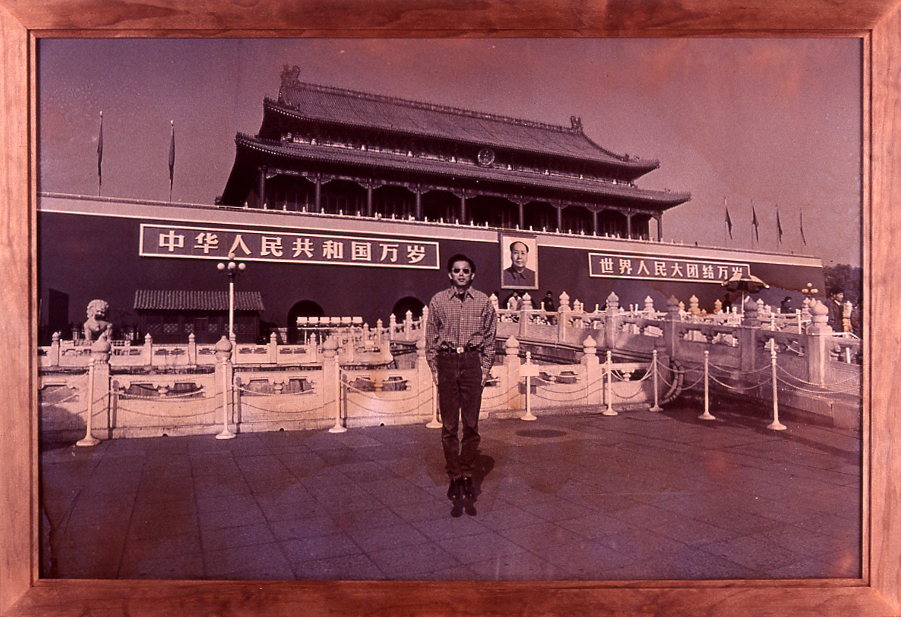

Yao Jui-chung, Recover Main-Land China : Action (1996)

As an outsider the Taipei art scene can be difficult to access. The dearth of information in English and the lack of an international profile – compared to other countries in Asia – can make it appear a mysterious black hole. And perhaps that’s precisely the appeal. Amidst the increasing standardization of the global art world, somehow Taiwan missed the brief. As usual it was left out of the loop.

Not officially recognised as a country – after it was abandoned by its allies and booted out of the UN in 1971, as the body instead came to recognise the Communist People’s Republic of China – Taiwanese life seems characterised by diplomatic and cultural isolation. I remember living in Taiwan during the SARS epidemic of 2003 when, as Taiwan is blocked from attaining membership of the World Health Organization (WHO), the island was refused medical expertise and information. Eventually the U.N. body sent over an expert, only he became infected with the disease and had to leave. The front page of the newspaper showed a photograph of him walking back to the airplane, dressed in strange protective clothing, looking like a displaced astronaut. Once again Taiwan was left to its own devices.

I’ve heard it said that the uncertainty of Taiwan’s future leads to a kind of nihilism. I first encountered this dark vision when I watched Tsai Ming-liang’s feature film The Hole (1998) shortly before I moved to Taiwan in 2000. The film is set in Taipei in the final days of 1999. A strange virus has spread throughout the city causing its infected persons to writhe on the ground in cockroach-like movements. An evacuation order is ignored by the residents of an apartment building who decide to wait out the storm. One of the residents answers a knock at his door to encounter a plumber who has come to check the pipes. The resident leaves to open his small grocery store and upon returning home discovers that the plumber has drilled a hole through his concrete floor. The man begins voyeuristically using the hole to observe his woman neighbour who lives below, but eventually the hole becomes the only means of human interaction the two neighbours have. The film is bleak and claustrophobic, mostly set at night in the city where it seems to never stop raining. But the darkness is broken by occasional jolts into wild and colourful musical scenes, hopelessly nostalgic and desperate in their overexuberance.

Chen Chieh-jen, The Route, (2006)

Chen Chieh-jen, The Route, (2006)

Taiwan’s best-known artist Chen Chieh-jen draws on the island’s isolation in his 2006 video installation The Route. The work, commissioned for the Liverpool Biennial, restages or re-imagines an historical event, the global dockworkers protest of the 1990s. The protest began after 500 Liverpool dockworkers were fired in 1995 for refusing to cross a picket line. Later, when the scab-loaded ship Neptune Jade left England for Oakland in the US, word spread of the workers’ struggle. The ship was met in Oakland by a picket line of labor activists and community organizers who, in solidarity with the Liverpool dockworkers, defied a court order in refusing to allow the unloading of the ship. After three-and-a-half days the ship headed onto Vancouver where it met the same scenario and then onto Yokohama, and then Kobe, Japan, where again dockworkers refused to unload the ship. Eventually the ship sailed to Kaosiung, Taiwan where Taiwanese dockworkers were unaware of the global action. There the ship was sold and its cargo discharged. For his installation Chen staged and filmed a belated protest in Kaosiung, interspersing these scenes with archival documentary footage of the global protest, echoing the Liverpool dockworker’s phrase, “The world is our picket line.”

But perhaps I am making too much of this isolation or employing nostalgia myself for a time I never experienced. The 1990s in Taiwan is referred to as a period of “Taiwanization”. Following the lifting of martial law in 1987 and the rise to power, in 1988, of the first Taiwan-born president Lee Tung Hui, there was an explosion of artistic activity as artists explored the island’s long suppressed history, languages and indigenous cultures in a concerted effort to develop a culture and identity that was uniquely its own. The island became a democracy and the economy boomed in a time when anything seemed possible. There was a crescendo of optimism in 2000 when the independence-minded Chen Sui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party was elected president, despite threats from Mainland China and military exercises conducted just of the island’s shores. But such optimism now seems a distant memory as Chen Sui-bian sits in prison, serving a life sentence for money laundering, bribery and embezzlement of government funds.

The tide of globalisation has swept over Taiwan as its factories have relocated to mainland China, in search of cheaper labor, and even its artists are moving to the mainland in increasing numbers, looking for opportunities. A friend of mine, a businessman, who is one of the most patriotic Taiwanese I know, recently told me that, after resisting the tide for many years, he has resigned himself to the situation. He is moving to the mainland. In contemporary Taiwan consumerism runs rife. “Taiwan,” Chen Chieh-jen told Studio Banana TV, “has become ‘a fast-forgetting’ society that has abandoned its right to self-narration…” A new generation of Taiwanese artists seems detached from the island’s historical situation, which seemed so urgent only a decade ago.

“Most younger artists are no longer interested in grand narratives,” Yao Jui-chung, one of the island’s leading artists, told me when I interviewed him for Afterall Online last year, “nor do they directly challenge traditional or exalted values, but rather use gentler, more personal strategies, avoid problems (both intentionally and unintentionally) and escape into their own communities... While most of this work is clever, ethereal and speaks of personal experience, this is not enough. If they cannot construct their pastiche of fragments on a fully elaborated genealogy of knowledge, then the superficiality of their project is likely to cause it to collapse.”

Yao is among many Taiwanese who are determined to counter the amnesiac state created by rapid commercialization. Any visitor to Taiwan interested in its history and art scene would do well to meet Yao. We first met at Adam Art Gallery in Wellington in 2006 when he came over for the exhibition Islanded. Upon returning to Taiwan, with my brother Mark, in early 2009, Yao took us on a whirlwind tour of Taipei, introducing us to artists, galleries, curators and daring us to try local delicacies, like “The Four Gods Soup”, containing pig’s bladder, urinal and sperm tract, offering us betel nuts and taking us to a traditional puppet theater where the performances are intended for the gods. Yao’s patriotism for Taiwan and political outspokenness can be problematic for his art career. His work has, at times, been banned from being exhibited in the mainland. Yao’s photographic action series, Recovering Mainland China (1997), parodies Taiwan’s former official policy of one day retaking the mainland. As a member of the last generation to still be taught the policy in school, Yao photographed himself standing, feet floating above the ground, in front of various Chinese historical sites. Dressed in military uniform, leftover from his compulsory military service, Yao is there as a one-man army ready to carry out the official government policy. I remember Yao telling me about some trouble he once had with Chinese customs officials at the airport due to the work as he struggled to explain that this was art and that he wasn’t really intending to retake the mainland.

Yao is currently the interim Director of the Taipei Contemporary Art Center. The center, which opened in 2010, is at the heart of a grassroots movement by the art community to reclaim its self-determinism. Situated in the Ximen district — a strange mix of rundown historical buildings, teen pop culture and veteran soldiers and the seedy underworld they inhabit — the center, despite its official-sounding name, is a non-profit organization formed by a group of artists, scholars, curators and cultural workers endeavouring to create an independent initiative whose operations are not affected by government policy or business interests. Prominent artists, including Chen Cheih-jen, donated artworks to help raise money for its establishment. The center now appears set to move to a new location at Zhong Shan ArtsPark where it will have an office and access to facilities in the park. The center will be participating in the Shanghai Biennial in October. Yao is also a founding member of a group of artists who run VT Artsalon, an independent gallery and bar which functions as an informal meeting point for artists.

Isa Ho is another artist who has been a strong profile the past few years. Ho’s photographic collages draw on a rapid flux of different characters, played by the artist herself, exploring the contradictions and demands created by rapid modernisation and its uneasy relationship with a still dominant traditional culture. “For women,” Ho says, “we are taught to follow the teachings of the “three obediences and the four virtues,” and this includes to be docile. Quite simply put, typical families in Taiwan think that girls should talk less and not have too many thoughts and suggestions. However, as the girls enter the job field, they can’t afford not to talk or have any thoughts. They must play the game to compete. On the other hand, traditional education preaches that men should take on the responsibility of supporting their families. However, in the real world, due to intense economic pressures, men have to accept the fact that their significant others are also bringing home the bacon; thereby, the male status at home is also shifting”.

Isa Ho, This New Year's Eve we signed the peace treaty (2008)

One of things I’ve noticed about mainstream culture in Taiwan is an almost universal obsession with fairytales. In her photographic series I Got Super Strong Courage – I Am Snow White (2005-2010), Ho plays Snow White, hyper naive and innocent, set in a range of complicated environments, surrounded by even more complicated characters, also played by Ho, often contradictory female roles brought on by contemporary Taiwanese conditions. “The [obsession with] so-called fairy tales is because they bring us a better vision and always have a happy ending,” Ho says. “Everyone in childhood was told that the prince and the princess lived happily ever after, which means the good outcome is also a symbol of marriage."

Technology and political developments in Taiwan have presented their opportunities. With the high speed railway one can now travel from Taipei to Taichung City in one hour, and Kaosiung in two hours. There are now direct flights to the mainland, whereas previously, due to political reasons, one would have to first fly to Hong Kong and apply there for a visa. There are still restrictions on mainland Chinese visiting Taiwan. It is not always simple for artists to make the trip over.

Recently the magazine I edit White Fungus flew over the Beijing noise artist, writer and record label boss Yan Jun to perform in an event at Taipei Contemporary Art Center alongside the Taipei artists Wang Fujui, Dino and Wang Chung-kun. Yan has been familiar with Taiwanese experimental music for a long time and it was interesting to hear his thoughts after returning to the island for the first time in many years. “My impression is that Taiwanese musicians have clearer directions and figures than Chinese ones. I feel there is more of a working atmosphere. In China many musicians are constantly trying and struggle in the crazy reality. And there is no community. You know how difficult it is to meet people in Beijing – now I’m waiting for someone who is already two hours late – and how difficult it is to do anything in a smaller city in China. Anyway, I like the quality of Taiwanese musicians and the energy of Chinese musicians.”

Jeph Lo has written extensively on the history of experimental music and sound art in Taiwan. In his article “The Taiwanese Sound Liberation Movement” he ties the emergence of these forms directly to the political climate of the times. “Soon after martial law was lifted, the government gradually removed the many existing prohibitions, and a wave of political and social movements swelled up, including the environmental, gender / sexuality, labor, and Taiwan independence movements. All positions, no matter how controversial, could now be voiced publicly… The first wave of the Taiwanese sound liberation movement was born against this backdrop.”

Hsia Yu, Pink Noise (2007)

One of the artists Yan Jun has introduced me to is the Taipei poet and publisher Hsia Yu. Hsia, inspired by the underground noise community, seeks to create in her poetry a verbal equivalent that she describes as “lettristic noise”. Hsia’s 2007 book Pink Noise was an underground hit, selling 4000 copies and reaching number 4 on the bestseller list for the Eslite Bookstore chain. The book is a series of 33 poems published in Chinese and English. Printed on transparent leaves, the poems, in black and pink, ink bleed into one another in a staticky mesh. The artist composed the poems in English using lines found by clicking hyper links on spam emails, mixing in lines from literary classics by Pushkin, Poe and Shakespeare, among others. Once composed Hsia fed the poems through the automated translator “Sherlock” and then continued working with the awkwardly transferred text, feeding the Chinese back through the machine to obtain the English text.

“It ‘translates’ word-for-word,”Hsia said in an interview with Full Tilt “closely following the letter of the text, and yet the translated version provides no secure meaning. It makes no commitment; it doesn’t flow: words keep coming but it doesn’t move forward. Nor does it take you anywhere; it persists in place even if it eventually crumbles. Sentence by sentence it crumbles and then suddenly it has arrived somewhere… You know, I’ve never really cared that much for computers or the Net. No consensual hallucination induced by virtual reality can hold a candle to the most rickety sentence precariously contrived. But now I feel a new romance coming on with this automated translation software, my machine poet. And what really turns me on is that, like any lethal lover, it announces from the beginning that it is not to be trusted…”

Wang Fujui is one of the pioneers of experimental music and digital art in Taiwan. In 1993 Fujui founded Noise, the first experimental music magazine and record label in Taiwan. In 2000 he joined Etat, an independent organization, founded in 1995 by the avant-garde artist Wen-Hao Huang, dedicated to media and digital art. Wang curated Bias in 2003 and 2005, the first exhibition of sound art in Taiwan, organized by Etat. In his own work he makes sensuously-charged installations combining light and sound. Yan Jun describes Wang’s recent performance in Taipei as “so beautiful and elegantly wild”. Since 2006 Etat has directed the Digital Art Center. Wang has curated both the Taipei Digital Art Festival and the interdisciplinary TranSonic festival.

Since 2007 Lacking Sound Festival, an organization founded by four artists, Chung–Han Yao, Chung-Kun Wang, Ting-Hao Yeh and Shin-Yuan Tsai has held monthly events at Nanjing Gallery. Kandala Music organizes a range of experimental and improv concerts. There is a growing amount of institutional support for digital art in Taiwan, with the establishment of the Digital Art Center in 2006 and a plethora of new media festivals and exhibitions. However, both Yan Jun and Jeph Lo are ambivalent about the development and institutionalization of sound art in Taiwan. Speaking of the mid-2000s in Taiwan Yan says, “That was the time of ‘noise’ turning into ‘sound art’, synchronised with the process of formalising a capitalist democratic society. Now everything is named. People know what they are doing and where they are.”

Wang Fujui performing at the White Fungus Issue 12 Release Event, December 3, 2011. Photo: Feng Hsin

I’ve always found Taiwan itself to be its greatest artwork. There’s an unpredictability to life on the island which leads to constant surprises. But while I’ve felt drawn to the island’s dystopian elements, I’ve also enjoyed the traditional currents which somehow continue on despite all the upheavals. Living amidst the urban chaos of Taipei it can be easy to forget that the island was once named Formosa (“beautiful island”) by the Dutch, but there are still incredibly beautiful stretches of nature to encounter on the outskirts of urban sprawl, even if a nuclear power plant sits on Kenting, the island’s most beautiful beach. French sound artist Yannick Dauby has been based in Taipei since 2007 after first coming to the island in 2004 to do a residency at Taipei Artist Village. Now lecturing in sound art at Taipei National University, Dauby has done a number of collaborative projects in rural Taiwan, working in Aboriginal villages and learning about the island’s ecology. Currently is he doing a project recording the sounds of Taiwan’s frogs. “Taiwanese people often say that Europe is more suitable for people interested in culture,” Dauby says. “I often reply that culture exists in specific places in Europe such as concert halls or museums, but in Taiwan it still exists in the countryside, nearby a temple or in a tea garden.”

Taipei experimental film festival Urban Nomad, started by expat journalists David Frazier and Sean Scanlan in 2002 is one of the most successful examples of an art project started by foreigners in Taiwan. The festival, which now travels from Taipei to Hsinchu and Taichung and is hoping to reach an audience of more than 10,000 people in 2012, began in warehouses and alternative spaces throughout Taipei using VHS tapes and a few computer files and DVDs. “The only reason that year succeeded,” Frazier says, “was because Saturday night turned into a party and we made a bunch of money selling beer. Since then, I guess you could say we’ve been coming up from the underground, but, to tell the truth, we’re still a lot more comfortable there.” Frazier and Scanlan’s festival has succeeded in independently funding itself which has kept it out of local art politics. Despite its growth the festival still creates a social and community experience of film, distinct from the “black box” impersonal movie environment. “Now the festival involves a lot more spreadsheets, invoices, etc,” Frazier says, “but venue and atmosphere are super important. We don’t want people to just show up, pay for entertainment, download it to their brains and leave.”