Independent, Chicago-based collective Temporary Services, comprised of Brett Bloom, Salem Collo-Julin and Marc Fischer, have been producing exhibitions, events, projects, and publications since 1998. More recently, they published the newspaper and website “Art Work: A National Conversation About Art, Labor, and Politics” which assembles writing by artists, activists and academics about the economic decline and its influence on the livelihood of artists. (I previously posted one article to Rhizome from this collection, "Art Versus Work" by Julia Bryan-Wilson.) I had the opportunity to interview Temporary Services over e-mail, and they answered my questions as a group via Google docs. - Jenny Jaskey

This post is the concluding article in a series on art production and economy. To read the other articles in this series, go here for an interview with Caroline Woolard of OurGoods and here for an interview with Jeff Hnilicka of FEAST.

How did Temporary Services begin?

TS: We began in 1998 as a storefront space that presented experimental art projects and exhibitions. In late 1999 there were several people collaborating in and around Temporary Services. We decided to form a group. Since that time, the group has fluctuated in membership to arrive at the current configuration of Brett Bloom, Salem Collo-Julin and Marc Fischer, which has been stable since 2002.

Your most recent project is a paper and accompanying website, "Art Work: A National Conversation about Art, Labor, and Economics." What led to its development?

TS: We were invited by Christopher Lynn, the director of SPACES Gallery in Cleveland, to organize an exhibition. SPACES is an important art organization that has its origins in the nationwide alternative art spaces infrastructure built in the 1970s, and funded in part by a more adventurous National Endowment for the Arts than the one that exists now. We were surprised that we were offered a decent budget by SPACES, and wanted to do more than just make a show. We were heavily impacted by the economic crisis, as were many of our peers. We were excited by the incredible nose dive that sales in the art market took, which we believe weakened the control of the market over discourse and resources in the United States. These factors, combined with the horrendous situation in both how universities are being privatized (many schools are effectively being turned into tools of the cCorporate world) and in that most people who graduate with art-related degrees are left with massive debt and no reasonable possibility of getting a job that pays well and gives them health care. The situation for artists in the U.S. is abysmal. We think that this is the prime time to ask a lot of questions, look at our collective histories, figure out what people are doing to survive, and, in general, to start a nationwide discussion about what we can all do to make a different situation.

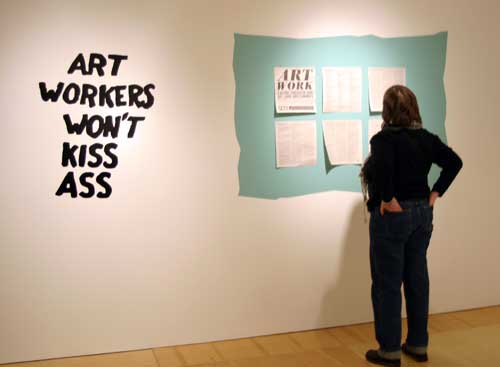

How do you see your organizing efforts in relationship to earlier movements of the 1960's and 1970's, groups like the Art Worker's Coalition (AWC)?

TS: We are inspired by Art Workers' Coalition, but also by many other groups from that time, as well as art and labor workers' efforts in the 1930s. We are also inspired by more recent efforts to create innovative infrastructures of support that are not corporate, governmental, or even non-profit. The landscape has really changed. We have a funny situation where artists are more necessary to our culture than ever before, and yet they are the most exploited and marginalized economically.

Maybe this is really obvious, but it's important to distinguish that AWC had a particular set of goals that a large group of people rallied around for a short, concentrated period of time. We share many of their values and it's a perfect time to re-explore their ideas. However, the larger work of Temporary Services is extremely eclectic, and more concerned with group work over a longer duration and greater variety of themes than a focused, directed attack about a single subject.

There seems to be an emphasis on groupwork and non-competition in your work. Do you see individualism as antithetical to artistic or social progress?

TS: You only have healthy individuals if you have a healthy collective. The inverse of this statement is true as well. Our society slants way too much towards individuals at the expense of the collective. There are serious consequences for this.

Every art piece ever made requires many, many people to bring it into existence and public view - every art work is collaboratively produced. The problem comes in when power and interest in making money starts to control the conditions around how art is made and how it shows up socially.

The commercial gallery system is almost totally concerned with artists who are credited as individuals (even when they have massive teams of assistants) and very rarely with artists that work as groups. Because we, and many others are not part of that world, we have to come up with other support structures and strategies for circulating our work and the work of others outside of that system.

The commercial gallery system by and large exploits artists - either directly through selling and reselling artists' work to the kinds of people who can afford it, or through relying on a system where everyone expects or hopes to have access and can't. It only benefits a small number of artists, gallerists, and collectors. It is not a system that provides well for the enormous number of practicing artists. It also dramatically limits how art can be conceived of and where it shows up in the world.

One of the more moving sections of “Art Work” were the anonymous Personal Art Economies, where artists and arts professionals detail the ways they fund their lives and careers. I have always been struck that artists are some of the only professionals in the world that consistently work for free out of passion (and often pay to work). What is your view of the artist as worker?

TS: The paper is not a debate on whether art is "work" or how it is theorized. We are more concerned that the labor of artists (including the production of their artwork, the teaching they do, the lectures they give, the writing the push out, and so on) is often exploited for the economic gain of others. Our concern is about creating a new language and methodology around art *and other creative fields* that sees this output as essential to the daily life of humans. How do we continue to create this work and sustain ourselves and others? How do we insure that our output is not used by others, knowingly or unknowingly, for their personal or corporate gain?

In general, we want to get rid of the idea of work for everyone. We believe that people from all fields can work together in order to create an environment that takes care of everyone and is not dependent on the outdated model of Capitalism. It's not just about the very real conditions that often require artists to be "wage slaves" in order to have time and resources to make their artwork.

There needs to be a larger conversation about what art is. It isn't labor or work. It's not a novelty or something that just happens because people have nothing else to do. We think that art is something more basic and necessary for humans to function. Commercial interests obfuscate this. We tend to forget that art in its current form as a commodity is a very recent invention, and not a given absolute.

Do you have a vision of what it would look like to be an artist full-time, while avoiding the art-as-commerce model?

TS: One example is the Works Progress Administration in this country, that created jobs for artists to do meaningful work and make a living from it, while simultaneously helping the nation rebuild its image and infrastructure through murals, posters, paintings, public works projects, poetry, and so on.

Our European counterparts have access to larger amounts of funding and can get support for non-commercial projects. Putting together several sources of revenue from exhibitions, presentations, workshops, and long-term projects is part of how we survive - but we could do this exclusively if we were actually paid well for what we do. We have to have other jobs. But we can see a slightly different situation where this could start to work.

Harrell Fletcher has a short article in the Art Work paper about standardizing lecture fees for artists. This is just one thing that could take us in the direction of a better situation for artists.

Would you support the integration of the artist into the traditional workplace, serving an overtly "artistic" function within an office?

TS: If we could do it in the style of Mierle Laderman Ukeles! In general, we fear that in these situations artists can lose their creative freedom and be instrumentalized by concerns that are not their own. If truly collaborative situations were created, then that might be interesting. It's hard to imagine a job where every co-worker would be a desired collaborator. The freedom afforded by working in self-initiated groups is hard to match.

Millions of artists are definitely serving a covert artistic function within offices - working on personal projects and texts on someone else's watch, editing their writing, emailing about their exhibits, updating their blogs, using office equipment, and many other vital functions of daily artistic life. There is something to be said for having no creative responsibilities in a job if it pays well enough and leaves enough mental space and physical energy to work on things that are more meaningful. Sadly this is not often the case.

Nonetheless, non-creative jobs are sometimes excellent incubators of artists and artist projects when employees have enough down-time to talk and plot future work with their similarly struggling co-workers. It would be interesting to know just how much creative work gets made at the expense of a workplace that is not specifically employing artists for their creativity.

One way that artists are re-thinking their relationship to capitalism is through bartering and gift economies. Carolina Caycedo, OurGoods, FEAST, Sweet Tooth of the Tiger, W.A.G.E., and others have demonstrated these strategies. What do you see as the benefits and limitations of these models?

TS: All of these projects are important and necessary, but unfortunately, none of them individually can operate on a scale that fully challenges the power of a capitalist-based society. They also don't individually produce vast community wealth (and here we are not talking about greedy-Oprah-Bill-Gates-sized individual wealth) and resilience - a lasting, robust, strong support system. Some of these initiatives and projects may grow into this. We are excited to enter the future world where all of these people and initiatives can collaborate on parallel projects that work alongside people in other places and fields to create a new idea of economy.

As Temporary Services, you wear many hats, serving as artists, political organizers, curators, and critics. Do you distinguish (or recognize) when you are doing "art" and when you are doing something else? Why are these divisions important or not important to you?

TS: We don't have any need to make distinctions like these. Our art practice is not confined by traditional, limited conceptions of artistic production. It is when distinctions are carefully made and circumscribed that you start to get hierarchies of meaning and access. We are really excited by how the boundaries of art are breaking down and we seek to push that further with our efforts.

What is a primary way you hope to see the relationship between art, labor, and economics change in the coming decade?

TS: It would be really great if a majority of artists stood up for themselves against their exploitation. We would like to see museums and universities become more public and less private (privatized). We would also like an ever-diminishing role of exploitative commercial control over art discourse. We also must build counter-institutions and counter-narratives about how and what art can be and do. There is tremendous, untapped potential there. We believe in the power of people to sustain each other. We have much hope that humans will evolve into a non-competitive, non-exploitative, caring, sustaining race.

What are some resources for readers who want to learn more about art, labor, and politics?

TS: Check out the print and digital bibliographies on www.artandwork.us and you should find tons of reading material.

Throughout January and February, independent spaces around the United States will host events to launch the paper and discuss the issues it raises. Check below for an event in your area, and check the artandwork.us website for updated listings.

ABC NO RIO, New York, NY, TBA

basekamp, Philadelphia, PA, February/March 2010

Commons Gallery, University of Hawaii, Manoa, March 22 - April 2, 2010

CS13 Gallery, Cincinnatti, OH, March 2010

Dalton Gallery, Agnes Scott College, Decatur, GA, TBA

Gallery 400, Chicago, January 27 - March 6, 2010, Public Discussion on January 30th, 6-8 PM

McLean County Art Center, organized by Brian Collier and Alison Hatcher, Bloomington, IL, January 15 - February 20, 2010

Miller Gallery, Carnegie Melon Univeristy, Pittsburgh, PA, February 2010

Skydive, Houston, TX, January 23 - February 27, 2010

Trade School, Brooklyn, NY, February 25, 2010, 6-9 PM

W&N, San Juan, Puerto Rico, TBA