RAUM 115, a small seminar space on the first floor of the Universität der Kunste (UdK), Berlin, is mostly used to show student films and presentations. Two wooden desks are placed to the right of the room in front of a large blank wall, with sofas, chairs, and a 3D projector facing opposite.

In this nondescript classroom, every month or so an eclectic crowd gather for discussions hosted by the Research Centre for Proxy Politics (RCPP), a long-running program organized by Boaz Levin, Vera Tollmann, and Maximilian Schmoetzer in association with Hito Steyerl and her class at UdK. RCPP’s workshops and lectures usually run for several hours, shifting with ease from tech tutorials, aesthetic philosophy, and political activism to Neolithic anthropology, e-waste, and astrology.

The program has been running since January 2015, and I have attended all but a few of the meetings. Guests have so far have included artists, writers, academics, activists, and technicians (often overlapping at least two) such as Zach Blas, Louis Henderson, Tiziana Terranova, Paul Feigelfeld, Manuela Winbeck, Charles Stankievech, and Wendy Chun. Slated for 2016 are Oleksiy Radynski, Francis Hunger, Philipp Borgers, Harry Sanderson, Ben Vickers, and Brian Holmes. Most meetings revolve around four recurring questions: How could resistance be created in the context of network technologies like data and algorithms? Could such processes be hacked? What technical processes must be understood in order to produce political action? What is the role of art in times of emergency?

January 2015

The first workshop is filled mostly with Steyerl’s students, or the tourist equivalent thereof, in Berlin to attend Transmediale and CTM. It is led by artist and writer Zach Blas who starts by discussing his text “Contra-Internet Aesthetics” (inspired by Paul B. Preciado's Contrasexual Manifesto). It is appropriate for Blas to begin the program, as the essay ends with a series of bullet points summarizing a polemic often referred to:

- An implicit critique of the internet as a neoliberal agent and conduit for labour exploitation, financial violence, and precarity.

- An intersectional analysis that highlights the internet’s intimate connections to the propagation of ableism, classism, homophobia, sexism, racism, and transphobia.

- A refusal of the brute quantification and standardization that digital technologies enforce as an interpretative lens for evaluating and understanding life.

- A radicalization of technics, which is at once the acknowledgement of the impossibility of a totalized technical objectivity and also the generation of different logics and possibilities for technological functionality.

- A transformation of network-centric subjectivity beyond and against the internet as a rapidly developing zone of work-leisure indistinction, social media monoculture, and the addiction to staying connected.

- Constituting alternatives to the internet, which is nothing short of utopian.[1]

What generates the most discussion, however, is Blas’s project Facial Weaponization Suite, a workshop that aims to develop forms of collective and artistic protest against facial recognition technologies. Blas explains that the masks create anonymity by confusing visual patterns, the kind a camera uses when travelling through airport terminals, for example. Questions focus on the warped, often colorful, shapes that are produced, and what functional value they actually hold as a protest (or opposition) to surveillance, or in other words, their utility.

This approach of artistic research continued with a screening and Q&A from filmmaker Louis Henderson, showing his work All that is solid (2014), a documentary essay that links e-recycling and neocolonialism in the waste ground of Accra and illegal gold mines in other parts of Ghana. The film cuts between screenshots of Google searches, ethnographic footage reminiscent of Jean Rouch, and 3D renderings of the mines to link together the globalized production of digital equipment and its material resource (along with the waste and mass exploitation involved).

An excerpt from the film’s synopsis outlines this attempt at proximity concisely:

This is a film that takes place. In between a hard place, a hard drive, and an imaginary, a soft space – the cloud that holds my data. And in the soft grey matter, Contained within the head.

A possible link between Blas and Henderson is their attempt to describe specific technological processes—or in Blas’s case, how these could be imaginatively countered—contextualizing their effects within broader contexts and histories, such as colonialism and surveillance. While the works enable a framework through which to understand the implications of new technical processes, representations of data and networks via CGI (or screen recordings) avoids exploring in detail the visual representation or link, of an algorithm to its effect on political agency.

Unfortunately, this often breaks down the precise and comparative scope of the project (in contrast to later meetings), and offers a limited discussion of problems that arise from efforts to represent algorithmic logic: data, networks, and the power structures that govern them, a task that artists seem well-equipped to tackle.

There is a question from Hito Steyerl, it isn’t fully answered here or anywhere else, but seems important to remember: As an artist, does Henderson find it increasingly necessary to provide answers to overt political questions while discussing his own work during screenings and artist talks (or perhaps the reverse, does he find himself trying to provide one)?

Screenshot of video by Sheryl Gilbert, YouTube.

February 2015

A month later in February, the theorist/activist Tiziana Terranova presented her current research into “social” networks and Foucault, with an essay aptly titled “Securing the Social.” The workshop began with the infamous quote from Margaret Thatcher, “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women.”

Discussing the topos of networks and data visualizations, alongside outlining her essay, Terranova impressively argued that neoliberalism has found in social media the techniques of which the “social” can finally be known (something it has denied for so long), or in other words:

“Sentiment analysis” and various types of “social analytics” […] make networks, relationships, communities and patterns visible, working with the logic of individual expression. These techniques can operate in real-time, revealing constant fluctuations in social activity, just as prices reveal constant fluctuations in economic activity.[2]

I am reminded of another Thatcher quote in response, though a less known one: “Economics are the method, but the object is to change the heart and soul.”

Terranova concluded her workshop by introducing the Robin Hood Minor Asset Management Group, a cooperative that works as a form of financial investment similar to a hedge fund—analyzing big data, writing algorithms, deploying web-based technologies, and engineering financial instruments to create and distribute profit to members (their tagline is “hacking finance”).

The cooperative is registered in Finland, and operates under EU regulations and Finnish law—it has a board of directors (which Terranova is on) that monitors operations and members sign up by purchasing a single share (more can be bought). Along with profit being distributed to members, a portion is invested in projects via an open call once a year. I go into detail because it seems important to note this structure: similar to hedge funds in its organization, yet somewhat symbolic (like a provocation). What is interesting with this type of activism (if it can be called that) is its redefinition of the term. Their website reads, “Robin Hood is another way to Occupy Wall Street,” but unlike the “local” action of Occupy, it begins to confront the abstract forces of capital that make such action impotent (or at least partially so).

Compared with others in the program, the intention of working within areas like the financial sector rearranges the question of alternative or subversive action for both artists and activists: What would agitprop look like now with these new criteria? Is “making visible” structures of oppression or control still useful? What role does art have in both criticizing such structures, and building new ones?

At the end of Terranova’s talk, someone in the back of the room timidly asked, “So...what can we do now, how can we act, and what would action look like?” Though no model would be perfect, Terranova said, shrugging and looking back at her laptop jokingly, ideas must be tried and tested in practice if we are to find workable alternatives for the future.

November 2015

It isn’t until later in the year that I am able to get to another meeting, unfortunately missing Paul Feigelfeld (of the vital Refugee Phrasebook), Manuela Winbeck, Tatiana Bazzichelli, and Eben Chu. It’s November, and the afternoon is led by Charles Stankievech, a curator, writer, and artist who replies to every question with an enthusiastic “That’s a great question!”

Focusing on strategies to access military ecologies and infrastructure, the “visible invisible” or “security through obscurity,” as described it in the outline, Stankievech introduces “Counterintelligence,” an exhibition he curated in 2013, and “The Soniferous Æther of The Land Beyond The Land Beyond,” a series of photographs and videos produced during a residency as “War Artist” at the Canadian Forces Station Alert on Ellesmere Island, Nunavut.

Double agents and whistleblowing: the FBI exhibited alongside Donald Judd. Can this kind of work go beyond the symbolic territory of cultural production and into the political? Is this the desired effect?

Much like Blas and Henderson, Stankievech begins with the empirical—images or documents from a site, process, or object—and develops a framework to contextualize these in wider terms. The exhibition “Counterintelligence” in particular brought up a discussion about the use of narrative in making planetary scale military technology perceptible (or at least comprehensible), perhaps as a counter to the NSA’s so-called “Treasure Map.”

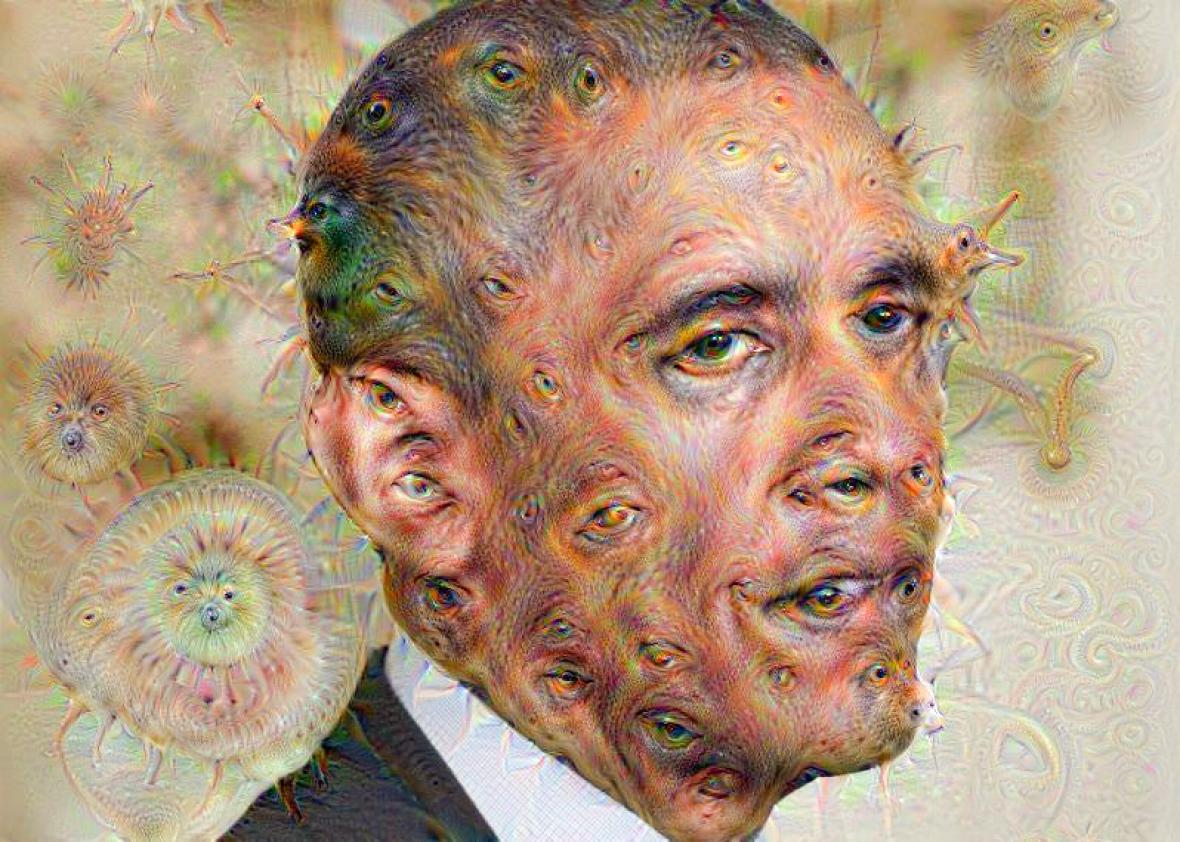

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker using Dreamscopeapp. Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

December 2015

The last lecture held in 2015, delivered by Wendy Chun and titled “New Media is Wonderfully Creepy,” took place in a much larger room at the back of the university. Trained in systems design, and with extensive experience in hardware research, Chun, explaining the title, said, “New media technologies provoke both anxiety and hope: anxiety over surveillance and hope for empowerment. These two reactions complement rather than oppose each other, by emphasizing how exposure is necessary in order for networks to function.”

Through specific examples, she elucidated the intersection of surveillance, control, and consumer tendencies in computing processes, and the material conditions within which these exist. One example was Amazon’s use of consumer data—the company-recommended books, DVDs, and other products based on highlighted sentences from Kindle users. As Chun puts it, “reading is writing for somebody else.” (This also accounts for surveillance systems that follow a similar logic.)

What Chun points to is that new technological infrastructures require a rethinking of individual and collective agency, as privacy is privatized, and individual deviation is swallowed by pattern recognition and predictive governmentality.

In a passage from her book Programming Vision, this analysis of soft/hardware and its concomitants such as naturalizing economic hierarchies or predicting consumer tendencies, expands on sentiments expressed earlier by Terranova:

In our so-called post-ideological society, software sustains and depoliticizes notions of ideology and ideology critique. People may deny ideology, but they don’t deny software—and they attribute to software, metaphorically, greater powers that have been attributed to ideology. Our interactions with software have disciplined us, created certain expectations about cause and effect, offered us pleasure and power—a way to navigate our neoliberal world—that we believe should be transferrable elsewhere. It has also fostered our belief in the world as neoliberal; as an economic game that follows certain rules.[3]

In the following sentence, Chun goes on to outline the important aesthetic problem involved in this analysis (possibly explaining the current interest shared by both artists and theorists) that could describe RCPP as a whole:

The notion of software has crept into our critical vocabulary in mostly uninterrogated ways. By interrogating software and the visual knowledge it perpetuates, we can move beyond the so-called crisis in indexicality toward understanding the new ways in which visual knowledge—seeing/visible reading as knowing—is being transformed and perpetuated, not simply rendered obsolete or displaced.

Postscript

Directly after Chun, Steyerl gave an impromptu presentation of a text she was working on at the time about big data and pattern recognition. Drawing a line of thought via Google algorithms, the George Michael song “Outside,” and Putin’s face appearing in a Starling cloud, the discussion landed on an appropriate topic.

Today, when mining includes data as well as coltan, and protests turn into holograms,[4] new knowledge and visual imagery must be produced to negotiate these landscapes. Yet, Steyerl continued, at present this resembles a kind of apophenia (a human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns within random information), a political act used to produce credit ratings and implicate citizens in illegal activities.

A visual analogy for this process is inceptionism, the resulting images of which can be found online, where creatures and shapes emerge from pixelated imagery.[5] These alien-like results are due to algorithms failing to recognize a variety of objects and signs, instead projecting a coherency onto the picture so it can be understood.

Paraphrasing György Lukács, Steyerl concludes, “The typical characters (or protagonists) of realism embody the objective social forces of their time. It is these images that embody the ‘objective’ technological force of ours. In this sense, they are a deeply realist representation.”

At the end of this last meeting, a question was asked that neatly tied together the academic nature of the conversations, the audience (mostly art students) and a possible outcome: “What are the tools we could use to produce images of algorithms, networks, and data—of both complex soft/hardware and the resulting hope and anxiety (as Wendy Chun puts it)—and how could we make or find them?”

Hito ironically responded, “Go outside!”

To go from there will require collaborative thinking and practice, from aesthetic analysis, legal and economic know-how, to coding and direct action alike. It means building a vocabulary that can be mobilized; a task that RCPP and their participants are working hard to produce.

Top Image: Screenshot of ALL THAT IS SOLID, 2014 by Louis Henderson.

[1] Omar Kholeif (ed.), You Are Here: Art After the Internet (Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications, 2014), 90.

[2] William Davies, quoted in Tiziana Terranova, “Securing the Social: Foucault and Social Networks,” see https://www.academia.edu/11258389/Securing_the_social_Foucault_and_Social_Networks

[3] Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed Vision (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 92.

[4] Boaz Levin and Vera Tollmann, “Plunge into Proxy Politics,” see: http://rcpp.lensbased.net/post/124148628115/plunge-into-proxy-politics

[5] See http://googleresearch.blogspot.co.uk/2015/06/inceptionism-going-deeper-into-neural.html