); John Powers, Downtown Counterproposal (2001)

The art critic Jerry Saltz calls the “the practice of mounting sprawling, often infinitely organized, jam-packed carnivalesque installations” Clusterfuck Aesthetics. When this aesthetic is put outside, the terms become “disenfranchise” and “marginalize.” In March of 2001, I made three counter proposals for three site slated for high profile cultural development: I re-imagined each as a flat, featureless plaza. That year New York City alone had over 5 billion dollars worth of bricks-and-mortar cultural development on the boards. By “bricks-and-mortar cultural development” I mean, the Brooklyn Museum and the Lincoln Center had both proposed much needed renovations (since completed). The Design Museum and the New Museum had respectively announced their aims to rebuild and build fresh (also both since completed). Most spectacularly however, the old Post Office across from Madison Sq Garden on Manhattan’s West Side was to become a heroic new entrance to the city: Penn Station reborn, and the Guggenheim had set out to build an enormous Frank Gehry designed clusterfuck (I mean that as an honorific) on the waterfront just below the Brooklyn Bridge. Additionally, Congress had secured funding to build a heroic National WWII Memorial straight out of Albert Speer’s note books on the Washington Mall right in the middle of the space that had been occupied by the crowd who listened to Martin Luther King Jr. give his historic “I Have A Dream” speech in 1963.

Like a lot of other ambitious building plans, the Downtown Guggenheim was abandoned in the wake of the September 11th attacks. Evidently the “Moynihan Plan” to rebuild Penn Station is still in play. Unfortunately the funding did not dry up for the WWII memorial (the only one of the three I truly disliked in-and-of-itself). But I couldn’t have known that when I made my original counter proposals that March.

The Gehry Museum was part of a mixed public/private development scheme to rejuvenate New York’s waterfront. For decades the waterways around Manhattan had been little more than industrial canals and open sewers. But in 1977 Congress passed the Clean Water Act, and by the mid 1990s the city had to concern itself for the first time in over a half century with maintaining wooden piers from infestations of boring worms – a problem that pollution levels had made impossible; for decades the Hudson and East river had been oxygenless deserts where nothing could live. Probably for the first time since prudish Dutch traders settled Manhattan, New Yorkers began seriously considering recreational swimming in the Hudson, and the political response was to ring the island of Manhattan with pay-to-play properties.

The push by authorities, public officials and private developers, was to in-fill; to build a wall of Chelsea Piers and Battery Park City-like developments between New Yorkers and the newly rejuvenated waterways. I believed (and still believe), that a once-in-a-century opportunity to create a vast public space on par with Central Park was being squandered in a fit of neo-liberal profiteering.

In addition to building large-scale models of my counter proposals (two featureless superblocks in NYC, and a decked cubic fountain in DC), I wrote an essay about three public art works in the minimalist vein and I gave a talk for thirty or forty people in the gallery one evening. It’s been a while, but as I remember it was a fun night. The audience was mostly architects and artists. The vibe I remember was something along the lines of “Who the fuck are you to opine about urbanism?” My proposals looked an awful lot like retreads of Modernists “windswept plazas” – but I explained that they were carefully different. That those 50’s and 60’s era spaces had been built on raised plinths with stepped entrances – I used the examples of The Empire State Plaza in Albany, The Lincoln Center, Seagrams Building and the World Trade Center complex as examples of what I was not doing.

I wasn’t proposing a stage on which to place a building, or a complex of buildings. I was proposing spaces that could be approach from any direction, mounted as easily as one mounts a curb, and contained nothing; no trees, no grass, no benches, no fountains or facilities of any sort, just space. I pointed out to my audience that if there were to be a war, there was no place in New York City where a crowd could form in great enough numbers to intimidate police on the street, much less sway hawkish politicians watching from Washington DC. I did my best, but my audience was unmoved, there was some sense that I was being hyperbolic; some sort of Bauhaus Cassandra in an age of Dot Com Pollyannas.

To be fair, every one seemed to have a good time and the discussion was lively, but in March of 2001 war clearly seemed like a ridiculously distant possibility to be worrying over. We had sailed past the millennium’s first big crisis (Y2K?), the economy was red hot and our new conservative president was hampered by a questionable election and promised to be ineffective at worst. (One defender lamely claimed “George Bush speaks for the inarticulate.”) Our cities didn’t need open spaces; if the rumors were true, Dean Kamen had invented a personal flying device that would be unveiled later that year. Who could be bothered to worry about war? (Turned out Dean invented Segways: the millennium’s first big fail.)

One audience member spoke up to say we didn’t need to protest in person any longer; that large rallies were a thing of the past, an artifact of the 1960s. That we could now make our voices heard on the internet. No one was talking about Social Media yet — Virtual Reality was still a really big deal back then. Virtual Presence and Virtual Space were assumed to be around the corner. A smart well-regarded curator told me that because of VR, we would soon be struggling with the “split awareness of being two places at once.” I reminded him that we had overcome that problem almost a century ago. And asked him to imagine what he would think if I were to address him in person with the peculiar telephone grammar of “Hello, this is John. Are you there?” (I was too clever by half, as he never showed my work again.)

As a sculptor my mind was going in the opposite direction as those around me. I was already longingly eyeing the technology to out-put the virtual. I didn’t want to be a ghost in the machine, I wanted bring digital objects into real space as real material. I still remember being annoyed that the artist Michael Reese used “3D lithography” to make sculptures before I had a chance to. But like everyone else I didn’t have the wherewithal to see how the virtual would interface with the actual when it came to political protest, but no one else did either.

The Arab Spring was a series of mass protests that self-organized online (a bit like a digital model – liquid, fast, easy to modify), but manifest themselves physically (point by point, almost like a 3d printer, into a solid mass) as very real protests in very real spaces. It was in those open spaces –Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt; Habib Bourguiba Avenue in Tunis, Tunisia; and the Pearl Roundabout in Manama, Bahrain—flat open spaces very much like the ones I had proposed, that whole populations were able to move together as a mass and doing so were radicalized and authorities intimidated. Likewise the Occupy Wall Street protest here in New York had a digital “backend”, but owed its success to a group of hardcore protestors who hacked the American Political landscape: rather than form a large mass for a brief protest, they made a small protest last months.

V: Republic Disfigured

The Frankentecture of the National WWII Memorial (2001-04); John Powers, WWII Memorial Counter-proposal (2001-12)

Just as the choice of a semi public space turned out to be a stroke of genius because by law is to remain open too the public, the long small protest of Occupy Wall Street was an elegant work-around to the situation Naomi Wolf described after being arrested in October of 2011 “In 70s America, protest used to be very effective, but in subsequent decades municipalities have sneakily created a web of ‘overpermiticisation’ – requirements that were designed to stifle freedom of assembly and the right to petition government for redress of grievances, both of which are part of our first amendment. One of these made-up permit requirements, which are not transparent or accountable, is the megaphone restriction.”

Wolf is able to clearly identify the changes to what Italo Calvino called the Invisible City, but the physical changes, the horror vacui that shaped the material organization of our cities is either so obvious, that it doesn’t need to be spoken of, or, like a frog swimming in soup pot, the changes have been so gradual they are less visible than the Invisible.

David Childs, the architect of the Freedom Tower, admits to having misgivings about hardening the offices and residences of our elected officials against attack from elsewhere, because he is aware that this means he is also hardening the structures of our Republic against approach and reproach from within. Who in their right mind would try and visit an elected official’s office with a complaint? Unless you are a member of the vanishing small percentage of Americans who are able contribute large amounts to political campaigns (much less than 1% according to Lawrence Lessig), there would be no way to reach them through the mazes of impediments and security checkpoints that Childs helps design. And any attempt to do so would get you put on a no-fly list.

The bomb-proof base, the part of One World Trade Center that I find most offensive, is so offensive not only because it was entirely the product of the worst fear mongering impulses of the Bush years, but because it is also the worst reflection of our contemporary moment. During his talk at Cooper Union, Childs explained that because the WTC had twice been a target of terrorist attacks, security experts had insisted that the design for the building incorporate withstanding a hypothetical 18-wheeler tractor-trailer packed full of C4 explosives being driven up to the base of the tower and detonated.

I don’t dismiss the need to protect the site, I am however, totally disgusted by the politics that made it possible to drive a semi alongside the tower’s base. As Childs explained, the residents of Battery Park City fought the efforts to burry the West Side Highway alongside the WTC site. Had the highway been buried as part of the rebuilding effort any truck laden bomb blast would have been easily contained underground and no bomb-proofing would have been required. The problem is that that would have united Battery Park City with the rest of Manhattan, and that is not what the developers of Battery Park want.

Battery Park City is built over landfill removed from the deep foundations dug to support the original Twin Towers (the underappreciated “bathtub” that miraculously withstood the collapse of the Towers). The excavated rock and soil was dumped off the West Side Highway and is remains separated from the rest of downtown Manhattan by that wide busy roadway. Battery Park City has developed into a posh semi-private enclave. It is to New York what the Green Zone was to Baghdad: a foreign toehold, sectioned off and protected from the city around it. But instead of a fortified American exclave within a Middle Eastern war zone, Battery Park City is a Disney-esque planned community for those who work in New York, but want to live in Dallas.

Cut off by the highway, Battery Park has its own theaters, restaurants waterfront, and playfields (I have never seen any where near the amount of sports equipment anywhere else in NYC as on display each afternoon in BPC), all of which are so difficult for most New Yorkers to visit, that it may as well be in Dallas (it looks and feels a bit like Dallas). It is not a walled community, but it may as well be. Had the West Side Highway been buried it would have lost it’s exclusivity. Its parks and theaters would have become more like other New York spaces – crowded. Its fate, should crime rise in the city, would have been to suffer the crime wave with the rest of us.

But that didn’t happen. With the highway in place there is no threat of that sort of reversal. The cost to the rest of us is a disfigured Freedom Tower and a disfigure New York City. Battery Park city started out like a blister on Manhattan’s toe, but has grown to be a clubfoot. But the disfigurement of the World Trade Center is the same division that is disfiguring all of America. Walled communities, private security, private jets, private schools; the wealthy are abandoning our public infrastructure, and so have nothing invested in its success.

VI: A Modest Proposal for Tiananmen Square

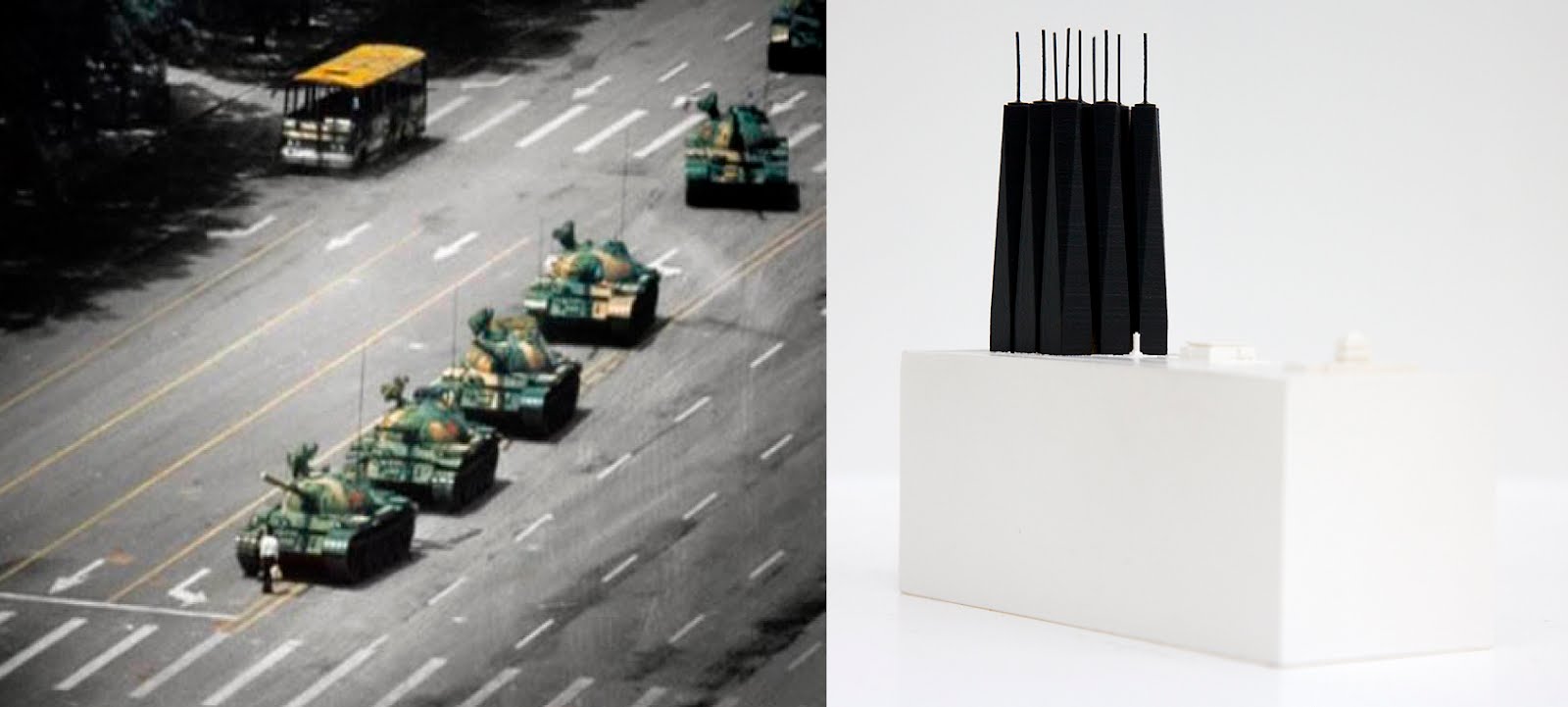

Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests (1989); John Powers, Proposal for Tiananmen Square (2012)

I propose building nine Freedom Towers on this underdeveloped site. Each tower would follow the SOM design, and have a bombproof cubic base 200’ X 200’ X 200’ of “impenetrable concrete.” The towers will then rise another 1150’ and finally, sprouting from a circular support ring “similar to the Statue of Liberty’s torch” will be tall radio towers for a total height of 1776’. These 9 towers would fill the entire 38 acre square, allowing only narrow grid of open space for traffic – a “win-win move for development.” The duel premises, that large unbroken urban spaces are fascist marching grounds in some essentialist way and that freedom can be “represented” (rather that expressed) by bombproof architecture, can be simultaneously tested by this proposal.

In 1989 Tiananmen Square was to the site of massive pro-democracy protests, thousands of Chinese citizens were arrested, and no one knows how many were killed. The image of a man standing by himself in front of a line of tanks electrified the world, but the whole truth is this that picture of a lone figure was only possible because of the tens of thousands of men and women who stood just outside the frame. That great gathering was possible only because the crowd had the room to stand together, in mass.

While Tiananmen Square has long been the site of state sponsored pageants it is now synonymous with spontaneous popular uprising. New York City has no such place. In 2004 office of mayor Mike Bloomberg (R) protected the RNC from the possibility of a massive protest when it ruled that Central Park’s Great Lawn was unsuitable for political protest because it was feared the crowds would damage the sod. Despite the fact that the sod there has repeatedly supported massive crowds for concerts, the mayor’s justification stood up in court. If New York had had a large artificially surfaced space like Tiananmen Square, the authorities would not have been able to justify, even to the friendliest court, turning down a request for a public meeting.

It would seem that a free society must protect itself from political protest by foreclosing on the possibility of mass gathering. China, as it continues to liberalize, should take a page from American urban planners. Just as American cities and universities have divided and built-in the large civic spaces that hosted political protests in the 1960s; China should avoid the embarrassment of another violent crackdown by replacing the possibility of mass dissent that Tiananmen Square presents. The 38-acre site can be easily transformed from political lightning field to a symbol of freedom surpassing the dreams of American developers. While SOM’s Freedom Tower is actually the bastard child of committee compromise, unrestrained commercial interests, and a Fortress America commitment to security against all possible enemies (read: fear-mongering scare tactics), it is clad in the heaviest veneer of symbolic program. No element, no mater how patently cowardly, is lacking in symbolic importance (afraid to actually build something 1776’ high? Add a really tall radio tower symbolizing freedom). If the Chinese are to develop into a vibrant commercial society like the U.S. they need to start avoiding the possibility of direct democratic processes of accountability now. The first step can be the creation of 24 million square feet of office space and destination shopping.