The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Levels and Bosses, Preliminary Trailer 01, 2017-18. Video of virtual environment; music by Molly Joyce.

Emer Grant: There are several different formats to your practice, realized across the Levels and Bosses project; at what level do we enter into your work? Does it start from the screen, or the gallery, or from the pages on the graphic novel? What do you see as the relationship between the paintings, the drawings, and the virtual reality game? Is it about being in real-time, or about realism? I’m also thinking about the boss and level metaphor. Do concepts of ranks and levels serve as references to traditional hierarchies across industrialization?

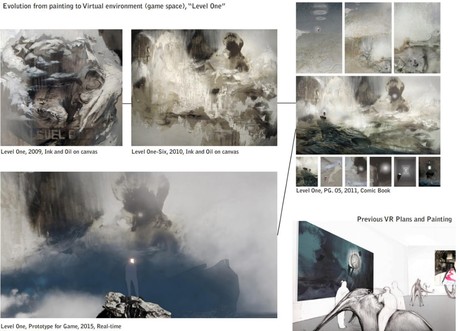

Leo Castaneda: The graphic novel is a good place to start. It is a good segue into painting and what I’m doing now, which is translating the graphic novel into a fully realized videogame. It started with a challenge from a college friend of mine, Victor Ochoa, who established a comic book anthology back in 2011; he knew my work and suggested I created a comic book out of the “Level One” paintings. The Levels and Bosses series started in 2009 as an attempt to create a mythology out of randomness by adopting the structure of videogaming. There was something about the imagery in the newer games that was unnerving, and this sentiment moved into the aesthetics of my work. In games, each level has a “boss” that would be an antagonist or gatekeeper at the end of the level to allow you to progress to the next level. It’s a matter of progressing through killing or destroying the gatekeeper. Importing this structure would allow me to have the image freedom of working between abstraction and representation, and also have fun creating characters and worlds.

The Level One painting was created through thinking of interactions with the environment in early games. Traditionally, player characters explored levels. The programmer would decide if a pixel was interactive or not; liquids, gases, and solids were interchangeable depending on what they chose as the principle (or what gaming programs call “collision”). I chose to paint an epic version of this using a muted color palette, one stemming from and related to explosive sci-fi Hollywood blockbusters. The graphic novel took ten paintings that I had done exploring the “Level One” I’d created, and its subdivisions (Level 1-1, 1-2, etc.), a reference to how levels are divided in games. In creating the graphic novel, I got to imagine space between the level paintings. It was like creating a map out of destinations. Through structuring the visuals, I could in turn initiate a story.

Level One, Graphic Novel, 2011, page 6.

Level One, Graphic Novel, 2011, page 6.

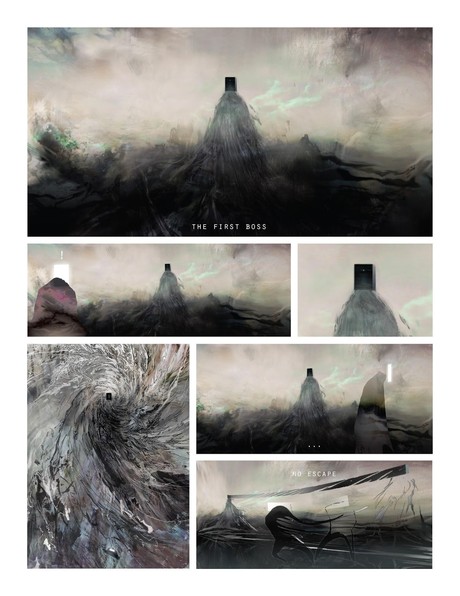

I tried to consolidate the narrative in creating the First Boss, a cube abstract figure. A sentient black hole – from which the entirety of “Level One” emerges – was rendered by a happy accident of a damaged monoprinting plate. When I was trying to create the protagonist, I wanted there to be less of the traditional narrative binary between protagonist and boss. I decided to call this protagonist “The Other”; the letter “O” relates to the number 0 (zero), a precursor to the 1 of the boss.

The work’s range and ambition has taken on different characteristics throughout its evolution. I eventually realized that the culmination of the work should be an actual videogame. A videogame that innately deconstructs and expands what a videogame is and can be. The process within my painting has become more of a feedback loop: the paintings are created out of images of virtual spaces, and get re-inserted into the virtual. Some paintings work as textures that inform the virtual environment, and other become translations of it.

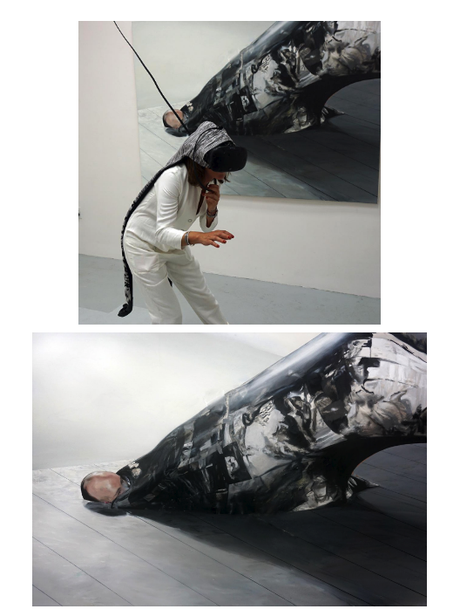

Item 93201 with Image of Boss, 2014. Virtual reality sculpture/machine: Computer, VR headset, fiberglass, wood, plastic, fabric. Painting: Acrylic Canvas, Wood, faux leather, projector handles. Sculpture: 10ftx5ftx5ft. Painting: 7x11x2ft.

Item Showroom, 2016-17. Virtual Reality environment and video.

EG: Could you talk a bit more about the relationship of frame and “otherness”; I’m interested in how you might clarify what sociological perspective you are referring to. Are you referring specifically to racial, class, and gendered connotations of “the Other” with the black box? Whose other? Also, do you problematize narrative here in the context of “otherness,” in which master narratives and “otherness” offer a dialectical positionality?

LC: The game addresses controlling a thing, a something, that is explicitly not your own body. Videogames are often segmented into first- and third-person perspectives. The frame here is the point of view; a central idea of the game is a possibility of switching, meaning, the potential shift in the relationship between protagonist and antagonist. The player character at the beginning is a humanoid figure, seen in third person view, a genderless, posthuman, ethnically ambiguous cyborg who explores ambiguous landscapes and encounters various “bosses” that challenge perceptions about boundaries and roles in games. In most videogames, you generally work through a linear progression, starting at point zero and chronologically moving through the game by winning, traversing entities, killing them, taking their essence, for the sake of climbing. There is no specific awareness and it's also very binary, very antagonistic. I wanted to challenge that.

Levels and Bosses: Level One interior, “in-game” still, 2017-18.

EG: How do you address the contrast between pleasure and leisure and rules as architecture in drafting videogames as a critical medium?

LC: I'm aware that whatever is pleasurable to me is also a construct of societal conditions. Going back and analyzing my choices involves breaking down decisions into distinctions, which is intrinsic to my methodology. What basically happens in the graphic novel, is that from the point of creation (represented by an explosion), there is the gravitational, coordinated, and choreographed journey between the self and other that flips between boss and protagonist. The perspective feels like it is always pending, in hold, about to change.

EG: The explosive scene reminds me of the mutation scene in Akira; the character Tetsuo loses control of his powers and transforms into a giant human amoeba that consumes everything it touches. You are spared no mercy in terms of visual affect and effect. From that point on, it is relentless. I see the reference to anime as a stylistic choice in your work. Anime references can be problematic because of their heteronormative undertones; they are frequently criticized for darker fetishistic tendencies. If you are in fact referring to fantasy animation as a stylistic choice, what kind of value do you extract from it?

LC: Plenty of anime is an inspiration for the work. I think of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and even Dragon Ball Z, using these titles as a jumping off point for the development of a more critical framework. Take the cycles of power in Dragon Ball Z. In my mind, they resemble how I see capitalism functioning at the moment, in which one character’s power level endlessly increases, and likewise, the strength of the enemies increases, both to a point so exponential that their purpose ceases to matter.

As a piece bridging gaming and art, it was important to me to focus or to create the aesthetic of spectacle that draws gamers in. Audiences are already more familiar with games industries, or the movie industry as cultural gateways. I'm happy for people to enter into my work through spectacle and while they're there, differentiate between the imagined and traditional roles of bosses and environments, and in this tension, find ways of creating meaning.

For instance, in my game, I started to play with the idea of an exponential and unbalanced power dynamic between characters, such that each violence and defeat are choices made by both parties. Throughout Levels and Bosses, the Other’s engagement with each boss reimagines relationships of contact between players and antagonists.

In this space, I wanted to allow for a moment of vulnerability, in which the boss would just be still. It would be a matter of continually striking until the protagonist realized that a different approach was needed, one that involved contact. There is a sense of being reprimanded. So, at one stage, a character makes the realization and is teleported, but their insight still would lead to some sort of damage. These wounds accumulate from traveling through the game. The game has a specific fictionalization of violence in this metaphorical wounding. Contact really comes in the moment when you're given the choice to hit or touch the boss; contact is the in-between. Rather than defeating someone to attain victory, the goal is more progression through contact. We expand through these choices to hit or to touch, and progress through each choice made.

EG: Is this work intended for one person to experience at a time? Or is there a community that can emerge, a utopian gesture from audiences participating in the piece, and if so, how to you express this as a strategy in art? There are many possible stages of the piece in an exhibition, but could you talk about the ideal stagings, which create the community you suggest the work imagines?

LC: Exhibitioning involves multiple angles. If I'm thinking about an imaginary audience I guess it would be people who can relate to my understanding of videogames as possessing multiple layers of meaning. The primary platform for this work is Steam, where a lot of videogames get hosted. With at least 125 million users on the site, you can find artistic or independent videogames are either free, or distributing between 1000 and 1 million copies globally for $5 -$10. Gamers come in a whole range of ages and socio-economic backgrounds. It is interesting; most of the people who make videogames are white males but many of the people who play videogames come from all different types of ethnic groups.

EG: I wonder if that dynamic – white men making games for non-white players, if we simplify it – is possibly an iteration of colonialism, but in new form? Ethics and representation come into play in creating narrative, especially when interactivity is a dominant axis. How you see your works as providing an alternative to the industry standard?

LC: Yes, this is an iteration of colonization. I think about this often. The gaming industry is ripe with decision makers in positions of power who ultimately get to decide the validity of narratives and which stories matter. In addition to the ways in which this affects representation, there’s the example of the recent purchase of the Star Wars IP: Disney has disowned whole subsections of previously made stories, such as the animated Clone Wars, as out of canon. Fan-created content isn’t even taken into consideration; the company has hard copyright hounds that stifle community participation. People love to draw fanart and fantasize about their interpretation of gaming and movie characters, and for my game I am thinking about the possibility of future user-generated content for players to be able to add their own levels to this game, even with financial retribution. The game establishes a master narrative out of randomness, frames it as rather arbitrary, and then makes it flexible for communal re-interpretation and change, an oscillating flip and reversal of the colonization of the narrative.

Item with oVerhead Reality, 2016. Virtual reality sculpture/accessory: headset, fabric, controllers; interior virtual environment made through videogame software. 10x10x48 inches. Human interacting - Variable. Painting: Item Showroom Screenshot #143

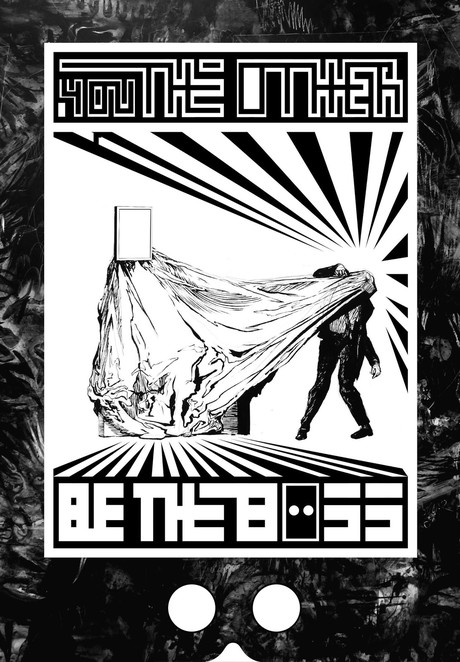

Poster for Entering Virtual Reality Machine, 2013.

EG: How do you see artistic production changing, in terms of collaboration, collective labor, given the increasing complexity of gaming, its companies, artists, designers, programmers? What can artists learn from proximity to these large, complex groups of technologically skilled professionals?

LC: Currently I'm thinking about all of this in terms of authorship because I struggle with how I use my name in this context. In the videogame industry, there is a team and a company that is behind a project. I wouldn’t want this to be known as Leo’s game; for the range of the piece, it makes sense to release it under a company alias.

I struggle because I’ve gone through all the traditional art world steps: art school, an MFA, teaching, to build my practice as an individual working artist. I have to jump through certain loopholes to just have the game present on the Steam platform. Then I think about collaboration, and how a programmer would want to work with a company. I think about working as or through a different entity, not as one that will just serve my “fame”, or notoriety, as an artist.

The other side of this is my identity as a Latin American artist and the voice in the work that is created culturally. My background and upbringing appears in my choices. I consider the reception of a company in the art world, versus the reception of an individual. It’s interesting now, as across the art world we are seeing the system of credit emerging, in which everyone’s work or labor is somehow acknowledged as part of the creative process. And I wonder if operating as a company open this system up beyond mere gestures. For now I’ve played it safe as an individual in the studio.

EG: You’re creating an environment where people engage through initiating endless possibilities. This is a philosophical manifestation of the virtual, through the virtual. It’s a way to stage possibility, even, and offer a model that can be replicated. And you also refer to painting as a thinking process which translates as a strategy across industries. It seems these methods – creating an environment in which possibility multiplies and the audience has agency, or using painting to work across audiences – is a type of a speculative proposition, for renewed participation.

LC: In the gaming and movie industries, painting and drawing are used to create “concept art” as the visual plan towards the creation of worlds and characters. This is usually a team effort towards finding a coherent narrative, and as mentioned before doesn’t leave room for audience input. In my work I try to use the strategies of “concept art” to arrange randomness and thus allow multiple viewpoints to merge through sequencing and proximity. If the possibility of audience participation can add to those narrative nodes of randomness, I hope the work in the end is an empowering or hopeful proposition.

Questionnaire

Age: 29

Location: Miami, FL

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

Actively, 2013, and indirectly 2009 through the concepts; back to middle school through interests.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

Cooper Union for BFA and Hunter College for MFA, both for Studio Art.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

Art practice plus teaching 3D animation and drawing at Florida International University this year as a visiting instructor.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)