The concept of networked art, or art which relies on exchange and collaboration across great geographical distances, has had a rich history prior to the Internet's first rumblings (and is now, fittingly enough, being archived, reappraised, and 'blogged' all over that same Internet.) Unlike the "one to many" presentational modes of the museum, shop, or gallery, networked art pieces were comparatively intimate "one to one" experiences, absorbed by one recipient at a time. Whether we call the collected efforts of this culture "mail art," "correspondence art," or simply "networking," its history is unlike other 'art historical' narratives, insofar as few people feel qualified to act as a spokesperson for the admittedly varied intentions of other networked artists: there is an almost universal reluctance to promote oneself as the "head" of anything in this culture. Especially on the European continent, where the most radical art collectives (e.g. Surrealism) have splintered into warring factions while under the mismanagement of paranoid leaders, no one is particularly eager to waste their otherwise productive time on internecine squabbling about whom deserves what title. So, in these situations, those who are just the most enthusiastic about their work, and its place in a larger creative milieu, end up becoming "ambassadors" by default.

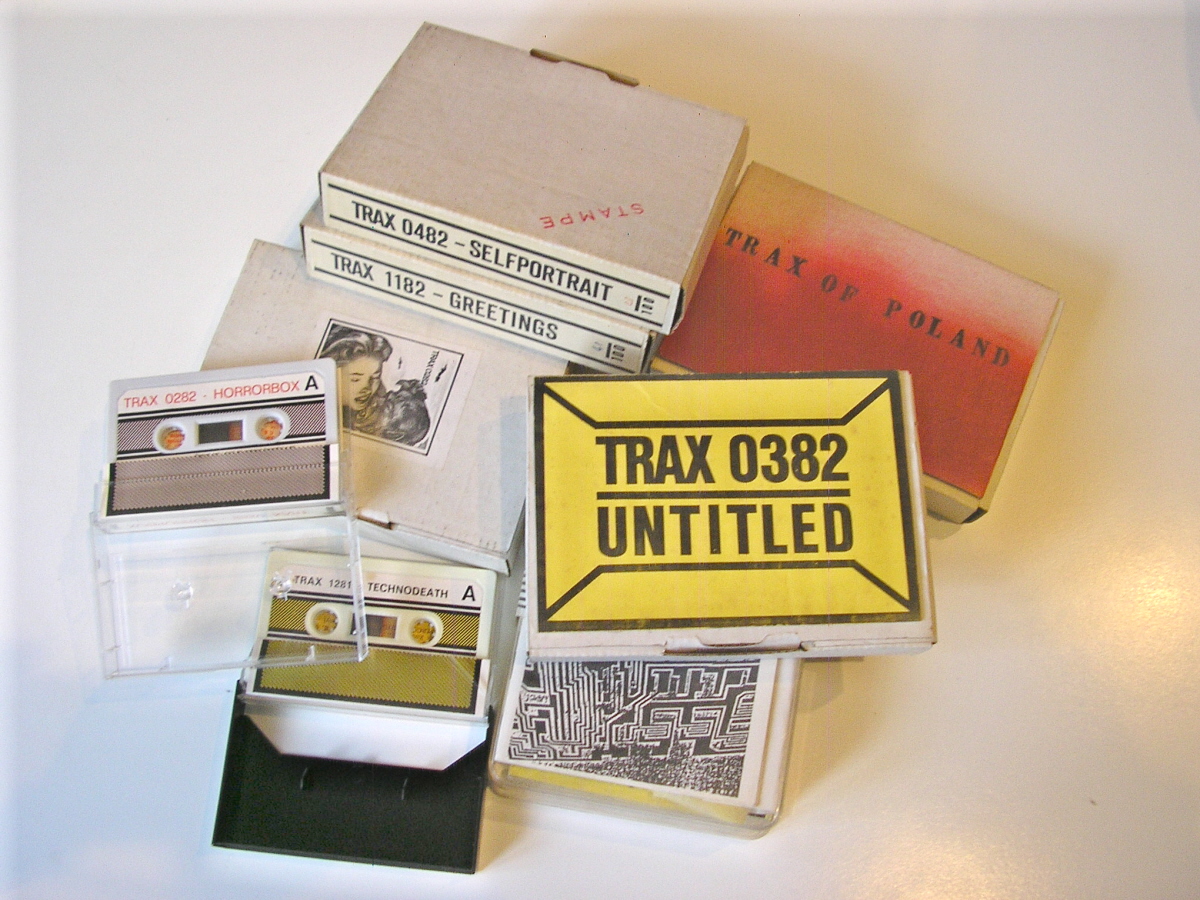

One such ambassador, Vittore Baroni, is an individual who makes introductory biographical surveys like this one such a daunting task: his work spans every conceivable medium from rubber stamps and "artistamps" [mock-'official' postage stamps] and stickers to novel fashion items, and his tastes run the gamut from sublime atmospheric music to graphics exhibiting an exaggerated 'comic book' sense of humor and horror. Other than a general disregard for the taxonomy of art genres, the defining characteristic of Baroni's artwork is the nurturing of paradox and contradiction (he tells me that "[the term] 'paradoxical' is for me a great compliment, and a very positive adjective.") However, I may be getting ahead of myself here, since Baroni disavows the word "artist" entirely. In an early manifesto for his TRAX 'networking project,' co-founded with Piermario Ciani and Massimo Giacon, Baroni demurs "we are not artists, because art is a word that means everything and nothing," and proceeds to apply this to more clearly defined creative categories: "we are not musicians, but we create sounds. We are not actors, but every once in a while we get on a stage. We are not writers or publishing houses, but we can print our own writings." So what exactly is Baroni - and who are "we"?

In career-oriented, technocratic society, the only available classification for a person who makes these claims would be "amateur." While this may be true in the sense of not making remuneration the main goal of one's work, it is unfair to use this in a totally pejorative sense. "Amateur" has too often connoted someone who has no idea what they're doing, and someone who will give up their petty dalliances on a moment's notice once a more colorful distraction comes along. Sure, countless people of an artistic temperament are assuredly amateurs, but few who make the effort to participate in this practice are ever this half-hearted about their creations. Rather, their amateurism cleaves closer to the original Latin definition of the word, stemming from amare [to love]: prior to the modern distinction between the professional public artist and the self-amused dilettante (which in itself would mean, in Latin, someone who is "delighted by" something), there was an understanding that creative works carried out for the furtherance of pleasure - as opposed to a career - were not ignoble, nor did they automatically connote a sense of disrespect towards all that had gone before.

Furthermore, the "amateur" attitude was not one of intentional selfishness and seclusion, since it was, by its very definition, the propagation of love and enthusiasm. Along with its obverse, the scorned amateur, the "capital-A artist" as a social type is also a fairly recent arrival in human history. Baroni explains that, despite all its reliance on modern techniques like xerography and audio collage, the motives of networked art (which Baroni insists on calling a "medium" rather than a "movement") hearken back to a pre-modern age of production:

Networking art is, in a way, a return to the anonymous collective builders of cathedrals - only this time there is no munificent client, as it is all independent and self-financed, and therefore much more obscure and esoteric. Networkers resemble mad scientists locked up in their laboratories, trying to come up with an alchemical formula capable of saving the human race (or at least to make someone smile). Their utopian quest passes through the rediscovery of the lost spontaneity and rituality of the creative act. Real cultural gain is the fruit of a hard and sometimes painful but highly rewarding personal search, not of passive consumption.

For this final reason that Baroni mentions, the amateur as "lover of life" deserves support more than ever: as certain of the online social networks turn into "promotional networks," the whole of communication taking place can be summed up in simple imperative phrases (buy this, rate this, listen to this, etc.), while impersonal "thanks for the add!" messages and implausibly huge "friend hoards" take precedence over truly reciprocal communications. As MySpace becomes more of a communicative "one way street," populated by bands and entertainers whose every status update takes the form of a product plug (or a "viral" titillation that redirects users to the product plug), it's unsurprising that its downward slide in the Alexa rankings continues. As facile as Facebook can be, and as revealing of hypermodern humans' terminal lack of focus, it has succeeded in portraying itself as the more "participatory" of the two social hubs. Its own imposing presence within the Alexa top 3 hints that the online population is increasingly electing the most banal of "participatory" activities over the most grandiose "one-way" communications. If any of this speculation is true, we should be encouraged, because it points towards a model of globalized communication in which genuine cultural plurality can win out over the monoculture that disguises itself, with cosmetic devices like custom profile page designs, as that very plurality. It would also mean that online social networks, despite having a "presentness" and lack of "emergence time" missing from the networked art from the 1970s-1990s, can become a legitimate successor to that art form (but not, it should be added, a "replacement" for it.)

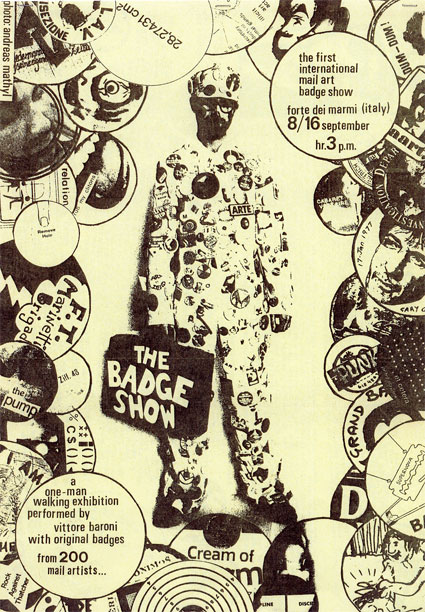

A common misconception of pre-Internet networked art is that it had a strictly hermetic character, or it was a kind of purely "telescopic creativity" that, like the Internet, brought the far away close at hand while inverting this formula for one's immediate surroundings. Some have admitted as much: the "mini-FM" broadcaster Tetsuo Kogawa recalls that "Japanese youth culture of the '80s had a kind of otaku [literally 'one's home'] culture of distance," by which anxiety over public recognition could be nullified. However, since his own initial efforts in the late '70s, Baroni has always attempted to dispel this notion, either by arranging local "networkers' congresses" or engaging with the local public in an unorthodox way. For the latter, Baroni's one-man "Badge Show" from 1981 is a fine illustration: this exhibit consisted solely of Baroni walking around his hometown of Forte dei Marmi with white overalls encrusted in badges, themselves designed by participants in the Mail Art network of the time. While the exhibition was explicitly intended as a showcase for the works of 200 different artists, it also furthered the individual intentions of Baroni himself: "every day at 3 p.m., I covered the short distance from my house to the Forte dei Marmi Municipal Art Gallery, as an ironic statement against the gloomy and provincial cultural policy of my town […] I do not like the usual gallery show arranged for the usual small crew of art freaks; I prefer to work for a non-art audience, so I performed my 'live show' for the fun of smiling passer-by."

Another means of circumventing traditional artistic venues was to simply relinquish personal control of the artwork entirely, and see what others might do with an idea placed in the public domain: as the founder of the audio project Lt. Murnau, Baroni made indecipherable cut-ups of Beatles records and released them on a VEC Audio Exchange cassette entitled Meet Lt. Murnau, while concealing his identity behind masks that bore silent film director F.W. Murnau's likeness. The mask, reproduced by Baroni in a "cut-out" version, made for a situation in which anyone could assume the identity of Lt. Murnau and make their own similar (or not so similar) audio works. Given the already established "horror film" theme of the group, Baroni collaborator Piermario Ciani suggested that this act of creating "plunderphonic" music (well before John Oswald brought this style into wider circulation) was a way of "vampirizing" sounds. As notable as any of this, though, was Lt. Murnau's status as a bridge between networked visual art and the networked audio art of the 1980s, which would take on the admittedly bland and unassuming name of "cassette culture."

The contemporaneous Industrial music culture took its cues from the Fluxus rejection of art and life as mutually exclusive categories: so, it was not averse to extending its reach with collage works, cadavres exquis, xerography and other methods emphasizing portability, ease of distribution and an unfinished quality that encouraged further input from an otherwise passive receiver / listener. As such, Industrial operatives like Merzbow, Déficit Des Années Antérieures and Maurizio Bianchi quickly came into Baroni's orbit during the 1980s. Others, like Cabaret Voltaire, contributed to the Janus Head release of Lt. Murnau (done in collaboration with Jacques Juin, of the French / German mail art project Llys Dana): this was a 7" EP with a similar sized, 50 page booklet, consisting of collages sent in from underground rock groups and mail artists from England, Italy, France, America and elsewhere. It was edited in a similar style as a mail-art magazine, while further Lt. Murnau products steadily blurred the line between 'stand-alone' music group and networked multi-media project: Maxi-Single (a cassette magazine), Xeroxzine (a fanzine), and Tabu (a disc with objects) all bore the Lt. Murnau imprimatur.

The aforementioned Ciani was another major component in the collaborative project, TRAX (1981-1987), that would come to encapsulate all of Baroni's different methods and proclivities. Ciani was also interested in taking the question of public recognition and irreverently mining it for creative materials: his completely imaginary music project, The Mind Invaders, existed in images but never performed or recorded (when they did, it was to deflate listener expectations with a single dial tone on the Onda 400 45rpm EP.) Posters, lyric sheets, and even audience questionnaires were designed for the project, whose methods veered mischievously close to the 'hype machine' of the mass media: The Mind Invaders simply took things one step further by 'hyping' an immaterial band rather than an actually existing band that was short on substance. The "band" was, in fact, just one in a larger organization of musical entities called the Great Complotto, inaugurated by Ciani in the northeast Italian town of Pordenone in 1980.

According to Baroni, the TRAX project "was founded after a brain-storming, actually a meeting in a coffee bar one afternoon while attending a new wave festival," and, from the beginning, took a satirical stance towards the imagery and nomenclature of post-industrial society. It was decided that individual TRAX members would be referred to as "Units," each with a corresponding number ascending in accordance with the point in time that a new member joined the project (the numbers did not otherwise indicate a member's degree of "importance" relative to other Units.) In the best tradition of Industrial art, regimentation and depersonalization were utilized for means that were antithetical to further regimentation and depersonalization. A "unit" also implied a useful object whose plasticity could be further manipulated upon contact with an audience member from outside of the TRAX circle. Modern life was already filled to bursting with "units" for storage, refrigeration, heating, calculating, waging war, etc.- so why not a "creative" unit as well? Referring to the TRAX membership as, say, "operators" may have successfully conjured a similar post-industrial atmosphere, but it was the attractive ambivalence of "unit" - which could apply to inanimate objects, single humans and groups alike - that successfully conjured a post-industrial climate in which media of exchange were once again possible. The "modular" approach of the TRAX Units aimed to illustrate what was possible with networked art, while simultaneously initiating this art. Baroni believes that it is impossible to critique the aims of networked art by assessing a single artifact, which is "just a fragment of a process or performance in progress, a page of a diary…a phrase extrapolated from a logical narrative" and that multi-artist exhibitions of such should be seen as a single work. Expanding on this concept, Baroni says that:

TRAX also tried to instigate interferences and collaborations among the authors, so that the final “modular product” would be as much about networking as a by-product of networking tactics (the vinyl album TRAX - Xtra of 1982 is a good example of collective creation.)

The modular approach allowed for "central Units" within different countries to - in the spirit of the foregoing Lt. Murnau project - use the TRAX brand to fashion their own meta-communications. Although a look at the TRAX roster from the '80s shows a large percentage of Units residing in the native Italy of Baroni, Ciani and Giacon (166 Units out of 536, all told) this was never to be seen as the central base for the project. TRAX was also not the only period project to take this approach (the parodic cult Temple Ov Psychick Youth envisioned a situation where several different versions of its 'musical propaganda wing,' Psychic TV, would be playing simultaneously in different locations.) However, the modular theory animating TRAX led to a, yes, paradoxically uniform design sensibility distributed among their physical products- a clean and uncluttered look that one would expect to see on corporate communications or the monochromatic packaging of "generic" food items. Baroni recalls that:

…the TRAX graphics, after the imprint given by Piermario Ciani to early products, tended to be very neat, bold black and white, a bit cold and hi-tech: to suggest a mass-produced product, even if it was a limited edition of a few hundred copies or less. It’s a bit like the Fluxus kits that looked like boxes from the shelves of a supermarket, yet included small hand-made artists’ publications and objects.

These releases, consisting of everything from a bag of unedible [polystyrene] "crisps", to the multi-media boxes containing compilation tapes, comics, and printed materials, helped to defuse another criticism of networked art projects- that they, without exception, lacked cohesion and discipline. If the myriad practices from stamp making to cassette collaborations were more of a "process" than a "product," didn't that mean nothing would be excluded as long as it made an attempt at expressivity? Baroni doesn't seem to think so:

I do not think that the “democraticity” of networking should get in the way of the quality of the product you offer for sale: who could be happy about buying (or trading) an “open” but lame audio compilation? TRAX wanted to involve the greatest possible number of people from all the corners of the world, yet retaining a quality standard and a commitment to the proposed theme.

Attentive readers will note how here, for the first time, there is mention of making the TRAX products available for public consumption: wasn't networked art supposed to be a trans-national barter economy? Baroni explains in more detail:

Contrary to the “unwritten rules” of mail art, we were producing items intended for sale (even if we never really made any money out of them, we barely covered our costs through the sales) and we were making a selection of the participants, according to the taste of the TRAX Unit curating a certain item. For each TRAX project, we would invite only those contacts that we thought would be more appropriate for the given theme.

What goes unsaid here, however, is that the very nature of the network, then as now, allows for these kinds of "network-within-the-network" situations, whereby individuals connected via the larger network can splinter off and form new cells, bands and so on. By doing so, the splinter groups have not betrayed the parent project (which, unlike many proper "movements," never demanded exclusive fealty, anyway.) This was the ingenuity of TRAX; that its own "modular" character was just a microcosm of a network that already behaved in this way, whether all its participants acknowledged that fact or not.

Starting with the writings of Marcel Mauss, the potlatch ceremony of the Kwakiutl tribe in British Columbia has become a fashionable point of reference in critical circles: while the exact origin of the term is disputed, it is commonly agreed upon that this ceremonial feast involved the "giving away," or even destruction, of lavish gifts with no explicit demand that the gifts should be returned. Even though it was implied that a failure to reciprocate would result in a serious loss of face, the radical suggestion of the potlatch ceremony was that the gift givers could survive perfectly well without these symbolically or literally destroyed possessions. Baroni's various networked art projects capably share this spirit of art-as-gift: like the original potlatch, there is a sense of extreme confidence that once creative ideas are "given away," new permutations on the original ideas will "return" the favor with interest. Things do not always work out for the better, but then again, Baroni has never hoped for the kind of utopia where things become cumulatively better and then abruptly stop- the "utopia" or ideal state of networked art lies, rather, in its incompleteness. Since this form of creativity uses social situations as its canvas, a "finished" work would be a very somber one indeed.

Thomas Bey William Bailey is a multi-disciplinary artist and cultural researcher, whose work has manifested itself as books, articles, music releases, sound installations, experimental radio shows, and completely undocumented or personal creative actions / interventions. He has lived and worked in Japan, Central Europe,and Chicago, struggling to overcome the psychic fatigue which is endemic to our 21st century congestion culture. His work critiques and frames this culture by avoiding the obvious, easily perceptible middle ground and instead focusing on 'micro' and 'macro' aspects of lived experience in an information-saturated epoch. To this end, Bailey's work tends towards either 'atomizing' life (e.g. making recordings of asthmatic breath and incomprehensible sleep-talking, strobing videos limited to only a couple visual elements) or illuminating its hyper-complexity with intense noise, etc. It is a celebration of 'life before death' and a valuation of intimate, inter-personal exploratory nature above mass techno-philia or techno-phobia. Many of these ideas are further fleshed out in Bailey's first book-length survey of his influences and allies,"Micro Bionic", published 2009 on Creation Books. This essay on Vittore Baroni is adapted from a chapter in his book-in-progress "Unofficial Release: Self-Released And Handmade Music In Post-Industrial Society."