This report about Ed Fornieles’ recent workshop What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)? is published in partnership with DAOWO, a series that brings together artists, musicians, technologists, engineers, and theorists to consider how blockchains might be used to enable a critical, sustainable and empowered culture. The series is organized by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London and the State Machines programme. Its title is inspired by a paper by artist, hacker and writer Rob Myers called DAOWO – Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others.

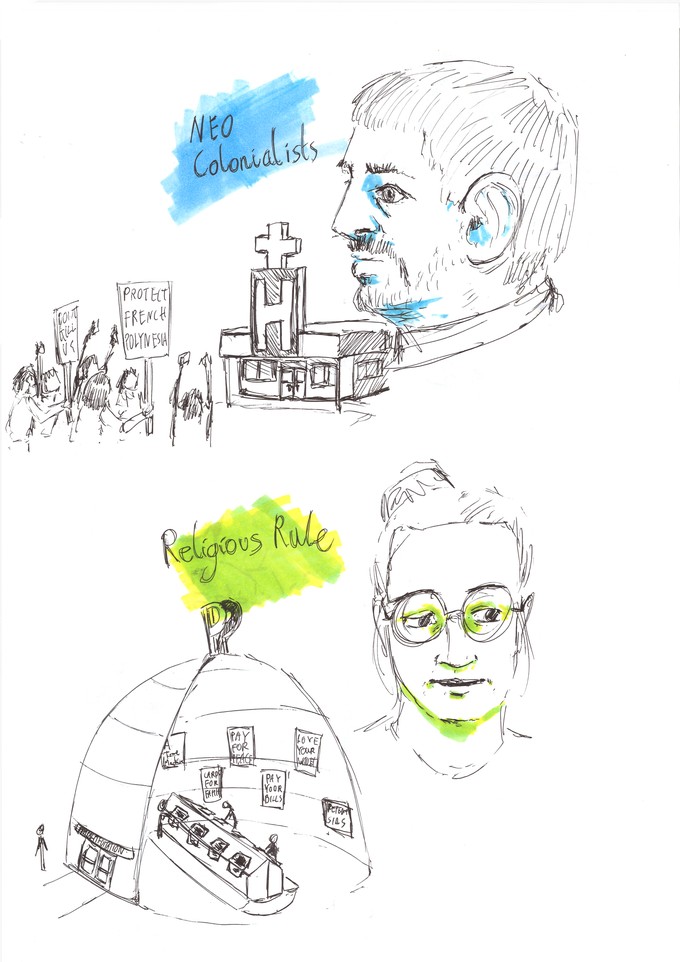

Imagine an island not far off the coast of French Polynesia, floating quietly while it absorbs hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars in crypto capital. Idyllic animatronic palms made of stainless steel manufactured in Germany and coated in organic coconut husk waft gently in the breeze, while an underwater generator noiselessly converts salt water to a drinkable resource. A backdrop of impossibly green hills glimmer with solar panels coated in a thin layer of hyper-absorbent algae, courtesy of a Swedish start-up whose CEO lives in a villa nestled into the landscape. Welcome to the future of Seasteading.

A few years ago, when British artist Ed Fornieles began researching the social dynamics of the blockchain and cryptocurrency, this sort of scene was an ecstatic fantasy conjured up by what’s generally perceived as the delirious imagination of the rich and bored; of opportunistic Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and a pack of wily investors on the hunt for the next lucrative buzz. “Now it’s become our present reality, and it’s not so funny,” says Fornieles of the burgeoning crypto society. We’re gathered in the Goethe-Institut London on a drizzling afternoon in March, and Fornieles, embodying the role of a digital coach and dramaturge, is introducing the concept of live action role play, LARPing for short,to a motley group of around two dozen participants including students, artists, techies, architects, and–unbeknownst to all–IRL Seasteaders in disguise.

Convened in collaboration with Ruth Catlow, co-founder of online research platform and gallery Furtherfield and Ben Vickers, CTO of the Serpentine Galleries, the workshop, titled What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)?, is the fifth installment of DAOWO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization With Others): a series bringing together artists, writers, curators, technologists, and engineers to investigate the production of new blockchain technologies and their socio-political implications. It’s also an effort “explore the hazards of formalizing the idea of ‘doing good on the blockchain’,” according to Fornieles.

Participants are sorted into four groups, or islands, adopting the personas of crypto-millionaires and billionaires in order to configure a speculative society upon the Seasteading frontier. The LARP is organized into four sessions, including a period of self-actualization, where the committee members of each island settle upon an operating structure for their crypto-community; a four-year throwback, where the group reflects upon the success of their fledgling island’s socio-political structure and makes any necessary adjustments, and finally a fifty-year “truth and reconciliation” process followed immediately by a super convention, where each island proudly presents its success story – or laments its struggles – to the broader international Seasteading community.

In order to introduce different practical challenges and ethical quandaries, Fornieles throws two Seasteading communities on artificial islands and two pre-existent (and potentially already inhabited) islands into the mix. While Seasteading technically excludes such “organic” islands, the idea of “mining cryptocurrency in paradise” has mutated into colonizing real communities ravaged by natural disaster, as many critics including Naomi Klein and Nellie Bowles of the New York Times have noted about Puerto Rico. He’s also established a dozen roles for participants to assign themselves: from Ministers of Religion and Education, to Island Architect, Mayor, and Chief Technology Officers, in order to jump-start the camaraderie (or anarchy). “For first time role players, there’s a tendency to be the sociopath you always wanted to be,” cautions Vickers in the warm-up introduction. “Please try to suppress this desire.” Otherwise, it’s game on, and immediately after we separate into groups, all kinds of strategic and ideological questions emerge: Do we want a central government, or is it best to leave politics to algorithms? Should we convene a Church of Something, or are we all too woke for religion? Do we need a justice system, a formal corrective center, or a Sims-like human rating system to self-regulate behaviour? Maybe we can just vote people on and off the island?

I’m relieved to be sorted into an artificial island established by Paypal founder Peter Thiel, therefore bypassing what plenty of cultural theorists, including Klein,1 have pointed out as the immediate and unmistakable stench of neocolonialism. We’re given a name, “The Pilgrims,” and a socio-political disposition: as “Modern Libertarians,” we’re supposed to be a “free-thinking community that believes the only way to create an honest, new, distinct way of living is to set sail and create a new network.” Filled with neoliberal buzzwords like innovation, entrepreneurialism, and disruption, Pilgrim Island is the paragon of Seasteading ideology. Oh, and we’re really into wearing all-black hi-tech athleisure. Seriously–it’s the stuff of neoliberal dreams.

But without a pre-existing ethical quandary to mediate, the need to immediately establish an ideological commons stays airborne. The island’s socio-political landscape ricochets between one participant’s idealized utopia and another. Still, whether by defaulting to their actual areas of expertise or diving head-first into a full-fledged crytpo-billionaire alter persona (I suspect the former), the founding committee of my island quickly jumps on their self-assigned roles. I note with interest as the player to my right, a small, sassy woman sporting a bowler hat, a markedly “business casual” blazer, and big, blinged-out hoop earrings, promptly elects herself mayor without much resistance from the rest of the group. Almost as if by reflex, she launches into a compelling speech that touts the glory of the hands-off and unregulated economy of Seasteading; the imminent intellectual and financial capital to be gleaned from the “limitless potential of high-tech islands based on real life values.”

Things quickly slip off the deep end. Less than twenty minutes in, the island’s architect has gone on a minimalist-inspired rampage, apparently inspired by a very jovial spiritual pilgrimage with his “good friend” Elon Musk to Vegas. Conjuring a Panopticon2-like self-corrective facility-cum-worship center in the middle of the island known as the PayPal Meditation Center, the architect introduces an elaborate system of self-enacted punishment for residents involving a penny-by-penny payment for one’s sins fulfilled by the obsolete performance of extracting Real Money from an ATM (the horror!). Meanwhile, the Minister of Religion is busy ordaining a Thiel-inspired sect that ties spirituality to physical health, brandishing a harsh, zero-tolerance approach to dissenters.

She colludes with the Minister of Agriculture to debut an all-seeing pineapple that simultaneously provides sustenance to Pilgrim Island’s speculative inhabitants while also monitoring their spiritual commitment. The Minister of Education crafts a secret p2p anarchist boot camp on the Northwestern coast of the island, for the self-conscious younger generation eager to find deeper meaning in this brave new digital world. For a reason that still escapes me, Peter Thiel is then involved in a tragic water-taxi accident that ends in the ultimate demise of he and his partner. A referendum is held for a new leader amidst the for-profit utopian soul-searching…

As for myself? In order to preserve proper journalistic objectivity (obviously), I’ve self-identified as a ghost (more specifically, the ghost of reason). This works great at first, but when we hit the four-year benchmark, I learn the Minister of Religion has been voted off the island, a movement initiated by the Energy Manager and Local Representative. As the spiritual attachment, I also get the boot; we’re shipped off to a neighbouring island called Blue Frontiers that’s likewise self-fabricated, and also exhibits the same weakness of a spiritual void. With an algorithmic overlord, the (not-so) speculative island is situated after the unfortunate ravaging of French Polynesia by an unavoidable natural disaster: A narrative that oddly parallels that of Puerto Rico. Fast forward 50 years into the future, I am welcomed to join them in a painful process of reflection.

We quickly learn that an existential ennui due to lack of faith and purpose amongst the island’s population has led to a mass suicide. “There have been lots of residents killing themselves, but our technology is so good, can it really be that bad?” asks the island’s hands-off Mayor, who apparently doesn’t believe in building. Having fired the Architect early on (“We’ve all enjoyed the beach, why pollute it with architecture?”), whose algorithmic approval rating sits at a measly 32%, the Mayor proceeds to gloat over his 90% approval rating, while the Chief Technology Officer also curiously boasts a sky-high rating of 96%. Suddenly, Pioneer Island’s schizophrenic governance starts to look pretty good.

_large.jpg)

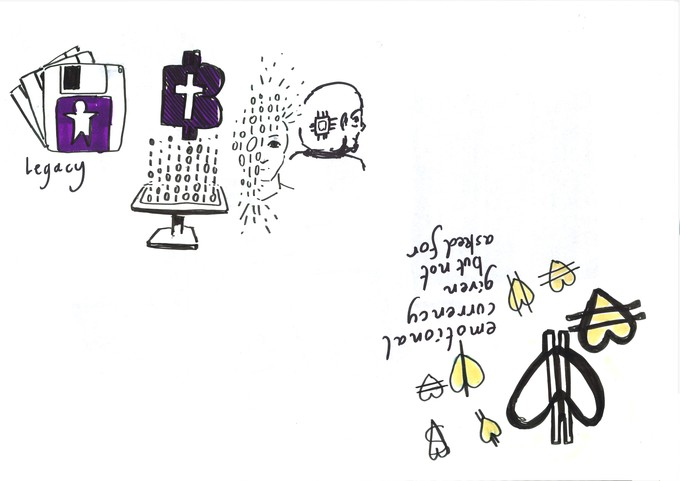

Minutes later I find myself at the mid-century International Seasteading Convention, where I am exposed to the triumphs and tribulations of our near-present Seasteading future. Alt-right acceleration gives way to a hyper-libertarian group named Sol declaring allegiance to a new religion steered by Crypto-Christ that touts a new hedonistic world order, completed by furnishing its children with sex robots. An Anarcho-communist community has catapulted its Mayor and Minister of Education to a new planet, and tout the great success of introducing an emotional currency to the island’s residents while skirting around the issue of a veganism-inspired massacre. “We’re leaving a very beautiful piece of archaeology for other nations to learn from,” the Mayor proudly asserts from her new life across the galaxy.

An animatronic tear rolls down my cheek as I hear the recent struggles of Pioneer Island. With their reputation system based on the blockchain overloaded by a sea of new residents, their dwindling natural resources (“We have plenty of crypto, but no food or water”) leads to an appeal from the rest of the bitcoin billionaires to lend a helping digital hand. Still, the Mayor remains unshaken, once again delivering a solid speech that praises the blockchain mantra of “pioneering small, self-organized projects that lead to independence,”; of “never aiming for total cohesion and never following democracy,” but instead “generating local, self-sufficient systems” in order to achieve success.

Curiosity takes over, and I approach the brilliant spokeswoman after the workshop winds up in order to uncover her background. Turns out she’s none other than Nathalie Mezza-Garcia, the self-termed “Seavangelesse” and research strong-arm of Blue Frontiers. Currently pursuing a PhD that investigates the politics and sociology of Seasteading at the University of Warwick, Mezza-Garcia was recruited by the Blue Frontiers team in 2017. Now, with the company just months from unveiling to the public its island off the coast of French Polynesia [after this report was filed, the island nation pulled out of the deal –Ed.], she’s keen to spread the message amongst the masses and change some minds. Naturally, we go for a drink.

“If someone like me who basically lives and breathes Seasteading 24/7 can get so much wrong, it’s no wonder the general conception of Seasteading is so far from the truth,” says Mezza-Garcia. “The biggest mistake people make is laminating the ‘evil billionaire’ narrative onto the whole enterprise.” Still in the midst of her research, Mezza-Garcia has nothing but admiration for the wealthy patrons of Seasteading. Rather than using the enterprise merely as a tool to acquire more capital, Seasteading companies like Blue Frontiers are more interested in the limitless social, political, and ideological benefits awaiting this post-human frontier, she argues. “It’s a step into a world where we all have more decisions.”

As for the regular members of society who can’t afford their own slice of animatronic paradise on the enlightened blockchain, hotel accommodation will soon be available on Blue Frontiers’ islands. For now, role-playing is a valuable exercise for warming up a heterogeneous batch of the general public to the idea, so they can form their own opinions. For Mezza-Garcia, What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)? is the first time she’s seen artists – “instead of libertarians or blockchain people” – engage with the principle ideas of Seasteading in a direct, open, and low-stakes way; many attendants of the workshop voiced a similar sentiment (but thought another round or two of role-playing would help them with the trickier bits–like avoiding vegan anarchy, or summoning a Bitcoin Jesus).

As the once-distant dream of Seasteading is eclipsed by its imminent reality, the potential of role playing as an educational strategy emerges on both ends of the chain – but the takeaway is by no means consistent. Eager to make the operations of Blue Frontiers accessible to a broader audience, Mezza-Garcia celebrates activities like this as a potential source of new recruits. She even intends integrate LARPing into Blue Frontiers board meetings to encourage a top-down empathy with non-billionaires of the blockchain. Yet the results of the workshop–in which speculative future Seasteading communities are ravaged by a despairing lack of faith, suicides, and massacres–paints an entirely different story: One that becomes increasingly problematic when one considers the flawless criminal, mental, and physical health records Blue Frontiers’ selection process requires, alongside the obvious economic factors.

For a community keen to “enrich the poor, cure the sick, and liberate humanity,” according to Blue Frontiers’ co-founder Joe Quirk, their operating logic seems to reinforce many of the social stigmas and power structures already responsible for much of the suffering and inequality within contemporary society. Rather than offering any single narrative or conclusion, LARPing underscores these divergent visions of Seasteading’s (failed) utopia just before the ship sets sail.

All illustrations by Maz Hemming.

[1] In a piece published on The Intercept on March 20, Klein blasted Bitcoin as “the most wasteful possible use of energy”, characterizing leading cryptocurrency figures as opportunistic “Puertotopians” keen to capitalize on the hurricane-ravaged island of Puerto Rico. Klein also equates the “wealthy libertarian manifesto” of Seasteading to the colonizing powers of the new world that seized once-free nations and converted their indigenous inhabitants into slaves.

[2] Though conceived by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century, the idea of the panopticon was popularized by the French philosopher Michel Foucault in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish. Says Foucault of the Panopticon’s unlucky captive: “He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication.” Remote island or bustling city center, the Panopticon’s relevance has resurfaced in the realm of the digital; see Thomas McMullan’s 2016 piece in The Guardian about the relevance of Panopticonism amid the cross-fire of data capture and digital surveillance.