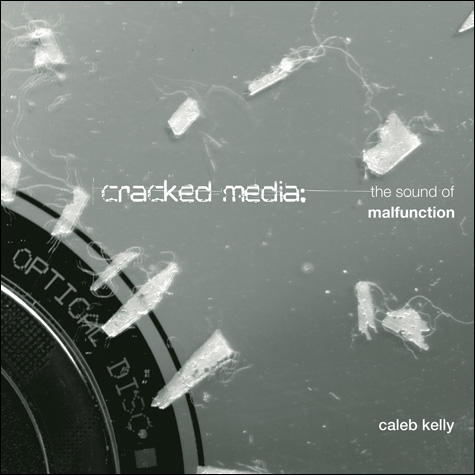

Many scholars within the field of media archaeology opt to focus on the backstory behind an influential medium or technology and map out how its inception and organizational logic (re)shaped the world. An alternative approach is the excavation and arrangement of fringe/forgotten prototypes into an array to problematize dominant historical narratives regarding technological progress. Caleb Kelly's recent text Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction uses two consumer technologies, the phonograph and the compact disc, to survey 20th century musical and artistic production. The book catalogs a broad range of experimentation with these playback technologies to create detailed timelines of misuse and critical engagement. In bracketing this realm of sound-producing practice, Kelly proposes "cracked media," a subversion of technological devices whereby "...tools of media playback are expanded beyond their original function as a simple playback device for prerecorded sound or image." Given the prominence of the glitch and lo-fi malformed digital artifacts everywhere from media art to pop music to web video, it is easy to take the aesthetics of failure for granted. The investigation executed within Cracked Media prefigures many of the discussions that underpin generative and glitch aesthetics by focusing on work that foregrounds and interrogates the materiality of two specific mediums. Kelly methodically tracks projects that subvert the CD and phonograph over the entire 20th century and in doing so he builds a fascinating discourse about musical performance and reproduction that is equally comfortable referencing Friedrich Kittler as DJ Qbert.

One of the questions at the core of Cracked Media is "how many times can you force something into failure before it becomes creatively uninteresting?" Kelly suggests that key projects by artists such as Christian Marclay and Oval provide us with a variety of approaches for "manipulating, cracking and breaking" media. This takes us into a realm of creative interventions that range from temporary hacks to CDs and vinyl records (eg. the application of tape to the playback surface) to more dramatic (and permanent) alterations such as scratching to outright disassembly. A taxonomy of alteration and damage is developed and Kelly proceeds to consider these strategies as a gateway into the critique of musical production and consumption. Cracked media is imbued with a new performative capacity, one that revels in noise ("extraneous information") as an inevitable occurrence and as a raw material for new construction. The subsequent two chapters telescope out of this discussion of noise and are written as extremely detailed chronologies dedicated to each of Kelly's chosen mediums.

According to Kelly, the phonograph is one of the most enduring musical artifacts of the 20th century and the author succinctly contextualizes how the device operates for passive playback and can also be harnessed as an instrument. Cutting from hip hop culture to a 1914 performance of Erik Satie's Le Piege de Méduse, he then proceeds to list a number of instances of "prepared" instruments and early compositions involving turntables then transitions into a detailed examination of sound and the Fluxus movement. This discussion contains summaries of early work that includes "Neu Musik Berlin," a 1930 turntable concert organized by composers Paul Hindemith and Ernst Toch, John Cage's prescient Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939) and Cartridge Music (1960) and Nam June Paik's Random Access (Schallplatten-Schaschlik) (1963). The momentum generated through examining these precedents leads into analysis of the turntable-based work of Milan Knížák, Christian Marclay, Otomo Yoshihide, Akiyama Tetsuji, Michael Graeve and Lucas Abela.

Upon the release of CDs in the early 1980s, it quickly became apparent that many of the strategies for tampering with the phonograph and vinyl records lent themselves to undermining the "frictionless" laser playback system driving CD technology. Kelly applies the same rigor described in the preceding paragraph to survey work by Yasunao Tone, Nicholas Collins, Oval and Disc. In one of the most lucid passages of the text the author compares the assembly, operation and audio "encoding" of the phonograph to the CD player to highlight the opportunities presented by this newer digital platform. This discussion cites some early consumer reviews that expressed a marked skepticism regarding the durability of CDs. Kelly here describes the similarity between the reviewer and the cracked media practitioner:

What this demonstrates is a common interest between artists and the reviewer who tests a new technology by forcing it to fail. The manufacturers and developers had created a new form of technology that was said to be able to correct both errors and damage done to the discs. In reaction a reviewer sought to find out exactly how good the new system is, how hard will it be to prove it fallible, and what exactly will happen when it does fail. He does not see this process as anything more than a conscientious reviewer doing his job. (Pg. 226)

This comparison is a perfect point of entry for the "wounded CDs" of Tone and the clinical experimentation of Oval. Kelly devotes considerable attention to the latter of these artists and tracks the "quintessential CD glitch band" from their first experiments with CD manipulation in the early '90s through their critically acclaimed Wohnton (1993), Systemisch (1994) and 94diskont (1995), which started out exploring the curious intersection of cracked media and pop music and moved towards an even more media-savvy formalism.

Cracked Media concludes with a (needed and refreshing) chapter dedicated to grounding the above medium-specific practices in everyday life. Invoking Michel de Certeau's discussion of "tactics," cracked media artists are framed as playfully wandering beyond the prescribed boundaries that demarcate the acceptable use of consumer technology. Kelly attempts to connect his exhaustive analysis of material-based media manipulation with the nebulous milieu of "post-digital" audio production, but these motions are tepid compared to the rest of his research. This is not a dismissal of the final act of Cracked Media as it is only fitting that a text that fixates on entropy, rupture and obsolescence conclude with a nervous uncertainty. Given Kelly's appraisal of the materiality of the phonograph and CD throughout the 20th century, exactly where would he (or another author) apply that attention now? Antagonistic software studies that dissect the virtual studio? A careful consideration of the compression algorithms of the MP3? Or perhaps a speculative examination of emerging tangible interfaces and/or controllerism? Thankfully Cracked Media is not a polite book about pluralistic remix culture, it is a comprehensive archive of the "actions" of media artists who weren't afraid to get their hands dirty.

Greg J. Smith is a Toronto-based designer with an active interest in the intersection of space and media. He is co-editor of the digital arts publication Vague Terrain and blogs at Serial Consign.