The latest in a series of interviews with artists who have a significant body of work that makes use of or responds to network culture and digital technologies.

Christine Sun Kim, Game of Skill 2.0 (2015)

Your own physical presence seems integral to your work. Sometimes you are literally in the space, guiding people and forging an interaction—I think of Gesture Sign Art that I saw at Kunstlerhaus Bethanien in 2012, where you showed instructions on an iPad for viewers to manipulate transducers and piano wires in space to create vibrations together. At other times you leave objects in the space that show evidence of your actions, like the Speaker Drawings that manifested transducer vibrations on paper. Do you think of those projects in terms of action and evidence? Are they autonomous, or do they require you to activate them?

Some of my performances are about the process of building a platform and conducting participants to become my voice (Subjective Loudness in Tokyo, 2013) rather than leaving my traces afterwards. It seems as if my "voice" as an artist cannot be conveyed without all those people’s involvement. It’s almost a direct reflection of my everyday communication. I expand my voice through other voices.

The Speaker Drawings were my baby steps as a sound artist, and I don't do them anymore. They were very straightforward: sound to visual. I'm so into the conceptual aspect of sound that these drawings almost feel like decoration, almost empty... or just a vessel. I like getting messy, though.

Christine Sun Kim, Speaker Drawing (2012)

I met you while working for the Bard MFA program and was hired to be your note taker—I would transcribe all your studio visits with professors and afterwards you would read how the conversation had been translated through your interpreter from ASL [American Sign Language] to spoken English. I suddenly understood to what extent all communication is mediated artificially, and also confronted issues of accessibility for the first time. Do you think you're placed in an "educative" role by default in an art world where accessibility is so rarely part of the conversation?

Oh yes. I often tell my friends that I am an educator by default. Sometimes I enjoy that, sometimes not. Most art museum websites have videos and audio files that everyday people can easily watch/listen to, but I could safely say that 95% of them aren't accessible to everyone. So my art knowledge sometimes stops right there (apart from internet-ing or dialogue). If it weren't for the museum job I had at the Whitney, giving tours for deaf audiences, I wouldn't have had access to amazing documents such as research packets on special exhibitions, transcripts of curators’ walkthrough tours, and exhibition catalogs. What blows my mind is that the art world is full of people claiming that they're open minded about "differences" or "challenges" and call themselves innovative. But when it comes to requesting minor adjustments such as adding captions, they bite my head off—there’s so much discomfort in that space. I know accessibility can be such an ugly word—even I try to avoid it. "Universal design?" That can really water down other people's work, and mine. There needs to be much more space for us to experiment and try new ideas for making art inclusive. That would also push art/ideas much further with new questions.

Christine Sun Kim, Face Opera II (2013)

Audiences are often struck when watching an ASL interpreter by how much sign-based communication depends on facial expression. You commented on that with Face Opera (2013), in which you and a group of deaf participants used only your faces (and some typed messages on an iPad) to build a soundless operatic narrative, cutting out the role of the interpreter altogether. Was this also a work about how much is lost in translation, about how much work sometimes goes into communication for you?

The audience’s interpretations of my work largely depend on their understanding of my relationship with my interpreters. If you think the process involves transliteration (direct translation without considering its context, similar to Google Translate), then there's not much of a realization. The bottom line is that I'll never get the full information through an interpreter, but I have my own way of assessing what happened. For instance, at Bard, during a studio visit with a teacher, I would try to put everything together inside my head by watching my interpreter signing, seeing how my questions are being answered, figuring out how much I trusted my interpreter's interpretation, observing how the teacher behaved, reading your notes, reviewing the meeting with the interpreter to maximize my understanding, and taking in external details (i.e. gossip, ha ha). If the whole meeting had been conducted in full ASL (deaf teacher, deaf student), it would have been very straightforward—maybe less subjective. There is a lot of trust involved in my communication, as I constantly work with new interpreters, organizers, faculty members, and administrators. Sometimes it feels like dating my own voice; it's like being on a first date every day.

It seems that whenever I present my work as a "sound" piece, the audience is most likely to open their minds and look into their own subjectivities. A friend of mine mentioned that sometimes when you're supposed to "listen" to my work, the experience itself becomes the space for you to re-think your subjectivity. But sometimes I think musicians or sound artists have the privilege of being misunderstood, or not understood. In my case, I have a fear of not being understood, which means I get trapped in your subjectivity, not the other way around.

Christine Sun Kim, Subjective Loudness (performance installation at Sound Live Tokyo, 2013. Photo: Masahide Ando)

You've been a TED fellow and a guest artist at MIT Media Lab, and done all sorts of collaborations with science and tech. Not that there needs to be any separation between aspects of your life and work, but is there any difference in the way your work evolves and is received in those contexts versus the art world, which is often pretty hermetic? What emerged from TED and MIT, and how has it fed into what you create for art institutions?

My work has always been in between disciplines and categories. For a long time, I wanted to stay inside the "art world" (maybe for the sake of belonging or earning respect), but it seems that my work resonates with many non-art communities. When I first was awarded a fellowship from TED, I wasn't sure what to make of it because I thought it was corporate and didn’t want to be associated with it… But I went for it. That was an eye-opener for me because TED has a massive, powerful platform full of resources and people who are totally into new ideas, and I felt they really listened to what I had to say. The experience itself helped me realize that the model of being an artist in the art world doesn't fly with me. I had to step out of that community and explore new models for my art. With MIT, it’s too early to tell what will come of it, since it just started this year. So far no specific projects have come from either fellowship, though they do offer leverage, opportunities, networks, friends, and resources. I feel more hyperconnected than ever and it's scaring me a little.

In your installation Game of Skill 2.0 for the "Greater New York" installation at MoMA PS1, the audience is invited to drive a radio along a cable line, changing the sound of the voice coming from the radio according to their walking speed and direction. It seems like this work is geared more towards a hearing audience; do you feel the need to make your art accessible for all, despite the fact that the hearing world is not made entirely accessible for you?

I remember a time at Bard when I did a total sound piece and I felt conflicted about my work not being 100% accessible (as you said, I am an educator by default) and my co-chair, Marina Rosenfeld, said "Are you making art for yourself, or them?" She was right to ask. I started focusing on what interests me, and when there are deaf people in the audience, I always make time to explain to them my process and what my hopes are. As long as they learn about the concept in ASL, they will have the same experience as hearing people, just on a different level. I did a video of myself explaining Game of Skill 2.0 at MoMA PS1 except that it has no spoken English or captions. Hearing participants listen with their ears and deaf participants with their eyes.

I am amazed at how much feedback I've received from the show at PS1. I was there on the opening day with two interpreters, and I noticed that people with sensitive hearing could hear the voice coming from the radio very clearly (my text is about the future of NYC) and that people with less sensitive hearing found her voice less clear. It shows that everyone hears at various levels, like different small amounts of deafness. But they all need to learn how to walk and hold up a device in a particular way to hear full sentences; they function like human turntable needles. It takes practice. Also, it was funny to watch people getting very self-conscious about their new "listening" skill. They were saying, "Am I doing it right? Stop looking at me!”

For my solo show at Carroll Fletcher this fall, I'll show both Game of Skill 1.0, an earlier version originally shown at White Space in Beijing, and new drawings. The older devices used in the first Game of Skill have external speakers and two batteries instead of one. Both versions were built by electronic instrument designer Levy Lorenzo. And at Sound Live Tokyo also this fall, I will host a concert-like event with curator Tomoyuki Arai's help. We've invited musicians to contribute audio files of 20 decibels and below. The sounds are below your average hearing range, and they're full of beats that will be mostly transmitted through materials such as the walls and floor. Let’s hope no ears will bleed.

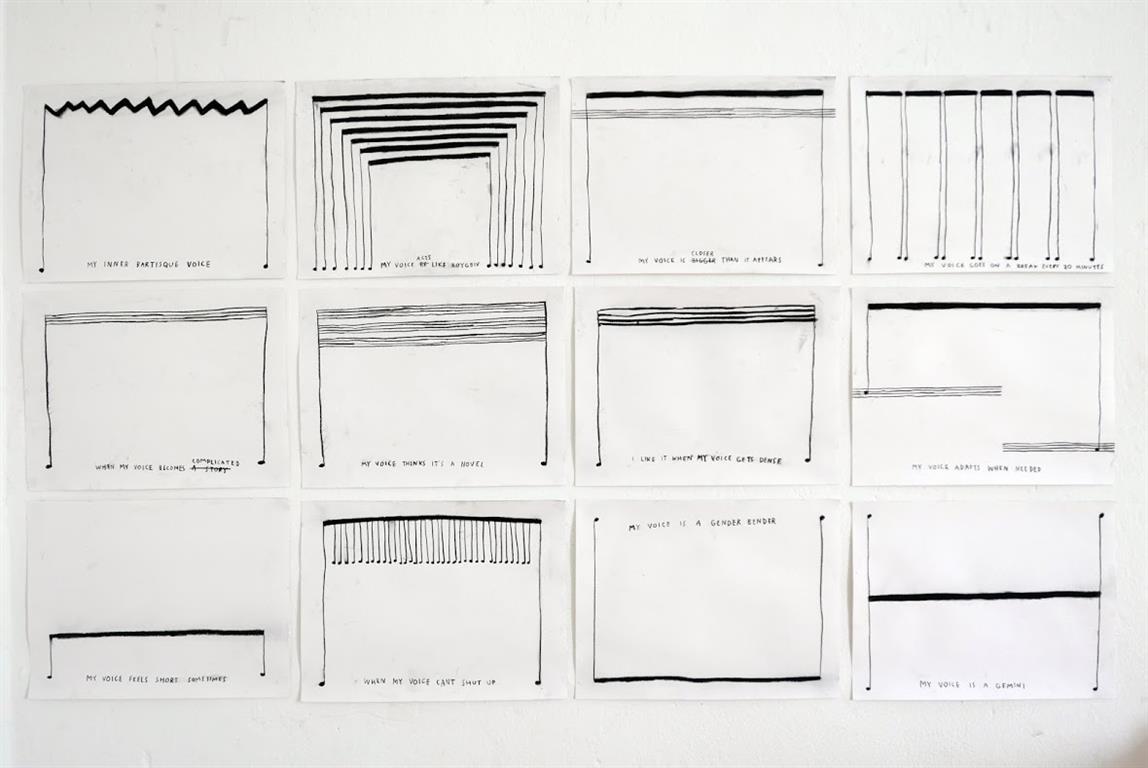

Christine Sun Kim, new drawings to be shown at Caroll Fletcher as part of the exhibition "Rustle Tustle"

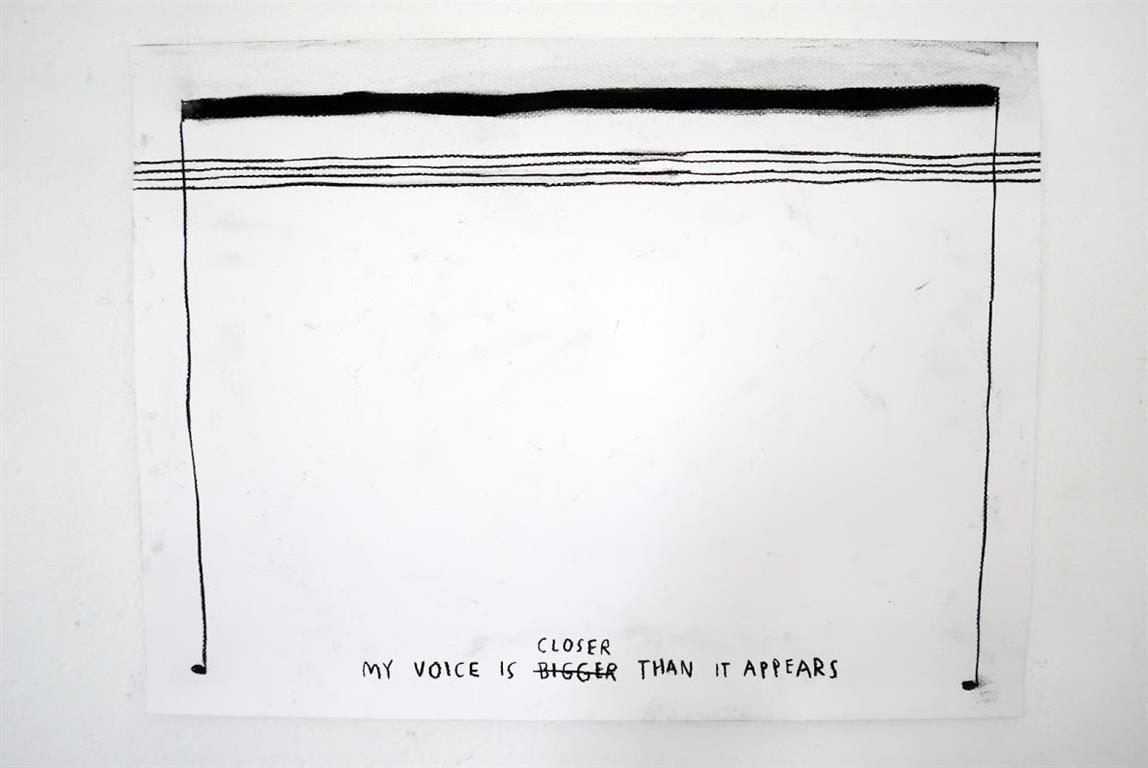

Christine Sun Kim, new drawing to be shown at Caroll Fletcher as part of the exhibition "Rustle Tustle"

Questionnaire:

Age: 35

Location: Berlin, Germany

How/when did you begin working creatively with technology?

I've had a TTY (deaf phone, very '80s and '90s) and internet almost all my life. But when I got my first iPhone in 2011, it really changed the way I interact with non-signers and I started to incorporate it into performances. I never work with an interpreter during performances, mainly because I prefer to have direct connection with audiences and remind them that I do not have a sonic identity.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

At Rochester Institute of Technology, a BS in Multi-Disciplinary Arts; an MFA in Studio Arts at the School of Visual Arts in New York and an MFA in Music/Sound at Bard College.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously?

I used to work as a digital archivist for W.W. Norton and Co., a publishing company, and as a freelance educator at the Whitney Museum.

What does your desktop or workspace look like? (Pics or screenshots please!)

Living room as temporary studio for three days before my next trip. I was never an artist with a permanent studio, but I hope that will change soon.

Desktop–I try to keep it clear, easier for me to navigate. I like studios and desktops that look almost empty because it helps me think clearly.