Installation view of Wet Networks at the Queens Museum, 2022. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

A special event relating to “Wet Networks” will take place at Queens Museum this Sunday, May 1, 2022 at 12pm ET.

“Wet Networks” is an exhibition at the Queens Museum (ongoing through August 14, 2022) that features artifacts and projects from Geek Camp 2021: Neversink Never Ever, organized by Rhizome and CycleX.

Taking place in July 2021, this “Geek Camp” was envisioned as the first in an annual series of convenings initiated by artist Shu Lea Cheang at CycleX, an experimental farm and cultural center located in what is today known as the town of Andes, New York.

As curator of the inaugural camp, I invited six artists—Tecumseh Ceaser, Nabil Hassein, Melanie Hoff, Christopher Lin, Jan Mun, and TJ Shin—to consider Cheang’s prompts to walk the trails, consider the ebbs and flows of the reservoir, and engage waves as carriers to recall buried sentiments of displacement and relocation. They were joined by Erwin A. Karl, mycologist and Evan T. Pritchard, Founder of the Center for Algonquin Culture. Together their reflections and offerings illuminate the relationships between new technologies and traditional ways of knowing, the challenges of collective care, and how land and water shape and are shaped by one another and us.

Working individually and collaboratively with support from the Rhizome Commissions Program, the participants developed artworks and other projects that are on view in the Queens Museum’s Watershed Gallery. Documentation and descriptions of each project can be found below.

Installation views of Wet Networks at the Queens Museum, 2022. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Jan Mun and Tecumseh Ceaser

Jan Mun and Tecumseh Ceaser, 224g, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Ganoderma applanatum (artist's conk) mushroom with carvings by campers.

The artist’s conk mushroom is known for its soft, white underside which easily scratches away to reveal dark brown tissue. It hardens when dried, making it an advantageous medium for drawing. This mushroom, initially weighing 410g, was found during a hike near N42° 10.503' W074 43.000'. It was collaboratively carved by campers during their stay at CycleX, with additional connective carvings made by Tecumseh Caesar. As a result of this reshaping, and a loss of moisture over time, it now weighs 186g; the title refers to the difference in the mushroom’s mass before and after the collaboration.

Christopher Lin

Christopher Lin, Soft Core Memory, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Earth, rocks, and microfauna (earthworms, isopods, and springtails) from CycleX, activated carbon, water, compost, cotton flag, stress relief toy, antique brass buttons, wampum beads, quahog clam shells, glass vessels, vents, rubber, wood, shelves, time. Wampum beads created and advised by Tecumseh Ceaser (Native Tec).

This living sculpture contains bioactive earth collected from CycleX. Each vessel holds a biome consisting of detritivores (earthworms, isopods, and springtails) and beneficial bacteria which consume and transform decaying organic matter into rich soil for growth—an active vermiculture ecosystem.

Unlike the compressed and hardened mineral core samples extracted to examine geologic history, these core samples are soft and alive. A colonial flag, brass buttons with the New York State seal, lengths of wampum beads, and other symbolic artifacts are buried at various depths. Over time, the objects decay as they are digested into new soil, processing an amalgam of contentious histories in a composting mechanism.

Jan Mun

Jan Mun, Interspecies Cooperation: Mycorrhizal Mudballs for Simard, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Douglas Fir and Birch lumber, acrylic, artist’s hair; soil and water from: N42° 10.525' W074 43.006' Elev +1768 ft, N42° 10.902' W074 42.984' Elev +1740 ft, N42° 05.536' W074 49.175' Elev +1766 ft.

This installation features dorodango, or polished mud balls, made from soil and water from CycleX, a nearby hilltop pond, and the Shavertown Trail at the Pepacton Reservoir. The soil from these locations contains mycorrhizal fungi.

According to Dr. Suzanne Simard’s groundbreaking research, mycorrhizal fungi have been found to foster communication and share resources between Douglas fir and birch trees. By facilitating the exchange of carbon, water, nutrients and more, these underground fungal networks demonstrate social entanglements, like human relationships. Mun has selected lumber from these two tree types to create the shelves where the mud balls sit. The arrangement of these elements on the wall is modeled after shelf mushrooms growing on trees.

Nabil Hassein

Nabil Hassein, CycleX Reflections, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Risograph publication, Edition of 300. Designed by Neta Bomani. Edited by Nabil Hassein and Celine Wong Katzman. Map and images courtesy Erwin A. Karl and campers.

Essays included:

Geek Camp 2021: Neversink Never Ever by Shu Lea Cheang

Mycorrhizal Memory by Nabil Hassein

Mucking, Mattering,and Bone by TJ Shin

CycleX Reflections is available to read online.

Melanie Hoff

Melanie Hoff, FAILURE<>COLLAPSE<>YIELD<>CATALYZE, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Chrome 99 on Linux. Website.

This is a work of folder poetry: the practice of using the structure of computer folder organization to make unfolding narratives and rhythmic prose. In this folder poem, Hoff's experience at Geek Camp serves as a point of departure to explore the tension between the harmful histories and liberatory potential of language. They ask: "How can we have a beautiful transformation and collective renewal that isn't preceded by catastrophe?" Hoff invites reflection by feeding a computer program they wrote "seed words" from the poem. The program then recursively generates synonyms that reveal unexpected connections and linguistic evolutions, as in the title of the work. This process is made visible by screen recordings of the artist’s computer terminal running the program, which have been placed within the poem.

Melanie Hoff, Garlic Network, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Garlic, jute rope.

This garlic was planted by the artist with Rhizome in November 2020 and subsequently harvested in a group activity with campers at CycleX during Geek Camp. After the harvest, Hoff hung the garlic to dry and then wrapped it in rope.

Erwin Karl

Erwin A. Karl, Flora for CycleX, 2018-present. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Spreadsheet containing records of flora and fungi at CycleX running on Chrome 99 on Linux.

“Like many land stewards and farmers, I had considered plants that self-propagate as weeds, despite having foraged a number of wild plants for many years. Implementing permaculture projects has given me the opportunity to study the plants and volunteer fungi; investing time in studying how they grow, identifying species, and researching edibility and medicinal properties from print and online resources has been rewarding.

The species change from year to year, and not all my IDs are accurate. After four years, this remains an evolving work-in-progress.” —Erwin A. Karl, Site Manager and Technical Director at CycleX, Andes, NY

A version of this spreadsheet is viewable online.

TJ Shin

TJ Shin, Landscape (Rondout-West Branch Tunnel), 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Bone char pigment, linseed oil, gum arabic, bone char, sand, plexiglass. Bone char produced in collaboration with Erwin A. Karl.

TJ Shin's Landscape works are water-filtering dioramas featuring images sourced from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection Protection archives. During their stay at CycleX, Shin fired found animal bones to produce bone char, which is commonly used as an activated carbon filter. Some pieces are on display in the dioramas, and others were ground into pigment to produce the lithograph backdrop images.

Examining the labor conditions under which the New York City Water Supply System was constructed, Shin explores how the act of filtration—the process of purification—is entrenched in the grammar of extractivism.

Evan T. Pritchard

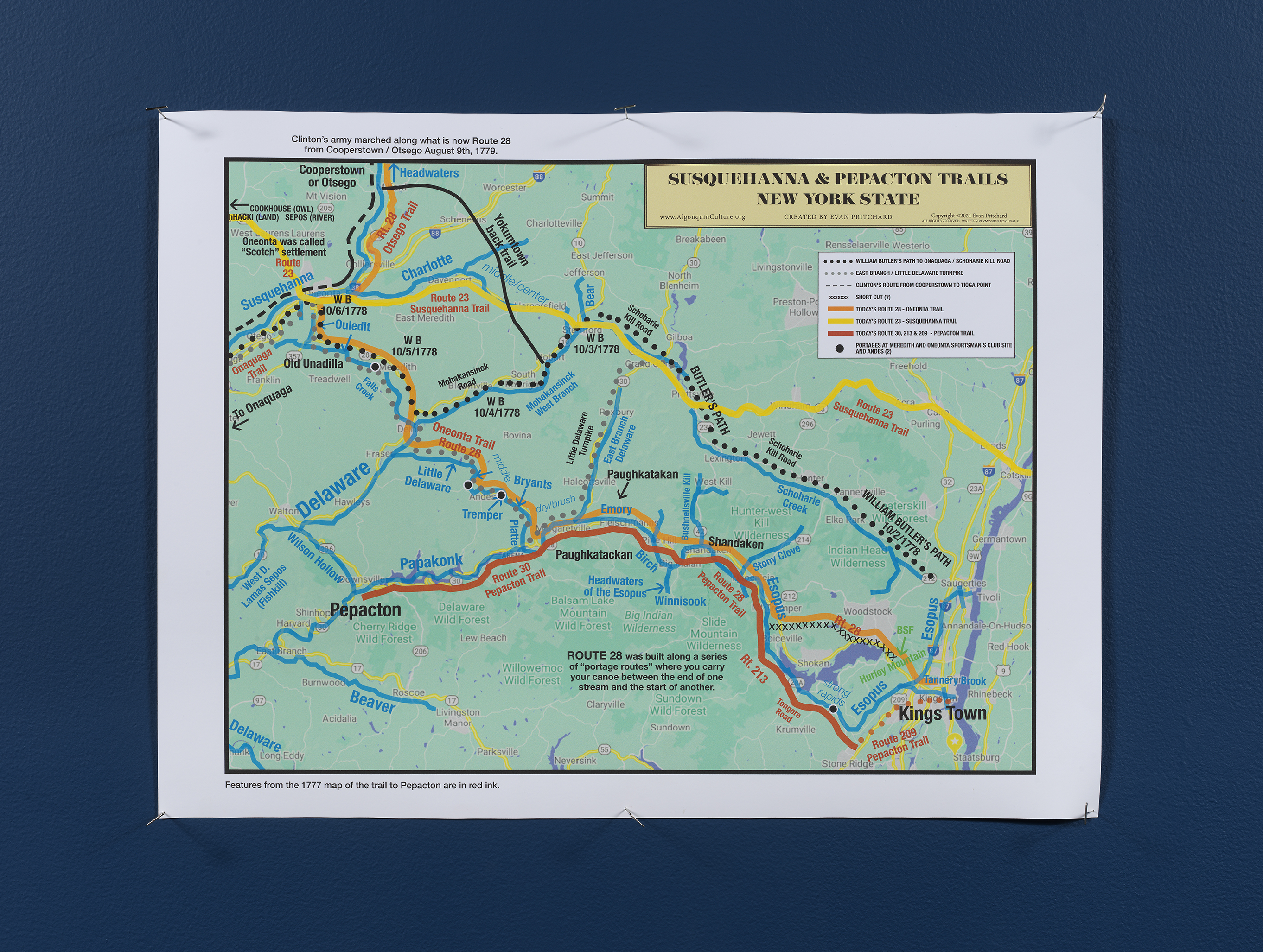

Evan T. Pritchard, Susquehanna and Pepacton Portage Trails, 2021. Courtesy of Rhizome. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Digital inkjet print.

Evan T. Pritchard, the founder of the Center for Algonquin Culture in Rosendale, NY, produced this map of Native American portage trails based on his own research. Many of these trails were formed into modern highways. He explains:

“Thousands of years ago, Native American traders traveled the approximately 125 miles of mountainous terrain between what are today known as the Hudson and Susquehanna Rivers. They journeyed on foot and by water, and also by a combination of both, carrying their birchbark canoes over the land between rivers and streams. This third method was one the French trappers later called portage.”

Smaller tributaries spread out like a network from the main branches, creating surprisingly simple connections between rivers. There are never more than two or three miles of dry land between the creeks where travelers would portage canoes, which can be seen on the map alongside Routes 23, 23A, 28, and 30.

Credits

The 2021-2022 Rhizome Commissions Program is supported by the Jerome Foundation, American Chai Trust, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislation.