Astoria Scum River Bridge, 2010.

You define yourself as a "dude who is just trying to make things a little better." Each one of your works tries to improve the world, one funny step at a time. But they also include observations into the way in which society—and especially media and advertising—affect the way we see things. How do your works try to tamper with those viewpoints or comment on them? And can you talk a little about some key terms like subversiveness, pranks, humor, and dialogue in relation to this?

I'm interested in creating provocations that disrupt systems for good and/or fun. In particular, I'm hyper aware of the consumption narratives that shape our daily lives. Advertising literally works by telling you that you're not good enough, and all of media is shaped—directly or indirectly—around selling you stories framed by this intentionally soul-crushing lie so you'll consume more.

So a lot of what I do is prototype critical "solutions" for systems like these, exploring new answers outside of the usual channels. I've rarely seen real, important change come from inside a system; the system exists, first and foremost, to perpetuate itself. And many of the best solutions threaten the status quo of the system, so they're never realized because they will change how the system itself works.

I have the luxury of being outside those systems, so I can propose crazy, radical, preposterous, silly ideas. And not just propose them, but execute them and see what happens. Of course sometimes these interventions will be interpreted as threats, but that's how you move a conversation forward.

And, well, solutions are better when they're funny or clever or playful. Most people like jokes, in my experience.

You reflect on the workings of our society, commenting about the way the city works (including a slight obsession with the MTA), the way the art world works (in Museum Water Gun Fight and Subway Art Gallery Opening for example), and the way we use space around us. Do you expect certain results from these gestures?

Bless the MTA and their patient silence. I'm not through with them yet.

In daily life, I try to employ a stoic technique called negative visualization, which is (roughly) an attempt to eliminate all expectations. While this leads to some inefficiencies, it also creates a life full of wonder and surprise, and eliminates a lot of disappointment.

So I don't expect water gun fights or joke signs to do much of anything. I certainly don't expect them to Change The World, if that's what you mean. But I do think they can prototype ideas for using everything around us that we take for granted in inspiring, generous, novel ways.That larger system of thinking – being an active participant in your own environment—maybe that can change the world. At the very least I expect to have fun, which is maybe a radical act by itself.

The bio on your website includes the following: "His doings have been seen worldwide because they're all on the internet. Also they've been seen worldwide in galleries, but no one really goes to those…" You react to the internet in a variety of very different ways: first of all, you seem to be very committed to open source and creative commons. Secondly, you rebel against internet authorities, so to say, in projects like @free NYTimes and Kickbackstarter, and third, your own website operates both as an archive of works and a way of disseminating them further, being that some works are available to download and be returned to society (like Total Crisis Panic Button). What is your response to the internet? How do you think about the elaborate ways in which you use it?

Underlying all of this is an assumption that the internet is a public commons. Art gallery attendees are a tiny, self-selected audience, but everyone inhabits the internet like they inhabit public space (third world countries and class caveats aside). That's second nature to me, and probably anyone my age and younger. It wasn't until I read Clay Shirky's Here Comes Everyone that I started to really understand the costs of groups and communication before the web. I mean, literally, what was prohibitively expensive is now virtually free.

But the concept of "Intellectual Property" (sorry Richard Stallman) hasn't caught up. The history of ideas has only recently made room for authorship, and there are a lot of problems with this insistence that every idea has an owner. I know that nothing I made sprung from a vacuum, and I work hard to cite prior art. It seems disingenuous to try to lock up everything I've made, so I respond by doing the opposite and opening it up. I guess that fits within the larger ethos of a historical online culture.

But also, I find a project is most rewarding when it inspires someone else to recreate it or improve on it. I want to be a force for helping them succeed and push the dialogue forward, so I consider the act of giving away all my files and knowledge to be part of the project. That costs me nothing more than my hosting bill and domain name rental, so, you know, what's to lose?

Your work is experienced mainly via chance encounters, surprises, and other odd, funny moments. When there isn't always a plaque with your name by the work, what is your sense of authorship when considering the ways you present it? It seems like in a few of them, it took you weeks to claim authorship for a work that might have been around for a while and received some attention. In other cases, the work could be verging on the illegal, making your signature also a slight risk. How does authorship function for you? And do you really worry about it?

The last thing I want to do is create an authentic moment for someone and interrupt it with some sort of "Brought to you by Jason Eppink!" message. The initial (if not eventual) anonymity is vital in creating a profound sense of a world greater than our imagination, a world that magically, generously challenges itself and provides its own solutions. The specificity of authorship interrupts the mystery. "WTF?" is more important than "Who?" or "Why?." My goal is usually to create awe or wonder or puzzlement or whimsy, not to stamp my name on another part of the world. Sure I like to get pats on the back just like everyone else, but that's secondary. There's more joy to be derived from simply knowing I did something cool than from making sure the rest of the world knows it was me.

Also, I really like the feeling of giving away, of letting go, and when my livelihood doesn't depend on some sort of name recognition, I have the luxury of indulging that. If nothing else, not scrambling for attribution helps me prove to myself that whatever I'm doing is something more than a desperate plea for attention in some stage of arrested adolescence.

To address the question of legality, certainly there is some strategy to not leaving my card at the scene of a "crime," but I'm not applying paint or gluing paper to walls, and I've made the act of disassembly as simple as possible for the guy who ends up having to deal with that. The authorities would be hard pressed to accuse me of anything worse than littering.

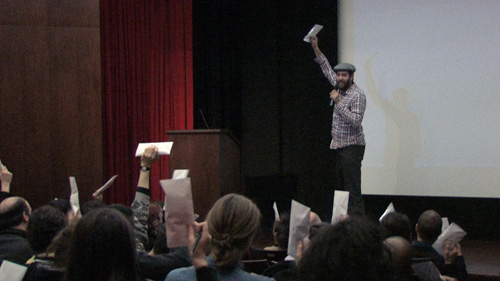

Museum Water Gun Fight, 2011. Photograph: Keith Haskel

Museum Water Gun Fight, 2011. Photograph: Keith Haskel

Age:

28

Location:

NYC

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

I made the official Twin Creeks Middle School website when I was in 8th grade. It didn't occur to me at the time to use my power for mischief. This is a big regret.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

Not to be obtuse, but I guess I basically find the tools that accomplish what I want to accomplish, and then I figure it out through trial and error?

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I finished at University of Southern California with a degree in Cinema-Television Production.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

That's a funny dichotomy. I'm not sure what falls into "traditional" media now. Video has been around for over half a century. Is it traditional yet? I use whatever media seems right for the job.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I'm entering my second year of residency at Flux Factory, an art collective in Long Island City, and I'm involved in "participatory culture" communities here in NYC.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I serve as the Assistant Curator of Digital Media at the Museum of the Moving Image. This is both wonderfully related to and entirely at odds with my extracurricular activities. At the office, I work inside an institution that must kowtow to powerful forces to sustain itself and that relies on its authoritative voice, and I end up asking for permission a lot. At home, I tell powerful forces to fuck off, try to dismantle authoritative voices, and focus on how to get away with as much as possible.

But in both spaces, I get to dive into what is novel, fun, futuristic, and changing the world, and I spend a lot of time creating interactive experiences. I'm extraordinarily lucky to be able to lead both of these lives.

Who are your key artistic influences?

Some people who initially inspired me are Rob Cockerham, Charlie Todd, the Graffiti Research Lab, Steve Lambert, and Banksy. Recently I've been digging into prankster history: provocateurs like Abbie Hoffman, Joey Skaggs, Alan Abel, all the way back to trickster mythology. Most recently: Stephen Colbert. I'm not sure how many of those people would appreciate being accused of being artists, though.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

My best projects are collaborations! Or at least they were the most fun. I work really well with Toronto-based street artist Posterchild, and I do some work with Improv Everywhere. Many of my collaborations are unauthorized, though.

Do you actively study art history?

I actively study history, some of which may include art.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

Not in those terms. I'd say my daily reading consists primarily of what Jason Kottke calls Liberal Arts 2.0.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

Yes! Giant corporations are trying to claim an extraordinary amount of power over the internet as we know it. With the SOPA and PIPA bills currently in congress, we're at a critical moment in the history of our data networks. These bills would essentially criminalize the internet! And incredibly, the debate continues over net neutrality: whether the FCC should require ISPs to treat all network traffic equally. If these decisions go the wrong way, they would stymie cultural innovation online, creating enormous costs for anyone imagining new and exciting uses for these incredible tools that we've only begun exploring.