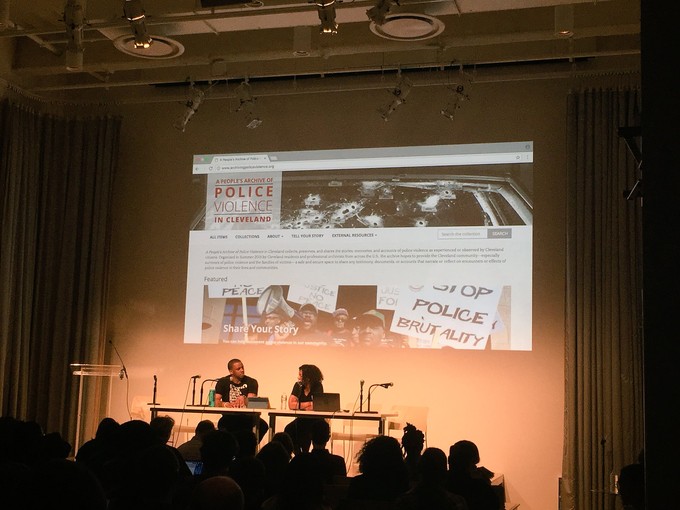

Below is a transcription from the National Forum on Ethics and Archiving the Web––organized by Rhizome (in collaboration with the University of California at Riverside Library, the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, and the Documenting the Now project)––which took place in March of this year. See full information and the video archive for the event here. This conversation between Jarrett Drake, advisory archivist of A People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland, and a doctoral student at Harvard University's department of anthropology; and Stacie Williams, the team leader of digital learning and scholarship at Case Western Reserve University Library, focuses on the People's Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland's conception and development, lessons learned from the process, and its potential as a post-custodial model for other grassroots organizations protesting various forms of state violence.

Stacie Williams: I'm Stacie Williams, and I manage the digital scholarship program at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Jarrett Drake: I'm Jarrett Drake. I am now a doctoral student in Social Anthropology, and befallen archivist, but this is like the fourth or fifth time I've seen a bunch of archivists since I quit, so maybe I really didn't quit after all.

SW: Every time you try to leave….

JD: ...something keeps pulling me back.

SW: What do you remember about how you got involved with the People's Archive, and what was the situation, or conversation, that drew you in?

JD: I think that in the immediate event, obviously was in May 2015 when Michael Brelo, who was a Cleveland Police Officer, fired--I've actually forgotten the number of shots it was that he fired––

SW: 137, I think.

JD: ––bullets into the car that had Malissa Williams and Timothy Russell in it. That incident, I believe, happened in 2012. His acquittal on all charges in May 2015 was the breaking moment for me, and this followed so many other non-indictments. Obviously, less than a year before then, Michael Brown had been killed. So, you just keep getting image after image, story after story, of law enforcement killing black folks, and walking away, getting paid leave, getting literally “away with murder” to quote Shonda Rhimes' television show.

That was it for me. I was in New York when I saw the news of it on Twitter. We didn't even know it was going to be a project at that point. It was just people being mad on the internet together, and honestly, the ability to find other people to be mad with, and move that anger into action was what drew me into it.

After that, all of these events cascaded. It all started on Twitter. So, Stacie responded to this tweet asking if archivists who were going to Cleveland for the annual meeting wanted to do something, and Stacie was one of the first people to say, "I'm in."

So, my question to you is, did you think that we'd wind up collaborating to create this, and what were some of your minimal hopes or expectations when you replied that you're in?

SW: I think, I would say that for me, it was very much the same. People were mad on the internet together, and it felt especially acute for me because almost every day, there was this period of time where, there was autoplay, dead black person after dead black person. I had compared it to essentially having snuff films in your live stream, which I refused to watch. To this day, I have watched none of those videos. I really could not because maybe three weeks after my first son was born, Michael Brown was killed.

My feelings in that moment were of frustration, and of anger, and feeling not just that I wanted to do something, but that I wanted to do something for my son, and all of the other sons, and all of the other mothers. That feels important and meaningful. I don't even think that I knew that it would become this. I hoped that whatever we were able to do would provide the ability for other people to speak their truth and be heard in a way that we were not being heard through the justice system.

So, then I'd ask, how did you feel during this act of memory creation? When we were out on the streets doing oral histories with Cleveland residents, and then, on the back end, helping transcribe, or helping set up the frame work for us to have the website, and working with the developers, and talking to Amazon, and just all of those things?

JD: This might sound a little dramatic, but honestly, as soon as I started to really get involved, especially as we got close to the launch day, we did all this stuff over Google Docs and conference calls. It didn't yet feel real. It seemed like we were just trying to gather ourselves enough just to get there.

I went to Walmart. I hate to say that I went to Walmart. Trash, right? Dammit. I was broke. So, I went to Walmart to get some cheap digital recorders, and I think it was the Saturday before. I was like, dang. I think we're about to do something that's gonna transform us individually and hopefully, transform other groups of people collectively.

When we started putting the website together, the first draft was not what we wanted it to be, and we deleted it. Through that whole process, I just felt that chains were falling off of me. I felt like chains were falling off of the way I thought about problems. I knew probably then, I was gonna quit my job. When we were out there in the streets, and it was hotter than a mug, I remember cramping up and I was just like, this is it. This is not the climate-controlled reading room, or the stacks, or the staff meeting. This was the reason I had decided to be an archivist in the first place. It was completely seismic, and I don't even think I've had the time to honestly reflect on how much those kinds of moments really impacted me.

The next question I have for you that builds off of that is, what's one part of this project, or one story that will stick with you the most and be impossible, for better or worse, for you to erase from your memory?

SW: I think, there was a point after the archive had gone live, and it had been up for several months at that point. We were having a conference call with the other advisory board archivist, and I had just given birth to another child, and we're waiting to close on our house in Cleveland. I would have never thought that less than a year later, that I would be a citizen of Cleveland, and therefore, feeling like I had an even larger stake in these stories and how they were being told.

During that conference call, we were staying at my in-laws house, and I was trying to nurse, and trying to find privacy, and one of the kids was fussing, another one was hungry. But I felt like it was really, really important to still be on that call, and still have a voice, and still continue to see things through as well as we could for the activists involved.

But literally, sitting in my hands was this other really, really large responsibility, and someone to whom I also owed a great deal of my time and energy. Here are these two very important things, and they aren't separate. They're a part of what this life looks like, and there are hundreds, thousands, millions of other people doing that same thing: trying to really integrate the activism that they do with their real lives, and taking care of people.

JD: Can I ask a follow up to that? Which is that, we spent a lot of time organizing this project, on our own time, and own dimes, and also on some of our employers time, and our employers’ dime. It wasn't always readily apparent to those people in our lives, whether they are family members, or partners, or co-workers what the hell we were doing, and why we were doing it. How did you explain to those people who all need and depend on us in different ways what you were doing and why it was taking up so much time? Were you able to explain it easily? Did it come with difficulty?

SW: That's a really great question. I think, because we started while I still lived in Kentucky, and I didn't have family in Kentucky outside of my immediate family that I built with my husband and my children, I really was just explaining it to him. And he's a journalist, so I think he understood pretty well what the stakes were and why it was important.

I didn't feel like there was an issue there in trying to explain that I wanted to be involved in this. I think, really though, I was a lot harder on myself in those moments where it felt like, wow, this is a lot to balance, and maybe I'm doing a really, really bad job.

There were conference calls that we took where I had to mute myself half the time because someone was screaming in the background, or someone always wants to say hi, and it's like, no, this isn't your call. So, yeah. Feeling it, explaining it, and making it okay for myself. That's also something I got from a lot of other people who are engaged in organizing work, is that you tend to really be the hardest on yourself, in terms of trying to juggle those things. You might have people in your life who are extraordinarily understanding of the work that you're doing, and they're super supportive, and it's you sometimes. Looking in the mirror and trying to figure out what's enough. How did you explain this work to your partners, your friends, your family?

JD: Honestly, I didn't really explain it that well, because I didn't know what we were doing. In retrospect, it seems clearer now than it did going into it. May 2015, I couldn't have told you what September 2015 was going to look like. I couldn't have told you that that fall, I was going to be spending a lot of time learning from a lot of people about how to pull apart the PHP website. Thank you, Ruth [Tillman], filling in for that. The generous amount of time she gave.

These are the things that I just couldn't see, so my partner definitely asked me a couple of times, "You got another call to get on? You got another email to send?" One time in particular, I was visiting her, because we've been more or less long distance for a while, and Trella called me. Trella Gardener is one of the folks in Cleveland who got involved with our project very early on. Very lively, lovely, beautiful black woman. One of the ways you're gonna understand Trella: her Twitter handle is @1noseygrandma. That's her Twitter handle, so she's that nosey grandma.

I love her, but she called me one time, and I had to pick up the phone. I was with my partner, and she could hear Trella's voice and intonation, and she started busting up. She's like, "Oh. That's what you been doing this whole time?" She understood so much just by seeing, well in this case, hearing the voice of someone who has been involved in this.

In terms of explaining, I don't know if I necessarily did that very well either. I think for the longest time, I was trying to act like I wasn't doing it. I had a shared office at the time, so I'd be on these phone calls, or doing a whole bunch of emails, trying to act like I wasn't [working on this project]... After a while, I just started being upfront about what I was doing, and what mattered to me.

I started putting up post-it notes on the outside of my door, which faced the reading room. Post-it notes that were memorializing and marking that black women and girls were being killed by the state, and by intimate partner violence. I was tired of acting like I wasn't aware that black people were being slaughtered by police and by other black people on a regular basis. I put these post-it notes on my door, and one day the University Archivist walks in, probably to ask me about picking up the digital records at the Dean's office, and he was like, "What are those post-it notes on your door?" I was like, "Oh. Those are black women and girls who've been killed by police and through domestic violence and they've been mostly erased from the mainstream media."

He just wanted to get the latest update from BitCurator. He wasn't ready for all that. I think those are two moments that allowed me to be a fuller version of myself, and not try to segregate professional archivist, like Jarrett from Uncle Pookie. These are the same people. I can't act like the work that we're doing at this institution is irrelevant from that.

SW: I didn't necessarily feel that I had to hide it from work. And not only that, but one of the presidents of the Oral History Association, Doug Boyd, worked right down the hall at that time, and was very helpful in helping me work through considering an ethical framework for a consent form that allowed us to provide as much safety as we possibly could for the people who were participating. And he helped envision different ways in which the people could document and be on the record, but with a degree of anonymity, either with that recording, or with the metadata. You could have a back end of things, but the front end would allow them to remain anonymous.

Let's talk about the process of documenting what we did, because this was the other part of it. We had written an article for the special issue of Journal of Critical Archival Studies. This article detailed this process of documenting the project, and not just the manner in which we documented what we had done, but [how we] documented other people's memories during the project, and also our process of remembering the collective racial history and collective memories of terror in the research that we had to do for this project. How was that for you?

JD: That was one of the harder things about this that I don't think I was really prepared to handle. Because in my job, when I was a Digital Archivist at Princeton, more than anything, my main responsibility as a digital archivist was to document what I did. I actually can't even remember what I used to do on a day to day basis. I know a big part of what I did was create manuals and workflow documents. I became really good at that.

When we were doing this in Cleveland, I wasn't thinking that we were going to eventually need to explicate our process, and that took way more time, the initial setup of everything. I would say the nuts and bolts of everything was in place by September-ish. There were other things that needed to happen, but a lot of that initial labor was from May 2015-September 2015, and once that ended, I thought, “okay, now we can move on with our lives?” I don't know what I thought was going to happen, but what actually happened was we spent a lot of time writing this article, doing research about it, trying to be reflexive about our own process, and not romanticize. Not give in to meta narratives, because we got a couple questions about things we would've done differently.

I don't think many people are able to go about that process in a way that creates genuine guidance, or just transparency for other people. We took a lot of time with that article because we wanted to do it right. We wanted to have our story, collectively, on the record, on our own terms, about creating an archive for people to be on the record, on their own terms. It seemed pretty meta, but it was so critical, and I'm glad we did it. I don't know if you had similar or different thoughts about that process.

SW: One of the hardest things that I had had to do was finishing that article on deadline. I can remember that point at which we had missed deadlines. We missed deadlines on deadlines for that article. Shout out to Rickey and TK for being so patient. But I can remember in that process, calling and being like, are we still going to be able to do this? We had this Google Doc that was a couple paragraphs and the Trello boards, and we phone in.

This was the act of remembering while there was also still so much stuff happening in the present. I'd start out the morning fully intending to write some things, and then there'd be another autoplay black death video making the rounds, and that would shut down my entire day. Or I'd try to save what little I had left at night for my family.

I remember calling like, how can we do this? Are we gonna be able to finish this? And then having it turn into this really collective, caring example of how to really finish a project. We called each other once a week for an hour, and we would sit on the phone, and literally type out the paragraphs sentence by sentence. This sentence goes here. What do you think about this sentence? I've added this chapter. So really, just taking hands and saying we're gonna do this. We're going to get it done, and do it together. I think that really exemplified the whole process as this really massive effort on behalf of so many people, and perhaps we were fortunate in that we were offered platforms to be able to talk about it with other people But the act of getting there and having to discuss that with people all the time in that way was super challenging. With that, is there anything that you might've wanted to do differently?

JD: Yes. Lots of things. I'll just say one that seems basic, but I think it illustrates so many larger points. We go out to Cleveland to create this collection of oral histories, right in the streets. We were at a recreation center; we were at a public library; we were outside a women's shelter; we were outside a home. We were in the mist of Cleveland. One of the things I wish we had done was provided food to people who were in those spaces. That may seem basic for people in this room who have food security, but for people who have food insecurity, I think it would've added much more ... met a basic need.

Some of our recording stations did have bottles of water, and there were some people who literally just wanted something to drink... it was hot as hell! Like, can I get something to drink and leave? I wish that we would've put more of an emphasis on meeting basic needs, and that could've happened differently. Partly, we had no money. Eventually we did a CrowdRise campaign that some people in this room, and people watching on the live stream contributed to, but that was just to keep the lights on. That wasn't to put food on the table. We could have thought about snacks, or just something to help sustain people. If they didn't want to give us a story, maybe they just wanted to get something to eat, and chop it up otherwise.

I think that often times, as documentarians, we can go in and think about what we need, what our agenda is. We could have more actively centered the needs of the people who were going to be in the space, whether they wanted to talk to us or not.What do those people legitimately need? Food insecurity is such a big problem in so many parts of this world, and certain parts of Cleveland especially, so that's one thing that I think I would do differently. What about you?

SW: Now that I know Cleveland a bit better, and if we had had more people, maybe we would have been able to mobilize and get out to the suburbs. So, so many black people from the city have migrated to the inner ring and outer ring suburbs. Those stories are every bit as potentially terrifying as what has happened in the city, or things that we had heard about in the city.

Just a few months after moving to Cleveland, my husband, who's in a fraternity, had gone to visit frat brothers, most of whom live in these suburbs of these other cities that are not Cleveland. He'd been out late which wasn't anything in and of itself, but as he was leaving he called me and was like, there's a cop behind me. I guess, because they were so deep in the suburbs, it was super, super conspicuous that all of these black people were living this house at two or three in the morning.

At that point, I had gone to sleep because it was so late. I was very tired. I put the phone on my desk, so I did not hear it ringing, and he had been calling me. This was so, so soon after Tamir Rice and the Brelo acquittal. I woke up in the morning after seeing the missed calls and the news I was just terrified, cause I didn't even know where some of those suburbs were.

I think had we had even more people, or more engagement, or a chance to do it again, I would absolutely have said, "Yo. Let's make sure we have somebody in Garfield Heights. Let's make sure we're talking to people in Solon. Let's make sure that we're talking to people who live in Akron, even, or Canton." Just because the scope of it is so vast.

That was the bulk of the questions we had for each other, so we'd love to open it up if anyone in the audience has questions.

Image Credit: Caroline Sinders. To watch the full video of this conversation, visit the Rhizome Vimeo.

Image Credit: Caroline Sinders. To watch the full video of this conversation, visit the Rhizome Vimeo.

Audience: Hi. Thanks very much for all this work, and all the love you put in this. I was wondering if there was anything you could share, either anecdotally or statistically about the folks who are using this archive, and how it's empowering communities, how it's being used by researchers, and how you feel about all that use?

JD: One usage of it, actually has been as an educational resource in different LIS programs that have asked different groupings of us to speak to their classroom. So talking to librarians and archivist-in-training about this has been something that all of us have shared in doing. People have, in those grad classes, been looking at this in advance.

One time, it was really awkward. A historian was teaching the class, and wanted to point her students towards the website, and all of the files were offline. She sent me a message, and she was like, "Where's y'all’s archive?" I was panicking. But it was just a small glitch...

In terms of other types of usage, we have a Google Analytics running on the site. I will confess, I have not looked at them, so I don't know where our hits are coming from, or how long people are staying there. I work in a brick and mortar institution, and we would think of usage as people that walk in through the front doors, and check out something, or request something to be viewed in the reading room. But if we think of it more in terms of the people who would get something from this being created, I would say that one usage, that I do hope is a usage, is that a lot of people got something from this at the moment of creation. If we think of usage and access in those broader terms, who's getting something from this, and what are they getting?

I definitely heard stories and saw, as other people were interviewing folks, that people were getting something out of that act of just telling their stories. You took part in even more of those events after you moved there, especially with going to the youth jail.

Audience: Absolutely. So, in terms of use or measuring impact, you're absolutely right. We tend to look at it from this very quantitative standpoint: how much, how many. To the extent that the archive is still a living archive. The activists could still be adding things to the archives, to the extent that say, if we had done an event, as we did at the public library to capture more oral histories. I think in terms of numbers, the day ended with about eight of them, but there was a huge round table of people who were just talking. Just residents from the community having the conversation, even if they didn't necessarily want to be recorded. Just being able to share their experiences, talk about these commonalities, and even further talk about ways to resist police violence.

Going to the jail, we had done a training exercise of it at the juvenile detention center. The young men in there, once they started seeing how it worked, and interviewing each other, they were so open and so wanting to share. It seemed to be so very meaningful for them. I think the uses could be really vast, but we're not necessarily counting that in the same way that we typically would in an academic institution.

JD: Right.

Audience: I want to ask a little bit about something that we've touched on a lot here, which is the surveillance state. There was a really great remark that someone made in one of the panels this morning about when you're archiving the stories of people who are marginalized or who are potentially victims of state violence. There's a line between wanting to protect their privacy, wanting to make sure that the presence of their stories on the internet isn't potentially re-victimizing them and being paternalistic. How do you respect their agency in possibly wanting their story to be out there? How do you think about your archive in those terms?

SW: Well, one of the reasons we were so specific about how we tried to set up that consent form was that it wasn't just that we were setting it up in ways that we felt like would protect people, we also considered our communication with participants as a critical piece of what we were doing. It wasn't just here's the form and sign. It was, okay, we have this form so we can tell you what some of these things mean on the form, and that for every possible category that you could check, here are potential repercussions of that. Some could be good and some could be bad, but we wanted people to feel informed, and that it wasn't just that we were giving them a thing to sign. I think, we tried to avoid feeling or acting very paternalistically in that way, by just simply making sure that people were informed about what the forms actually meant.

Audience: I was really deeply moved, Jarrett, by what you said about not being able to be yourself and be an archivist at the same time. This concerns me deeply as an educator, and I'm wondering if either of you could comment a little bit on what can we do to make established institutions much more hospitable to people like yourself, who are motivated by wanting to change the world? You said, once I did this project, I knew this was why I wanted to be an archivist, but I can't be an archivist doing this project. I have a great deal of empathy for that. I'd love to hear your insight on what we could do about that.

JD: I think way more institutions need to be explicitly anti-racist, black feminist institutions, which is hard, because lots of institutions are either explicitly or implicitly fine enabling and supporting white supremacy and massaging a war on a daily basis. I think that we need to have more of those conversations in archival meetings, and listservs, and all of those spaces where professionalism gets codified. Lots of talks about diversity that happen within libraries and archives end up being this very liberalist conversation. We are actually in need of social, political transformation.

I don't know how anyone could be, especially under this U.S. President, convinced that we are in need of just a little tweak. We have some structural problems and institutions are either going to be a part of that social transformation process, or they'll become agents of fascist propaganda, which honestly, the American Library Association is deeply... that kind of stuff, that's why I left. I think we have to have more of those explicit actions by institutions or organizations and they have to be willing to risk something.

Truth is, most of these institutions, especially the ones that have predominantly white people, they can withstand those risks. If a white person gets killed by the state or by a citizen, usually, there's consequences. When black people put ourselves out there professionally, we aren't really as protected. I need more of those institutions to take more of those institutional risks.

SW: I would definitely say that within those institutions, there have to be more people of color brought to the decision making tables. Diversity gets thrown around. We have all the fellowships and the things. Both of us are spectrum scholars, for instance.

What happens is we are largely placed in institutions where we have very little administrative power. It's not that everybody ends up going on to become a supervisor or something. That's not even necessarily everybody's desire in life. But to the extent that our input is sought, and engaged seriously, and that we have the opportunity to really make real decisions, or be brought to the table to make real decisions in an institution...that's the only way you really see change. They’re not necessarily set up in a way that your average processing archivist gets to come in and make those types of changes. Sometimes, even make those types of suggestions. Making room for a lot more people to have a seat at that table.

JD: End it with a Solange reference. Damn. This is great.

SW: Not totally by accident.