This text accompanies the presentation of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s Samsung as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’s website is simply a list of their works centered on the page ordered in no obvious way. This format in concert with the standard black text and blue hyperlink color scheme harkens back to Web 1.0. The design choice—and the exclusive use of the artist duo’s signature Monaco font—suggests a web presence that has not seen an overhaul since its inception. Perhaps the intention is to affect unresponsiveness; although the site itself is mobile-friendly, most links will not load outside a desktop browser, and the catalogue of works under “M0BILE DEVICE: CLICK HERE” is noticeably incomplete.

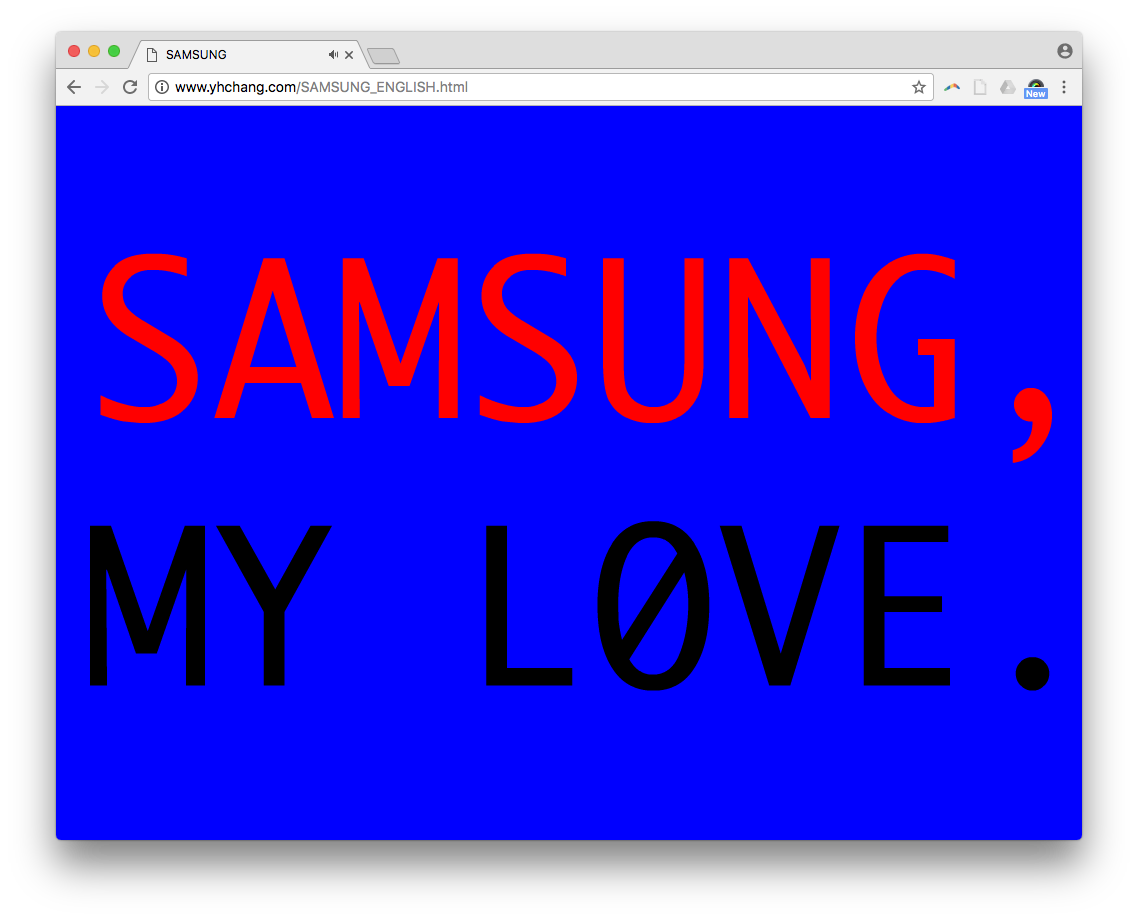

Samsung is the seventh work listed and available in five languages (set to jazz), as well as an additional English version set to tango. The piece loads almost instantaneously, opening with a flash of the Samsung corporation’s trademark blue fleeting enough to be read as a glitch. The screen transitions into a countdown that fills the browser window crisply at any size, a feature of the artists’ preferred format of Flash animation.

“ABOUT MY WORK AND MYSELF AND ALL THE REST I USED TO SAY:/,” the narrator begins, “I HAVE NOTHING TO SAY AND I’M SAYING IT:.”

The narrator is perhaps an anonymous South Korean citizen, perhaps a “hoesawon,” one of the legions of company workers that pack the nation’s offices. Or perhaps it is YHCHI themselves. The narrator concedes no introduction to the viewer, instead only proffering the abstracted drudgery of their existence.

The speed of the text is tightly synced to the music, oftentimes bordering on illegibility as the words pass too quickly to comfortably read. The viewer is kept in a state of tension as the ambiance of the corporate lobby music stands at odds with the need for constant attention to the screen.

While interactivity is considered a hallmark of net art, YHCHI’s work—Samsung included—rejects it entirely, lacking in hyperlinks and denying the visitor the ability to pause or scrub. The duration of any given piece is a mystery. The visitor is a passive recipient, much like a movie theater goer, an allusion encouraged by the use of a film leader at the beginning of many works.

“FINALLY I HAVE AN IDEA:/SAMSUNG.”

“SAMSUNG,/MY COUNTRY’S SAVIOR”

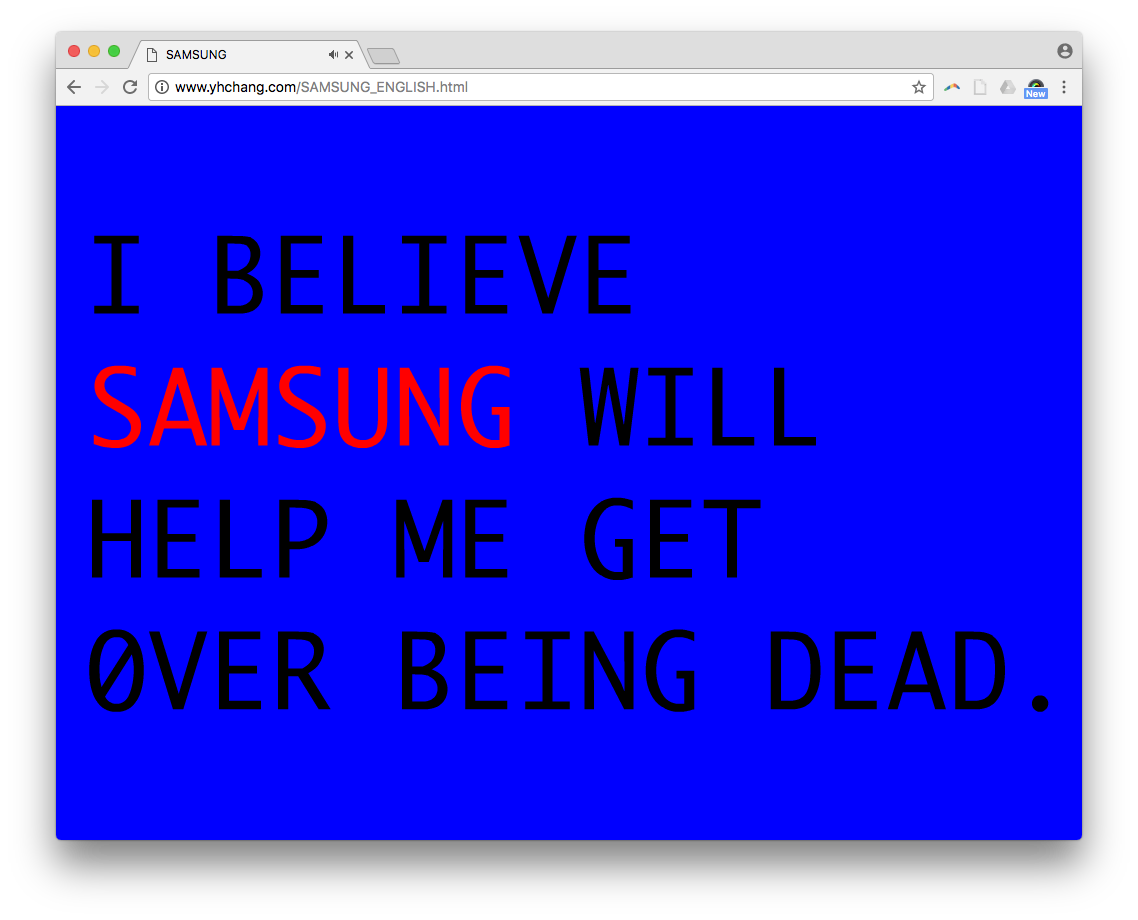

“I BELIEVE/SAMSUNG WILL/HELP ME GET/OVER BEING DEAD.”

The work begins to seem less like film and more like advertising as the screen flashes with frame after frame of the conglomerate’s name, reminiscent of the jumbotron-lined streets of Seoul. Most of the piece features black text on a blue background, with the sole exception of the word “SAMSUNG,” which is written in red. The contrast leaves an afterimage, a lingering that attests to Samsung’s pervasiveness, in the retina and in the public consciousness of South Korea.

YHCHI has said that they “would like [their] work to exert a dictatorial stranglehold on the reader.” Inundation is just one of several tactics employed by YHCHI that seems borrowed from corporate stratagems. The cheeky tone of Samsung could be interpreted as critique, but YHCHI’s self-identification with corporate aesthetics may stem from a genuine desire to participate in its mechanisms, even as, by virtue of the corporation Samsung’s ubiquity in South Korea, participation is compulsory. To interpret Samsung as a unilateral criticism of the corporation Samsung is to ignore the complexity of South Korea’s relationship to its conglomerates.

YHCHI made Samsung in 1999, two short years after the 1997 IMF crisis decimated the South Korean economy and set the stage for Samsung’s eventual monopolization of the global telecommunication sector. In 1995, South Korea had responded to international pressure to open up its economy by adopting the “segyehwa” globalization policy. The degree of damage wrought by the IMF crisis can largely be attributed to profligate corporate borrowing, as South Korea’s “chaebol” conglomerates aggressively expanded to compete in the new global market.

To save the economy from complete collapse, South Korea accepted a $60 billion bailout package from the IMF, the terms of which slashed excess production capacity, leading to the shuttering of fourteen of the nation’s largest industrial conglomerates. Samsung not only survived the sweep with minimal losses but emerged poised to lead the shift in national focus to the ICT (Information and Communications Technology) industry in a landscape stripped of domestic competitors.

Today, not only does Samsung account for around 20% of South Korea’s exports, it also figures prominently in Korean national identity. Some Koreans go so far as to call their country “the Republic of Samsung.” The moniker is deserved, for Samsung’s influence extends far beyond its products (already omnipresent in South Korean daily life) into the nation’s government, press, media, and culture. Samsung has withstood multiple corruption charges due to direct government intervention, as in the pardoning of Samsung Chairman Lee Kun-Hee by then-President Lee Myung-bak in anticipation of South Korea’s bid for the 2018 Winter Olympics.

YHCHI’s Samsung can be read as an indictment of South Korea’s obsession with multinational conglomerates, but YHCHI has stated that the “Heavy Industries” in their name stemmed from their desire to “receive some of that love.” Young-Hae Chang refers to herself as the CEO, Mark Voge as the CIO, and YHCHI as their “company.” That YHCHI models themselves after the same corporate structures they ostensibly interrogate suggests that the artists are subject to the same tension between identification with and critique of corporations experienced by the Korean population.

According to Lee Cheol-haeng, head of the corporate policy team at the Federation of Korean Industries, “many Koreans right now have dual minds about chaebols… They say, ‘I hate chaebols, but I want my son to work for one.’” The love of which YHCHI spoke is clearly not unqualified. Instead, it arises from a potent cocktail of frustration with nepotistic and monopolistic business models, appreciation for the chaebols’ role in establishing South Korea as an economic power, and simply the inextricability of corporate products from heightened social mobility and standards of living. Not to mention, the corporation Samsung’s framing of their ruthless business practices as dedication to quality, adaptability, and constant vigilance provides a strong incentive for Koreans to personally identify with its brand narrative.

The piece Samsung addresses the complex nature of the corporation—its existence not only as an economic entity but also as an emotional phantom, reaching its incorporeal fingers into relationships, daydreams, and fantasies. The text of Samsung, demonstrating many of the formal qualities of poetry, is interspersed with conversational breaks that establish intimacy with the viewer. The tone becomes conspiratorial as the narrator asks, “CAN/I CONFIDE/IN YOU?” There is no option to decline. The viewer is rendered complicit in the narrator’s confession of their adoration of Samsung.

This tension between codependence and criticism can also be seen in YHCHI’s use of English. YHCHI writes in three languages: English, Korean, and French, with any other translations produced through outside collaborations (Samsung is presented in their three core languages, in addition to German and Spanish). Though they are often resistant to politicized interpretations of their work, YHCHI acknowledges language, and English in particular, as a “political and powerful tool.”

They explain: “The digital world, globalization, globalized culture, those who believe in Westernization and those who fight it to [the] death[,] they all rely on one constant: no, not the computer, but English and the cultural baggage inherent in English, whether you like it or not.”

Precociously sensitive to the tectonics of linguistic and geopolitical contexts online, YHCHI asserted in a 2002 interview with Thom Swiss: to participate in the web in English is to “implicitly justify a certain history.” The multiple translations of each work reveals nuanced relations within existing power structures. The individual qualities of each language as well as their varied network of interrelations—to each other, and to English specifically—are highlighted by the consistency of other formal aspects across each translated iteration of an individual work, in addition to YHCHI’s practice at large.

YHCHI’s understanding of the use of English on the web as both a universalizer and a collusion mirrors their, and South Korea’s, complicated relationship to globalization. Only recently Korea was a relatively closed country, but now, English acts as a marker of cosmopolitanism, whether plastered storefront signage or slipped in as loanwords in everyday conversation. For a nation whose interactions with foreign powers has historically been tarnished by conquest, the opportunity to be a dominant economic force is bittersweet. It seems South Korea (and by extension YHCHI) is willing to concede the playing field choice to English for the chance to participate on the global stage, in the market, and—in YHCHI’s case—on the internet.

But in the end, YHCHI’s adamant apolitical stance makes it difficult to ascertain the intent of their work. Samsung, for all its criticisms or celebrations of the corporation’s hold on its home country, suggests no solution to the Korean public’s difficult position. The artists’ irreverent assessment of the situation necessitates the question: Does YHCHI have an obligation to do more than simply present the issue? Must they propose an alternative for this work to be effective?

Or perhaps even asking betrays a Western expectation. Perhaps the capacity to understand is lost in translation. Perhaps one must be saved by an idea.

SAMSUNG.