As part of this year’s Transmediale festival in Berlin, media artist Johannes P. Osterhoff organized an online collaborative performance of search engine queries, simply titled, “Google.” For one week, Osterhof convinced myself and 36 other participants to add a unique search method to our default web browsers so that everything we “googled”—from the personal to the mundane—became instantly visible online at google-performance.org.

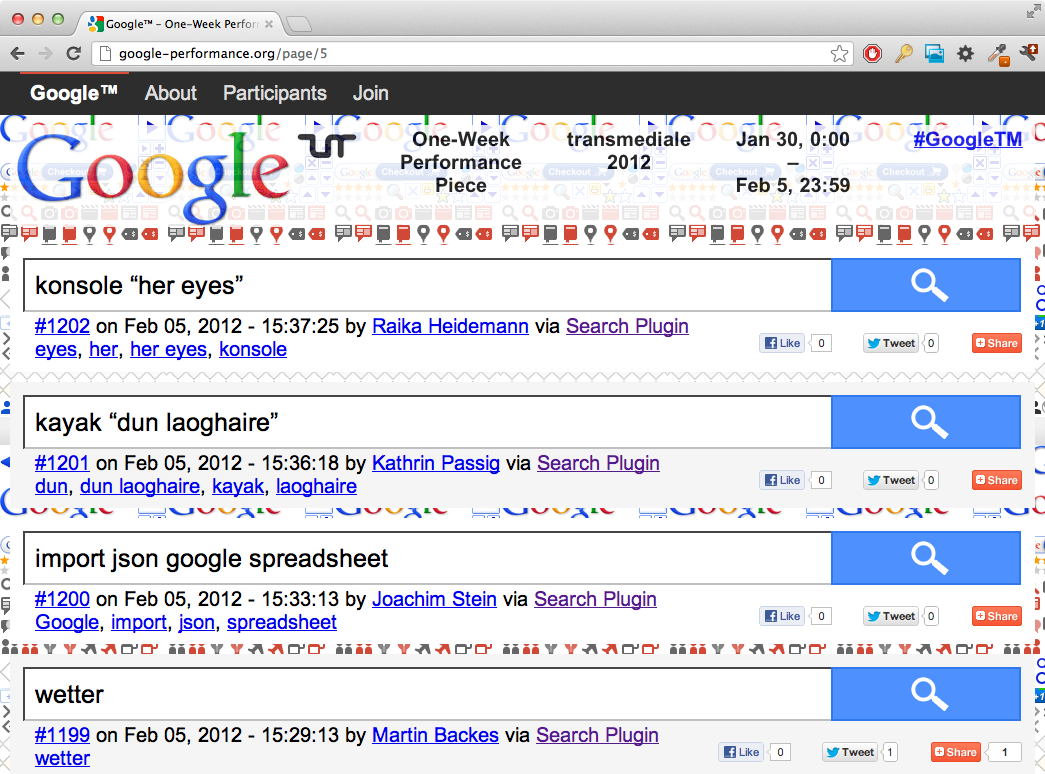

The performers, who are mostly artists or technologists or both, recorded 1,322 searches over seven days. Search queries were displayed chronologically with their sequence number, date and time, participant name, and search tool used. The text of the search and participant name were also hyperlinked, so searches can be explored by keyword or participant.

Many queries reflect content from the Transmediale conference. Others reveal users engaging in play, submitting insider messages or odd one-liners. Most searches are about business as usual, as evidenced by the high number of phrases referencing programming or technology. Reading through them, by time or participant or keyword, gives the impression of a conscious stream of thought. They are a random series of words and phrases that make irrational leaps from noun to verb to sentence, only occasionally creating a complete thought when a participant repeats parts of phrases in their quest for the intended outcome.

The queries are often poetic, like these from my own stream:

xmas

release serial ports

release serial ports arduino

chariot sidecar

pull down resistor

Others are strangely suggestive, like this snippit from Osterhof’s searches:

mspro

jennie garth

chrome french download

extrem wohlgeformet google suchanfragen mit poetischer kraft

ed2000

Sometimes they are coincidental, like these which share the common keyword, “python:”

python copy file os

Monty Python New Movie

python random coin flip

python do while

The project (see also its manifesto) made public what Facebook, Google, and any search engine, web-based tool, or social networking website already do—it harvested and re-represented users’ data in a new context in exchange for providing digital services. Google uses queries to create user demographic reports and sell targeted advertising space to marketers. Facebook does the same using content shared on their website. Instead, Osterhoff’s project, which arguably provided a cultural service, asked “how is search data different from all the other data we share?”

In her book, Undoing Gender (2004), Judith Butler says we perform our identities—that decisions we make, conscious or not, are meant to communicate who we are, and perhaps who society thinks we should be. This idea, of an outward staging of oneself, is manifest in the information age thanks to server-side software and the web2.0. Social networks take the idea to its techno-extreme by giving us unlimited options for showing “who we really are,” and “undo,” should we change our minds. However, if all our online actions are a conscious self performance of identity—the poking, tweeting, posting, liking, tagging, commenting, friending, bookmarking, subscribing, and sharing—what do we perform unconsciously?

We execute a significant number of physical actions without being conscious we are communicating. Yet our desires guide us in physical space without active intent. In virtual spaces we make decisions too. Whether aware or not, we know (or think) it affects how others perceive us, and how we perceive ourselves. Osterfhof’s, “Google,” makes explicit not only the gathering of information that we want to share, but the tracking that happens without our intending it.

Knowingly or not, we carefully choose what data is displayed on Facebook. We spend time manicuring the text and images on our profiles, or deciding to “friend” someone or not, in a conscious effort to create a digital identity that matches how we want others to perceive us. We perform our online identity every time we remove or censor embarrassing posts from our mothers, strange things high school acquaintances post, and anything else that doesn't match the image we intend to project.

While Facebook “has collected the most extensive data set ever assembled on human social behavior,” what we search for on the other hand, is rarely edited and therefore provides a more accurate sample of our uncensored desires. Unlike the identity we perform, we are unaware there is an audience for our searches, and therefore uninhibited. Like our unconscious decisions in the physical world, where our actions are a reflection of our intentions, this collection of data, this passive retrieval of our unconscious digital trail, is reassembled to form a composite of our desires that is many times more accurate than the profiles we groom for others to see.

Because of this, taking part in this performance was slightly unnerving. Knowing my searches would be broadcast caused me to consider what I submitted. The hidden tracking of a part of my life had been made visible, forcing me to consider how I represent myself, and it was an odd experience.

In January 2001, Eva and Franco Mattes ( http://0100101110101101.org ) launched Life Sharing (a word play on File Sharing), and made the contents of their computer, the private files and directories, public on their website for three years. Users could browse “texts, photos, music, videos, software, operating system, bank statements and even [their] private email.” The absurdity of this gesture is lost on us now, because as they state on their project webpage, this work was made before social networks like Facebook existed, and before data privacy was a contemporary issue.

Also worthy of mention is Osterhof’s current project, iPhone live, which captures and uploads a screenshot of whatever happens to be on his smart phone at the moment he presses the “home” button. This performance, which began on June 29, 2012 and will last one year, is an conscious gesture that, like the Life Sharing and the “Google” Transmediale performance, unconsciously exhibits evidence of the artists’ private, mediate life.

I haven’t seen much of a discussion online or elsewhere around this concept in identity politics as applied to identification of targeted ad demographics through clandestine data retrieval. That is, an “unconscious performance of identity” made possible by data we don’t censor. A truthful and raw rendition of our wants and believes for any agency interested in identifying, segmenting, and influencing our behaviors.

It is important to note that this is part of a larger trend, a move from active performances of identity, to identities assembled through unconscious passive data retrieval systems. In recent years, we’re taking the time to describe ourselves less, and allowing the systems we use to characterize us based on our actions more. Through tracking us, these systems learn about us, and fill in the blanks automatically.

Osterhof’s work not only makes us more conscious of the data trail we leave when we search, it makes us more aware that while we’re all performing, we’re also all looking. We perform the voyeur, looking at ourselves, looking at others, looking at others looking at others. When we analyze hits on our webpages, comments on our blog, or even or even when we Google ourselves to see if we’re famous yet.

We Google all day long. Its our starting point from which we clumsily sip our coffee in the morning, or gather knowledge for whatever ails us in the eve. We just type, and like magic, most of our answers can be found in the portion of the internet Google indexes. And, when we type in that little box, everything we submit is recorded, by Google, always.

Unless you have edited your preferences, you can see your cumulative searches on their website. I did. Google has recorded 45,012 of my queries since 4:19 PM on January 29, 2006. In fact, I just added 287 since the last time I looked, two days ago.

So what do I know looking through these records? I know that on 2:43 AM on April 27, 2006, I was searching for “Joshua Tree National Park,” and at 10:15 AM on April 29, 2007, I was installing PHP 5 on a Macintosh, and at 12:21 PM on February 28, 2009, I was trying to find Captain Tony’s Saloon in Key West, Florida.

Knowing this information doesn’t help me, it helps Google. By allowing us to see it, they are presenting a model of pseudo-transparency. All governments, even those under the administration of those for whom data openness is a key issue, will always maintain clandestine operations. We the people will never know what sort of black ops and measures of torture are committed in the name of freedom. Regardless of whatever “transparency” rhetoric the Obama White House or Google, Inc. uses, we will never see how our data is used. Sure, we have the option to “personalize our search results” but we won’t see the interface that examines our propensity to commit a crime, or purchase a particular item. We won’t see the tools which track, segment, and flag us and won’t ever realize how our data is already used to influence us.

It’s safe to assume the majority of Transmediale’s audience already knows much about the tracking that goes on. They understand the cost of free web services is individual privacy and that the consumer / customer model has changed. We are not Google’s customers, instead they collect data we consume and sell representations of it and targeted ad space to their customers: the advertising industry, corporations, and political parties. The scale of this activity is what may not be clear without research. That is, 96% of Google’s revenue, over $36 billion dollars, in 2011 came from advertising, and that it was possible because they track everyone that uses their services.

The general audience that might encounter Osterhof’s artwork is more diverse, but probably still clued-in even if privacy is not a top concern. As poetic as his gesture is, and primal as my response was as a participant, the challenge for a work like this is reaching and communicating to an audience, and engaging them to think, learn, or question, and motivate them to care.

How will the work contain the attention of someone who doesn’t already agree with Mr. Osterhof, and inspire them to regard the issue enough to do something about it: To not allow themselves to be tracked; To use anti-tracking software when they browse online, or a browser that supports Do Not Track; To make an artwork or write software that raises or frames these issues for others to consider: Or just to be aware, and make decisions which change the culture of the Web2.0, and influence it, slowly, but surely, to respect privacy. And to know that, in this techno-utopian-neoliberal wet dream that is dripping with app stores, computer waste, and rampant consumerism of binary data under the blanket of the good-natured term, “free market economy,” that “freedom” stated another way, means “do not track me without my consent.”