This essay accompanies the presentation of Lynn Hershman Leeson's Dollie Clone Series as a part of the online exhibition Net Art Anthology.

Soon after we can see, we are aware that we can also be seen. The eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world.1

CybeRoberta is a custom-made doll with a thick swath of blond hair, a red leisure outfit, and aviator sunglasses who comes replete with a standing mirror. She is also a telerobot whose eyes are webcams connected to the internet. With head-rotating capabilities that mimic a panoptic gaze, the doll records her immediate surroundings, made accessible online.

Art historian Amelia Jones describes viewing (and being viewed by) Lynn Hershman Leeson’s telerobot both in person and online, impressing the eeriness of being recorded:

“Even more unsettling, I discover a few days later that I was not only being observed but also simultaneously webcast live on LH’s website via the gaze of CybeRoberta (the footage from her camera eyes is available archivally and as live feed via webcam). I have been in more than one place at a time, and the past telescopes into the present as I watch myself being watched.”2

The doll, and its sister predecessor Tillie the Telerobotic Doll (1995), both part of the Dollie Clone series (1995-1998), fragment the viewer into multiple, uncontrollable, reverberating subjects. Rejecting the trope of doll as girlish plaything, here, she becomes a site for surveillance, voyeurism, and tracking. Despite her human—and docile—appearance, this doll destabilizes gendered archetypes, objectifying her viewer even as she is herself an object. At once a symbol of femininity and feminism, she is human and machine-like, a prosthetic, cyborgian articulation of fantasy and power.

Since the 1960s, Lynn Hershman Leeson has deconstructed the politics of subjectivity, most notably in relation to gender. She surveys—or surveils—the construction of the self in technological society through a body of work that spans over forty years. Her technologically and conceptually prescient photography, film, video, performance, sculpture, sound, and internet-based works inculcate the body, be it her own, that of her constructed avatars, or that of her viewer, in order to expand, trouble, and manipulate the boundaries of the self.3 For Hershman Leeson, identity is fractured and shifting.

The slippage between art and life is exemplified by Hershman Leeson’s long-term performative work, Roberta Breitmore (1974-78), a “simulated persona” which also takes the form of surveillance photographs, archival artifacts, and drawings relating to the character’s construction. For this piece, Hershman Leeson (and later hired actors) assumed a fictional identity named Roberta Breitmore, whose fiction was juxtaposed by her real activity in the world. The fabricated character rented an apartment, saw a psychiatrist, opened a bank account, attended Weight Watchers meetings, and went on dates she found by placing ads in San Francisco newspapers. Though many of Hershman Leeson’s female protagonists are made in her own image, Roberta, in contrast, wore a blond wig and heavy makeup, banal signifiers of Western media’s beauty ideals. Lynn as Roberta collapsed the space between the real and the performed, where transformation and representation became one and the same. Hershman Leeson has written, “Roberta was at once artificial and real. A non-person, the gene of the anti-body… As she became part of their reality, they became part of her fiction.”4 Hiding behind a guise, the artist peered into her own surroundings, becoming a voyeur critically observing the geography, history, and politics of her context. The act of looking became an act of control, which Hershman Leeson meticulously mapped and documented in this performance.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, CybeRoberta, 1995-1998.

CybeRoberta the doll is Roberta Breitmore reincarnate, a digitized clone that replaces the body of the character acting as Roberta, be it Hershman Leeson herself or one of her designated actors. The doll interacts with society not by going on dates or walking in the neighborhood, but by viewing and collecting data. Programmed to gaze upon the gallery viewers or website visitors, that is, to surveil, CybeRoberta and Tillie track a wide multiplicity of identities and viewers. Though CybeRoberta appears as a doll, or a simulated body, her main function is as a machine, and, more specifically, as a camera that files, records, and stores data. Yet by placing the machine in a human (or humanoid) form, Hershman Leeson presents her surveillance piece as a commonplace object. The doll is, after all, a familiar representation of the human, but more often, female, form.

In her 2014 text Girlhood and the Plastic Image, Heather Warren-Crow discusses the unstable, changing nature of girlish identity both online and IRL, calling the doll an icon of mutability and potentiality.5 The writer recalls Lewis Carroll’s Alice, herself both a real girl and a fiction imagined for the popular media of her day. While Tillie the Telerobotic Doll resembles Hershman Leeson herself and CybeRoberta represents Roberta (the artist in wig and makeup), culturally, the doll is often imagined to resemble a young girl, a reflection, or a mirroring of its owner who is tasked with animating it. Hershman Leeson’s telerobotic dolls, however, invert that model, toying with their viewers. By viewing the doll, or simply walking past her in a gallery space, she captures and circulates our image. As our images float around online, we end up, as Hito Steyerl has theorized, “represented to pieces.”6

In the 1990s, home use of the internet ushered in an era of accelerated communication and expanded informational resources. These advents mark a revolutionary moment of increased visibility and efficiency in late-capitalist society. In the ten-year period from 1993 to 2003, the percentage of the American population using the internet skyrocketed from 3% to 67%.7 Public interest in the webcam grew throughout the decade as well. Popular users garnered millions of views, such as Jennifer Ringley, a teenage girl who began to project her dorm room on Jennicam in 1996.8 Amy Shields Dobson examines the cultural significance of the cam girl, usually aged 13-25, who exposes the typically private, domestic space of her bedroom in the public arena of the internet. Most significantly, the cam girl acts as both director and actor, eschewing a passive, feminized space film theorist Laura Mulvey has termed “to-be-looked-at-ness.”9 Dobson continues, “Cam girls have appropriated the technology and the marketing methods of the patriarchal capitalist system to feed their own desires.”10 The cam girl desires visibility, casting the gaze onto herself, be it as a mode of work (on pay-per-view pornographic sites) or as a mode of social interaction.

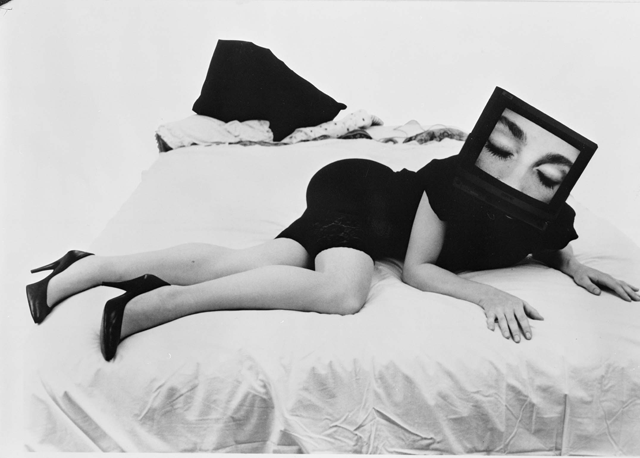

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Phantom Limb, 1988.

Hershman Leeson uses the webcam to complicate the feminist concept of the gaze, which rests on a binary between active and passive, viewer and viewed, by collapsing the binary between human and technology. The artist’s Phantom Limb photography series (1985-1988) responds, almost too literally, to these quandaries, wherein a slender white female body poses seductively, her head or full torso replaced by cameras and television screens. Where the body ends, the paraphernalia of media and image-production begins.

Instead of simply turning the camera and the gaze back onto the viewer, CybeRoberta and Tillie distribute the act of viewing across the apparatus of the network. The internet user, in turn, can manipulate the gaze of the doll, seeing beyond her own body, peering around the gallery at the dolls’ physical audiences who often appear on screen in parts. The machine, in this instance, is a body. Conflating these layers, we are rendered cyborgs.

Notes:

1. John Berger. Ways of Seeing. (New York: Penguin Books, 1972), 9.

2. Amelia Jones. "This Life" in Frieze. (London: Sept. 9 2008).

3. Howard N. Fox. “Introduction: Breaking the Code” in The Art and Films of Lynn Hershman Leeson Secret Agents, Private I, ed. Meredith Tromble. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 10.

4. Lynn Hershman Leeson. “Romancing the Anti-Body: Lust and Longing in (Cyber)space.” Clicking In: Hot Links to a Digital Culture. ed. Lynn Hershman Leeson. (Seattle: Bay Press, 1996).

5. Heather Warren-Crow. Girlhood and the Plastic Image. (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2014), 160.

6. Steyerl, Hito (2012). e-flux Journal: The Wretched of the Screen. ed. Juliet Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood and Franco “Bifo” Berandi. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

7. Robert J. Klotz. The Politics of Internet Communication. (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004), 18.

8. Barry Smith. Jennicam, or the Telematic Theatre of a Real Life, International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, (2005) 1:2, 92.

9. Laura Mulvey. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. (New York: Oxford UP, 1999), 809.

10. Amy Shields Dobson. Femininities as Commodities: Cam Girl Culture Amy Dobson in Next Wave Cultures: Feminism, Subcultures, Activism ed. Anita Harris. (New York and London: Routledge: 2008), 148.

Works cited:

Berger, John (1972). Ways of Seeing. New York: Penguin Books, 1972.

Dobson, Amy Shields (2008). “Femininities as Commodities: Cam Girl Culture.” Next Wave Cultures: Feminism, Subcultures, Activism. ed. Anita Harris. New York and London: Routledge.

Fox, Howard N. (2005). “Introduction: Breaking the Code.” The Art and Films of Lynn Hershman Leeson Secret Agents, Private I. ed. Meredith Tromble. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hershman Leeson, Lynn (1996). “Romancing the Anti-Body: Lust and Longing in (Cyber)space.” Clicking In: Hot Links to a Digital Culture. ed. Lynn Hershman Leeson. Seattle: Bay Press.

Jones, Amelia (2008). “This Life” in Frieze. London: September 9 2008.

Klotz, Robert J. (2004). The Politics of Internet Communication. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Mulvey, Laura (1975). “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP, 1999.

Smith, Barry (2005). “Jennicam, or the Telematic Theatre of a Real Life” in International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, Vol. 1, No, 2.

Steyerl, Hito (2012). e-flux Journal: The Wretched of the Screen. ed. Juliet Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood and Franco “Bifo” Berandi. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Warren-Crow, Heather (2014). Girlhood and the Plastic Image. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press.

Header image: Tillie the Telerobotic Doll.