Alexei Shulgin's pioneering works in internet art are collected on his site easylife.org, but many of the links there are empty or obsolete; one called Insanity Notification sends visitors to a site indicating that Shulgin went insane at an unidentified point in the past. It has been more than five years since Shulgin left the online environment to focus on the production of tangible, marketable objects. His collaboration with Aristarkh Chernyshev began in 2003, and two years later the artists founded Electroboutique a gallery-slash-gadget shop selling distorting screens and other high-tech toys. Shulgin and Chernyshev called it "Media Art 2.0," and wrote a manifesto saying the plug-and-play nature of their new work liberated them from a "media art ghetto," adding that their manipulation of familiar screen-based interfaces contained a nugget of criticality. Their work was recently featured in "Criti Pop", an exhibition at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art (along with interactive installations that Chernyshev made in collaboration with Vladislav Efimov). - Brian Droitcour

Your recent exhibition was called "CritiPop." Could you explain where this label came from, and what it means?

We spent a long time thinking about what to call the exhibition. Media Art 2.0 no longer fit. We had moved away from media art and no longer wanted to be associated with it. Eventually, we singled out the most important feature uniting the works: critical communication contained in a popular form, with shiny plastic, bright colors, primitive interactivity, a resemblance to consumer goods, glowing LED screens and so on. Thus, "CritiPop" was born. Its effect is akin to that of advertising or propaganda: vivid, universally recognizable images that conceal a subliminal message.

There is a striking amount of texts and manifestos accompanying "CritiPop." Are you concerned that the critical component of your work won't be read without them?

Almost all these texts were written in the years preceding "CritiPop," for exhibitions in our gallery. So, it was natural to include them. But basically you're right. We had to introduce the viewer to the context, because our works are easy to read on the superficial level of real-time, eye-candy effects, brightly polished plastic and impressive animation.

Moscow critics often frame the history of Russian art after perestroika around artists like Oleg Kulik and Anatoly Osmolovsky, who worked with actions and other ephemeral forms of art during the chaotic 1990s and turned to object-based practice during the relative stability of the Putin administration. Your career follows a similar trajectory. Do you think this is a fairly accurate description of what happened? Why did you abandon net.art and begin to produce objects in collaboration with Aristarkh Chernyshev?

I think there are similarities here, but also significant differences. Unlike Kulik or Osmolovsky, who always worked on the territory of institutionalized contemporary art, I was working on the internet, which in the 1990s was an open zone for experimentation. I had become disgusted with the world of museums and galleries, where I spent quite some time in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, thanks to perestroika and the boom for Soviet art. I even decided to stop being an artist for a while.

The term net.art came later. In the mid-1990s you could make art on the internet without getting stuck in a particular context. The internet itself was the context. Eventually even net.art was institutionalized. But it did not create its own economy; only JODI could survive as internet artists, thanks to the generous grant system in the Netherlands. But net.art disappeared simply because the internet developed. As soon as a large number of people obtained access to the internet, net.art became meaningless. It dissolved in the mass of blogs and platforms. You could say that net.art invented and investigated methods and technologies used in Web 2.0.

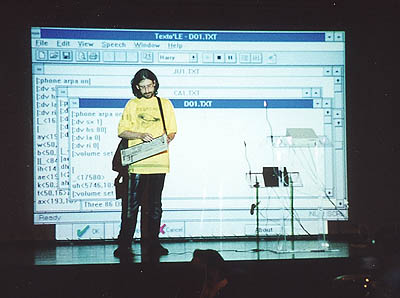

In the early 2000s I saw some creative potential in software art, which could be called the heir to net.art, and organized with Olga Goriunova four Read.me festivals, as well as the repository Runme.org (along with Amy Alexander and Alex McLean), which is active to this day. While working on Read.me, I noticed that software art was following the same path to demise as net.art -- it was gradually becoming absorbed by media culture and new IT products, by digital banality. That was when I began to work with Aristarkh Chernyshev. Our first project, in 2003, was Super-i Real Virtuality Goggles . But that wasn't my first material project after net.art. In 1998 I made 386 DX, the singing computer, and I've given 100 concerts around the world with it.

Web 2.0 marked the end of net.art, as it had to compete with the glut of ideas published on Livejournal and other sites like it, and thus introduced a crisis of originality. Moreover, the inability of political activism to affect policy -- the main shock here was the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq -- cast doubts on its reasons for existence. That brings us to the mid-2000s. With the strategies of the 1990s facing a crisis, we created Electroboutique as a laboratory for studying new strategies in art. We wanted to create media works that were plug-and-play and zero-maintenance. Furthermore, we wanted to distance ourselves from media activism, which had hit a dead end. Since art equals consumption in the conditions of the unipolar capitalist world, we decided to make a commercial object. We put protest and critique in its body. That's how we arrived at our style, which we called commercial protest. Then we added exciting shapes and sound. And that's how we got CritiPop.

-->

You say that net.art "did not create its own economy." That makes it sound like opening Electroboutique was a way for you to survive. You created your own commercial system outside the existing art market, the museum and gallery system.

You're right on the first count, we really were in search of financial independence. We wanted to make a product that would be an interesting work of art and also sell. But we were never trying to build an alternative to the museum and gallery world. As an art company, we are not hostile to that world (though we are critical), or to capitalist society in general. We work with XL Gallery in Moscow and we don't turn down museum shows. Net.art was fun. It was a game and a parody of an art movement. But now, Electroboutique mocks museification and historization.

I'm not convinced that your commercial protest in the form of Electroboutique's products is a sharper weapon of critique than media activism. Even if media activism has hit a dead end, as you say, do you think commercial protest can escape that?

Time will tell, but for now we're satisfied with the result. First of all, we borrow subliminal devices from advertising, so if the viewer doesn't read the critical message right away, he'll still get it. Besides, we've had a lot of feedback from "ordinary viewers," from reputable critics and collectors, and in the vast majority of cases the reaction is perfectly adequate. Of course, there are critics who say: "That's not art!" But we're happy with that, too. It makes us feel like real modernists.

As for dead ends, that's a crisis embedded in the Western idea of progress. The idea of progress assumes the necessity of the new. The new comes to replace the old, only to later go out of date and be pushed aside by a "new" new. Well, with our mind and our sensory organs we know and feel that CritiPop is new today. Just try to convince me otherwise.

Brian Droitcour is Rhizome's Curatorial Fellow.