This essay accompanies the presentation of Marisa Olson’s Marisa’s American Idol Audition Training Blog (2004-2005) as part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

MC: What was going on in your practice, and in American pop culture, when you started the blog?

MO: I did the project in 2004 and it was very early days of blogs. They were this new medium that people were excited about, and I was really always interested in autobiography and women’s narratives, which attracted me to them.

When I thought about starting one, I called my most tech-savvy artist friend to ask how to do it, which was Cory Arcangel. And he was like, “I’m really not sure, but I have this other tech-savvy friend who you should call, Jonah Peretti. Ask him.”

So I called Jonah, [now] CEO of Buzzfeed and co-founder of Huffington Post, but in 2004 he said, “I’m really not sure, but my sister, Chelsea Peretti, is a comedian in downtown New York, and she and a bunch of her friends sometimes use blogs, and I think they use something called Wordpress.” So I literally just did a Yahoo! search for Wordpress, and that’s how I figured out how to start a blog.

At the time, I had a secret addiction to American Idol. I used to sneak home from openings to watch it, and they had just raised their age limit to audition to 27, which was how old I was.

It evolved slowly, the idea of keeping a blog. It was this inside joke with friends, sort of like, “Oh, well, maybe I would audition now that I’m allowed to, but it would be as an art project, like an endurance project. And maybe I would keep a blog so all my friends would be in on the joke.” And then it was like, “Well, I would do it as this way to indulge my love of the show but also critique all of the gender norms that they’re always reinforcing.” Like when they’re telling average-weight girls that they’re too fat to be a star, or when they’re telling guys that they’re not masculine enough to be a singer, or something like that.

I started keeping all of these diary entries of quote-unquote training exercises. None of them really had to do with singing at all. All had to do with being a star, being more feminine, standing out. In the beginning of the project, I was trying to critique the relationship between fame and talent on the show.

This was the first internet project I ever did. It sent me in an entirely new direction. I was amazed by what happened with it, because of the timing of the election. So I was keeping this over the summer, and leading up to the fall.

My audition for American Idol was in October of 2004, just a few weeks before the election between Bush and Kerry. A lot of people were saying that people of our generation were not participating in elections, were not showing up to vote, and if they did it might make a difference.What was interesting to me, anyway, was that the show, the demographic for American Idol, was exactly the same as this demographic that was not participating in elections.

American Idol is predicated on this idea of “text your vote.” It was probably one of the first American shows to really use SMS. It was a novel use of texting, really. It really had this democratic premise, right?

“American idol” was the number one search term on the internet at the time, and somehow my site came up number one and their [official] site came up number three. And even though my site looks nothing like an official American Idol site, I was getting so many emails and so many hits from people who believed that my site was really the official one.

I was getting 30,000 hits a day from the same people who were not participating politically. And I was really trying to tweak the words that I was using and lure them in.

I started talking about using your voice, not just to sing, but politically. I started tweaking the posts that I was using from talking about the things that I originally described, to talking about where to register to vote. I brought voter registration forms with me to the line when I showed up to audition.

Friends of mine, family members of mine, people who knew me, who were extremely confused, because this was the first project of this nature that I had ever done. They were like, “Is this real, or is this a parody?” And my answer was just, “Yes.”

But yes, I really did show up to audition, which is a very different process in reality than what they show on TV. They make you sign more and more contracts with each round, saying that you will not reveal what the real process is.

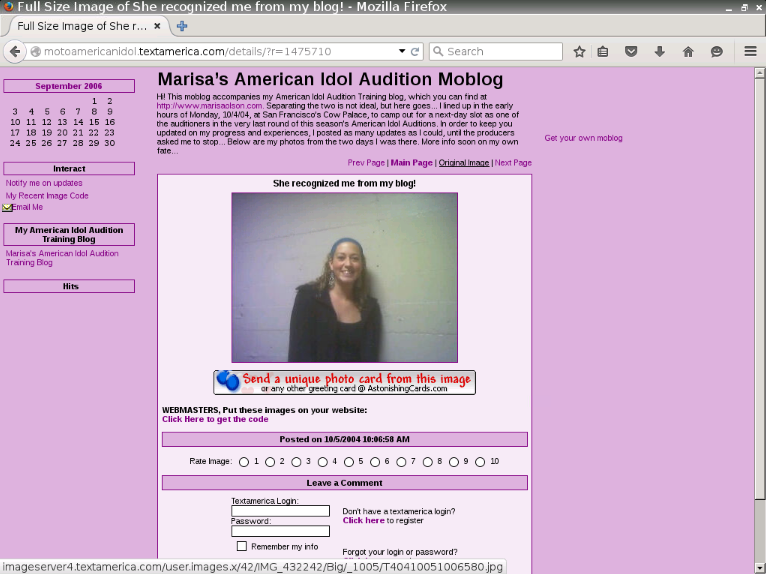

I had a secondary blog, a moblog, which was a short-lived genre, that I linked to on my blog, where I was taking behind-the-scenes mobile photos and uploading them. But I could only do that for so long before they caught on to me and cut me off.

At this time in particular, I was really interested in the voice and the voice as a double entendre, the singing voice but also the political voice, and how artists get disenfranchised and cut off from their voice because the show really takes aways artists’ rights. There were a lot of stories about how if you made it onto the show they took away your royalties, they took away your right to craft and own your own identity and persona. They took away a lot of things from you, but people were willing to do it because they wanted so much to be famous. I wanted to expose some of that.

I always feel like this was the project that really made me an artist, and in a way it was really working on the internet that allowed me to do this, too.

It wasn’t even that long after I had finished my undergrad in 2000 with an honors thesis on the semiotics of digital storytelling, which is such a nerdy topic. I was looking at the use of digital media in autobiographies, and then there I was doing this autobiographical project using new media. So it was just close to my nerdy home.

But I had gone to Goldsmiths and had a disenchanting experience there, working mostly on large-scale sculptural and installation work. Even though I was Rhizome’s first paid writer in the late ‘90s, and was writing about new media and curating in new media and knew a lot about it, I hadn’t actually made any new media artwork myself up until 2004.

So this was my first experience putting my money where my mouth was and making new media. And it was amazing having this instant feedback experience of making a post in the morning, having people comment on it, having a live feedback experience. It was just amazing. It sent me off in new direction, and showed me that this was really what I wanted to do.

MC: What sort of reception did the blog get? Did you get a lot of comments and emails?

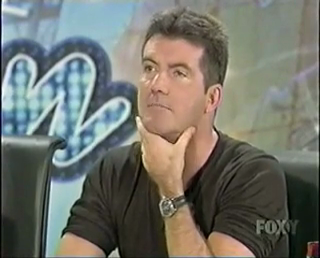

I felt as if some of the comments on my Idol blog were quite snarky, very Simon Cowell in tone. I had this theory going that comments of the proto-millennial tone were very influenced by Simon Cowell.

There was this one guy, you might see his comments on the blog because I even started posting about him. He was really criticizing me and my song choices and my outfit choices and stuff. He was very, very verbal on the blog, and then he made himself stand out at the audition as well, but then it turned out that he couldn’t sing at all. It was really funny.

Sometimes I would get really sad ones. I’ve had people write me and be like, “Oh, my mom loves my sister more than me and I feel like if I get on this show she’ll pay attention to me.” Or I’ve gotten ones with pictures... a girl sent me a picture of herself and she was like, “I’m really overweight and I want to get on the show, so that kids will be nicer to me.” Just really sad stuff.

Marisa Olson, The One That Got Away, 2005, video still

MC: Did it circulate on the blogosphere? I feel like there were a lot of independent blogs back then that were sort of aware of each other’s activity.

MO: Not in quite as romantic a way, as you describe, or as you might think. There was still this dynamic happening where “traditional” media and blogs were trying to sniff each other out. The New York Times wrote about the project. Not in the art section, but in the Circuits section, the tech section.

However many years later now, my family unfortunately still thinks that I’m crazy. I went to a family reunion with that New York Times article... I wasn’t in the habit of showing them every single article or whatever that I ever got, but I went to a family reunion with it because it was like, “Oh, yay, I’m in the New York Times. I’m a legit artist.” And they just read the one blog post that they referenced about me trying to get a California look by going to a tanning salon and getting a full-body rash, and they were like, “What are you doing to yourself? You’re insane. You’re...what are you doing? You’re nuts.”

I’m just saying, families don’t always understand performance art.

MC: At least you had your fans! But didn’t the project circulate in online media as well?

MO: This is an age-old story about media, but oftentimes media can become a self-fulfilling cycle. On the one hand there’s journalism for the sake of telling good story and sniffing out the news, but on the other there is media that digests itself: “Oh, a story was reported today, now we’re reporting on this story reporting on this story.” And things just reblog each other and that sort of thing.

Yahoo! was a more popular search engine than Google at the time, and American Idol was the most popular search term on Yahoo! So then my site was a Yahoo! “site of the day,” and it become a self-fulfilling prophecy type of situation. So then other blogs were writing about that, because then they wanted to be on Yahoo!’s radar. But then when Yahoo! wrote about it, then MSNBC wrote about it, and then other blogs were reblogging that, and it just became viral. It snowballed and snowballed and snowballed.

But this was pre-Jonah Peretti era—it was The Laughing Squid-era, Boing Boing-era, early blog days. People were writing about it, but it wasn’t Tumblr-era, it wasn’t even really like 4Chan and FFFFOUND!-era, [so it was a different kind of internet media cycle.]

MC: It was much more disconnected I guess.

MO: It wasn’t even so much 2.0-era yet.

MC: I like the spareness of the format you used for the project—the way you posted audio instead of video, and only .WAV files.

MO: I am a technological minimalist, and I am into the romance of democratic media. And I have also just always been a starving artist. It’s like, I’m going out and getting whatever simple tools are available to me and then transmitting them in whatever simple WSYIWYG democratic platforms are available to me. That’s how they’re going to be accessible to other people as well, you know?

MC: And then you had the second blog, the moblog, where you posted updates from the audition process itself using your cell phone.

MO: Yes.

MC: But you were sharing material about the audition process on TV, and the show was not happy about that.

MO: They were like, “Okay, no more photos now. You’ve got to put it away.”

MC: And did you take it down? Is it gone now?

MO: Oh, I don’t know. I haven’t even tried to look. Did you try to look?

[The interviewer checks. The moblog is down.]

MO: I got rejected from the show and they didn’t air any of my footage. I think part of it was because they’d realized that I was doing this to critique, that they read about it in the news.

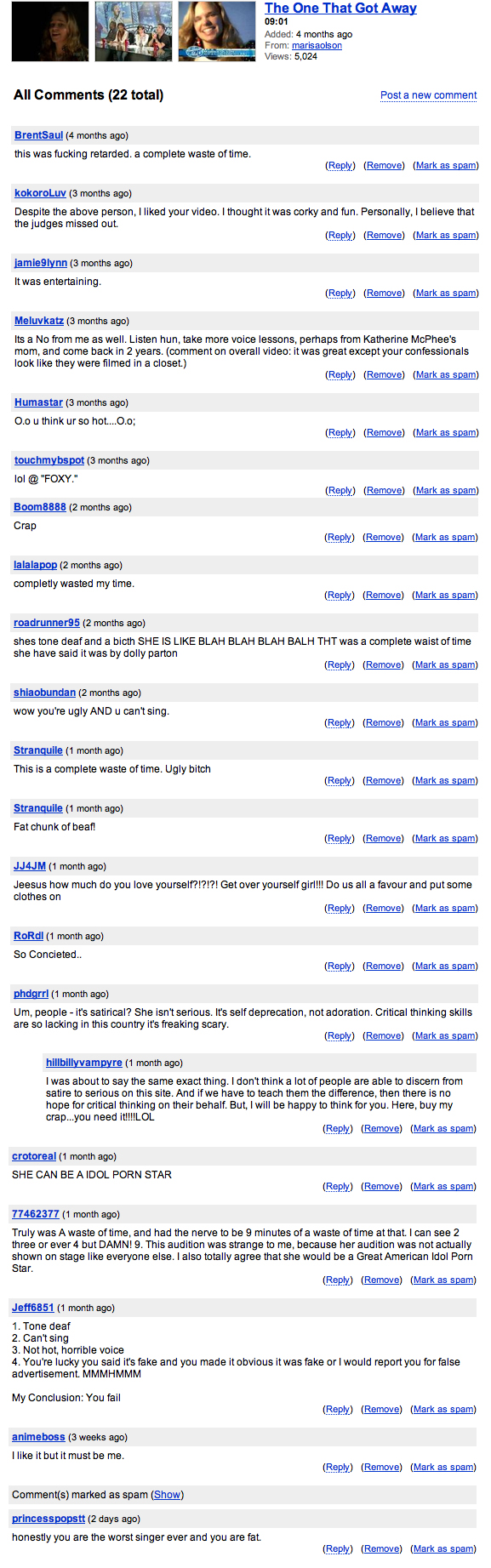

Then I made a video that was a fictional re-enactment of the show, which I can send you a link to, it’s on Vimeo. It was on YouTube for quite a while and got tens of thousands of views and had many, many comments, some of which I screen-capped and posted it on Nasty Nets at one point. But then it got taken down from YouTube for copyright violation and then I later took down my entire YouTube account because they were censoring a number of my videos.

.JPG posted to the Nasty Nets surf club by Marisa Olson

I definitely feel like, looking back on a number of net art projects I’ve done, I wish that I had some person from the future tell me like, “Hey, archiving is a thing,” had told me that things were going to disappear from the internet.

MC: But the project does still have a life—through the blog, which is still online, through the video, which also shows in gallery exhibitions, and through its place in the conversation about internet fame and online performance.

MO: Well, Sarah Cook has shown that video quite a bit and talked about it, and it’s shown a lot. That video has shown a lot. The blog used to show a lot and now the video shows more than the blog.

When I talk about it people will say, “Is it really the right way to address activism?” And I’ll just say, “Well, some young people are really turned off by [political discourse].” This is changing more lately with Trump, but sometimes I’ll say, “Young people are intimidated by activism or they’re turned off by it.” And they’re either overwhelmed by it or they don’t know how to engage. But then they know how to engage on the internet, they know how to engage in pop culture, so this is a point of entry. I’m trying to reach them where they live, and I’m always interested in that. The politics of participating in pop culture.

People were really reaching out to me, even now, years later there’s a cycle. When the auditions kick up again people write me. Certain times of year people write me again and they’ll ask me, “Do you know where the auditions are going to be?” Or, “Do you know how I can stand out at the auditions?” I can’t even reply to all the emails.