Though some might insist on virtual reality, or VR, as a passing fad or technological gimmick, the field has a prodigious and often inspirational agenda, full of possibility and potential upheaval. In fact, VR might have the ability to displace one’s perspective into an unfathomable mixture of altered states and tightened sensorial elasticity. Although most conferences that cover VR tend to exist on the corporate, high-budget, and ostentatious spectrums of production value, the second annual Open Fields conference focusing on “Virtualities and Realities” and held in Riga, Latvia, took a more critical approach over merely celebrating the field. The two day event featured six keynote speakers, eighty presentations by artists, activists, researchers, students, and biohackers, three exhibitions, and a wide array of live and immersive performances. Participants representing dozens of countries spoke on their vision for the future of hybrid spaces with the ability to remix material and immaterial landscapes. The talks were varied, covering everything from interactive art and VR to experimental sound and performance art. The aim of the event was to not only celebrate possibilities within the fields of virtual and hyperreality, but to also question and critically engage with their content in order to redefine what the field could become.

A central theme of Open Fields was the interdependency between our social habits and prejudices and how this relates to the production of computer software. Programmers’ algorithms are increasingly designed for premeditated social profiling rather than fostering an expansion of social exchanges. In her 2016 New York Times article, Kate Crawford wrote, “Sexism, racism and other forms of discrimination are being built into the machine-learning algorithms that underlie the technology behind many ‘intelligent’ systems that shape how we are categorized and advertised to.” This problem stems back to the technological origins of these algorithms, namely, the Internet and GPS, both projects first funded by and developed through U.S. military and defense research.

Mark Zuckerberg at Samsung's press conference at Mobile World Congress, 2016

In her opening keynote, Monika Fleischmann, co-founder of the interactive experience design company art+com, spoke about “shades of virtuality,” or “the transition from being to becoming,” arguing that we can anticipate the evolution of VR as a mixed reality system that allows users to maintain an awareness of reality while infusing them with a new appreciation for cognitive overhead. In order to illustrate how VR (as opposed to AR) provides endless alternatives to physical spaces while simultaneously blocking out the real world, she showed a popular meme photo of Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg steering us into his company’s version of reality. Although everyone in the audience was wearing a headset, Zuckerberg refrained from donning the device, an image that coyly suggested his control over his many users. Ultimately, she finished her talk by showing a clip from “The Void,” a hyperreal, whole-body interactive experience owned by Disney that transports the public into a real-time immersive environment that aims to combine VR and AR worlds.

Traversing from the world of synthetic realities into the natural or physical world, David Rothenberg gave the next keynote, in which he described compositions he designed to interact with whales and dolphins. Rothenberg is an anthropologist and author researching how the natural world can connect to the technological one through sound, as well as a professor of philosophy and music at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. In working with nonverbal mammals, to design sonic rhythms that permeate underwater climates, he found how machines can become a translating mechanism for performance and communication. Though the concept of ubiquitous technology is nothing new, Rothenberg asserted that technology should evolve to the point that machines become an extension of ourselves, so that we forget they are present. He noted that we are progressively advancing towards this state, as computation becomes cheaper and easier to embed into our daily lives.

Video of Time-Body Study, Daniel Landau, 2016.

Also examining the connection between physical materiality and virtual spaces, Daniel Landau’s “Time-Body Study” explored how VR could allow us to have experiences beyond existing human limitations. On everyone’s minds were the obvious solutions of flying and breathing underwater, but Landau’s focus was on how the tactile aspects of the VR experience could altered to influence our sense of perception. He selected a volunteer from the audience and asked them to wear a VR headset, through which they could see an outstretched arm. He asked the volunteer to stretch out their own arm and place it on a table. Another volunteer was asked to touch the arm of the first, while a VR hand inside the viewing space did the same. This effect attempted to reveal how our brains respond to virtual, phantom stimuli inside of an artificial environment.

Looking to the future of interpersonal relationships in this context, a number of speakers described ongoing projects that augment possible connections between strangers. Karen Lancel focused on her work on kissing experiences, translating a kiss into bio-feedback while asking the public to describe why people kiss and what it feels like to kiss. In her EEG Kiss Cloud, participants kiss in a public space in front of onlookers; EEG data analyzes their kisses, and this data is projected in a circle on the floor around the participants, suggesting a public form of reclaiming intimacy through technological intervention.

Video of EEG Kiss Cloud, Karen Lancel, 2017

Brooklyn-based artist and neuroscientist Sean Montgomery put forward the premise that interactive art is a driver of scientific research and progress, and that we should look to artists to help us imagine the future of technology. His project Livestream exemplified this synergy. In a playground in Kentucky, he installed a series of yellow pipes which measured data such as pH levels, conductivity, temperature, and turbidity, from fresh water streams in the neighboring area. Montgomery worked with a local composer to translate this data into sound. The project attempted to sonify an existing but obscured ecosystem to make it more relatable to people occupying these spaces. Montgomery also debuted his collaborative performance piece with LoVid, “Hive Mind,” in which two performers engage the audience in a nonverbal discussion on stage, such that the “brain rhythms of each performer directly generate pulses of light and sound that synchronize the brain oscillations of viewers and create an immersive environment that transports the audience to altered states of consciousness.” Although I missed watching the performance live, I saw how its potential could be scaled to events with thousands of participants, in order to influence the collective mindset of the audience.

Produce Consume Robot, LoVid, and Diego Rioja, Hive Mind, 2017. WARNING: THIS WORK PRESENTS A SEIZURE RISK IF YOU HAVE PHOTO-SENSITIVE EPILEPSY.

Several speakers examined the larger concept of how interactive art has permeated our lives, becoming ever more commonplace and relevant. Varvara Guljaveva spoke on the field’s “unsolved question”: how, since interactive art has reached a stabilization point that allows critical and conceptual discourse to occur, could artists build beyond basic technological descriptions? The audience could indulge in the idea that new media art, however pervasive, can help parse and critique the transition from the older sharing culture of Web 2.0 into current states of the web – as a surveillance vehicle for data mining and the extrapolation of culture.

Two keynote presentations by Ellen Perlman and Chris Salter reiterated a guiding belief echoed throughout talks at Open Fields: that virtual systems are becoming so innate to our daily lives that reality itself now shapes and controls these purely digital experiences. Perlman spoke about big data, biometrics, and machine learning. In one performance project she referenced, sound and videos were controlled by the performer’s brainwaves, which acted as another form of surveillance, asking, "Is there a place in human consciousness where surveillance cannot go?" In contrast, Salter asked, "Immersion, what for?" He argued that most technologies project their own social and political ideologies onto their users. The human sensorium has always been a mediated one. Our sense of time is elastic; we are constantly being uprooted, and constantly transformed, stuck in an infinite regress from reality. The rift between Salter and Perlman’s stances was evident in how subjective alternate realities can be for each individual’s experience, making their description next to impossible to generalize or quantify for a mass audience.

Day three of the conference moved away from VR experience and and instead examined natural interfaces and technologies, such as augmented reality (AR) including games like Pokémon Go that have made AR a more mainstream phenomenon. Kristen Bergaust’s talk focused on her Oslofjord Ecologies, in which the relationship between the environment, sociology, and human subjectivity creates a more holistic definition of ecology. We need new social and aesthetic practices of the self in relation to the other in order to discover where new technological practices could lead.

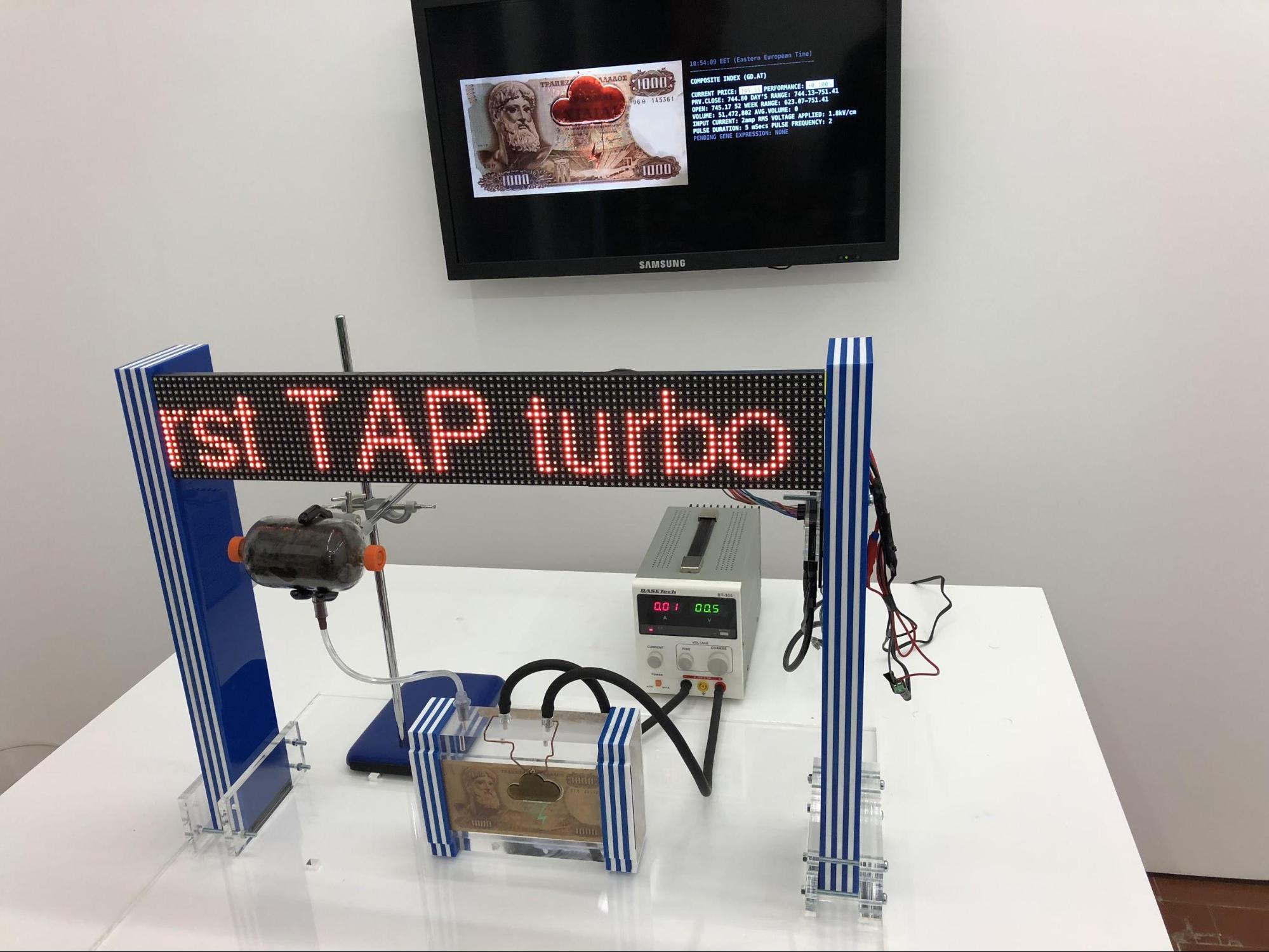

Raphael Kim presented Reviving Drachma, a bio-digital form of gamification in which Kim harvested bacteria living on the top of the obsolete currency of Greece, the Drachma, then converted current stock prices to electrical impulses stimulating the bacteria, which reflected the current economic state based through their activity.

Also interested in the defranchization of humans from a technology driven future, PhD student Carlotta Aoun directed the audience to consider the evolution of humanity where Web 2.0 could mutate into a hive mind or collective reality. Even as algorithms replace humans, humans are replacing algorithms, too. As we evolve, we will reach either a breaking point in this tenuous relationship, or reach equilibrium. The thought might have provided some comfort to attendees.

Reviving Drachma, Raphael Kim, 2017

The exhibition portion of the conference held at the Contemporary Art Centre in Riga, curated by Raitis Smits, featured a wide array of projects that focused mainly on VR and its relationship to physical spaces and the human body. Brooklyn-based artist Brenna Murphy exhibited her LatticeDomain_Visualize piece, a meditation labyrinth featuring a VR landscape of abstract shapes that one could move through with a corresponding physical floor that mimicked the virtual environment. The aesthetically complex VR piece HanaHana by French artist Mélodie Mousset asked the audience what would happen if "Minecraft & Tilt brush met in a Salvador Dalí painting." The project is a psychogeographic expression of women’s experienes of disembodiment and dissociation; it consisted of an artificial environment within which a floating hand simultaneously reaches for the user but also moves away from them on a parallel plane.

HanaHana Teaser, Melodie Mousset, 2017

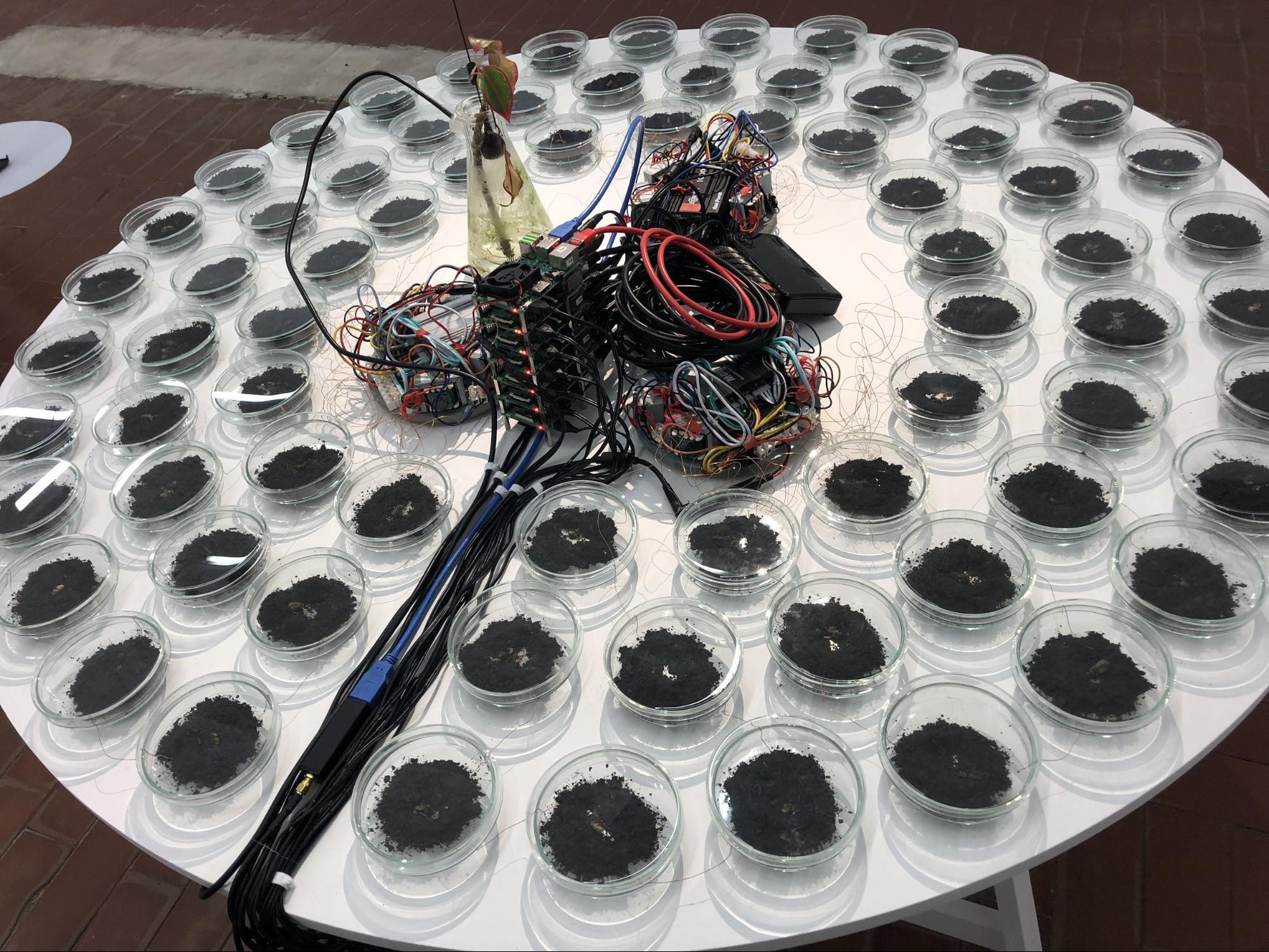

Exhibited projects in physical space included wr_t_ng m_ch_n_ by Austrian artist Hanns Holger Rutz. The piece is a writing machine, made from a circular tableau of petri dishes, containing small amounts of dirt piled on top of piezoelectric transducers. The project enlists the help of an algorithm, designed by the artist, that performs a continuous symphony of sound fragments. The fragments are rewritten based on specific movements of a similarity search in a real-time sound database. Also employing sound was Mind Message by Gunta Dombrovska from Latvia; it attached a Neurosky MindWave brainwave sensor to a simple player piano-like instrument, on which the user could create sound by flexing their literal mental capacities. The higher the incoming beta signal from the brain, the higher the tone played on the machine. While this type of interaction was immediate and satisfying, it did little to critically question the output of the MindWave, or suggest why such a device could be beneficial as an input stream.

wr_t_ng m_ch_n_, Hanns Holger Rutz, 2017

As the conference ended, there was a general sense that all of the media that we encounter daily could exist in virtual spaces, and that connections between physical and connected worlds have only become stronger and more interactive. As we continually reinvent interactivity, the term post- is eagerly used to suggest new waves of displacement through experience and media. This term might be a fallacy, as Finland-based artist and conference speaker Hanna Haaslahti eloquently asked, "Why is everything ‘post-’? This should be turned around into something new."

Both utopian and dystopian visions of virtual reality will eventually become rooted in the real world through artificial reality and other forms of engagement, so much so that there will be little distinction between the real, non-fiction simulations, and fictitious exploration. Luckily, there are events like Open Fields help us explore these emerging abstract territories, and lead us towards a more imaginative understanding of the future.

References:

- Kate Crawford "Artificial Intelligence’s White Guy Problem," The New York Times, June 25, 2016, found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/opinion/sunday/artificial-intelligences-white-guy-problem.html

- Open Fields 2017 Conference Website: http://festival2017.rixc.org