The Airless Dyad

Saint Augustine asks of God in his Confessions, “Where do I call You to come to, since I am in You? Or where else are You that You can come to me?” The same matryoshka riddle describes the emulsified relationship between a pregnant woman and her fetus. How to address what is both inside and outside, of the flesh and separate from it? Time is no help to Augustine, but in pregnancy, the passing months eventually solve the conundrum. At some point the mixture of mother and child settles and separates; the creature that began as a microscopic cluster of cells begins acting like a cat in a kennel. By nine months gestation, the unborn parasite is so cumbersome that it displaces the mother’s lungs and bowels, strains against her skin with violence enough that cracks appear, and bruises internal organs that have never signaled pain before. These rough-and-tumble movements begin innocuously, in the fourth or fifth month, as gently as the popping of a soap bubble, as quietly as bouncing popcorn. Traditionally called “the quickening,” perceptible movement was the signal that the fetus had come into its unalienable otherness. In the early years of the American Republic, until the 1860s, abortion was widely practiced and (for the most part) legal until the moment of the quickening. Only the woman could announce when that was.

Prosthetic Voice

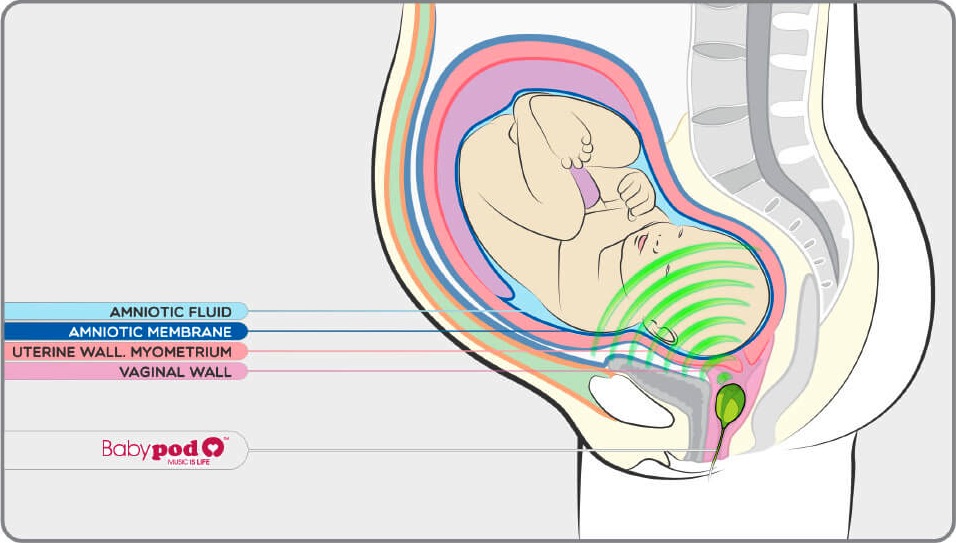

A company in Spain recently released a new product, the Babypod. The device entails a small roundish speaker, about 2 inches in diameter, equipped with a long cord attached to an auxiliary jack. The speaker is bubblegum pink, as is the carrying case, and made of a plastic that is soft and smooth to the touch. The idea is to insert the speaker inside one’s vagina, like a tampon, and connect the auxiliary jack to an iPhone, from which the mother-DJ selects a playlist. The music is piped in directly where it can be heard best, so the company promises, through the vaginal and uterine walls. When the product arrived at my apartment I was seven months pregnant. I tested it in the palm of my hand, concerned about the volume—prison torture has often included music—but even at full blast the speaker was rather quiet. In fact, once I pushed it inside my vagina, I heard nothing at all. I could only see that my phone was playing music and that I had an electric cord dangling from my crotch. I played random bits of indie music and with no specific intention an album of Shaker spirituals. I called my older daughter over to choose a song, and she selected “It’s a Hard Knock Life,” from the soundtrack to Annie, and Beyonce’s “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It).” The fetus occasionally squirmed during our playlist but not more than usual. It evidenced no preference for any specific song or style of music, and it failed to register the end of our set. (I tugged the cord; the speaker flopped out.)

Abdominal speakers, attached to the pregnant belly with suction or tape, are popular in the US, and endorsed by major pediatric hospitals. They are touted as a bonding device, but also as a way to stimulate fetal brain development. (It is always assumed that mothers-to-be will play culturally aspirational music: Beethoven, not Billy Joel.) The Babypod claims to be superior to these older methods of fetal acoustic stimulation; a diagram in the manual shows that an intravaginal speaker sits much closer to the fetal ear than a speaker attached to the outside of a pregnant belly. By nestling in the vagina, the Babypod jumps the boundary between inside and outside. Presumably it’s the difference between overhearing your neighbor’s music, and suffering your roommate’s.

Women have presumably always enjoyed the utility of an interior pocket, though no one has written this history. The 19th-century spirit medium Eva C. had a trick of producing ectoplasm from her vagina, and police report finding jewels and drugs, money and handguns, stolen phones and credit cards. In these cases, the vagina is treated as a secret lock box—a hiding place no one will think to look, the corporeal equivalent of a buried treasure chest. The Babypod inhabits the woman in a totally different fashion. The very purpose of the device is to announce itself and broadcast sound. It makes the vagina speak. The Vagina Monologues didn’t need to get more literal, but they have.

Vagina Language

The French symbolist Marcel Schwob published a short story in 1891, “A Talking Machine,” about an apparatus he describes as being very much like a talking vagina. In the story, a loquacious inventor who appears to be insane leads the narrator to the outskirts of the city, to a hidden cavern where his machine belches and groans. The gargantuan automaton is all mouth and gullet; it takes up an entire room and reaches the ceiling. The narrator is repulsed by this monstrosity and the reader is expected to feel the same. In Schwob’s description, the talking machine is only a thin variation on the vagina dentate—a vagina equipped with castrating teeth—that populates myths and horror films. Schwob luxuriates in the words and phrases of the feminine grotesque: “blotched and swollen;” “bulging” and “shuddering;” “fleshy” and “gigantic.” The lips itself he describes as a “black and swollen labial fold.”

The talking vagina may be invented by a man, but it is operated by a woman, a thin silent woman who slumps anxiously at the control panel. Eager to impress his visitor, the inventor commands the woman to make the machine say, “I have created the word.” The machine has never managed such a phrase before. Struggling and stuttering, the labial lips stammer only “Wor-d, Wor-d, Wor-d,” and then the machine self-destructs. The woman operator disappears in a pile of flesh-like matter and the story ends. The moral of the story: Schwob’s vagina can talk, but it cannot utter the words “I create.”

The Volume of Motherhood

With my first child, who cried incessantly, I had the sense that the quality of my mothering was proportionate to the extent to which I relinquished all vanity, relinquished even the basic self-possession that keeps a person tethered to the world. The needs of the child seemed to demand my personal dissolution. I became nothing but a breast and a means of motion. The first months of motherhood felt like a prolonged process of self-elimination, a suicide dosed in dribbles. I kept dialing back the volume of my own voice, again and again, wondering how long this would last, and if my mute would become permanent.

Friedrich A. Kittler writes in his history of the typewriter that typewriters became popular only at the moment a woman was suggested as typist. The utility of the machine clicked, suddenly, when an advertisement posited a female operator. The convenience of male thought instantly rendered as mechanized ink on paper became intelligible only with the intermediary of a female body. Sitting as alert and upright as an antenna, such women were “type-writers” at the typewriter, linguistically indistinguishable from the tool they used. “The relation between organism and machine has been a border war,” wrote Donna Haraway in 1985. But the typewriter’s feminine casting was not a war about where to place the border, or a war about who crosses the border, or a war at the border. It was not even a war. It was an unthinking assumption that there was no border—no structural barrier of significance between female operator, eponymous machine, and male voice.

In my case, things improved when I thought not of maternal love or its absence, but of work—the kind of work on which survival depends, which is not the place to voice one’s own boredom or fatigue or brilliance. “Don’t write, translate,” Stendhal advised women, “and you will earn an honorable living.” I came to understand my task as not only narrow in scope—to hear and respond immediately, efficaciously, indefatigably—but compelled by circumstances over which I had no control. My job was only to listen and type.

The Fetal Ear

The research of ear, nose, and throat doctor Alfred Tomatis in the mid-twentieth century found that a fetus’ inner ear is completely formed by the fourth month of the pregnancy, such that the creature develops not only in a singular landscape, but in a singular soundscape. Tomatis even suggested that the mother’s skeleton is specifically designed to support this soundscape—her pelvic bones conduct sound better than other bones. “Humans emerge without exception from a vocal matriarchy,” writes historian Peter Sloterdijk in his account of Tomatis’s research.

Tomatis did not, however, characterize the fetal acoustic bubble as a pleasant or calming place. The mother’s blood whooshes, the heartbeat thunders, her digestive tract churns. Sloterdijk speculates that the fetal experience is akin to “living in a 24-hour construction zone.” The leaf blowers and car alarms of the exterior world are layered on top of an already high-decibel interior thrum. Perhaps this is why so many parents report babies calming with the sound of a vacuum cleaner, or a hair dryer.

Through this cacophony, Tomatis believed, the fetus is always straining for one sound in particular: that of the mother’s voice. It is her pitch and cadence that give the infant joy, her intonations that form the emotional substratum of the creature’s first love. (Tomatis earned public notoriety—and disapproval from the medical community—by designing a therapeutic treatment for singers that included playing recordings of the clients’ mother’s voice. Sting, Gérard Depardieu, Maria Callas, and others swore by it.)

If Tomatis is correct and the fetus truly desires to hear my voice, then it stands to reason that the ideal use of the Babypod is to play myself—to redirect my larynx inward and pipe recordings of myself inside myself. I consider this, consider recording my own conversational blab or even addressing the unborn babe directly. In the end, I decide that I prefer the scenario in which a half-formed person has focused all of her instinctive vim on straining to hear my voice, just mine. Pregnancy is uncomfortable, and this seems a vanity to which I am entitled.

The Ear that Hears Too Much

In Thus Spake Zarathustra, Nietzsche furnishes an image that became key to understanding my own new-mother miasma. Nietzsche is describing bodies that lack proportion, bodies that are overburdened by some features and missing others: “men who are nothing more than a big eye, or a big mouth, or a big belly, or something else big.” As an example, Nietzsche reports seeing a giant ear, “an ear as big as a man!” Peering closely, he realizes the ear in fact has a man attached to it, albeit a tiny man who wobbles beneath the weight of his immense hearing organ. The man’s soul hangs from his body like a deflated balloon.

The people tell Zarathustra that this man is a genius, but Zarathustra disagrees. He is not a great man at all, writes Nietzsche, but a “reversed cripple.” He means that the man with the giant ear suffers his disproportion. He is only a listener, not a speaker; his anima withers beneath the enormity of his ear. I relished this passage, happily cutting it loose of Nietzsche’s context. The giant ear might be misunderstood as genius, but also as glorious martyrdom, or valiant self-abnegation, or—as I interpreted it—selfless mothering. Zarathustra alone seemed to understand my predicament. Exaggerating the propensities of the ear requires minimizing other propensities; listening demands the cessation of speech.

Nietszche’s cripple-with-the-giant-ear finds his kin in the protagonist of sci-fi writer Octavia E. Butler’s Parable books, Lauren Olamina. Lauren suffers from what Butler terms “hyperempathy syndrome.” The symptoms are such that Lauren acutely feels the emotional and physical sensations of others. She can be disabled by the killing of a dog, or wildly distracted by lovemaking in an adjacent bedroom. As in Thus Spake Zarathustra, Lauren’s disease is a problem of proportion: her ear is too large, her sensitivity impractically acute. The trait of empathy, long imagined as the special province of females, exists on a spectrum that links masochism with generosity. Lauren occupies the extreme end, literally bleeding when others bleed. She is disabled by sensations against which she has no bulwark, no levee. Lauren hides her disease, and describes herself as “damaged.”

Maternal Holding

When my due date arrived and the creature hadn’t indicated any interest in birth, I got out the Babypod again. But I had no idea what to play. I was scrolling through my phone when I remembered a story about a man who uses music to communicate with animals. He was asked to join a rescue crew in Alaska in an attempt to save three gray whales trapped in an ice flow. The rescuers had created a channel wide enough for the whales to swim to open sea, but they wouldn’t budge, and the animal communicator was asked to coax them out. It was suggested that he use his underwater speakers to play recordings of predatory killer whales. The man demurred, selecting instead Graceland by Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. In fact, the song worked; two of the three whales escaped the ice hole and found the sea.

I remembered the story so well because it had seemed unfathomable that Graceland could affect the prerogative of a whale. Now I recoiled at the obvious analogies, between dropping speakers in icy northern waters and pushing speakers into interior depths, between the recalcitrant whales and my recalcitrant fetus, between assuming I could know the mind of my unborn creature any better than I could know the mind of a whale. I put the Babypod away. I’d been slow to recognize the demand of this situation: nothing more and nothing less than arduous passivity.

Tuning Out

As soon as Tomatis posited the scenario of a tiny fetal ear pitched against a raucous hubbub, he was forced to a startling conclusion. The fetus must learn, at a very early stage of development—before its eyes have pigment, before its pancreas or lungs take shape; the same age, incidentally, at which a mother might feel the quickening—how to filter its audio input. It must learn to relegate some sounds to the background and move others to the foreground, to mute the fire alarms and digestive rumbles so as to spotlight the mother’s melodious lilt. The delicate modulations between tuning out and tuning in, between an ear that is neither too large nor too small, are among the earliest manifestations of human subjectivity. A fetus becomes a person by learning when to listen and when to stop.

Special thanks to Courtney Stephens and Gabriel Larson.