“When she was just a girl she expected the world,” sings Chris Martin. “But it flew away from her reach.” During the first verse of Coldplay’s 2011 hit “Paradise,” the listener learns that the character whose story he narrates “dreams of paradise.” By the second chorus, the phrase changes on a deictic turn: “This could be paradise.” Total bliss is spatially configured as both everywhere and nowhere. During both choruses, Martin shifts from the third-person narration employed during the song’s verses and sings in free indirect style: from the caesura between first- and third-person narration, where they entangle.1 In this position, his authoritative speech is simultaneously able to inhabit, and slip back and forth between, omniscience and partiality. Paradise is not just “hers,” but also Martin’s, and implicitly, the listener’s. The chorus compels the listener to sing along: it addresses a “we.”

Popular music thrives in the nominative plural: “We will rock you.” “Just hold on we're going home.” “We can't stop.” A hypothesis is shown leniency in the context of a chorus, taken with a grain of salt; its claims are not strictly logical. And yet, a chorus also seeks axiomatic status: what is sung should be true. More often than not, popular music’s “we” is implicit: the artistic form is thought to be for everyone. Despite this speech act’s ubiquity, its universal aspirations are often challenged because some things are not shared. The basic premise of Marxism remains deeply troubled along these lines: are “we” truly fellow travelers? Can we be?2

In the genre known as EDM, the “we” is inescapable. Martin Garrix’s compellingly ugly “Animals” features just one lyric, “We are fuckin’ animals,” and its pneumatic tuned percussion has soundtracked the drop of countless viral videos. Skrillex and Sirah’s “Bangarang” also features just one chopped up lyric: “Shout to all my lost boys / We rowdy.” DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down For What” is designed specifically for social spaces like clubs and the radio, and its message is designed specifically for an imagined community of partiers; the same goes for Flux Pavillion’s “I Can’t Stop,” Fatboy Slim and Riva Starr’s “Eat Sleep Rave Repeat,” and innumerable other EDM hits. Consider also Rihanna and Calvin Harris’ “We Found Love,” as well as Alesso and Tove Lo’s “Heroes (We Could Be)”: these songs are powerful precisely because they transform two individuals’ romantic narrative into a plot where collectivity is at stake and the song feels like more than just a song. The popularity of this style of musical storytelling hinges on a wager that if one uttered the phrases “we could be heroes,” “we found love,” or “this could be paradise” enough times, they might just become true.

Coldplay’s “Paradise” was a hugely successful single in its own right, but it was also remixed into a significant EDM hit by Dutch producer Fedde Le Grand in 2011, the same year that the original song was released. The song’s ability to catalyze a crowd was palpable when it was played in a mix by Swedish House Mafia’s Sebastian Ingrosso and Alesso –two of EDM’s biggest artists– recorded live in August 2012 at the iconic and Guinness World Record-breakingly large club Privilege Ibiza. Le Grand’s remix and the Privilege dancers’ accompanying singalong marks one of the most memorable moments in this set, later released as an Essential Mix for BBC Radio 1. When Chris Martin makes his appeal to the good life—as constituted by joyous and celebratory collectivity—in this remix, during this DJ set, in this location, at this time, broadcast to the world, it is loaded with meaning. The euphoria it sought to produce was incredibly potent–though vague and ahistorical–and completely indicative of the tendencies of EDM as a whole.

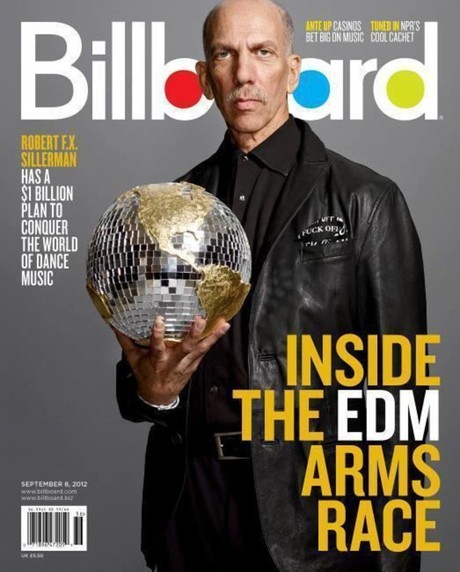

The height of EDM’s popularity was carnivalesque in the extreme, and the EDM moment was characterized by unbridled big business, high-intensity partying, and escapism. That same month that Alesso and Ingrosso’s mix was recorded, Forbes placed Swedish House Mafia in third place on their first edition of the now-annual Electronic Cash Kings list of the world’s highest-paid DJs, behind Tiësto and Skrillex. Then, a month later, an American businessman appeared on the cover of Billboard magazine holding a disco ball. The story’s title: “Robert F.X. Sillerman has a $1 billion plan to conquer the world of dance music.” EDM DJ Afrojack joined Sillerman a year later to ring the NASDAQ closing bell in celebration of SFX Entertainment’s initial public offering on the stock market at $13 a share. While the affinities between EDM and finance may not have always been obvious, they were now beginning to definitively coalesce.

The social practice of raving to electronic music did not have its origins in the financial sector, nor were the styles of music that anticipated EDM–house, techno, UK hardcore of various shades–created to be played on yachts via Sonos bluetooth setups. In contrast to EDM’s central role within popular culture during the early 2010s, electronic club music had its beginnings as a sharply differentiated and distinctly underground subculture. For many artists and dancers, early club music spaces were a utopian reprieve from the harsh conditions of reality; the rave offered a potent site for dreaming up whole new ways of being. Whereas the beginnings of rave culture looked to manifest the exciting possibility of another world, Le Grande via Swedish House Mafia and Martin’s euphoria did not pretend to think that another reality was possible or necessary.

Instead, it sought to be ahistorical in the most concrete sense, ignoring the many simultaneous crises that colored material conditions outside of the club. Despite Swedish House Mafia and Martin’s attempt at disavowing reality, though, the song reads like an inverse form of strict social realism, highlighting all the chaos, extraction, and depravity it seeks to ignore: there’s an earnest, almost endearingly naive melancholy in Martin’s vocal performance, like that of a child who doesn’t know why he’s sad. At this point in history, everybody knows that this is definitively not paradise. And yet, people sang along. In retrospect, it is remarkable how thoroughly EDM imbricated itself as a main pillar of popular culture, remaining truly inescapable for the better part of a decade.

Upon further investigation, though, It is no accident that EDM rose to popularity immediately following the financial crisis of 2008. The culture surrounding the genre offered a highly effective set of conditions and practices for millions of people seeking to recuperate affective and libidinal deficits incurred by the extractive logics of the ongoing financial crisis. Ultimately, EDM also replicates the financial political economy that structured its very existence as well as its effects on subjects.

Surely EDM thrived because people enjoyed listening to it, but the cash flows that facilitated the genre and its market bubble – where exactly can we say that one ends and the other begins? – need to be understood as part of finance’s historical context tracing back at least forty years. For our purposes here, we’ll begin in the 70s, when new information and telecommunication technologies started changing the global economy. The industrial mass production of Fordism was replaced by the “immaterial” regime of post-Fordism in overdeveloped countries, and simultaneously transnational corporations became the dominant force in global production and international trade. Perhaps most importantly, beginning in the late 70s and persisting in the following decades, the financial sector and its accompanying, wildly influential logic have flourished while enjoying substantial deregulation. Economist Costas Lapavitsas has identified this period’s “unprecedented expansion of financial activities,” exemplified by the rapid growth of financial profits, extensive financialization of the economy and society, and domination of economic policy by the interests of the financial sector. Meanwhile, inequality has skyrocketed and crises have occurred more often and with greater intensity.

These functions belie the fact that financialization is predicated on “risk rationality,” as “Ontology of Finance” author Suhail Malik calls it. It has been argued that, beyond the far-reaching material effects of financialization, one of financial capitalism’s most significant achievements is the reorganization of society’s relationship to the future.4 Under financial capitalist logic, capital-power is not reliant on labor, but is exerted through pricing predicated on finance, which determines the relationship between the actual and the inactual through the process of time-binding which do not answer to any notion of absolute, “objective” time. The underlying asset in derivatives trading becomes basically irrelevant, aside from the price conditions set in the contract. Value becomes autonomous. This system predicated risk rationality, which is fundamentally irrational—contra traditional philosophical logic–“maintains incompatibilities rather than repelling them.” Risk rationality’s power consists in “control not over what the future will be as such (per planning), but control as the construction of possibilities for the future ‘without knowing or having to know’ whether those possibilities will come to pass.”5

Considering the extreme power of finance, politics as it exists in this regime is heavily determined by who has power over future contingency. Whereas industrial capitalists sacrifice the present for the future, reinvesting profits to increase potential future revenues, traders spend money in the present they expect to accrue at a future date.6 With derivatives, the uncertainties of the future are “used to construct prices in the present and this scrambles the standard time structure of past-present-future.”7 Given all of this, it is a comically surreal coincidence that the president and COO of Goldman Sachs, David Michael Solomon, is also an EDM DJ. DJ D-Sol’s first single was an exercise in gaslighting: a buoyant, club-ready cover of Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop,” as menacing as one could imagine. “Don't stop thinking about tomorrow / Don’t stop, it'll soon be here”…

It is in this fundamentally scrambled relationship to linear time that the perverse, euphoric “we” of EDM develops its peculiar character. The lived experience of being forced to participate in such a system– one that, since 2008, has by most accounts been shown to be unequivocally flawed–results in a chronic experience of a uniquely temporal form of alienation, both from oneself and from the social fabric—that comes with the experience of witnessing the theft of the future and feeling the fundamental structure of time bend and twist according to the whims of the financial class.

Yet, temporal estrangement is nothing new in club music. It is arguably baked into directly into the style – in the sleevenotes to A Guy Called Gerald’s 1995 classic Black Secret Technology: “With a sample you've taken time. It still has the same energy but you can reverse it or prolong it. You can get totally wrapped up in it. You feel like you have turned time around."

With some imagination, this description could be transposed onto the time-binding principles of finance-power. And yet, comparing the jungle producer’s music with EDM, the listener can hear two qualitatively different instantiations of the concrete relation between what could be and what is. EDM often feels hopelessly resigned to the impenetrable chaos of the present. The “Paradise” that Martin evokes—and which members of the Swedish House Mafia amplify and circulate with their super-powerful sonic technologies—is gripping not because it potentially describes another way of living but because it seems to offer a compelling, thorough account of anything at all. An extreme surplus of viscerally overwhelming sonic content is perfectly matched by fill-in-the-blank-style sentimentality: total fullness is able to stand in for complete emptiness and vice-versa. EDM becomes a soundtrack for the 21st century with exceptional ease, fulfilling “the desire for a time that is not in time, a unity outside history,”8 the same desire that drove the utopian ethos of rave culture, super-sized and resurfaced.

While some recent developments in finance are historically novel, it would be a mistake to describe its speculative logic as a purely contemporary phenomenon. In his text Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History, Ian Baucom identifies the Zong massacre and the legal trials that followed as a “truth-event” that sparked an “epistemological revolution,” condensing the operations of speculative reason which underpinned the systems of global finance capital and slavery, and fundamentally shifted how reality was represented in the Western world. In order for the Zong trials to unfold as they did, slaves had to be regarded not just as commodities, but as commodities subject to insurance contracts and the abstract general equivalents of finance capital. In other words, slaves were treated as dematerialized, “suppositional entities whose value is tied not to their continued, embodied, material existence but to their speculative, recuperable loss value.” In order for complex financial transactions to take place in the absence of materials goods, the relationship of the knowable to the imaginable–the real and the abstract–had to be violently redefined.9 Given that racialized violence and genocide are at the heart of the specualtive epistemology that has produced the global financial system, it follows then that the cultural forms that have come out of it–like EDM–in some way exhibit an intimacy with violence and death themselves. As a set of sonic dispositions and cultural behaviors appropriate to the post-crash meltdown, EDM begets an explicit expression of the lethality of the abstract concepts that underpin what Warren Buffet has called “financial weapons of mass destruction.”10

In the past decade-plus, there have been a truly remarkable number of highly-publicized drug deaths at EDM festivals.11 The Los Angeles Times found in a report that between 2006 and 2016, a total of at least 25 drug-related deaths occurred at parties hosted by just three party promoters.12 Working as a freelance electronic music news reporter from the years 2015-2017, I personally reported on drug-related deaths at EDM events regularly.13 In July 2012, a total of 12 people were stabbed at Swedish House Mafia concerts—Alesso and Ingrosso recorded their Essential Mix a month later. Kaskade, a very popular EDM producer and DJ, has offered the following comment on drug-related deaths: “I’m happy to tackle substance abuse,” he said. “I’m happy to use my influence to encourage people to be responsible, to stay alive. But this is a world-wide problem, something that is not even close to being unique to dance music.”14

The EDM movement found its martyr, so to speak, in Swedish artist Tim Bergling, known to his fans as Avicii, who committed suicide in 2018. Listening to his gorgeous 2011 single “Levels,” one can sense the depressive melancholy of persistent uncertainty. The song’s lyrics are at first sparse and evasive: it is about how “sometimes,” you “get a good feeling.” The vocalist is Etta James, and the sample is from the first verse of her 1962 single "Something's Got a Hold on Me.” James begins the song by lingering in descriptive ambiguity, emphasizing the alien might of the feeling she’s “never had before” by refusing to name it. This creates a tremendous amount of tension – despite the fact that it’s obvious what she’s singing about – which goes on to be cathartically dispelled by the chorus. There, she makes it ecstatically clear that the good feeling comes from – what else? – love. Avicii, in his interpolation of the sample, withholds this ecstatic resolution by literally cutting it out of the sample. . The overwhelming affect of “Levels” is inconclusive sadness, chronic aimlessness. It feels “infinite,” invoking a parameter of what has historically constituted the sublime in the form of immutable beauty while highlighting the whole configuration’s morose undertones – it could be a paean to the unquenchable thirst of the death drive. The music video, of course, depicts the desperate excitement of disrupting the endless routine of work – you cannot choose the world you are born into but sometimes you can dance to energetic music and temporarily forget certain things.

But these days, it seems fewer and fewer people can even muster the mental energy necessary for partying. Mark Fisher has written that “Partying is a job … in conditions of objective immiseration and economic downturn, making up the affective deficit is outsourced to us.”15 Unlike most jobs, though, rolling face with all of your closest friends can at least create the illusion of meaning. In her essay about the Zac Efron-starring EDM film We Are Your Friends, Ayesha Siddiqi argues that its depictions of partying were particularly powerful, demonstrating the sacred value of recreation, pleasure, and friendship in western capitalism, and the ways in which their value is fundamentally constituted by their function as a reprieve from the pressures of simply existing.16 Today, these pressures permeate the party-sphere’s porous edge. From Future and Gunna to Spotify-primed corporate indie, anhedonia and the exhaustion of the capacity to feel pleasure are some of the foremost overarching themes of today’s popular music.17 It takes far less energy to say “mood” than it does “peace, love, energy, respect.”

In the aftermath of the crash, individuals were moved to seek out one another in semi-public spaces and form tangible social bonds. The possibility of grounding and shaping one’s conception of the world through a sense of “real” communal relation became urgently desirable in the wake of collapse. The early 2010s saw numerous attempts to escape the alienation of financialization through social reconnection and collective, embodied presence. The popularity of music festivals in general skyrocketed during this phase of the experience economy, and Burning Man transformed in the popular imagination from a relatively fringe enterprise to an unmissable experience that could very well change a relative or coworker’s life. Along these lines, EDM festivals such as the Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas could be conceived of as a mirror-image of the Occupy Wall Street Movement which loomed large in culture and politics in the early 2010s and initially began in response to the crash. Both spaces have the function of offering masses of people the opportunity to deal with the affective shortages inflicted by financialized processes of extraction; they can be seen as an opportunity to effectively reshape ones’ own “cognitive territory,” as theorist Patricia Reed might call it.18 According to Reed, battles in recent decades over the good life as an apparatus of social cohesion are waged less in hopes of territorial expansion and more in relation to the occupation of this “cognitive territory”–located in the realm of noopolitics, soft power, and control of information networks. The crowd at EDC, like Occupy, implicitly aims to establish a site-specific locality in an attempt to fight or at least ward off the effects of financial abstraction on the level of the immediately, supposedly less-technologically-mediated social. The buzz of mega-festivals seems to have normalized and worn off a bit in the intervening years. Meanwhile, underground raves today arguably synthesize certain aspects of rave’s utopianism with an insistence on the importance of in-person social bonds, but they are generally designed for more self-selecting audiences seeking basic forms of emotional and psychic sustenance, rather than otherworldly ecstasy. Where Occupy was largely a collective gesture of refusal based in leftist political analyses which specifically draw power from their historicity, EDC was markedly less concerned with its figuration in the grand narrative of humanity. Interestingly enough, both EDC and Occupy placed tremendous investment in the actualizing potential of living in the here and now. Yet EDC was of course primarily concerned with “fun,” whatever that word means: the most unstable and easily extinguishable pleasures were the most sought-after. In the right conditions, a DJ set could feel like a metanarrative in itself.

EDM utilizes a host of tools foundational to the contemporary military industrial complex, borrowing techniques from both sonic warfare and more abstract forms of cognitive-physiological territorialization. As Friedrich Kittler once claimed of rock and roll, EDM “is a misuse of military equipment.”19 The canonical era of rock and roll was enabled by machines originally designed for “tank divisions, bomber squadrons, and packs of U-boats.” Looking to the future, Kittler argued that “music made of binary codes” would be a “misuse of military equipment from World War N+1.” And so it has come to pass; the military’s longstanding development of computational technologies has led us to house, techno, and of course, EDM. For example, U.K. hardcore duo 2 Bad Mice’s 1992 hit “Bombscare” is assembled through digital production techniques from a spartan selection of breakbeats, joyously demented synths, and a literal bomb sample. In terms of both technical process and phonic substance, the song provokes reflection on the etymology of dance music’s fabled “drop.” EDM, by nature, needs its drops, which in both their formal sonic character and coercive tactility resemble nothing so much as the explosions of warfare.20 Relatedly, “The Disco” was also specifically utilized a weapon in the arsenal of the United States’ “war on terror”: it was the informal name US troops gave to a sonic torture room in Mosul, where captives were subjected to unspeakably loud barrage of Western popular music, from Britney Spears to Metallica. “The Disco” could be found in any region touched by the post-9/11 military campaign: torture music was also used in Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and other locations associated with the war on terror. Artist Tony Cokes’ video work Evil.16 (Torture.Musik) (2009-11) documents this particular regime of sonic warfare – at one point it declares, “Disco isn’t dead. It has gone to war.”

Tony Cokes, Evil.16 (Torture Musik), 2009–2011 (video still). Courtesy the artist; Greene Naftali, New York; Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles; and Electronic Arts Intermix, New York.

Military and police forces have long used sound as a form of violent crowd control: sound bombs have been deployed against Palestinian civilians in Gaza much like LRAD (Long Range Acoustic Device) sound cannons were deployed against protestors in Ferguson and at the Dakota Access Pipeline protest. The deployment of extreme sound is a tried and true way of regulating environments through sensory domination: techniques of sonic warfare only work if they cannot be ignored, if their contagiousness is undeniable. Similarly, EDM does not function properly unless its effect is total and all-encompassing–regardless of whether a given song is advocating a “positive” feeling. It is telling that Australian EDM duo Knife Party released a wildly successful singled literally called “LRAD” in 2013. Producing effective tracks in the genre requires a great deal of technical precision in order to unequivocally sway not only the emotions but the physical bodies of a homogenized crowd: there are concrete targets artists need to hit if they want to make a successful track.21 Meditating upon the connections between militarization and club music, it’s impossible not to think of hugely influential Detroit techno collective Underground Resistance, whose militarized vision of Black self-determination advocates revolution through electronic sound. Despite being fundamentally indebted to the sonic innovations of UR, EDM ostensibly construes itself as apolitical, rejecting the group's explicitly countercultural call to "join the resistance and combat the mediocre audio and visual programming that is being fed to the inhabitants of earth."

Writer and musician DeForrest Brown Jr. has shown that techno in its original formulation during the 80s was borne out of an entanglement with an emergent managerial class: the technocrats. The new information technology systems setting post-Fordism into motion were too complex for workers to understand, it was posited, so the divide between "skilled" and "unskilled" labor was to be reified along racial and economic lines. From a technocratic point of view, the populace was an optimizable tool that should be fine-tuned and pushed around in service of overall system performance – in other words, society was ripe for debugging. In post-industrial Detroit, techno was being made with the new kinds of digital tools through which technocracy exerted its control – synthesizers and drum machines finally available for consumer purchase after years of seclusion in universities and military R&D facilities – and yet it also sought to escape that control's grip and pursue independence. Decades later, EDM adopts many of techno's formal characteristics, but its commitment to white, upwardly-mobile markets results in a disavowal of its musical precedents’ historical context. EDM’s relationship to financial capitalism’s technocratic class is certainly less ambivalent than techno’s. And so, it is unsurprising to hear the genre at a luxury gym or a WeWork. The music is undeniably effective at helping listeners relieve the pressures of life in hell, and yet it also has no reservations singing the melodies of financialized technocracy like a siren on a cliff. EDM’s contextual adaptability arises from the fact that it is truly organic to the networked experience economy: just like a thumbs-up on Facebook, it is able to generate predictable and intense allotments of sensation in a profoundly wide range of contexts despite – and perhaps because of – its rigid formal constraints. Indeed, while it can be said that audiences always 'complete' pieces of music by listening to them, the genre stands out for feeling just a little more incomplete than others.

Is EDM more of a disavowal of the realities of life under financial capitalism or a way of describing it as literally as possible, regardless of the producers’ intentions? Can the technologies of financial speculation that so violently shape the present be repurposed in any meaningfully useful way? At the end of the day, EDM is a bit like a scab on the mottled flesh of the social body. When you pick it off and inspect it up close, the wound underneath isn’t so fun to behold. And yet, precisely because of its relative unlistenability, EDM can tell us things we are not particularly eager to hear. The genre’s messages are strangely encrypted: behind each lyric that barely passes a Turing test, there are messages to decode, especially when an entire music festival is compelled to sing along. If you applied 30,000 rounds of digital distortion to Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto,” transformed the PDF into midi and plugged the result into Garageband, the genre is probably what you’d hear. Certain styles of music reward contemplation because they suggest rich new worlds of sonic possibility – the sounds actively seek to adjust the shape of things to come – and, by contrast, EDM is frighteningly interesting for how at home it is in the ouroboros of financial logic. It is certainly more interesting to spend extended periods of time with than a lot of “experimental” music purporting to engage with related themes. As time goes on, this scab is starting to melt into a scar, and every scar has a story.

1. Free indirect style has its appeal. W.G. Sebald has said that in past centuries it made sense for fiction writers to employ omniscient narration, but that this is no longer the case. One cannot “be a narrator who knows what the rules are and who knows the answers to certain questions.” He explains: “I think these certainties have been taken away from us by the course of history, and that we do have to acknowledge our own sense of ignorance and of insufficiency in these matters and therefore to try and write accordingly.” James Wood, How Fiction Works.

2. Fred Moten, In The Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, 2003, University of Minessota Press.

3. Costas Lapavitsas, Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All . P. 32.

4. I want to make clear that I am not presenting Malik’s argument as the definitive account of finance and financiality. For me, his is one amongst other possible theories, and the premise of his argument is obviously extremely debatable. Nonetheless, I find it provocative and compelling, and particularly resonant with the set of concerns I explore in this essay.

5. Suhail Malik, “The Ontology of Finance,” p. 785, p. 723. Collapse Volume VIII.

6. Patricia Reed, “Optimist Realism: Finance and the Politicization of Anticipation.” MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype. P. 19. Sociologist Elena Esposito, who is heavily cited in Malik’s work, has offered the following: “If the future is made up of the combination and interchange between present future [how the future looks from the present] and future present [how the present looks from the future], then the market of derivatives can be seen as a great apparatus for the production of the future.” Elena Esposito, The Future of Futures: The Time of Money in Financing and Society. P. 127.

7. Suhail Malik citing Esposito in “The Speculative Time-Complex,” written with Armen Avanessian. DIS.

8. Joshua Clover, 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This to Sing About. P. 70.

9. Ian Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic. p. 71, p. 139

10. Anna Codrea-Rado, “How Do We Stop Drug Deaths At Festivals?” Noisey. Harley Brown, “Festival Deaths on the Rise in the EDM World.” Billboard.

11. Rong-Gong Lin II, “After a summer of deaths, popular Halloween rave won't be held.” Los Angeles Times.

12. Google search for “alexander iadarola drug death thump”: https://www.google.com/search?q=alexander+iadarola+drug+death+thump&oq=alexander+iadarola+drug+death+thump&aqs=chrome..69i57.3252j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

13. Claire Lobenfeld, “EDM star Kaskade speaks out on drug-related deaths: “This is not unique to dance music.” FACT.

14. Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. P. 292

15. Ayesha Siddiqi, “Our Brand Could Be Your Crisis.” The New Inquiry.

16. See Simone White, METRO BOOMIN WANT SOME MORE N*GGA Pp. 10-11

17. Patrica Reed. “Economies of Common Infinitude.” Intangible Economies. P. 183.

18. Friedrich Kittler, The Truth of the Technological World. “Rock Music: A Misuse of Military Equipment.” Pp. 152-164.

19. For more, see Steve Goodman aka Kode9’s 2012 book Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear.

20. Moustafa Bayoumi, “Disco Inferno.” The Nation.

21. Luis-Manuel Garcia, “Beats, flesh, and grain: sonic tactility and affect in electronic dance music.” Sound Studies. Nino Auricchio, “Natural Highs: Timbre and Chills in Electronic Dance Music.” Popular Music Studies Today.

22. Sleevenotes for Revolution For Change, released 1992 on Network Records.

23. DeForrest Brown Jr. “Techno is technocracy.” FACT.