Atif Akin’s installation, Empire Front, appropriates more than 600 photographs and captions published online at public realm by American or UN soldiers around 7 largest overseas bases of the American Army. A drone vision animation is a part of the installation as a signifier of the strategy to reverse the surveillance mechanism which is often ascribed to power and authority.

Installation is shown in 2015 Articulture Biennial curated by Allison Young.

Work metadata

- Year Created: 2015

- Submitted to ArtBase: Tuesday Sep 1st, 2015

- Original Url: http://empirefront.us/

-

Work Credits:

- atifakin, primary creator

Take full advantage of the ArtBase by Becoming a Member

Artist Statement

Army. A drone vision animation is a part of the installation as a signifier of the strategy to reverse the surveillance mechanism which is often ascribed to power and authority.

Installation is shown in 2015 Articulture Biennial curated by Allison Young.

The Grid

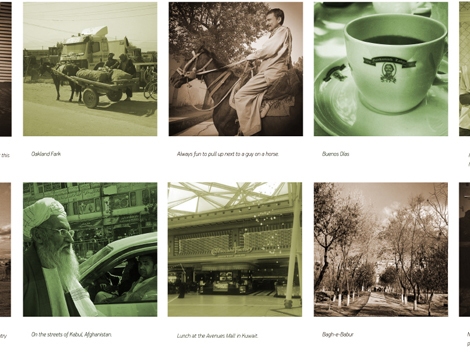

Installation Views The most offensive effects of mass surveillance, so intricately interwoven into our daily existence, have yet to be fully assessed. Contemporary forces such as war, power, rights (privacy), culture (empire), and language are shaped and morphed by surveillance, with momentum and speed that only capitalism can provide. Where are the counter forces to this all-but-complete appropriation of life as we know it? Empire Front, an installation of over 600 polaroid-format photos taken from the social media accounts of American soldiers stationed in US bases abroad, offers a glimpse of one such possibility. The images are displayed in a large-scale grid format, and stripped of their hype color filter, instead toned down in green-gray-brown tones reminiscent of military fatigues and maps. From afar, the grid of photographs looks like a topographical map of a war-zone. Stepping closer, this is classic war documentation—an archive of postcards from American soldiers on the front lines. Alongside the grid is an animation work panning aerial views, gleaned from online satellite imaging services, of those bases where the soldiers are located and from where they share banal tidbits of their daily lives (Afghanistan, Iraq, Kuwait, Somalia, Turkey, Kosovo, Diego Garcia).

There are currently more US deployments abroad than US tourists traveling around the world. Beyond blue jeans and Hollywood flicks, Empire Front, thus, provides a glimpse of what the world sees when it encounters Americans. The postcards are what contemporary Americana looks like, and how Americans respond to, absorb, celebrate, and reject cultures different from its own: one image shows a young, female US soldier wearing a kaffiyeh, a traditional Middle Eastern headdress repurposed as a scarf; another image shows a US soldier posing happily with local children; and yet another image shows an American-based shoe store at a mall in Kuwait. Each image has a caption, authored by the photographer, and alternately descriptive, critical, humorous, ignorant, aware, happy, scornful, or regretful.

The ease with which the daily lives of soldiers can be accessed through those mechanisms created to put private lives on display for commercial, capitalist use is satisfying and horrifying at once. Empire Front provides a glimpse of the mundane machinations of the military-corporate complex, and the limits of innocent, collective participation of individuals in self-exposure. Here we are now, in fact ’surveilling’ the military, exposing the inherent vulnerability of the military’s tools (soldiers), stripped of their power (not in uniform, sometimes naked), and turned onto themselves (camera).

Empire Front plays with the politics of power, including the abandonment of corporate aesthetics and machine language. As such, the unique features of the ultimate corporate power source become almost too easily dismissible, or perhaps simply useless. Empire Front is both innocent and pernicious, offering a thoughtful critique of internet and surveillance culture and American Empire today.

Hillit Zwick August 2015, New York