“From Nethack to play-by-post forums on the WWW,” an Ars Technica blogger wrote in 2009, “the first thing that computer geeks do upon inventing a new medium is play Dungeons and Dragons with it.” With this half-joking riposte to conventional wisdom that new communications media are appropriated first by pornographers, the blogger introduced a roundup of instructions for adding dice rollers to Google Wave to make it a platform for turn-based role-playing games. Of course, links between computing and RPGs predate networked technology. Some of the earliest computer games were made by programmers who played D&D; and saw the connection between dice and digits. Another parallel might be drawn between the do-it-yourself culture around computing in the 1970s and the amateur storytelling demanded by RPGs. Even while computer use leaves less to the imagination today than it did thirty-five years ago, it still shares more characteristics with RPGs than older forms of entertainment do. The creator(s) of a novel, movie, or drama have combined details into a whole by the time it reaches an audience; those media come with spatial and temporal guidelines for consumption. But just as network connections are constant and pervasive, RPGs are open-ended, played with regularity and long-term commitment. Gaming (like, say, tweeting) doesn’t have the same distance between medium and audience as reading or film-going – there is a constant awareness of the self’s participation in a bigger system, and a feeling of contribution to it. RPGs, like internet use, move at the speed of life.

I think this affinity is what has prompted many artists to include allusions to RPGs in their works. Whether they adapt the forking structures or the surface details of fantasy and science fiction, whether those references are direct or oblique, references to the culture around RPGs can be shorthand for reality’s mediation by immaterial systems. Some examples: Brody Condon’s remakes of medieval paintings with game graphics, Eddo Stern’s animation of a gaming-forum flame war, Deb Sokolow’s choose-your-own-adventure drawings, the arcane protests of the Center for Tactical Magic, Sterling Crispin’s scrying devices, and the occult forms behind altar .gifs on dump.fm. These artists a have relationship to fantasy that’s distinctly different from ones who make monster portraits and fantastic battle scenes – a genre that’s also become more visible in contemporary art the last few years. (That trend, I’d say, comes because popular and critical approval for Peter Saul and Tim Burton has emboldened a younger generation of “outsider artists” who grew up with RPGs.) Indie fantasy art, like the illustrations in novels and gaming manuals, that inspire it, is about virtuosic draftsmanship and imagination. It showcases fine renderings of dragon scales and weaponry. The examples I listed above have rough edges where processes of imagination and play visibly collide with other frames of reference. Often, they achieve this by bringing technology to the foreground.

The difference between fantasy art and the kind of "art about fantasy" I’m discussing here was apparent at “Doomslangers,” an exhibition hosted by Allegra la Viola Gallery last fall. Nearly all the works presented were paintings and drawings based on the artists’ personal mythologies. An exception was Chris Coy’s Invisibility Cloak Study (rough). In the video, Coy “vanishes” beneath a chroma-keyed white sheet – a trick that leaves him partially visible. He’s standing in the middle of the road in a low-traffic, residential area. The obvious intervention of software and the suburban setting both ground the magic item in everyday life. Coy addresses similar themes in The BAMF! Studies, a YouTube playlist. Each video shows its maker jumping across a short distance in a vaporous cloud, simulating the mutant power of the X-Men character Nightcrawler in their homes. In comics and movies, Nightcrawler’s teleportation is one of many details contributing to a plot, supported by setting and character. But in these videos the effect is isolated; if it’s part of any story, it’s one of teenage boredom or angst and the use of imagination to overcome it.

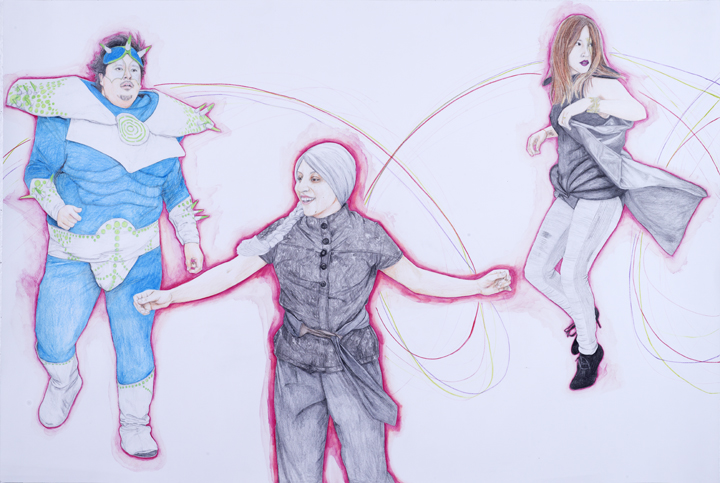

Coy pointed out in a conversation that almost all of the BAMFing videos are made in kitchens and living rooms. He suggested that their creators are asserting mastery of the home’s common areas – a contrast to the basement, the classic site of the teenage D&D; session, or to the private gaming lairs collected by Guthrie Lonergan in Domain. His observation further emphasizes fantasy’s close involvement in everyday space. Lifted from Nightcrawler, BAMFing enters someone’s personal history. Similarly, elements of RPG, detached from a hermetic narrative, attach themselves to personal lives. Johan Huizinga’s classic five-part definition of games in his 1938 book Homo Ludens says that play takes place outside of everyday life. But RPGs stretch that definition. Desiree Holman’s video Heterotopias, based on her research into LARPing, visualizes the psychological process of a gamer embodying a character. Her actors first appear seated at their computers, then as animated graphics, then as dancers on a stage. Here, as in her other videos, Holman cast non-professional actors and dancers and makes extensive use of green screens. The presence of “normal” people and the emphasis of process over polish effectively liken the experience of fantasy role-playing to the everyday performance of persona. A LARPer, after all, isn’t trained in the Stanislavksi method; he doesn’t surrender his personalities to a character’s psyche, to become the character in an autonomous reality created beyond the fourth wall of the stage or screen. In RPGs the medium is approached in meta-game terms; a sense of self is preserved even as a player directs the actions of his characters within the game system. Have you seen Darkon? The nice guys in the world are the nice guys in the game, and nice guys always lose.

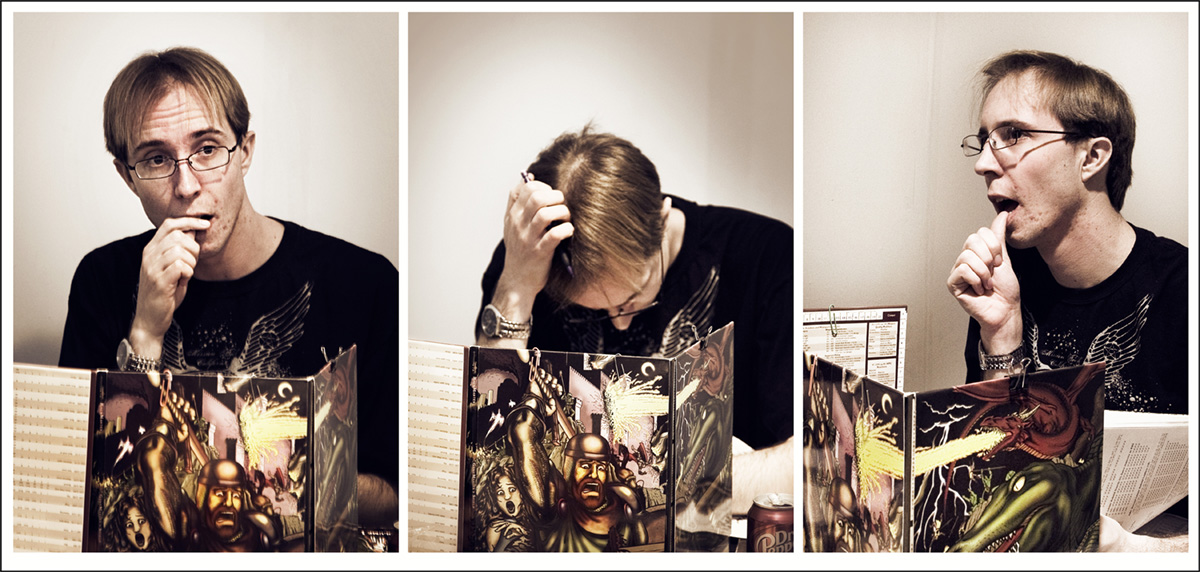

Brody Condon also focused on the gamer’s engagement with rules and expectations of character behavior in his project Lawful Evil, a staged game of D&D; at the Art LA Fair in 2007. Since its first edition, D&D; has prompted players to choose one of nine alignments when creating characters, a kind of moral code that determines certain boundaries of what the character is willing to do. Neutral good and chaotic good are the most common choices, the vigilante alignments that mean a character is willing to do almost anything in pursuit of some righteous ultimate goal. A lawful evil character “cares about tradition, loyalty, and order, but not about freedom, dignity, or life,” according to the third edition of the D&D; player’s handbook. “He condemns others not according to their actions but according to race, religion, homeland, or social rank.” That sounds familiar enough, but it’s not a viewpoint that many people would willingly associate with or deliberately choose to perform. Lawful Evil enhanced meta-game thinking to magnify the relationship between medium and gamer.

Condon acknowledged RPGs as the fountainhead of his work in his 2008 catalogue Known Planes of Existence, with a title and cover illustration borrowed from the map of earth, heaven, and hell in the first D&D; manual. While a number of his projects involve RPGs – from online multiplayer platforms to weekend-long LARPing events – others have taken on drug use and self-help workshops. Condon’s work situates RPGs within broader explorations of the mind-body problem, which for many artists figures as a double for issues of artistic representation raised by the internet. “[I]t is assumed that the work of art,” Artie Vierkant wrote in The Image Object Post Internet, “lies equally in the version of the object one would encounter at a gallery or museum, the images and other representations disseminated through the Internet and print publications, bootleg images of the object or its representations, and variations on any of these as edited and recontextualized by any other author.” The RPG resonates with this condition as a thoroughly cross-media phenomenon, one that exists between rulebooks and games; its codes travel among tabletop, computer, and simulated battlefield. But more importantly, it is a medium that prompts a direct and open engagement with imagination. Artworks that use RPG references to locate fantasy within reality tacitly refute the rhetoric of “virtual reality,” which attributes less-authentic status of events that occur online. Such works are presented not as a gateway to an alternate universe, but another piece of one big reality.